"Alors, c’est la guerre"

Many think they know about WW2 and the important battles; but what do you know about the War's biggest upset?

Follow me down this thread to learn why Winston Churchill reportedly said: “Greeks do not fight like heroes; heroes fight like Greeks”.

Many think they know about WW2 and the important battles; but what do you know about the War's biggest upset?

Follow me down this thread to learn why Winston Churchill reportedly said: “Greeks do not fight like heroes; heroes fight like Greeks”.

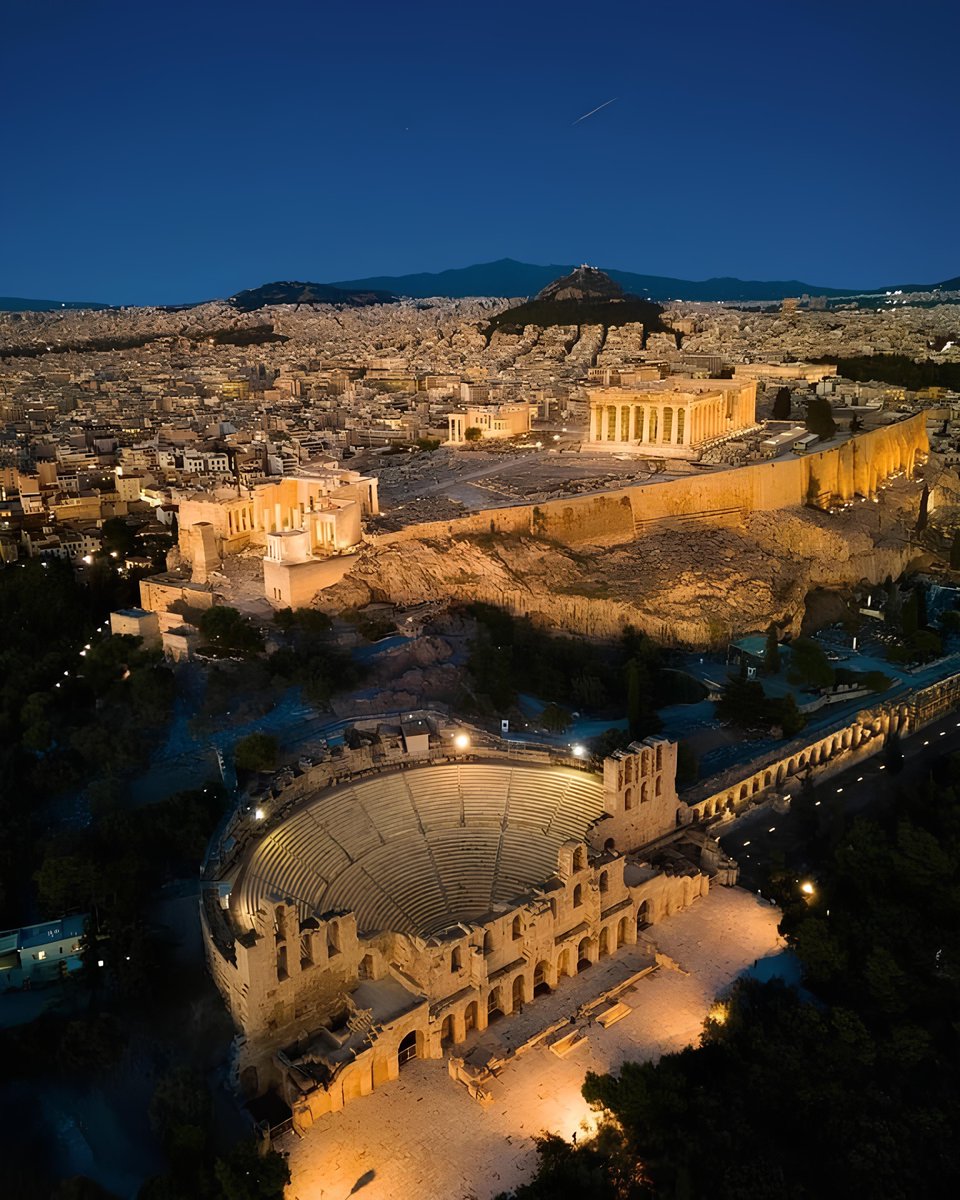

In the early days of WWII, a seemingly impossible feat unfolded in the mountains of Greece. Against all odds, the Greeks repelled a larger, better-equipped Italian force, creating one of the most inspiring upsets of the war.

By October 1940, a clown called Benito Muzzolini was eager to assert Italy’s dominance in the Balkans, hoping to match the Painter’s swift victories across Europe and revive the Roman Empire.

Greece, strategically located and relatively isolated, seemed the perfect target and a historical enemy. He confidently boasted of a quick and easy victory, dismissing the Greeks as militarily weak. This “easy victory within 2 weeks” would become a nightmare.

Greece, strategically located and relatively isolated, seemed the perfect target and a historical enemy. He confidently boasted of a quick and easy victory, dismissing the Greeks as militarily weak. This “easy victory within 2 weeks” would become a nightmare.

The Italians had been actively trying to provoke a war, even sinking a Greek ship in its harbor, during a Holy day: The day of Virgin Mary.

The Italian submarine Delphino sneaked in the Aegean waters and torpedoed the Greek destroyer “Ellie” in Tinos, an island which is revered and dedicated to Virgin Mary.

This was an unholy and ultimately provocative action but the Greek government was apprehensive of declaring war against the Axis.

The Italian submarine Delphino sneaked in the Aegean waters and torpedoed the Greek destroyer “Ellie” in Tinos, an island which is revered and dedicated to Virgin Mary.

This was an unholy and ultimately provocative action but the Greek government was apprehensive of declaring war against the Axis.

Ioannis Metaxas, Greece’s Prime Minister and authoritarian leader from 1936, was a staunch nationalist who foresaw the storm brewing in Europe and worked to prepare Greece for potential conflict.

Though his regime was authoritarian, banning political parties and censoring the press, Metaxas invested heavily in military readiness and was largely supported by the Greeks.

Though his regime was authoritarian, banning political parties and censoring the press, Metaxas invested heavily in military readiness and was largely supported by the Greeks.

Anticipating an Axis invasion, he strengthened Greece's defensive infrastructure, including fortifying the Metaxas Line, a series of fortifications along the Bulgarian border.

This defense system, inspired by France’s Maginot Line, would later prove crucial during the German invasion. Metaxas also reorganized the Greek army, modernized its arsenal, and boosted production of munitions to maximize the nation's limited resources.

This defense system, inspired by France’s Maginot Line, would later prove crucial during the German invasion. Metaxas also reorganized the Greek army, modernized its arsenal, and boosted production of munitions to maximize the nation's limited resources.

At 3 AM on October 28, Italy issued an ultimatum to Greece, demanding the right to occupy strategic sites. Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas replied with a simple but defiant “Alors, c’est la guerre” (then, this is war – in French) which the Greeks saw as “OXI” (No, in Greek).

Within hours, Italian troops poured over the border from Albania, expecting little resistance. Yet, instead of crumbling, the Greeks stood their ground—and fought back. It was GO TIME.

Within hours, Italian troops poured over the border from Albania, expecting little resistance. Yet, instead of crumbling, the Greeks stood their ground—and fought back. It was GO TIME.

The Italians had already occupied the protectorate they had created before, the land called today Albania; the local Albanians were more than eager to join the Axis and fight against the Greeks, seeing this as an opportunity to expand their influence in Northern and Southern Epirus, which was – and still is - ancient Hellenic soil. They were in for a treat themselves too!

Italians were already deployed in large numbers, dressed as civilians (to achieve maximum surprise).

Italians were already deployed in large numbers, dressed as civilians (to achieve maximum surprise).

The Italian forces outnumbered the Greeks 3-to-1, possessing superior weaponry, air support, and tanks. But the Greeks had something harder to measure: a fierce determination to defend their homeland and honor their legacy.

Greek forces, composed largely of civilians who rushed to volunteer and became hoplites (as in ancient times – the word itself means “man bearing weapon”), knew the difficult mountain terrain and leveraged it skillfully, ambushing Italian forces and nullifying much of their technological advantage.

Greek forces, composed largely of civilians who rushed to volunteer and became hoplites (as in ancient times – the word itself means “man bearing weapon”), knew the difficult mountain terrain and leveraged it skillfully, ambushing Italian forces and nullifying much of their technological advantage.

The Italians expected a second Roman conquest of Greece while the Greeks saw this as payback time and a second Thermopylae.

Papagos, the Greek commander in Chief said: “In our struggle, we fought with the fire of our souls, not with weapons. Weapons are of little use without the bravery and sacrifice of men willing to die for their homeland.”

Another field marshal, Tsolakoglou said: “We were not supposed to win. The world thought we would surrender in days. But in those mountains, we showed the world what freedom and love of country can inspire in men.”

The Greeks would not let it go.

Papagos, the Greek commander in Chief said: “In our struggle, we fought with the fire of our souls, not with weapons. Weapons are of little use without the bravery and sacrifice of men willing to die for their homeland.”

Another field marshal, Tsolakoglou said: “We were not supposed to win. The world thought we would surrender in days. But in those mountains, we showed the world what freedom and love of country can inspire in men.”

The Greeks would not let it go.

As the Italian campaign stalled, winter descended upon the mountains of Epirus and Albania. Temperatures plummeted, and the mountainous terrain became treacherous.

The Greeks, more accustomed to these harsh conditions, pressed their advantage, driving the Italians back and even capturing Italian-held territory in Albania. Italian soldiers struggled with supply shortages and unfamiliar winter conditions, while Greek troops showed remarkable resilience and tactical flexibility.

The Greeks, more accustomed to these harsh conditions, pressed their advantage, driving the Italians back and even capturing Italian-held territory in Albania. Italian soldiers struggled with supply shortages and unfamiliar winter conditions, while Greek troops showed remarkable resilience and tactical flexibility.

By December, the Greeks had pushed the Italians back 50 kilometers into Albanian territory. Greece became the first country in WWII to successfully launch a counteroffensive against an Axis power, astonishing the world.

Reports spread of Greek soldiers charging Italian lines, their courage shocking an Italian army that was supposed to have overpowered them.

Reports spread of Greek soldiers charging Italian lines, their courage shocking an Italian army that was supposed to have overpowered them.

Mussolini’s “easy victory” turned into a protracted disaster. Italian forces were humiliated, morale plummeted, and reinforcements couldn’t break the Greek chads.

The setback embarrassed Italy and strained their resources, forcing their Austrian dad to divert German forces for an invasion of Greece in the spring of 1941, stalling the Soviet Union invasion (which probably determined the outcome of the war eventually).

The setback embarrassed Italy and strained their resources, forcing their Austrian dad to divert German forces for an invasion of Greece in the spring of 1941, stalling the Soviet Union invasion (which probably determined the outcome of the war eventually).

The Germans launched operation “Marita” demolishing Yugoslavia in mere days and then attacking Greece with the help of their Bulgarian allies; Greece was now alone against Italians and Germans and their lackeys, Albanians and Bulgarians.

Most of the Greek forces were already engaged deep in Albania, kicking Italian ass and the Metaxa’s line was only there to defend the Northern borders of Greek Macedonia.

Most of the Greek forces were already engaged deep in Albania, kicking Italian ass and the Metaxa’s line was only there to defend the Northern borders of Greek Macedonia.

The dogged resistance of the Greek troops in those battles surprised the German troops; they were already warned: “You are fighting against warriors who are the descendants of the heroes of Marathon, of Thermopylae, and the gods of Olympus. The resistance of the Greeks is not of the common type.”

There was an instance where Greeks defended one of their forts, called Rupel against the German onslaught.

There was an instance where Greeks defended one of their forts, called Rupel against the German onslaught.

The fort's design, with underground tunnels and concealed bunkers, allowed the Greeks to weather heavy bombardment and counterattack German advances.

Greek soldiers repelled the Germans at multiple points and even inflicted significant casualties on the attackers, a feat that stunned the German commanders. The Germans notified the Greek commander that the Hellenic High Command had surrendered and they should obey; the Greek replied:

“we only take orders from our superiors and the fight will continue. Any attempt to approach the fortress will be crushed”.

After a while the Germans came back and ordered them to surrender the fort; the Greek commander again replied:

“forts are meant to be taken, not surrendered”.

Glorious basterds; eventually the order came from the Greek central command. The German forces were so surprised by the Greek fighting spirit that allowed them to leave unscathed, with their flags.

The commander’s name was Georgios Duratsos.

Greek soldiers repelled the Germans at multiple points and even inflicted significant casualties on the attackers, a feat that stunned the German commanders. The Germans notified the Greek commander that the Hellenic High Command had surrendered and they should obey; the Greek replied:

“we only take orders from our superiors and the fight will continue. Any attempt to approach the fortress will be crushed”.

After a while the Germans came back and ordered them to surrender the fort; the Greek commander again replied:

“forts are meant to be taken, not surrendered”.

Glorious basterds; eventually the order came from the Greek central command. The German forces were so surprised by the Greek fighting spirit that allowed them to leave unscathed, with their flags.

The commander’s name was Georgios Duratsos.

The Austrian Painter himself acknowledged the Greek fighting spirit over any other opponent he had faced. He said:

“The historical justice requires me to state that of all our opponents, only the Greeks fought with bold courage and the highest disregard for death.”

He also reportedly said that “If it were not for the bravery of the Greeks and their resistance in Albania, we would not have delayed our Russian campaign.”

“The historical justice requires me to state that of all our opponents, only the Greeks fought with bold courage and the highest disregard for death.”

He also reportedly said that “If it were not for the bravery of the Greeks and their resistance in Albania, we would not have delayed our Russian campaign.”

Although eventually occupied by Axis forces, Greece’s resistance remains one of WWII’s most remarkable stories. Greeks would pay high a price for their offenses; Greece was separated into 3 occupation zones (German, Italian, Bulgarian) and would suffer severe starvation.

Greece’s initial victory against Italy and their unyielding defense in the face of the German blitzkrieg symbolized defiance against oppression, inspiring resistance movements across Europe.

To this day, Greeks celebrate Oxi Day on October 28, honoring the moment they defied fascist aggression with a single, powerful word: “No.”

Greece’s initial victory against Italy and their unyielding defense in the face of the German blitzkrieg symbolized defiance against oppression, inspiring resistance movements across Europe.

To this day, Greeks celebrate Oxi Day on October 28, honoring the moment they defied fascist aggression with a single, powerful word: “No.”

The Greek victory over Italy was a triumph of courage, strategy, and national pride over a seemingly unbeatable foe. It reminded the world that small nations, when united in purpose and spirit, could stand up to even the most formidable enemies.

The Greeks’ improbable stand against Italy altered the course of the war and left a lasting legacy of bravery in the face of tyranny.

The Greeks’ improbable stand against Italy altered the course of the war and left a lasting legacy of bravery in the face of tyranny.

You may now get a grasp why the Greek madmen do not celebrate “Victory Day” or anything like the other vegan Europeans; they celebrate the day their leader had the balls of steel to represent the Hellenic nation and its history defiantly, saying “NO”, on the 28th of October 1940.

Now you know. ΖΗΤΩ ΤΟ ΕΘΝΟΣ!

Now you know. ΖΗΤΩ ΤΟ ΕΘΝΟΣ!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh