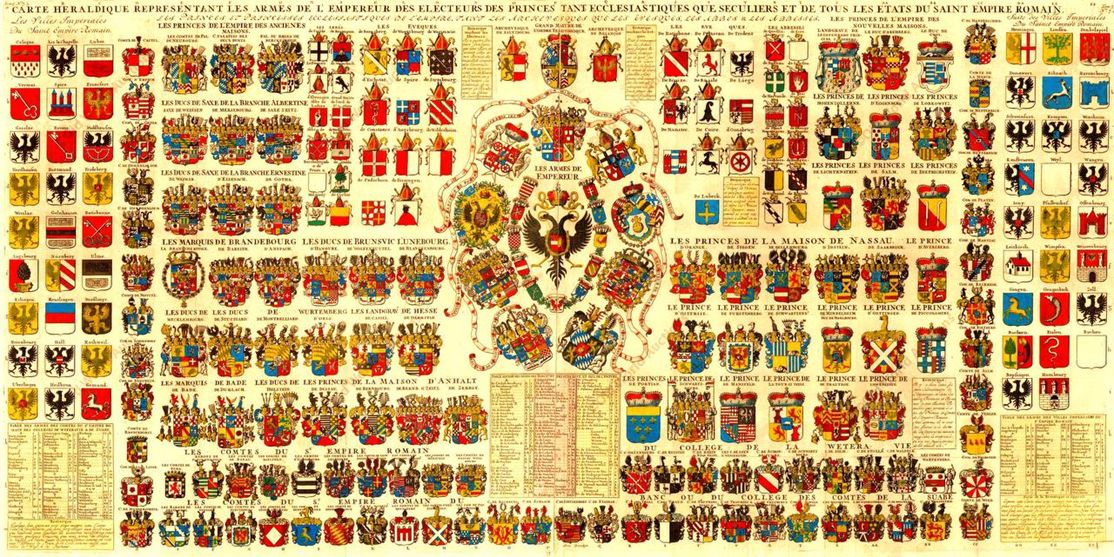

The Holy Roman Empire lasted ~1000 years, and it looked like this:

How did such a fractured political entity last so long?

It has to do with a concept called “subsidiarity”, and it holds the key to implementing responsible government today 🧵 (thread)

How did such a fractured political entity last so long?

It has to do with a concept called “subsidiarity”, and it holds the key to implementing responsible government today 🧵 (thread)

Voltaire famously derided the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) as “neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire”, but what couldn't be denied was its longevity.

Existing from 800-1806, it was birthed before William the Conqueror invaded England and continued on after the American Revolution.

Existing from 800-1806, it was birthed before William the Conqueror invaded England and continued on after the American Revolution.

It’s considered one of the longest lasting empires in history, a feat of particular intrigue when one considers its central geographical location and lack of natural defensible borders.

So what was its secret? Why did the HRE last so long — surviving massive political turmoil and even wars within its borders — while other nations came and went?

To answer this question we first need to understand the concept of subsidiarity…

To answer this question we first need to understand the concept of subsidiarity…

Subsidiarity is a Catholic principle of governance developed by Pope Leo XIII in his 1891 encyclical Rerum novarum (“Revolutionary Change”) as an attempt to bridge the gap between capitalism and socialism.

Later Pope Pius XI defined it:

“a fundamental principle of social philosophy…that one should not withdraw from individuals and commit to the community what they can accomplish by their own enterprise and industry.”

“a fundamental principle of social philosophy…that one should not withdraw from individuals and commit to the community what they can accomplish by their own enterprise and industry.”

Essentially it means that matters should be handled by the lowest or least centralized competent authority.

Political decisions should be made locally — a decentralized government ensures those closest to the problem have the most control.

Political decisions should be made locally — a decentralized government ensures those closest to the problem have the most control.

Decentralization, and thus subsidiarity, has an inherently stabilizing effect as government has many checks and balances and can’t be undermined by a few poor decisions from leadership.

In the spirit of philosopher Nassim Taleb, decentralized systems are “anti-fragile”.

And the HRE was exactly this.

Let’s explore how the it’s structure implemented subsidiarity…

And the HRE was exactly this.

Let’s explore how the it’s structure implemented subsidiarity…

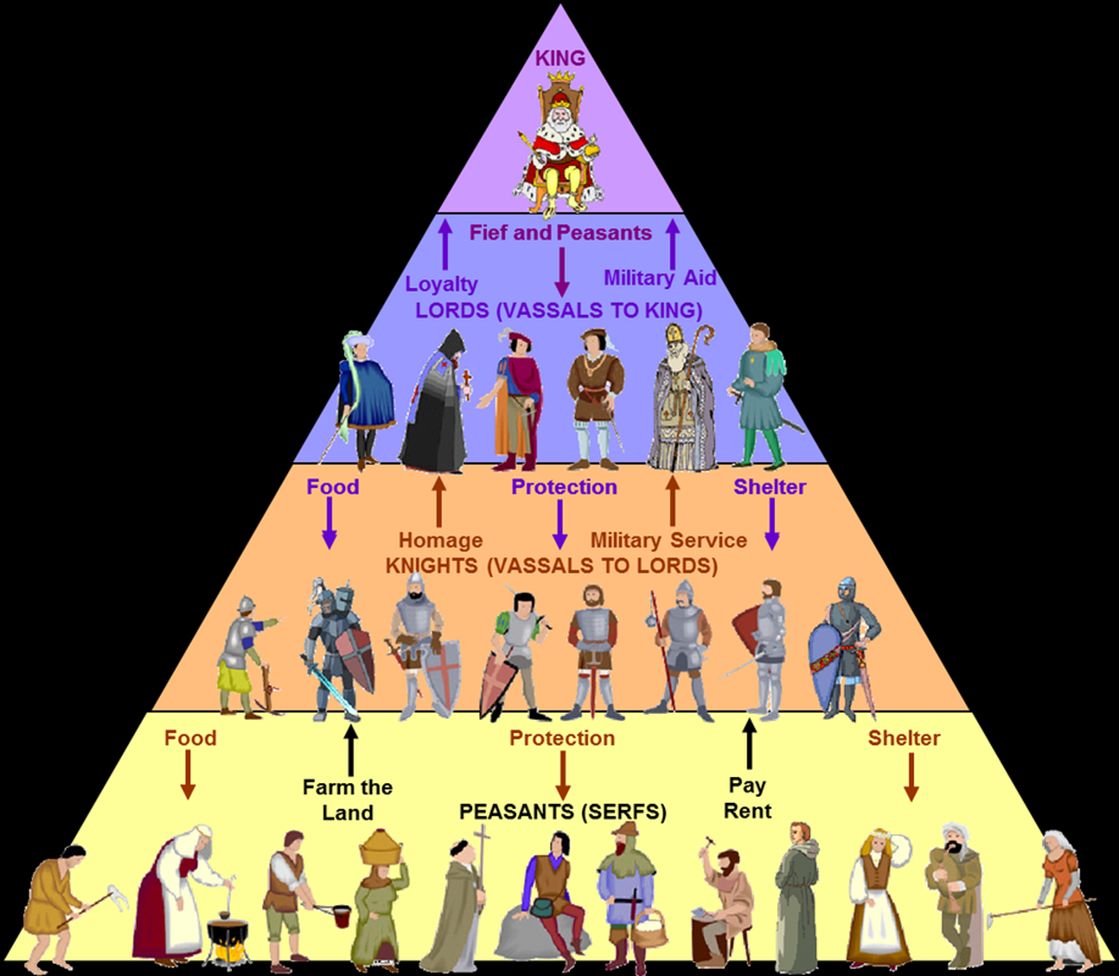

The HRE, like many medieval states, was feudal. This meant that society was structured around three key concepts: lords, vassals, and fiefs (lands).

There were various forms of feudalism within the empire, but we’ll stick to the basic model.

There were various forms of feudalism within the empire, but we’ll stick to the basic model.

A lord was a noble who owned lands; a vassal was someone the lord granted possession of land in exchange for service to the lord. Vassals would get land and protection, while the lord would get a vassal he could call upon for military service—this was the “feudal relationship.”

The system is best envisioned as a pyramid with a king (the ultimate “lord”) at the top, and a series of vassalages cascading down to the peasantry. Lower classes granted upper classes resources or military service, while upper classes granted lower classes protection and land.

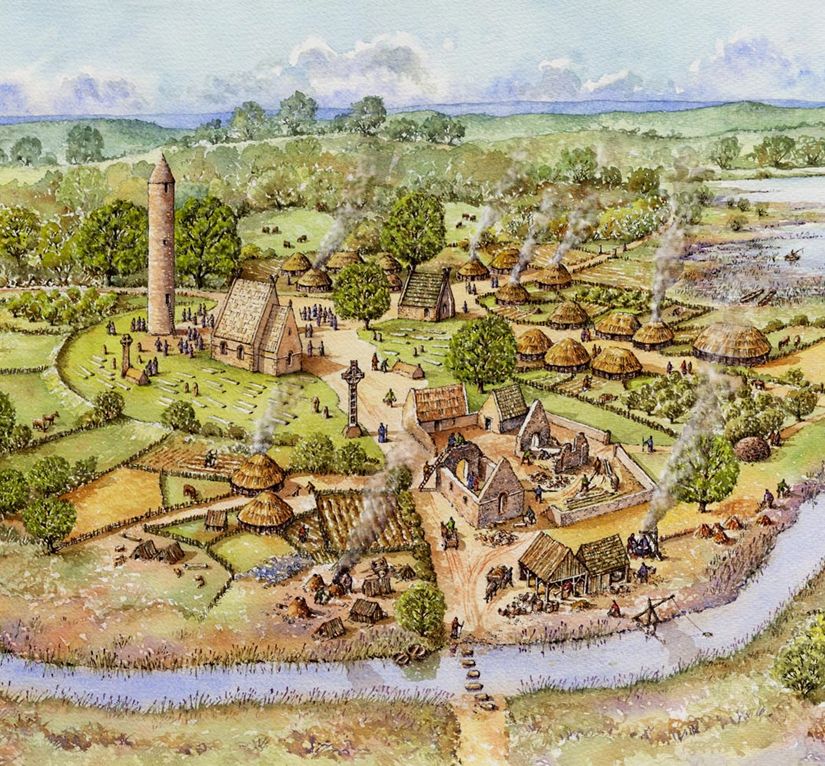

The HRE was sometimes called a Flickenteppich — “patchwork carpet”, due to its multiplicity of small, somewhat autonomous principalities.

At its peak, there were more than 300 Kleinstaaten (“little states”) in the empire, some covering no more than a few square miles.

At its peak, there were more than 300 Kleinstaaten (“little states”) in the empire, some covering no more than a few square miles.

This patchwork structure was akin to a federation, where some principalities were controlled either by church authorities (prince-bishops) or the emperor himself, while most were held by local princes who pledged fealty to the emperor.

A 1232 document explicitly calls German dukes domini terræ, or “owners of their lands”, making it clear that a level of independence existed apart from the emperor.

And this meant authority was very localized…

And this meant authority was very localized…

The emperor had little involvement at the local level — each principality was managed by its prince or bishop, creating a decentralized system where vassals looked to their lords for support or grievances rather than a far-off ruler.

The emperor’s role was primarily to maintain peace by 1) defending borders from external threats, and 2) settling inter-principality disputes through his court.

The princes were largely free to run their fiefs as they saw fit as long as the emperor’s interests were respected.

The princes were largely free to run their fiefs as they saw fit as long as the emperor’s interests were respected.

Another decentralized aspect of the empire was the selection of its ruler. Unlike other medieval monarchs, the Holy Roman Emperor was not hereditary, but elected.

A small body of powerful princes first elected the candidate and bestowed him the title “King of the Romans”.

A small body of powerful princes first elected the candidate and bestowed him the title “King of the Romans”.

According to the Golden Bull of 1356, seven “prince-electors” cast their votes: the archbishop of Mainz, the archbishop of Trier, the archbishop of Cologne, the king of Bohemia, the count palatine of the Rhine, the duke of Saxony and the margrave of Brandenburg.

Imperial candidates often negotiated with electors in a process called “electoral capitulation”.

Starting with Charles V in 1519, candidates swore to respect terms set by the electors, placing limits on the emperor’s authority — a sort of early “checks and balances”.

Starting with Charles V in 1519, candidates swore to respect terms set by the electors, placing limits on the emperor’s authority — a sort of early “checks and balances”.

To be formally named emperor, though, the candidate needed to be crowned by the Pope.

It often took years in between being elected king and officially becoming emperor. Ferdinand I , for example, waited a whopping 25 years before his coronation in 1556.

It often took years in between being elected king and officially becoming emperor. Ferdinand I , for example, waited a whopping 25 years before his coronation in 1556.

The HRE is perhaps the best example of subsidiarity implemented on a wide scale. Its implementation, even if unintended, was a huge factor in the empire’s longevity by creating a system of small, autonomous states held together by a common emperor.

Other political entities came and went, either succumbing to external threats or internal revolution. But the HRE remained a continuous empire for close to a millennium, surviving dynastic shifts and political changes.

Today, subsidiarity remains an important principle when evaluating governmental policies and programs.

A good litmus test for any new policy should be: does it follow the principle of subsidiarity?

A good litmus test for any new policy should be: does it follow the principle of subsidiarity?

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repost the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1853426154029436958

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh