What does labor-saving technology do to workers? Does it make them poor? Does it take away their jobs?

Let's review!

First: Most papers do support the idea that technology takes people's jobs.

Let's review!

First: Most papers do support the idea that technology takes people's jobs.

This needs qualified.

Most types of job-relevant technology do take jobs, but innovation is largely excepted, because, well, introducing a new innovation tends to, instead, give employers money they can use to hire people.

Most types of job-relevant technology do take jobs, but innovation is largely excepted, because, well, introducing a new innovation tends to, instead, give employers money they can use to hire people.

But if technology takes jobs, why do we still have jobs?

Simple: Because through stimulating production and demand, it also reinstates laborers!

This is supported by the overwhelming majority of studies:

Simple: Because through stimulating production and demand, it also reinstates laborers!

This is supported by the overwhelming majority of studies:

This reinstatement effect is largely consistent across types of technology, with innovations still looking a bit odd.

That is the weirdest category of technology besides "other", so roll with it.

That is the weirdest category of technology besides "other", so roll with it.

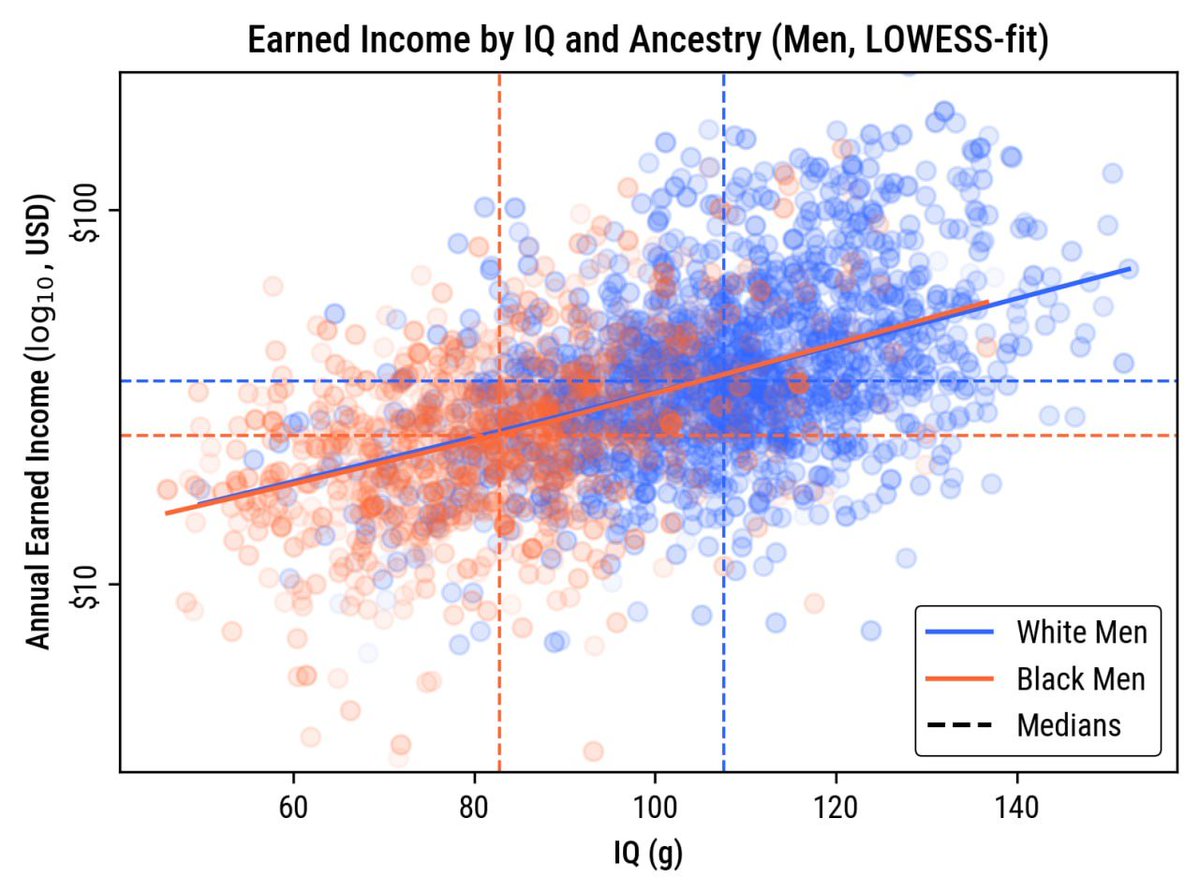

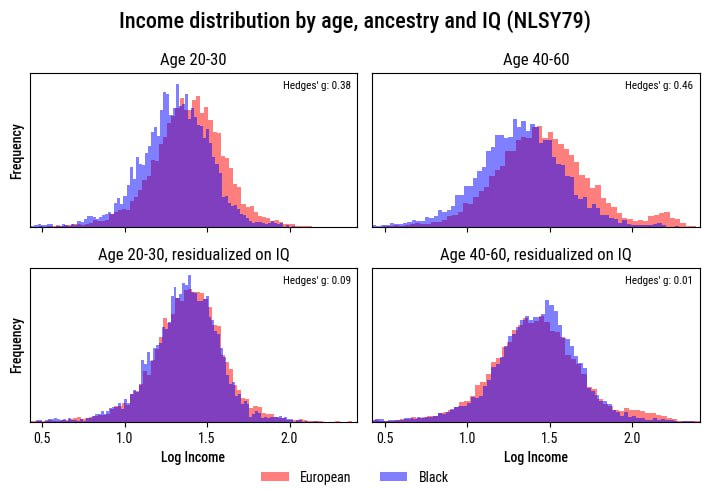

Now the operative question is, if workers lose their jobs and end up reinstated in other jobs, what happens to their incomes?

Well, technology introduction tends to boost incomes!

Well, technology introduction tends to boost incomes!

But, you might ask, whose income is boosted? Because if reinstatement affects far smaller numbers of workers than replacement, some people might still be getting shafted.

Well, the net employment effects of technology are highly ambiguous:

Well, the net employment effects of technology are highly ambiguous:

If we look across types of technology the picture I mentioned above for innovation-style technology shows up again: many studies suggest it's good for employment.

The reason impacts on net employment are so ambiguous is because they really have to be qualified.

For example, in general, when robots cause manufacturing employment to fall, there's a compensatory effect on service-sector employment that's at least as large in magnitude:

For example, in general, when robots cause manufacturing employment to fall, there's a compensatory effect on service-sector employment that's at least as large in magnitude:

What makes that impact so interesting is another way it's qualified: It's smaller in industries more at-risk of offshoring.

In other words, industrial robots save American jobs from going overseas.

In other words, industrial robots save American jobs from going overseas.

Industrial robots also contribute directly to reshoring. In other words, when Americans buy robots to do their manufacturing, Mexicans lose their jobs.

The welfare impact for domestic workers is positive. Not so for Mexicans, but that's just how things go.

The welfare impact for domestic workers is positive. Not so for Mexicans, but that's just how things go.

Overall, labor-saving technology is clearly good, and the longer we delay adopting it, the poorer we will be relative to the world in which we picked it up immediately.

Want to know more? Check out my latest article: cremieux.xyz/p/workers-for-…

Want to know more? Check out my latest article: cremieux.xyz/p/workers-for-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh