The obvious example of how The Sort exposes you to incompetence is that nowadays, competent people don't go into the public sector all that often.

This is a mixed bag: while the government is a poor use of human capital, it needs some to avoid holding back the rest of society.

This is a mixed bag: while the government is a poor use of human capital, it needs some to avoid holding back the rest of society.

There are also a lot of fairly menial service sector jobs that you'll run into all the time, and these are less obviously, but no less problematized by The Sort.

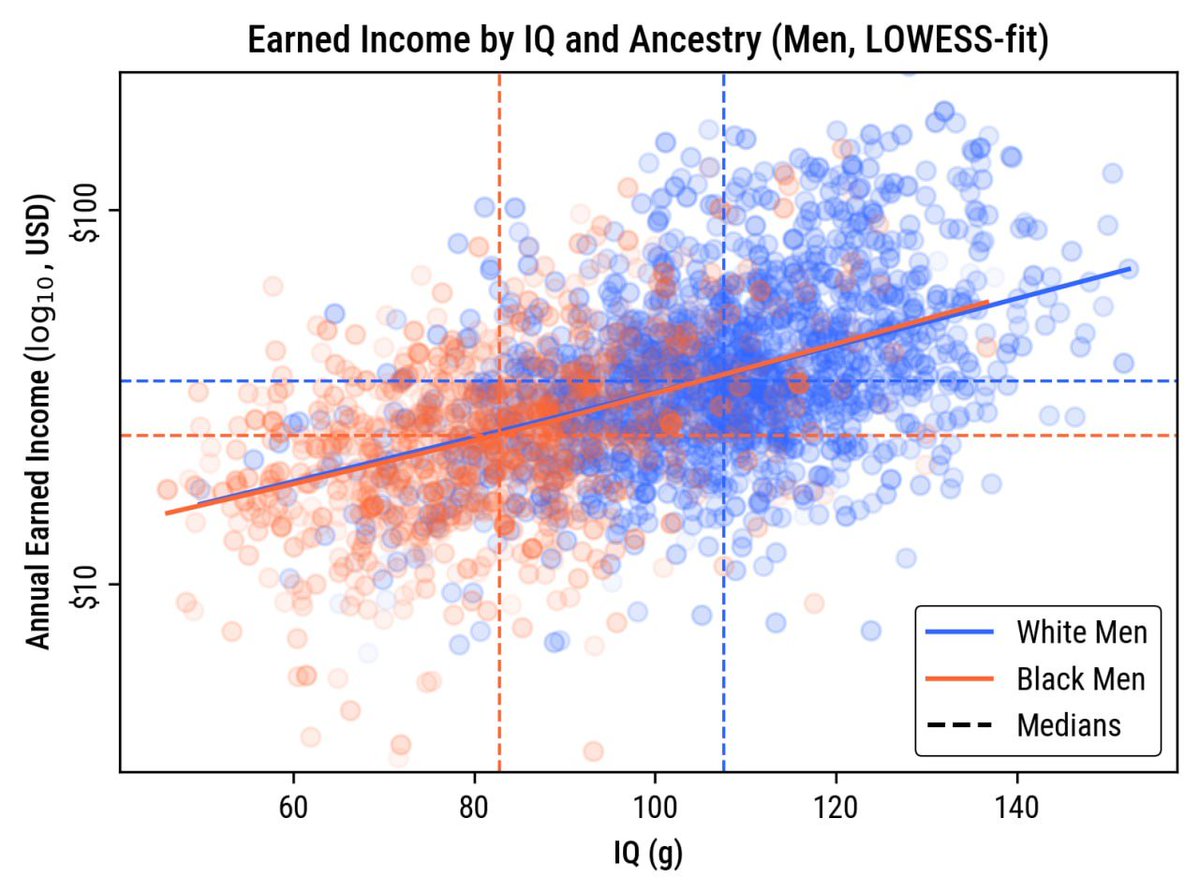

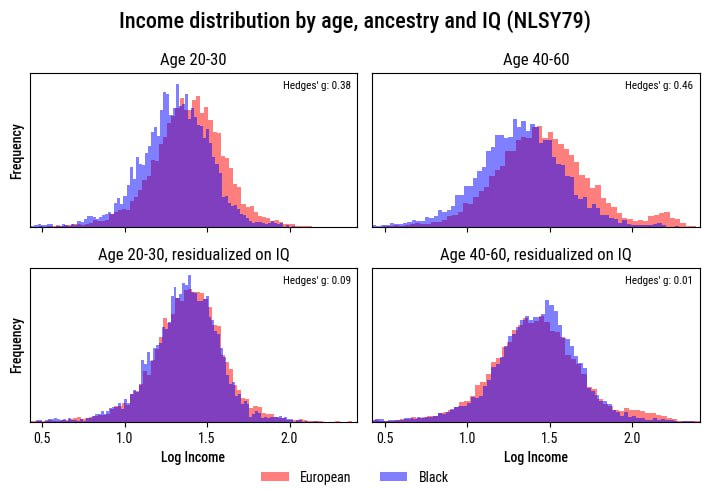

Why? Because in the past, socioeconomic status was less cognitively stratified.

You can still see this today in many developing economies, where intelligence is slowly becoming more related to socioeconomic status as markets develop and opportunity expands.

You can still see this today in many developing economies, where intelligence is slowly becoming more related to socioeconomic status as markets develop and opportunity expands.

The improvements to The Sort mean that fewer and fewer smart people are born into and remain in bad conditions.

But that also means that fewer and fewer smart people spend a long time in menial service sector jobs.

But that also means that fewer and fewer smart people spend a long time in menial service sector jobs.

Accordingly, the quality of the work in those jobs is worse than if the job had more intelligent people working it.

Why? The first reason is that smarter people just do jobs better: They make fewer mistakes, operate more efficiently, often even have higher moral standards, etc.

Why? The first reason is that smarter people just do jobs better: They make fewer mistakes, operate more efficiently, often even have higher moral standards, etc.

The second reason is that, because smart people do jobs better, they teach less smart people how to do the job better, either directly or by example.

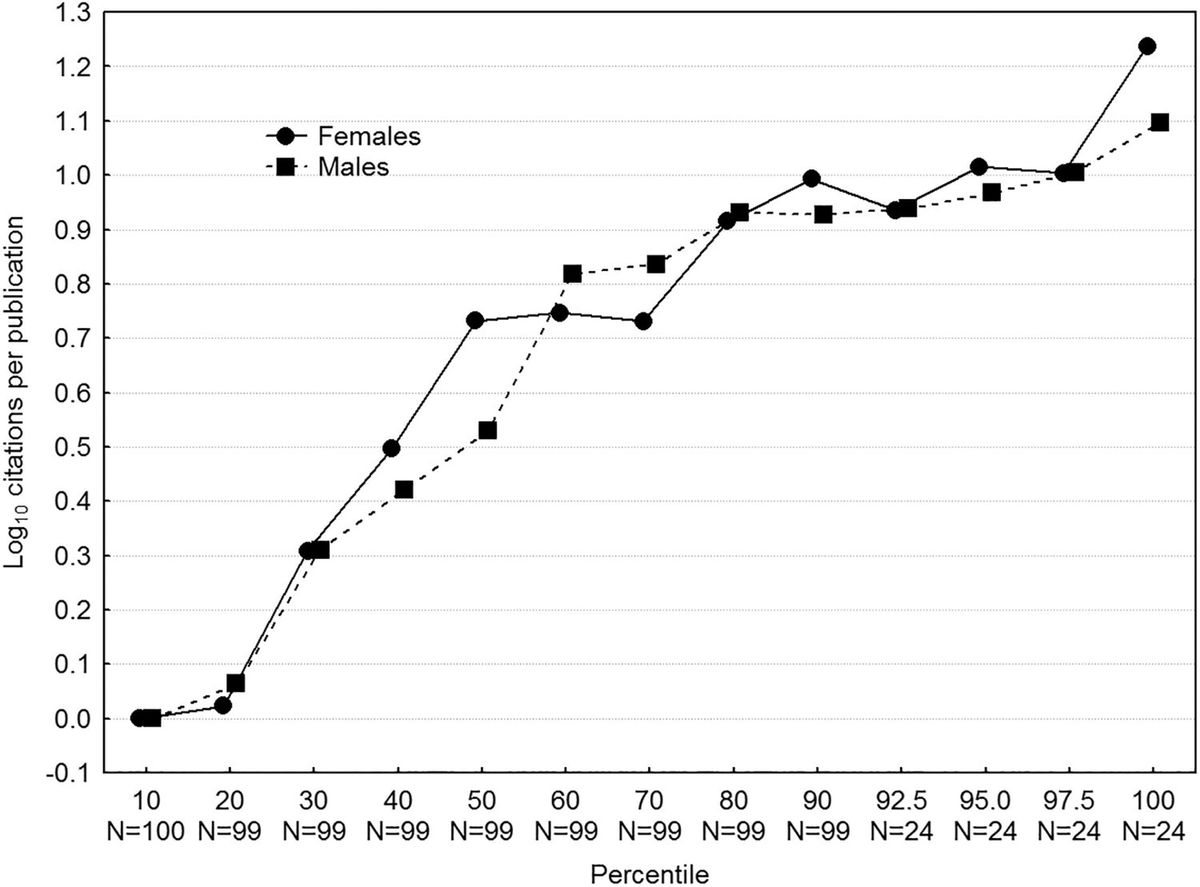

When you have more and less intelligent people play games, combining them brings up the less able.

When you have more and less intelligent people play games, combining them brings up the less able.

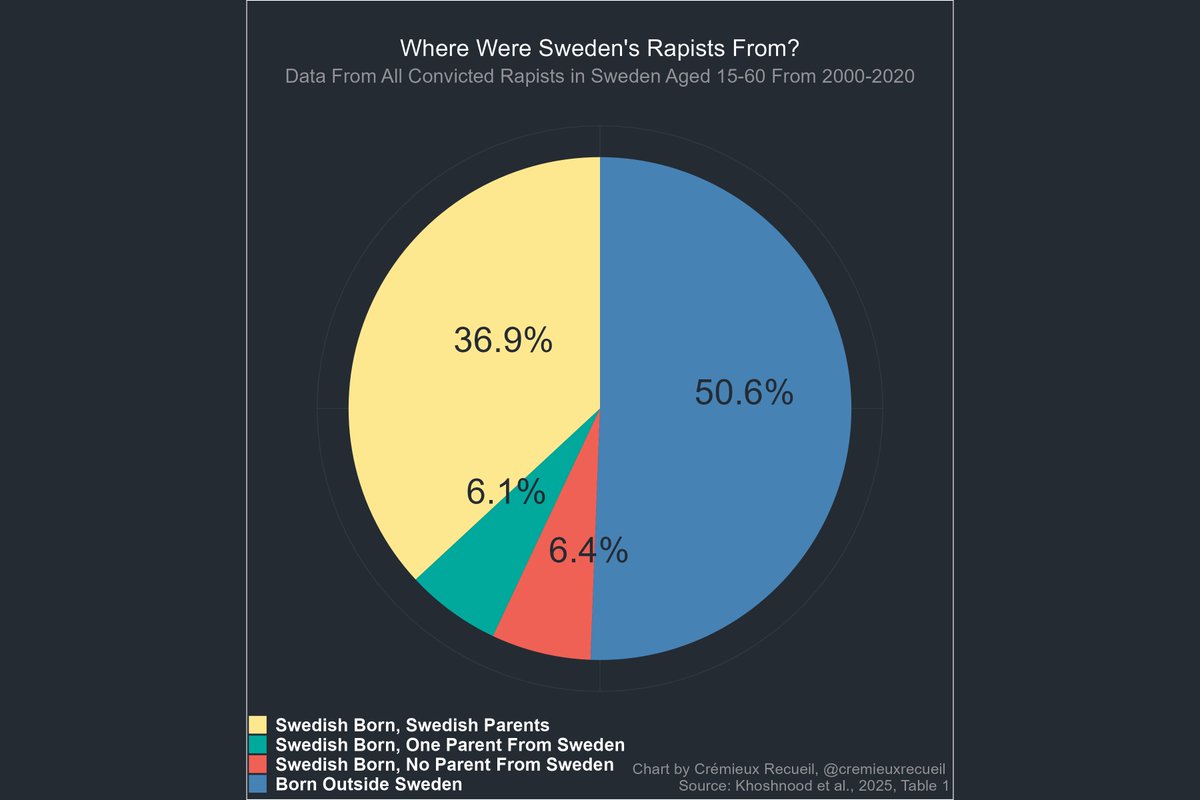

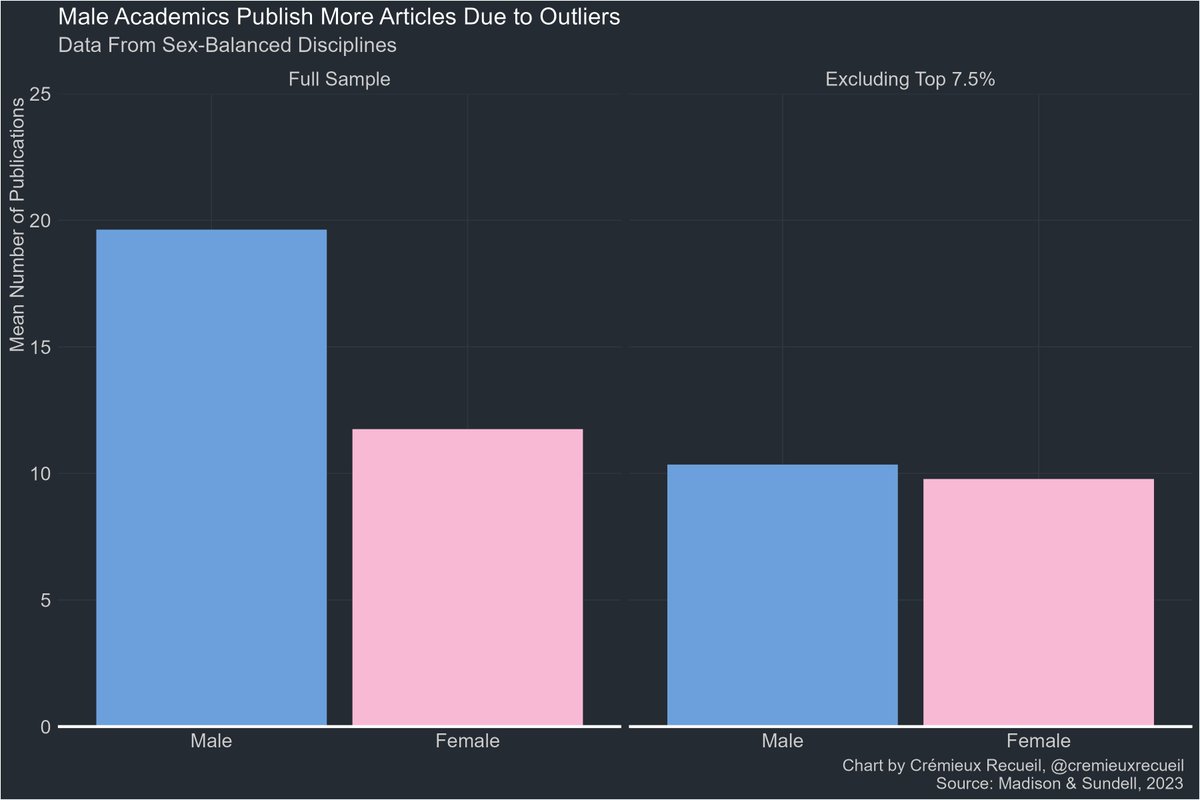

https://x.com/cremieuxrecueil/status/1654633491378716672

In effect, many jobs are becoming more and more of left tail-exclusive jobs, with the effect being that they're done worse and worse, making your life harder and wasting more of your time when you run into them.

But it doesn't have to be this way!

But it doesn't have to be this way!

Ever been to a Buc-ee's?

They're Texas' amazing gas station/car wash combo stores, and they're known

(A) Being pleasant, and

(B) Very publicly paying their employees well.

They're Texas' amazing gas station/car wash combo stores, and they're known

(A) Being pleasant, and

(B) Very publicly paying their employees well.

If you've been to a Buc-ee's you might have noticed that they offer discounted gas if you wash your car.

Their car washes are very long and the wait times are minimal compared to other offerings.

They have minimal human involvement.

Their car washes are very long and the wait times are minimal compared to other offerings.

They have minimal human involvement.

Because Buc-ee's embraces productivity-improving tools and builds, and pushes their employees to be efficient, they can afford to pay them well and to pass on lots of savings to customers, and they also pass on saved time over other car washes.

Productivity enhancements that eliminate the involvement of human labor have the opportunity to cut out increasingly-inefficient human components of jobs.

If the carwash is nearly fully automated, the wages can be respectable and slow' human involvement can be minimized.

If the carwash is nearly fully automated, the wages can be respectable and slow' human involvement can be minimized.

And where will the people currently working those jobs go?

Take manufacturing employment. When industrial robots are installed, employment goes down in that area, but up more in non-manufacturing jobs.

The disemployed move jobs.

Take manufacturing employment. When industrial robots are installed, employment goes down in that area, but up more in non-manufacturing jobs.

The disemployed move jobs.

Wages tend to go up. They tend to move to better jobs, or at least jobs that are less dangerous, less monotonous, and which are better compensated.

And crucially, that left tail? It might move closer to the rest of the cognitive pack, meaning its members can skill up.

And crucially, that left tail? It might move closer to the rest of the cognitive pack, meaning its members can skill up.

Automation might be even more of an engine of progress and life improvement than people generally assume, and it might make all of our lives better off by fixing some of the downsides of The Sort.

Thanks, robots!

Thanks, robots!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh