There are a lot of misconceptions about witch trials.

Opponents of religion often point to the Church’s handling of witch hunts, hoping to paint a simplistic picture of an “evil” medieval Church.

But the real story is more complicated…🧵(thread)

Opponents of religion often point to the Church’s handling of witch hunts, hoping to paint a simplistic picture of an “evil” medieval Church.

But the real story is more complicated…🧵(thread)

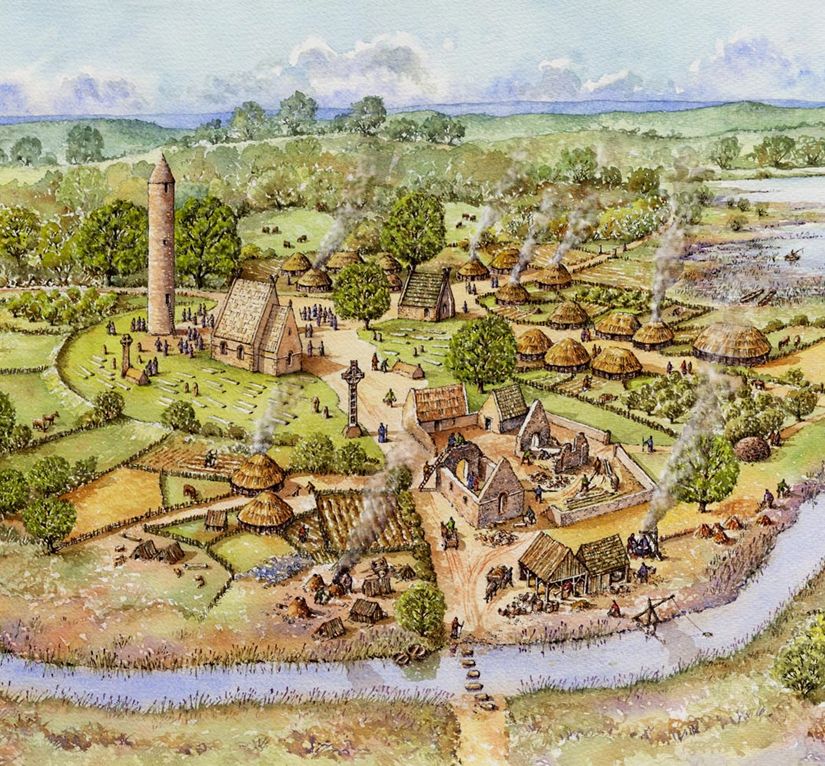

Sorcery has been around since ancient times, but witchcraft — loosely defined as the practice of black (or evil) magic to harm others — really came to head once Christianity became the dominant religion in the West.

And though they’re often portrayed as dark age occurrences, witch trials only became popular in the late medieval and early modern period (~1400-1700).

Early on, the Church rejected witchcraft as a real phenomenon and deemed it a “pagan superstition”.

Early on, the Church rejected witchcraft as a real phenomenon and deemed it a “pagan superstition”.

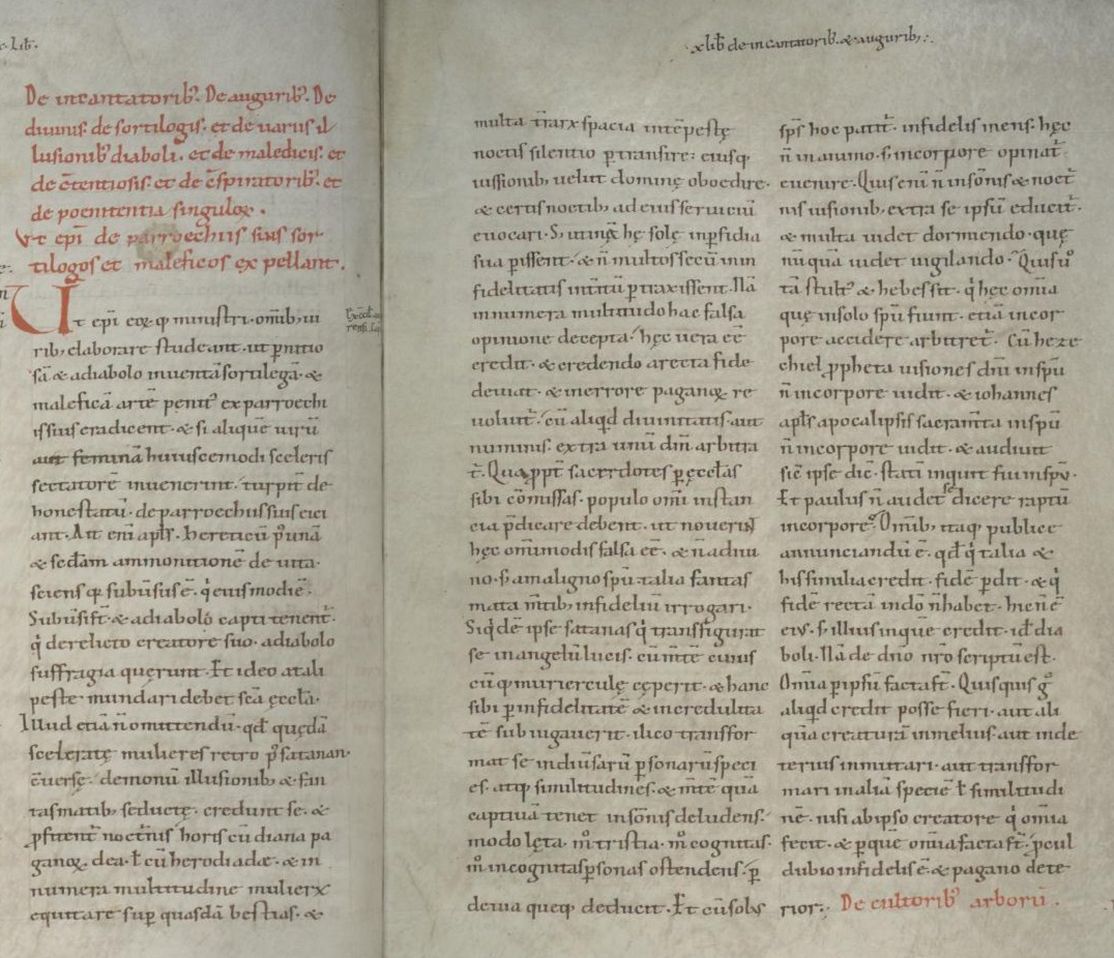

The Canon Episcopi, a passage of canon law dating to the 10th-11th centuries, states that “dream visions” were often mistaken as physical manifestations of demonic power.

It urges priests to teach their congregations that these visions are simply figments of the imagination.

It urges priests to teach their congregations that these visions are simply figments of the imagination.

The text, however, condemns the "pernicious art of divination and magic" and confirms that an early form of witchcraft was being attempted by certain “wicked women” who were practicing devil worship rather than having any real magical powers.

The Canon Episcopi remained the most authoritative text regarding witches and was cited as late as the 17th century by skeptics of witchcraft.

Despite the teaching, accusations of witchcraft still occurred, and the Inquisition was a ready means to investigate suspected witches…

Despite the teaching, accusations of witchcraft still occurred, and the Inquisition was a ready means to investigate suspected witches…

In 1329, an inquisitor in France sentenced a Carmelite friar, Peter Recordi, to life imprisonment for conjuring demons, seducing women, and sacrificing a butterfly to Satan. The sentence frequently uses the word “sortilegia” — a Latin term that became synonymous with witchcraft.

Witch trials remained uncommon in the 15th century but growing opposition to Canon Episcopi mounted as several prominent clergymen wrote arguments against the teaching, claiming to respond to the growing challenge of “disbelief in the reality of demonic activity in the world.”

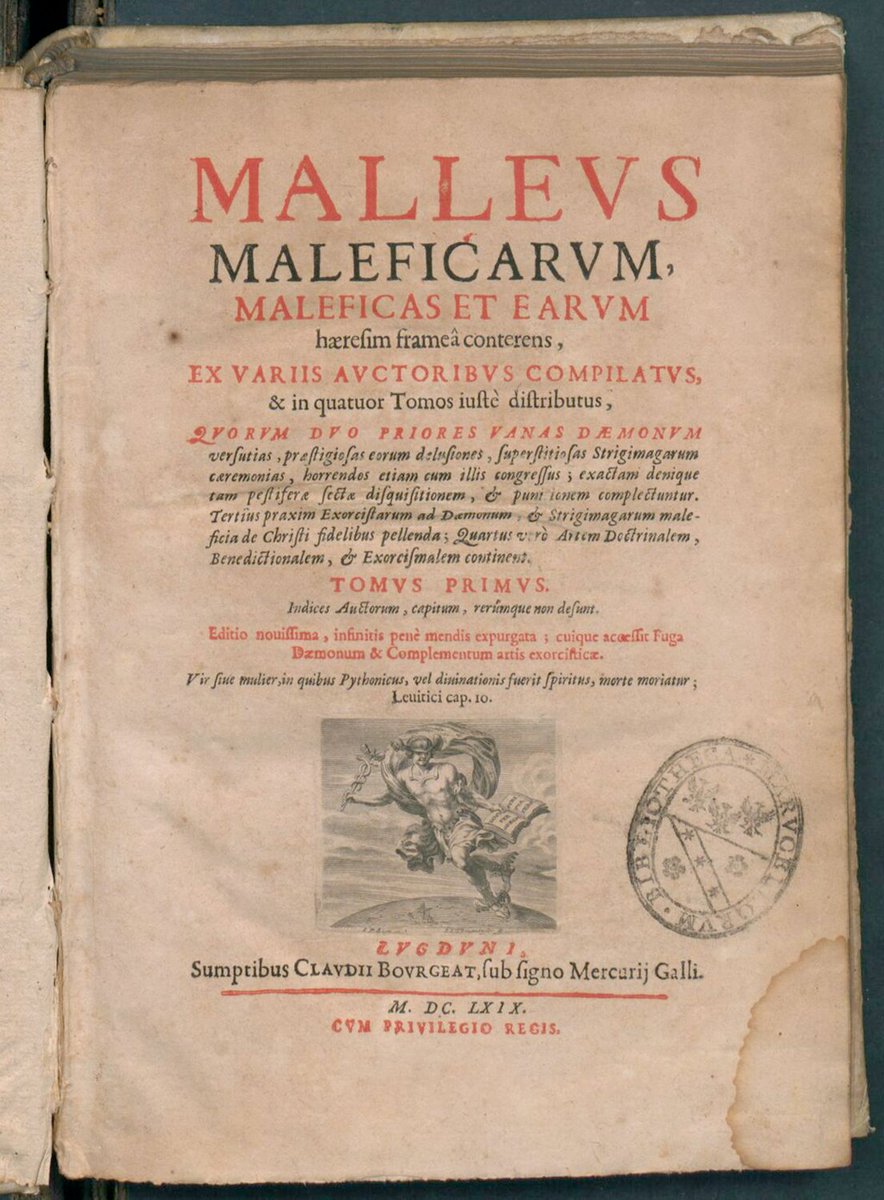

But the most influential text popularizing witchcraft as a real threat was a work entitled Malleus Maleficarum — “Hammer Against Witches.”

Written by Dominican priest Heinrich Kramer in 1484, it was essentially a witch fighting manual.

Written by Dominican priest Heinrich Kramer in 1484, it was essentially a witch fighting manual.

The work argued that sorcery should be viewed as a form of heresy by the Church, meaning that the death penalty could be used since heresy was punishable by death.

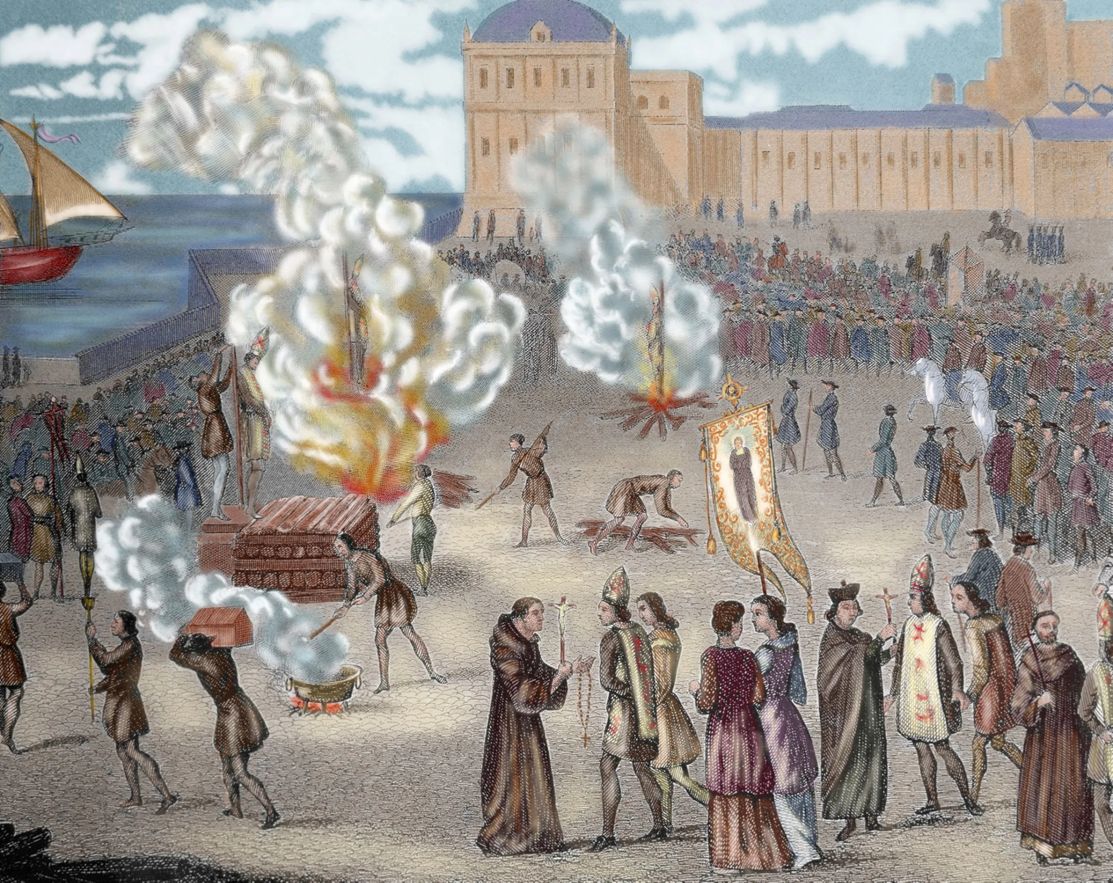

Heretics at this time were often burned at the stake, and the manual suggested the same for witches.

Heretics at this time were often burned at the stake, and the manual suggested the same for witches.

Kramer was described as “senile and crazy” by his local bishop before being expelled from his diocese, and contemporary theologians rejected his work on the grounds it was inconsistent with the Church’s methods and doctrines of demonology.

But the work only grew in popularity…

But the work only grew in popularity…

The Malleus popularized the conception of the witch as an evil woman — a description that still persists today — and jump-started a fascination in witchcraft. Kramer was even invited by the head of the Dominicans to Venice and gave a series of lectures on the topic.

Malleus Maleficarum continued to be printed into the 16th and 17th centuries, when witch-craze reached its peak in Europe.

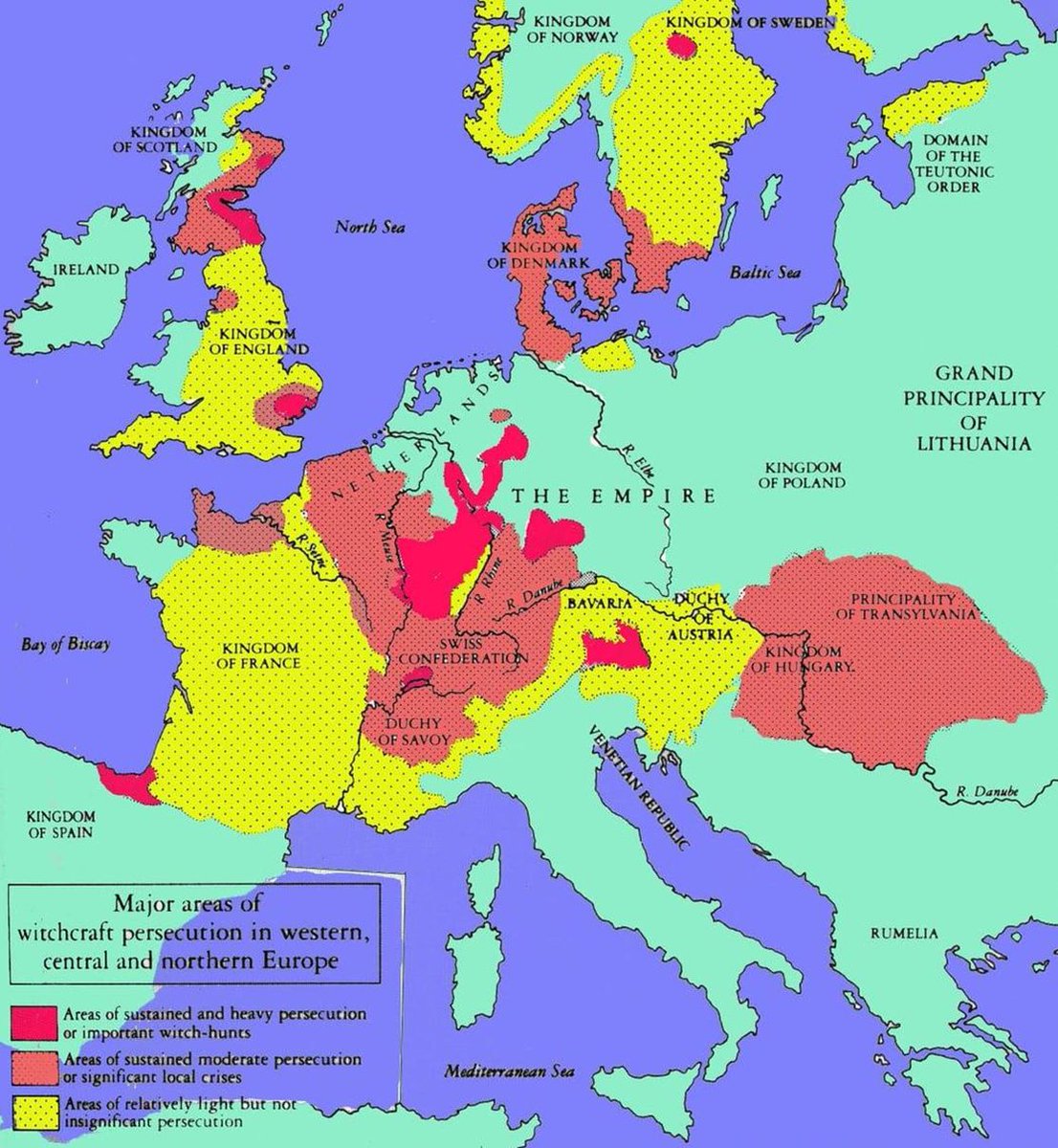

Southern Germany in particular was a hotbed of activity, with significant trials taking place in Trier, Fulda, Eichstätt, Würzburg, and Bamberg.

Southern Germany in particular was a hotbed of activity, with significant trials taking place in Trier, Fulda, Eichstätt, Würzburg, and Bamberg.

Contemporary chronicler Herman Löher claimed the people of Germany were “the most terrified people on earth, since the false witch trials affect the German episcopal lands incomparably more than France, Spain, Italy or Protestants.”

Though Löher claimed witch hysteria was heavier in Catholic areas, Protestant nations had their fair share of witch trials, too.

And in some cases even royalty was involved…

And in some cases even royalty was involved…

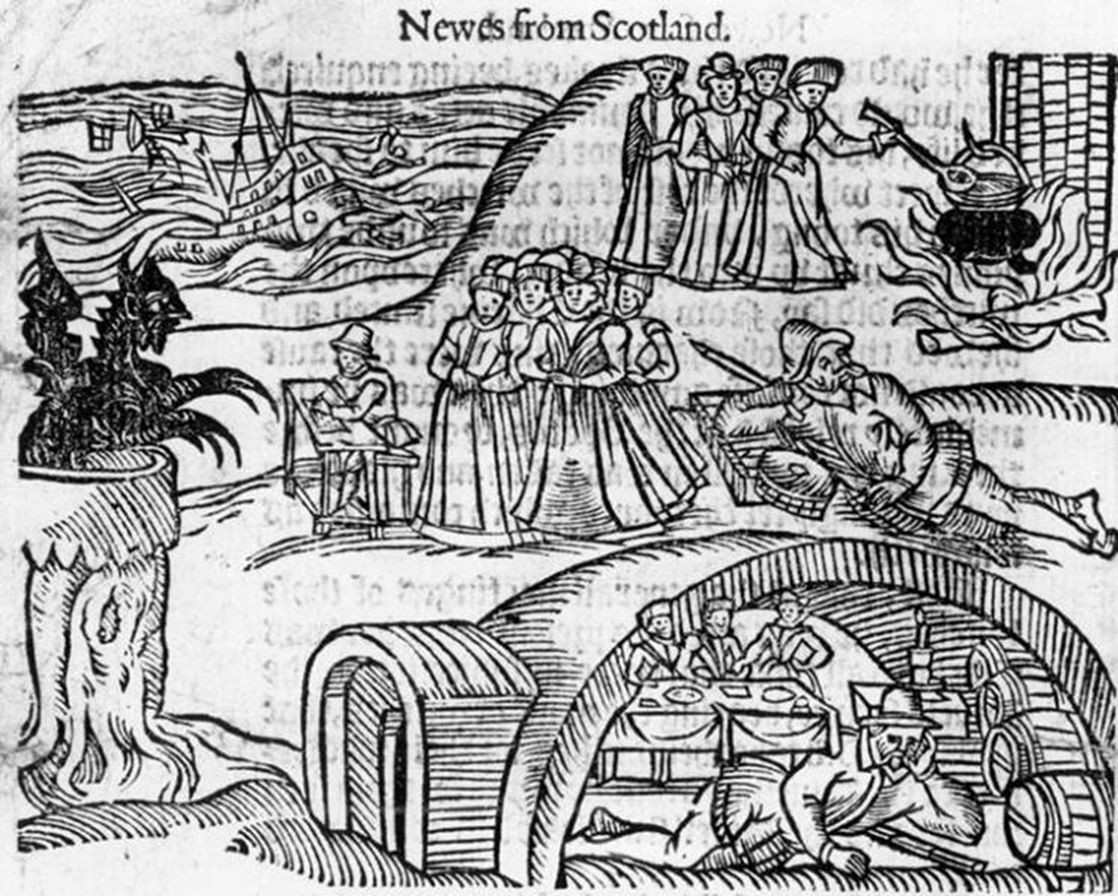

In 1590 James VI, king of Scotland, developed a fear of witches after he and his bride, Anne of Denmark, were caught in “contrary winds” (storms supposedly summoned by witches) en route to Scotland.

James had the suspected perpetrators brought to him shortly after for trial.

James had the suspected perpetrators brought to him shortly after for trial.

One earl, Francis Stewart, and others were arrested and charged with arranging to kill the king via sorcery by summoning the inclement weather.

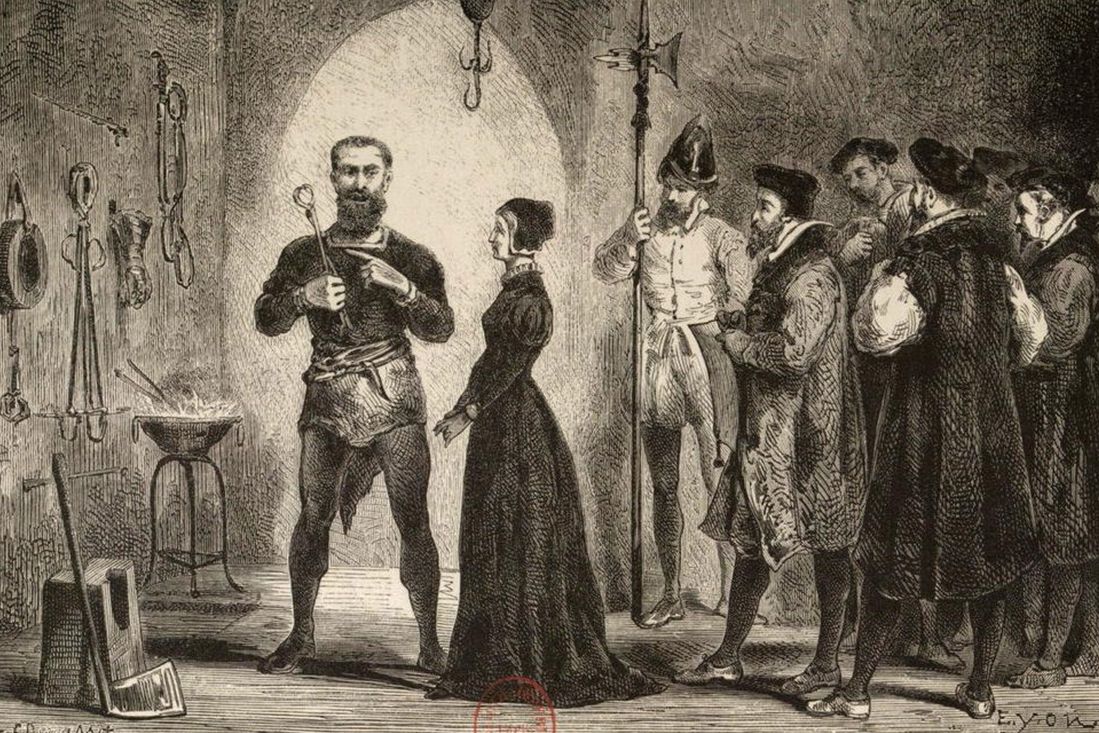

The king then set up a royal commission to hunt witches, recommending torture in dealing with suspects.

The king then set up a royal commission to hunt witches, recommending torture in dealing with suspects.

Later in 1597, James published a book exposing the menaces that witches posed to society and the methods they used to harm mankind. Entitled Daemonologie, it supported the practice of witch hunting and included a study of demons.

The king’s ordeal and book supposedly influenced Shakespeare’s Macbeth — both the play’s description of witches and Scottish setting were inspired by passages in Daemonologie and the witch trials in which James was involved.

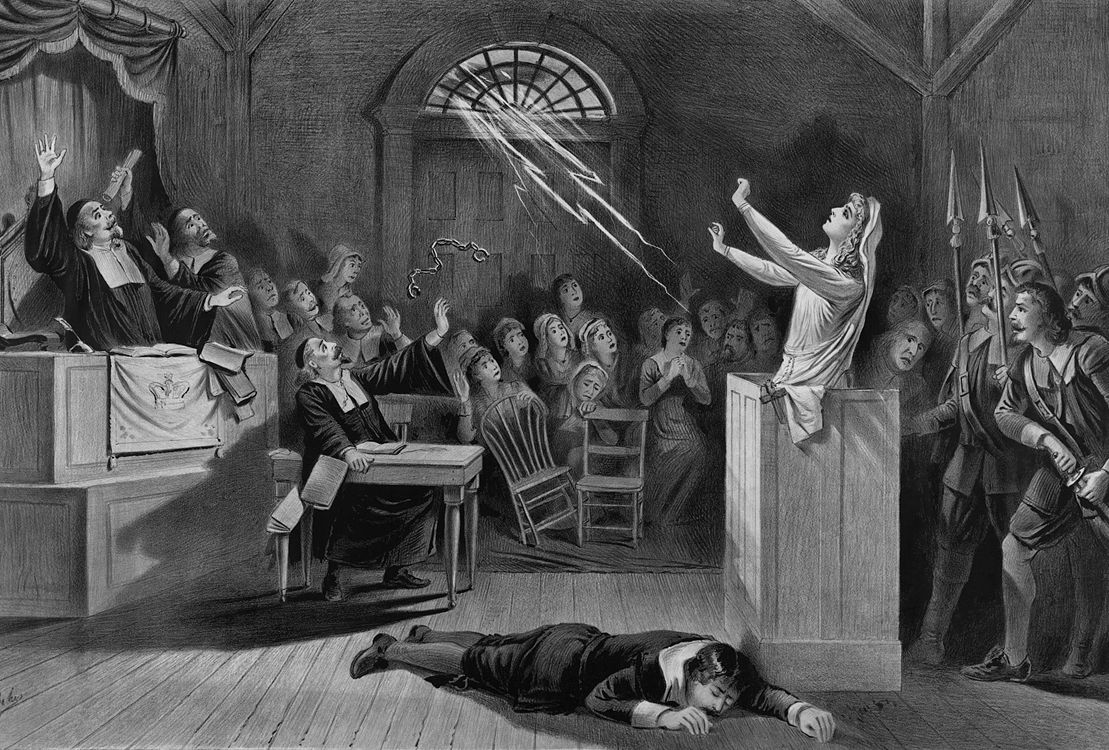

In the late 17th century, witch trials reached well beyond Europe, most notably the Salem witch trials in Massachusetts.

But witch-mania was already on the decline, and skepticism toward the phenomenon as well as critics of witch-hunters’ methodology were winning the argument.

But witch-mania was already on the decline, and skepticism toward the phenomenon as well as critics of witch-hunters’ methodology were winning the argument.

In 1635, the Roman Inquisition even admitted that most investigations were poorly executed, declaring "the Inquisition has found scarcely one trial conducted legally."

And in time it was discovered that many of the reported numbers of witch trials were vastly overblown…

And in time it was discovered that many of the reported numbers of witch trials were vastly overblown…

One of the most popular works to massively overestimate the amount of witch trials during the middle ages was entitled “Histoire de l'inquisition en France”, written by French author Étienne-Léon de Lamothe-Langon.

Writing his work in 1829, Lamothe-Langon described mass witch trials in southern France that ended in hundreds of executions.

He claimed to have access to original sources and inquisitional records, and his book proved highly influential, instilling the idea that the medieval period was full of superstitious zealots into the modern zeitgeist.

It was only discovered in the 1970’s that his “sources” were highly questionable if not outright forgeries.

But by the time mainstream historians rejected his work, the damage was done—hysterical witch hunts were already firmly ingrained into the popular image of the middle ages

But by the time mainstream historians rejected his work, the damage was done—hysterical witch hunts were already firmly ingrained into the popular image of the middle ages

So just how prevalent were witch hunts and executions?

Well, getting exact numbers is always difficult given the time period, but historian Brian Levack, known for his ”Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft” estimates roughly 100,000 trials from 1400-1775.

Well, getting exact numbers is always difficult given the time period, but historian Brian Levack, known for his ”Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft” estimates roughly 100,000 trials from 1400-1775.

100,000 certainly isn’t a small number, but given it covers nearly 400 years and the entirety of Europe and the British Americas, it's not the bloodbath that's often imagined.

Keep in mind only around half actually resulted in a guilty verdict.

Keep in mind only around half actually resulted in a guilty verdict.

In short, the medieval and early modern periods weren’t necessarily brimming with overly superstitious mobs looking to burn witches; rather, witch hunts were a more sporadic phenomenon, and the Church actually taught against the practice for a long period of time.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh