I'll tell you what goes on here. 🧵

https://twitter.com/PerfideAlbion/status/1846962201946460546

Harris Tweed is the only fabric that's legally protected. Just as Bordeaux wine has to be from the Bordeaux region of France, any fabric bearing this stamp has to be woven in the Outer Hebrides, finished in the Outer Hebrides, and made from wool dyed & spun in the Outer Hebrides.

The Outer Hebrides is Scotland's Wild West. In his 1973 book, WH Murray wrote that the region's most important climatic feature are the gale force winds. If you ask an islander for tomorrow's forecast, he won't say dry, wet, or sunny, but quote a figure from the Beaufort Scale.

For that reason, the local blackface sheep have a thicker, coarser, stronger fleece. They used to be the only wool source for Harris Tweed, although nowadays, the fabric can be woven from wool sourced from Cheviots. They have a softer fleece.

The production of Harris Tweed used to be done by crofters (such as tenant farmers), who used the material for living and trading. It was not uncommon for someone to pay rent with blankets or lengths of clò-mòr. Which is to say there were hundreds or thousands of producers.

Today, this production is consolidated into three mills. They do the work of grading and sorting the fleece, washing it, dyeing and carding the fibers, and then spinning them into yarn. This material is then arranged in the form of beams or bobbins. From National Geographic:

In the video above, you can see how the wool is dyed into brilliant colors. This material is then mixed together. When spun into yarn and woven into cloth, you get this interesting depth that's not just flat brown or yellow, but a color that reflects the richly colored landscape.

The main thing to know about Harris Tweed is that it's the most widely used hand-loomed fabric for men's tailoring. By hand-loomed, I mean the mills send bobbins or beams to independent weavers who work with just their hands and feet (no automation or electricity).

This weaving typically takes place in a shed located steps from the weaver's home. In the olden days, weavers used Hattersley single-width looms. Today, some operate Bonas-Griffith double-width looms to produce softer, lighter fabrics (ones made from that Cheviot woo)l.

In the past, men primarily did the weaving, while women did the waulking (the soaking of tweed in urine, then stretching and thumping it to shrink and soften it; material would later be hand washed). Women sang songs in chorus to lighten the work and keep rhythm.

Today, that finishing process is done industrially and without urine, although the weaving is done in the same was it has for generations: by foot and hand on an old loom stored in a drafty shed. From an old Esquire series:

The thing about Harris Tweed is that it's ... rough. It's pricklier than other types of tweeds partly because it's typically made from that locally sourced blackface sheep wool (stronger, coarser wool). IMO, it's best for outerwear such as sport coats and overcoats.

If you get trousers, you will need to get them fully lined. Or you need to have your own fleece, which is to say hairy legs.

If you want something lighter, softer, and more comfortable, you can try Breanish tweed.

If you want something lighter, softer, and more comfortable, you can try Breanish tweed.

Breanish doesn't qualify as Harris Tweed bc it's not purely made from locally sourced wool, but it's still handloomed on the island using an old single-width loom that was purchased with a bottle of whisky. Since they use a mix of materials, like cashmere, the cloth is softer.

So that's what happens on that island. If you're buying custom clothes, then Harris Tweed can be sourced from Harrisons Fine Worsted. If you're buying ready-to-wear, many clothiers will stock Harris Tweed sport coat: Drake's, Ben Silver, J. Press, Ralph Lauren, among the many.

Harris Tweed is certainly not the only type of tweed. The garments below are made in other regions and from other types of wool. But it's the only one that's legally protected. If you see something with the Harris Tweed logo (the orb), you now know the backstory.

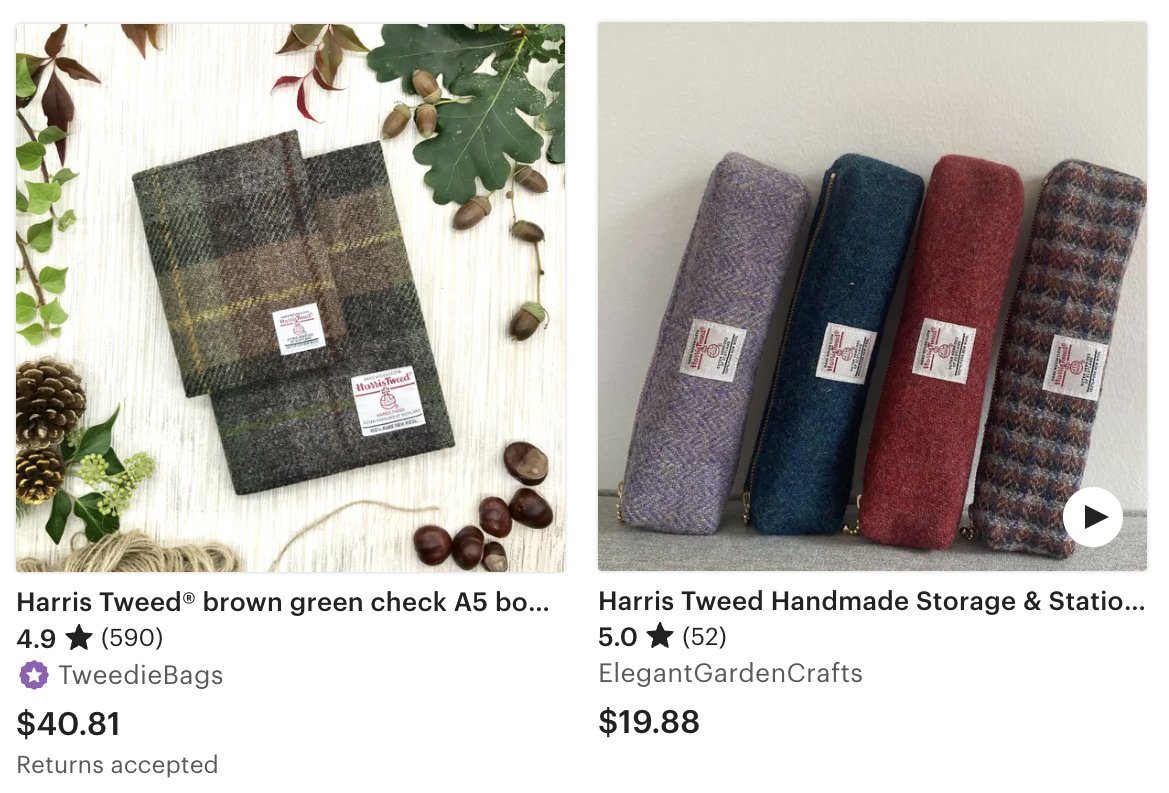

Forgot to add: if you want something relatively affordable, lots of Etsy sellers make notebooks, eyewear sleeves, and pen cases from Harris Tweed.

And while not made from Harris Tweed or even tweed at all, I also like Waverley Scotland notebooks, which have nice tartan covers.

And while not made from Harris Tweed or even tweed at all, I also like Waverley Scotland notebooks, which have nice tartan covers.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh