APOLLO'S $4.5 BILLION MISSED PROFITS - CARVANA

A few days ago, the FT published an interesting article about the 2023 Carvana out-of-court restructuring where Apollo took a $1.3bn haircut on $5.6bn of unsecured junk bonds.

The article ends with a provoking sentence: "Apollo and others should rue that they did not demand equity warrants". If you are wondering how much money Apollo left on the table, you are in the right spot.

Based on my math -> $4.481Bn

1) Warrants in Restructuring

2) Assumptions of the Apollo Missed Warrants

3) Apollo Implied Value Equation

4) Current Value of Warrants

5) Sensitivity and Conclusion

A Thread 🧵

A few days ago, the FT published an interesting article about the 2023 Carvana out-of-court restructuring where Apollo took a $1.3bn haircut on $5.6bn of unsecured junk bonds.

The article ends with a provoking sentence: "Apollo and others should rue that they did not demand equity warrants". If you are wondering how much money Apollo left on the table, you are in the right spot.

Based on my math -> $4.481Bn

1) Warrants in Restructuring

2) Assumptions of the Apollo Missed Warrants

3) Apollo Implied Value Equation

4) Current Value of Warrants

5) Sensitivity and Conclusion

A Thread 🧵

1) Warrants in Restructuring

In order to understand this thread, we need to understand the basics first.

In the beautiful world of restructuring and corporate reorganization, there are times when the value of the business is not enough to cover the claims of all debt holders. As a result, companies go to their creditors asking to renegotiate their claims in order to stay alive and maximize everyone's value in the long term.

But what if the company has nothing to offer? A possible solution is issuing warrants (security that gives the holder the right to buy or sell a specific number of shares of a company at a specific price, called the strike price before the warrant expires).

Let's say a company is trying to create a fair and equitable plan for all creditors, but the second lien creditors demand more. The issue is that there is no more debt capacity or equity to give. A possible solution is giving them (completely made-up numbers) " five-year new warrants issued to second lien lenders which would entitle them to purchase up to 12.5% of reorganized equity at a strike price equal to the value of reorganized equity".

We therefore now understand what the sentence "Apollo and others should rue that they did not demand equity warrants" is trying to tell us: Apollo wished they had negotiated some of these warrants, something that often happens in restructuring situations.

In order to understand this thread, we need to understand the basics first.

In the beautiful world of restructuring and corporate reorganization, there are times when the value of the business is not enough to cover the claims of all debt holders. As a result, companies go to their creditors asking to renegotiate their claims in order to stay alive and maximize everyone's value in the long term.

But what if the company has nothing to offer? A possible solution is issuing warrants (security that gives the holder the right to buy or sell a specific number of shares of a company at a specific price, called the strike price before the warrant expires).

Let's say a company is trying to create a fair and equitable plan for all creditors, but the second lien creditors demand more. The issue is that there is no more debt capacity or equity to give. A possible solution is giving them (completely made-up numbers) " five-year new warrants issued to second lien lenders which would entitle them to purchase up to 12.5% of reorganized equity at a strike price equal to the value of reorganized equity".

We therefore now understand what the sentence "Apollo and others should rue that they did not demand equity warrants" is trying to tell us: Apollo wished they had negotiated some of these warrants, something that often happens in restructuring situations.

2) Assumptions of Missed Warrants

We now understand the dynamics, but why is missing out on the warrants so tragic here? Because the stock price has increased over 10x since the deal was signed so a lot of money could have been made.

How much money? Let's try to figure it out.

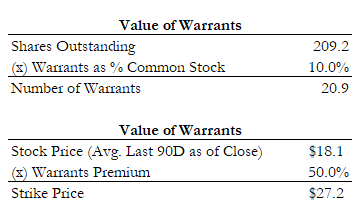

We need to make a few key assumptions here. Firstly, how much Carvana equity Apollo could have demanded? I believe 10% is a fair assumption (in the next tweet and the last one will show why I think this is a fair assumption).

Once we agree on how many warrants as % Total to issue, the next step is to calculate how many warrants are issued which we can calculate as Share Count * % Equity Issued = 21MM Warrants

The next key question to calculate profit would be to know the strike price of these contracts. This is the second key assumption we need to make (here I could be very wrong). It is hard to get a sense as most of the figures we know are from in-court situations while here we are out-of-court and therefore the equity is still fluctuating in value every day (differently from the example above "strike price equal to the value of reorganized equity").

I would doubt that Carvana would have ever given out warrants without premium (which would essentially mean diluting the equity by 10% right away).

For our calculation, let's use a 50% premium. Again, this might be wrong, but as the sensitivity analysis will show us, this assumption does not really matter. More on this later.

The last thing we need to understand is the price this premium will be applied to. This is usually not tricky but here we are in a unique scenario as the stock was seeing huge volatility.

The deal was announced on July 19, 2023 so for our calculation I took the last 90 days' average which comes out to $18.1 / share.

Putting these two things together, we can calculate the strike of the warrants = $27.2

Please note: the above assumptions are (obviously) solely my own.

We now understand the dynamics, but why is missing out on the warrants so tragic here? Because the stock price has increased over 10x since the deal was signed so a lot of money could have been made.

How much money? Let's try to figure it out.

We need to make a few key assumptions here. Firstly, how much Carvana equity Apollo could have demanded? I believe 10% is a fair assumption (in the next tweet and the last one will show why I think this is a fair assumption).

Once we agree on how many warrants as % Total to issue, the next step is to calculate how many warrants are issued which we can calculate as Share Count * % Equity Issued = 21MM Warrants

The next key question to calculate profit would be to know the strike price of these contracts. This is the second key assumption we need to make (here I could be very wrong). It is hard to get a sense as most of the figures we know are from in-court situations while here we are out-of-court and therefore the equity is still fluctuating in value every day (differently from the example above "strike price equal to the value of reorganized equity").

I would doubt that Carvana would have ever given out warrants without premium (which would essentially mean diluting the equity by 10% right away).

For our calculation, let's use a 50% premium. Again, this might be wrong, but as the sensitivity analysis will show us, this assumption does not really matter. More on this later.

The last thing we need to understand is the price this premium will be applied to. This is usually not tricky but here we are in a unique scenario as the stock was seeing huge volatility.

The deal was announced on July 19, 2023 so for our calculation I took the last 90 days' average which comes out to $18.1 / share.

Putting these two things together, we can calculate the strike of the warrants = $27.2

Please note: the above assumptions are (obviously) solely my own.

3) Apollo Implied Value Equation

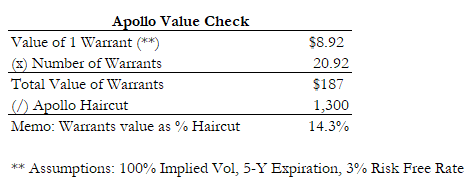

Before moving to calculate the value of the warrants today, I thought it would be useful to sense-check if we are on the right path (i.e. how much were these warrants worth at issuance compared to how much debt was written off).

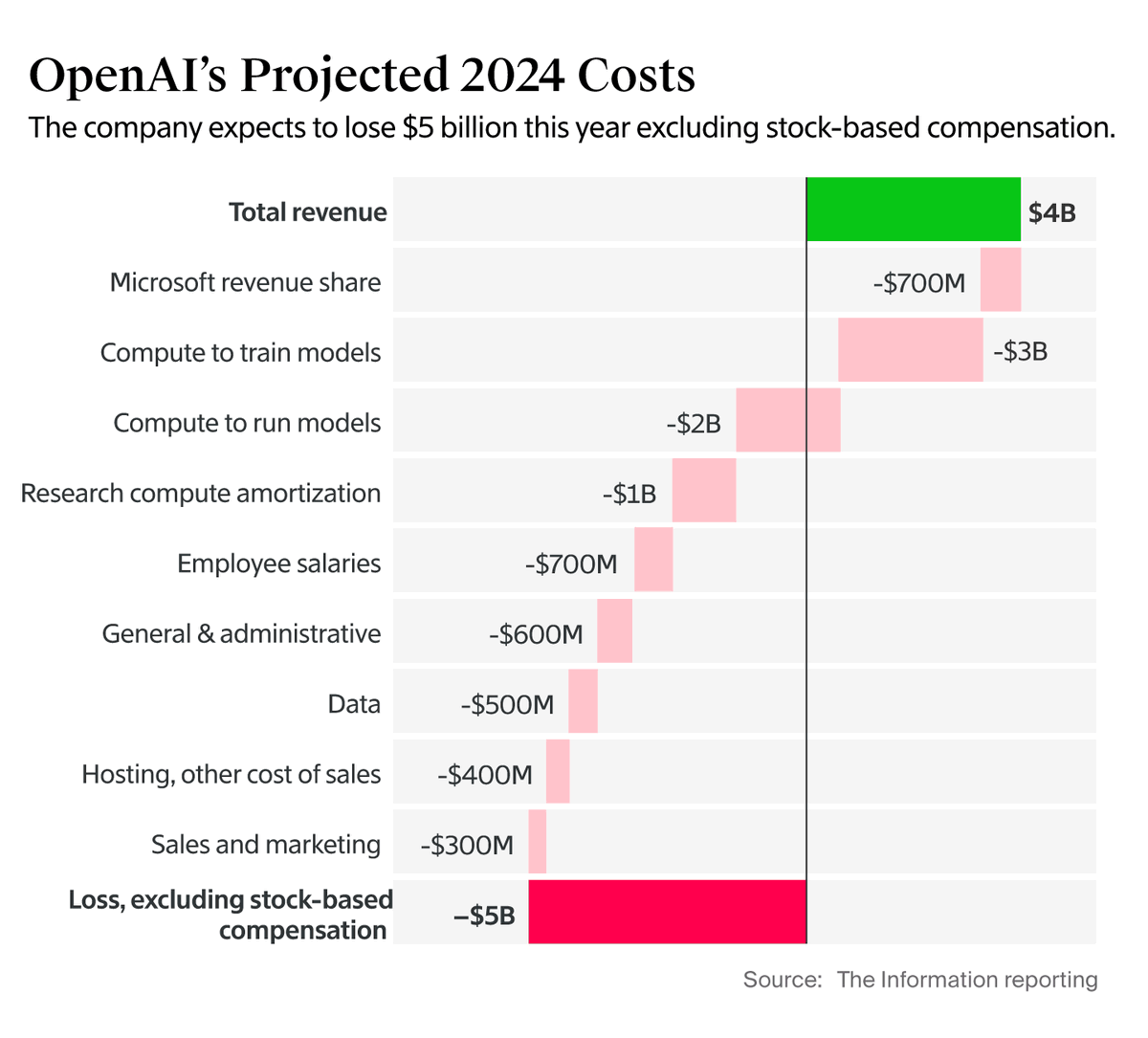

First, we need to calculate the value of each warrant and then multiply it by how many were issued. I downloaded the beautiful Damodaran option price calculator and used the following assumptions (5 Year warrants duration, 100% implied vol for the stock, and 3% Risk Free Rate). With the stock price and strike price calculated above, I arrived at a value of $8.92 / warrant. This multiplied by the 21MM warrants issued gets $187MM of value issued.

Considering Apollo agreed to cut $1.3Bn of Debt, getting 14% of the value back through warrants seems reasonable.

Moving right along.

Before moving to calculate the value of the warrants today, I thought it would be useful to sense-check if we are on the right path (i.e. how much were these warrants worth at issuance compared to how much debt was written off).

First, we need to calculate the value of each warrant and then multiply it by how many were issued. I downloaded the beautiful Damodaran option price calculator and used the following assumptions (5 Year warrants duration, 100% implied vol for the stock, and 3% Risk Free Rate). With the stock price and strike price calculated above, I arrived at a value of $8.92 / warrant. This multiplied by the 21MM warrants issued gets $187MM of value issued.

Considering Apollo agreed to cut $1.3Bn of Debt, getting 14% of the value back through warrants seems reasonable.

Moving right along.

4) Current Value of Warrants

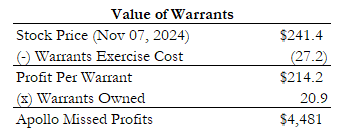

Let's get to the meat. How much did Apollo leave on the table?

Today, Carvana stock closed at $241. Let's assume Apollo owned these warrants and wanted to exit their position. They would have the right to buy 21MM shares at the strike price ($27.2) and then they would be able to sell them on the open market (let's assume no price impact despite a significant dilution for simplicity).

Overall, this would net $4.5Bn in Profits (remember there is no cost base here).

Yes, a lot of dollars.

Let's get to the meat. How much did Apollo leave on the table?

Today, Carvana stock closed at $241. Let's assume Apollo owned these warrants and wanted to exit their position. They would have the right to buy 21MM shares at the strike price ($27.2) and then they would be able to sell them on the open market (let's assume no price impact despite a significant dilution for simplicity).

Overall, this would net $4.5Bn in Profits (remember there is no cost base here).

Yes, a lot of dollars.

5) Sensitivity and Conclusion

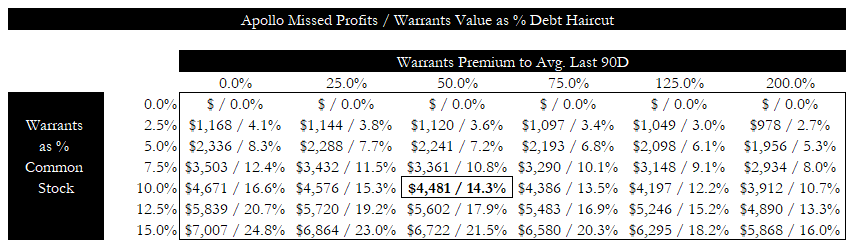

This is my favorite part of this analysis. We are sensitizing two assumptions, warrant premium (or strike price) and how many warrants we issuing. Three things stand out:

1) As expected, how many warrants we are issuing is really all that matters here. If you think Apollo would have never got 10% of the equity but much less, you can easily see how many dollars they left on the table (still in the billions range).

2) The warrant premium (or strike price) does not really move the needle. The stock ended up being so much higher than the strike price that the dollar impact is marginal. In general, creditors will fight for a low premium so the chances of these warrants having intrinsic value are higher.

3) This said, the higher the warrant premium at issuance, the lower the value of the warrants which makes the warrant value as % of the debt haircut lower.

This is my favorite part of this analysis. We are sensitizing two assumptions, warrant premium (or strike price) and how many warrants we issuing. Three things stand out:

1) As expected, how many warrants we are issuing is really all that matters here. If you think Apollo would have never got 10% of the equity but much less, you can easily see how many dollars they left on the table (still in the billions range).

2) The warrant premium (or strike price) does not really move the needle. The stock ended up being so much higher than the strike price that the dollar impact is marginal. In general, creditors will fight for a low premium so the chances of these warrants having intrinsic value are higher.

3) This said, the higher the warrant premium at issuance, the lower the value of the warrants which makes the warrant value as % of the debt haircut lower.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh