There's a common misconception that clothes made in the United States or Western Europe are "good" and clothes made in low-cost countries such as China are "bad." Let's talk about it. 🧵

https://twitter.com/TheFireman430/status/1847509570656358438

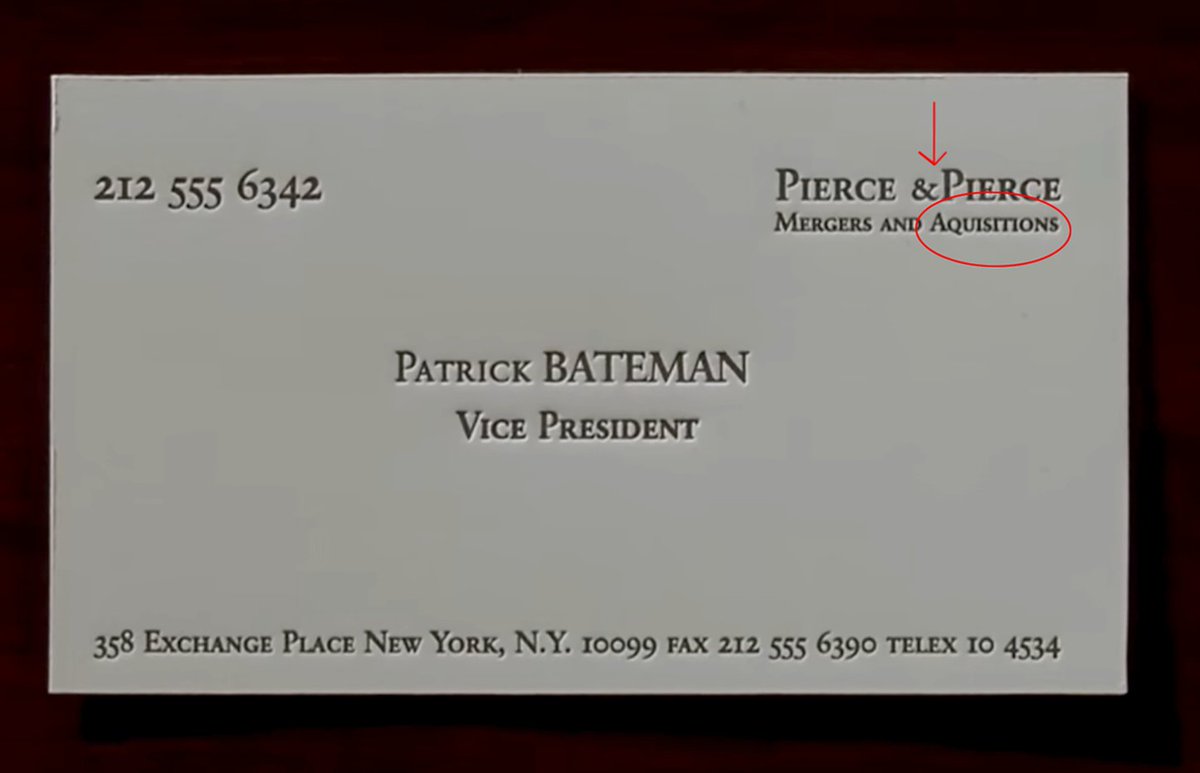

In 1965, Robert Schooler conducted an experiment. He gave 200 university students swatches of the same beige fabric—a plain weave made from a 80/20 mixture of cotton-linen. The swatches were identical except in one regard: the country of origin label.

One swatch was labeled "made in Mexico," another said "made in Guatemala," and the others bore names of other Latin American countries (e.g., Costa Rica, El Salvador, etc). Students were asked to evaluate the quality of these fabrics.

The swatches were cut from the same cloth, so they were identical. But as you can guess, students read differences that were not there, often born from prejudices of these countries. Schooler's findings were published in an academic journal and spawned a new area of research.

When discussing country-of-origin labels, we should first recognize the complexity of production, which today is global. Sheep can be reared in Australia, their hairs spun into yarn in Scotland, the fabric woven in China, and then the material is finished in England.

That's just for the fabric. For a tailored jacket, consider the global supply chain for buttons, padding, canvassing, haircloth, threads, lining, and assembly (which can also include patternmaking, cutting, sewing, etc).

Country of origin labels don't capture this complexity.

Country of origin labels don't capture this complexity.

Countries also differ on how they regulate labeling. In Italy, a garment can almost be entirely made abroad and then finished in Italy to quality for a "made in Italy" label. In the US, rules are stricter, but few people check, so a lot of mislabeling goes unnoticed.

But let's get into the specific claims. Does a country of origin label tell you anything about whether an item is high quality, made with fair wages, or isn't just fast fashion?

https://x.com/TheFireman430/status/1847509570656358438

I will address these claims in reverse order. First, many people misuse the term fast fashion to mean "cheap clothing" when it in fact refers to a specific mode of production. I will not rehash this here but instead direct you to read this thread below.

https://x.com/dieworkwear/status/1740118466437480825

Once you understand what is "fast fashion," you can more accurately identify it on the market. And when you peer inside some of these garments, you may find a "made in USA" tag. These Fashion Nova jeans—which are fast fashion—were made in Los Angeles' garment district.

These jeans can be made in the US because of a system called piecerate, which pays workers per operation instead of how much time they work. This allows factories to run as sweatshops and sidestep labor laws (including min wage). From my piece in The Nation:

Such factories are quite common. In 2016, the US Federal Dept of Labor found that 85% of the Los Angeles garment factories in their sample were violating wage laws, which resulted in $1.3 million back wages owed to 865 workers. Conditions were deplorable.

thenation.com/article/archiv…

thenation.com/article/archiv…

Shopping high-end doesn't necessarily guarantee fair wages or ethical conditions either. Some of the Italian factories that produce for well-known luxury names have violated labor laws. This has been a continual issue in Italian fashion. A headline from Business of Fashion:

OK, what about quality? Fifty years ago, I would have agreed with you: Clothes made in the US and Western Europe were generally better than their Chinese counterparts. But much has changed.

A friend of mine is a bespoke tailor, Senior Vice President of one of the largest US suit factories, and the president of a trade organization for designers and tailors. He had this to say about Chinese production in 2011:

Here's Antonio Ciongoli, founder of 18 East and former Ralph Lauren designer, talking about J. Crew, which is mostly made in China:

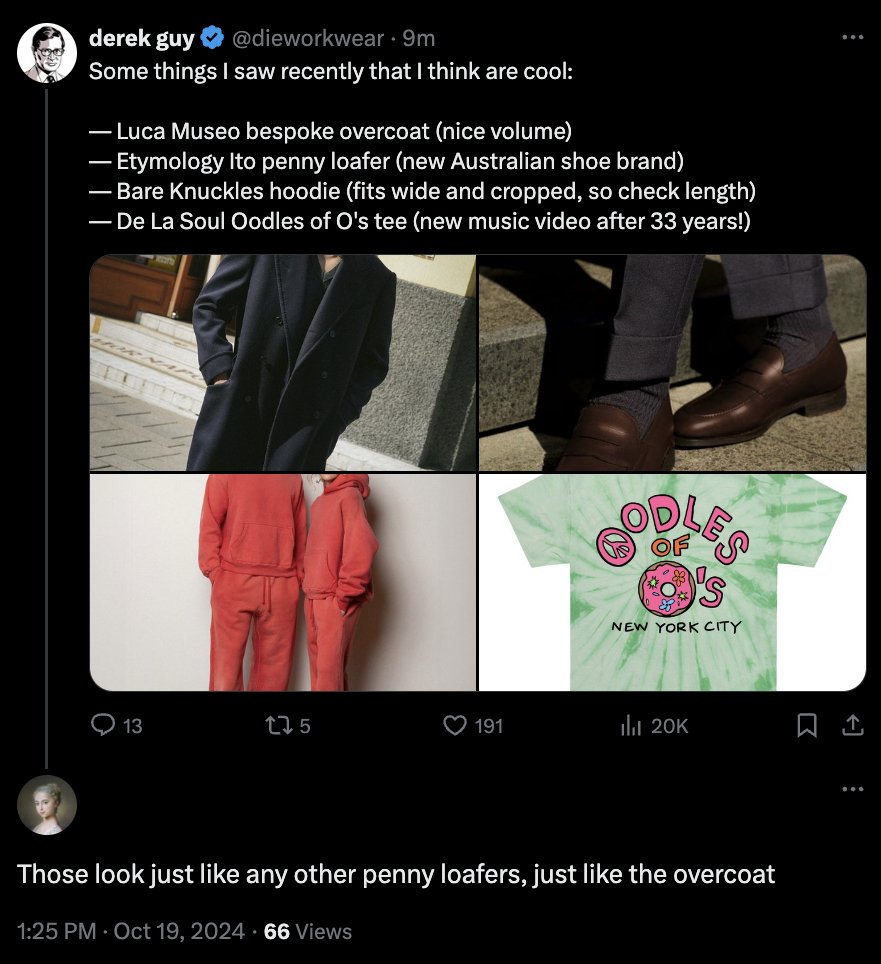

"The call outs of bad quality always highlight to me just how little most people know about what real quality actually looks like."

"The call outs of bad quality always highlight to me just how little most people know about what real quality actually looks like."

Some of the best garment production nowadays is being done in China. For instance, these RRL shawl collar cardigans have no peer. They are hand-knitted using unique silk-linen yarns that have tremendous depth.

Here are bespoke, hand-tailored garments from Atelier BRIO Pechino, a small tailoring operation based in Beijing. This is levels above most tailoring operations in the United States—certainly any made-to-measure shop, but even most bespoke (of what's left in the US)

It's even better than Loro Piana. Here's a cashmere Loro Piana Roadster jacket—one of their flagship products—produced after the company was acquired by LVMH. Notice the pocket construction. Suede trim under flap is purely decorative.

On this bespoke BRIO sport coat—made from Loro Piana cashmere-silk fabric—the suede trim has been added to the pocket's top edge. This stops the edge from fraying, which is useful in high-traffic areas like a pocket when the material is delicate. Adding this takes skilled work.

The questions should always be: Can you spot quality? Do you know the different components that go into quality production? Can you spot the difference between full grain vs corrected grain leather, Goodyear welt vs glued on sole? Do you know the length of the fibers in the yarn?

It's important to recognize that non-Western countries often hold within them rich craft traditions. In India, there are textile weavers and printers who are engaging in techniques no longer possible in the UK (as well as their own local traditions). This craft is beautiful.

US production is not always great. When Brooks Brothers owned the Garland Shirt Company, which was based in Garland, North Carolina, they brought in consultants from their overseas Asia partner, TAL. Garland was just not running right, and they needed TAL's help.

Many brands privately tell me that US factories are lacking in some way—poor quality control, lack of skilled labor, not enough tech upgrades, etc. The Asian-made counterparts are often better.

Of course, there's also a lot of bad stuff that comes out of China, such as SHEIN.

Of course, there's also a lot of bad stuff that comes out of China, such as SHEIN.

When thinking about quality, fast fashion, and labor, we should address them directly and not collapse them into county-of-origin labels. There are good and bad things made everywhere. Using tariffs in this way is just old school protectionism and prejudice.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh