1/ "For Aristotle, democracy is possible only within homogeneous ethnic groups, while despots reign over fragmented societies." This captures the spirit of Aristotle’s "Politics," written 2,300 years ago—wisdom America and the West must revisit in order to save our civilization!🧵

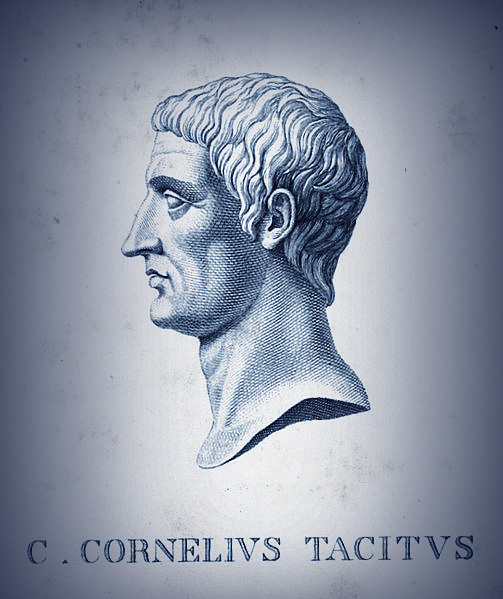

2/ The quote above comes from Guillaume Faye’s "Why We Fight," a powerful articulation often misattributed to Aristotle himself. Yet it captures the essence of Aristotle’s Politics ("Πολιτικά"), where he explores how democracy relies on a cohesive citizenry. For Aristotle, a stable society begins with a unified "ethnos" (ἔθνος)—a people whose distinct values and culture arise from a shared historical and evolutionary experience, shaped over generations. A culture, and thereby a nation, springs directly from its people and their vision for the future. Faye channels this conviction: "A multi-ethnic society is thus necessarily anti-democratic and chaotic, for it lacks philia, this profound, flesh-and-blood fraternity of citizens. Tyrants and despots divide and rule; they want the City divided by ethnic rivalries. The indispensable condition for ensuring a people's sovereignty accordingly resides in its unity. Ethnic chaos prevents all philia from developing."

Aristotle further elaborates on this concept in Politics, categorizing six types of government based on whether rulers pursue the common good or self-interest. When a single man governs justly, he embodies kingship ("basileia," βασιλεία), the noblest form of one-man rule; if he rules selfishly, he devolves into a tyrant ("tyrannos," τύραννος). Similarly, aristocracy ("aristokratia," ἀριστοκρατία) serves all under virtuous rulers but degenerates into oligarchy ("oligarchia," ὀλιγαρχία) when it serves the interests of the wealthy alone.

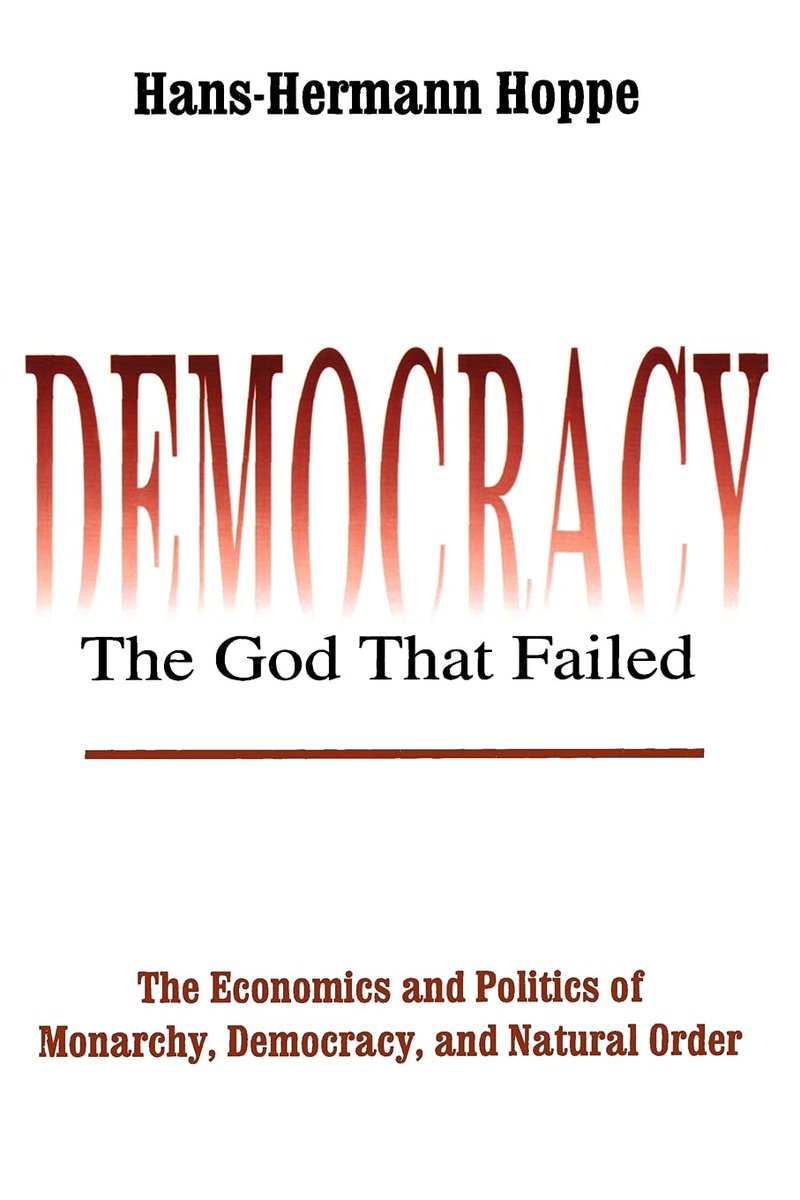

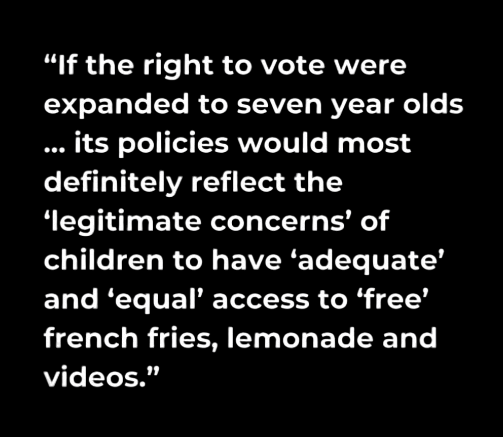

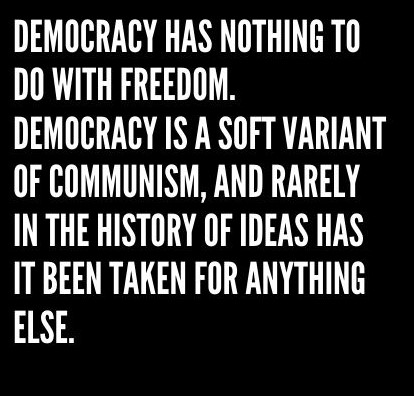

When the many rule for the common good, Aristotle calls this a polity ("politeia," πολιτεία), a mixed constitution and the most stable and desirable form of government. A polity balances democratic and oligarchic principles, drawing strength from a robust middle class that upholds justice ("dikaiosyne," δικαιοσύνη) and social harmony. In contrast, democracy ("demokratia," δημοκρατία) arises when the majority rules in its own interest, redistributing wealth at the expense of cohesion and encouraging factionalism.

Both democracy and oligarchy serve single classes, eroding the welfare of the "polis" ("πόλις," city-state). Democracy becomes a vehicle for the poor to exploit the wealthy, undermining justice and civic unity ("philia," φιλία), while oligarchy entrenches the power of the wealthy, deepening social divisions. Though livable, both forms compromise "areté" ("ἀρετή," virtue) and the common good. Their leaders often lack "phronesis" ("φρόνησις," practical wisdom), falling prey to factionalism and instability.

Thus, Aristotle envisions the polity as the highest attainable form—a government grounded in moderation ("metrios," μέτριος) and civic friendship ("philia," φιλία), harmonizing the virtues of both the many and the few to forge a just, enduring society. This unity relies on an ethnoculturally cohesive citizenry; as Faye argues, in a multi-ethnic society, philia disintegrates, allowing despots to exploit division. For Aristotle, as echoed by Faye, the polity demands a unified, ethnoculturally cohesive citizenry.

Aristotle further elaborates on this concept in Politics, categorizing six types of government based on whether rulers pursue the common good or self-interest. When a single man governs justly, he embodies kingship ("basileia," βασιλεία), the noblest form of one-man rule; if he rules selfishly, he devolves into a tyrant ("tyrannos," τύραννος). Similarly, aristocracy ("aristokratia," ἀριστοκρατία) serves all under virtuous rulers but degenerates into oligarchy ("oligarchia," ὀλιγαρχία) when it serves the interests of the wealthy alone.

When the many rule for the common good, Aristotle calls this a polity ("politeia," πολιτεία), a mixed constitution and the most stable and desirable form of government. A polity balances democratic and oligarchic principles, drawing strength from a robust middle class that upholds justice ("dikaiosyne," δικαιοσύνη) and social harmony. In contrast, democracy ("demokratia," δημοκρατία) arises when the majority rules in its own interest, redistributing wealth at the expense of cohesion and encouraging factionalism.

Both democracy and oligarchy serve single classes, eroding the welfare of the "polis" ("πόλις," city-state). Democracy becomes a vehicle for the poor to exploit the wealthy, undermining justice and civic unity ("philia," φιλία), while oligarchy entrenches the power of the wealthy, deepening social divisions. Though livable, both forms compromise "areté" ("ἀρετή," virtue) and the common good. Their leaders often lack "phronesis" ("φρόνησις," practical wisdom), falling prey to factionalism and instability.

Thus, Aristotle envisions the polity as the highest attainable form—a government grounded in moderation ("metrios," μέτριος) and civic friendship ("philia," φιλία), harmonizing the virtues of both the many and the few to forge a just, enduring society. This unity relies on an ethnoculturally cohesive citizenry; as Faye argues, in a multi-ethnic society, philia disintegrates, allowing despots to exploit division. For Aristotle, as echoed by Faye, the polity demands a unified, ethnoculturally cohesive citizenry.

3/ Aristotle’s concept of the polity ("politeia," πολιτεία) represents an ideal balance, integrating democratic and oligarchic elements to forge a stable constitution that serves the entire community. In Politics, Aristotle presents the polity as the path of moderation, countering extremes to foster a society free from class antagonism and factionalism.

Central to the polity is moderation ("metrios," μέτριος), which avoids the pitfalls of unchecked democracy (where the majority rules for itself) and oligarchy (where the few do likewise). This moderation cultivates philia (φιλία), or civic friendship—a unity that transcends laws, drawing strength from shared culture and ethnicity. In a polity, this philia binds citizens through a shared identity, forming a cohesive body politic rather than a field of competing factions.

Aristotle’s ideal polity is grounded in "areté" (ἀρετή, virtue) and "logos" (λόγος, reason), with a "telos" (τέλος, purpose) aimed at achieving human flourishing. A large, virtuous middle class acts as a stabilizing force against the extremes of wealth and poverty, safeguarding justice ("dikaiosyne," δικαιοσύνη) and ensuring that governance aligns with the interests of all.

For Aristotle, the polity stands as the most "kalos" (καλός, noble) form of government, reflecting the unity and virtue of its people. Its stability depends on underlying ethnocultural coherence; a society divided along ethnic lines lacks the philia essential for a polity to function effectively. Without unity, factionalism reigns, leaving power to those who exploit division for control.

Central to the polity is moderation ("metrios," μέτριος), which avoids the pitfalls of unchecked democracy (where the majority rules for itself) and oligarchy (where the few do likewise). This moderation cultivates philia (φιλία), or civic friendship—a unity that transcends laws, drawing strength from shared culture and ethnicity. In a polity, this philia binds citizens through a shared identity, forming a cohesive body politic rather than a field of competing factions.

Aristotle’s ideal polity is grounded in "areté" (ἀρετή, virtue) and "logos" (λόγος, reason), with a "telos" (τέλος, purpose) aimed at achieving human flourishing. A large, virtuous middle class acts as a stabilizing force against the extremes of wealth and poverty, safeguarding justice ("dikaiosyne," δικαιοσύνη) and ensuring that governance aligns with the interests of all.

For Aristotle, the polity stands as the most "kalos" (καλός, noble) form of government, reflecting the unity and virtue of its people. Its stability depends on underlying ethnocultural coherence; a society divided along ethnic lines lacks the philia essential for a polity to function effectively. Without unity, factionalism reigns, leaving power to those who exploit division for control.

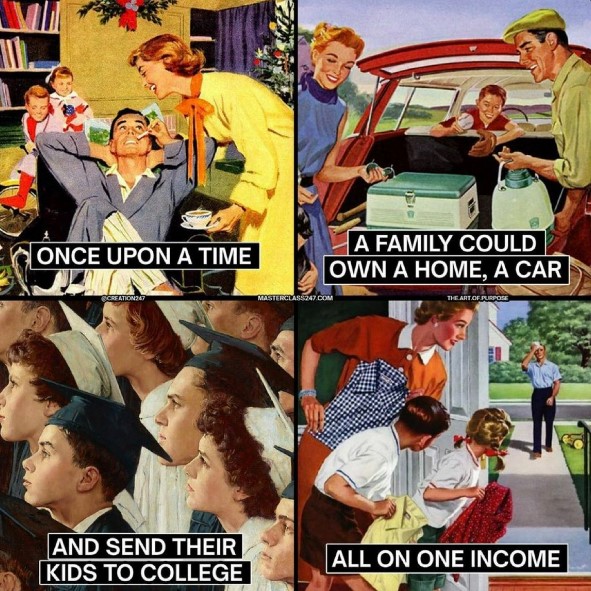

4/ Applying Aristotle’s concept of a polity to modern America (and the West more broadly) underscores the need for governance rooted in balance, moderation, and civic unity—qualities sorely absent in a demographically Balkanized democracy, found primarily in the Western world (with some exceptions like Singapore and a few other polities).

A polity-centered government resists the whims of competing, volatile, heterogeneous majorities, maintaining a stable middle ground where different economic classes of the same ethnos contribute to the common good. Unlike mass democracy, which shifts with populist demands, a polity relies on a strong, virtuous middle class to provide balanced representation, insulating governance from extremes.

Moreover, an American polity would demand a shared cultural and ethnic foundation—an ethnocultural demographic homogeneity. As Faye notes, Aristotle argued that democracy can only thrive within homogeneous groups; where society fragments, philia fails, and unity disintegrates. Multi-ethnic societies inevitably collapse into factionalism, with each group prioritizing its own interests over the common good, transforming governance into a demographically Balkanized spoils system—a zero-sum game where each faction strives for its own gain. This erosion of philia leaves society vulnerable to despots who exploit division for power. For America, a true polity could succeed only if it rested on a shared ethnocultural identity that fosters solidarity.

In advocating for a polity, we argue for a system that prioritizes the common good, transcending economic and ideological divides, and grounded in cultural and ethnic bonds. Such a system would cultivate "philia," reinforcing the civic friendship essential to just governance. Only through this unity can a polity withstand divisive forces and guide a nation toward genuine common welfare.

A polity-centered government resists the whims of competing, volatile, heterogeneous majorities, maintaining a stable middle ground where different economic classes of the same ethnos contribute to the common good. Unlike mass democracy, which shifts with populist demands, a polity relies on a strong, virtuous middle class to provide balanced representation, insulating governance from extremes.

Moreover, an American polity would demand a shared cultural and ethnic foundation—an ethnocultural demographic homogeneity. As Faye notes, Aristotle argued that democracy can only thrive within homogeneous groups; where society fragments, philia fails, and unity disintegrates. Multi-ethnic societies inevitably collapse into factionalism, with each group prioritizing its own interests over the common good, transforming governance into a demographically Balkanized spoils system—a zero-sum game where each faction strives for its own gain. This erosion of philia leaves society vulnerable to despots who exploit division for power. For America, a true polity could succeed only if it rested on a shared ethnocultural identity that fosters solidarity.

In advocating for a polity, we argue for a system that prioritizes the common good, transcending economic and ideological divides, and grounded in cultural and ethnic bonds. Such a system would cultivate "philia," reinforcing the civic friendship essential to just governance. Only through this unity can a polity withstand divisive forces and guide a nation toward genuine common welfare.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh