IB RX - MF PE - HF Investor sharing lessons mostly on Restructuring and Distressed Debt - Check out Pari Passu! DMs are open! - @9finHQ fan

10 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

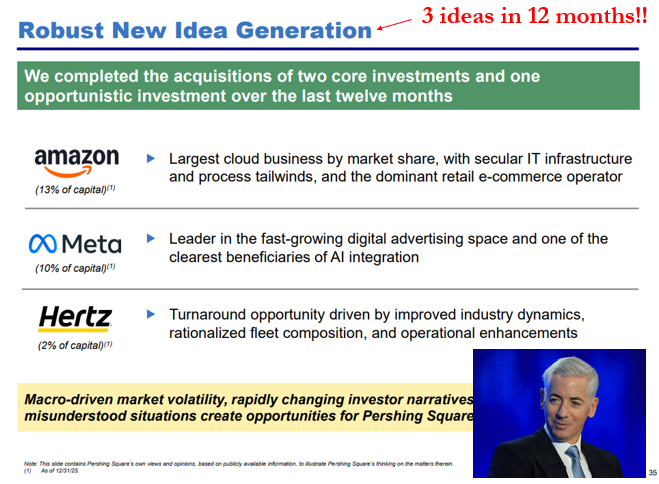

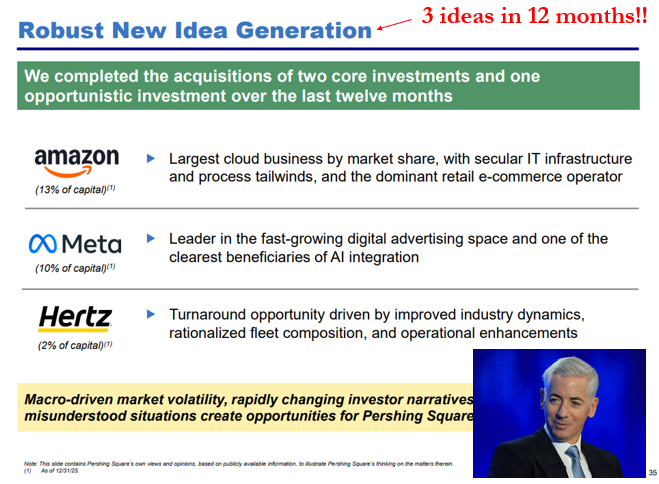

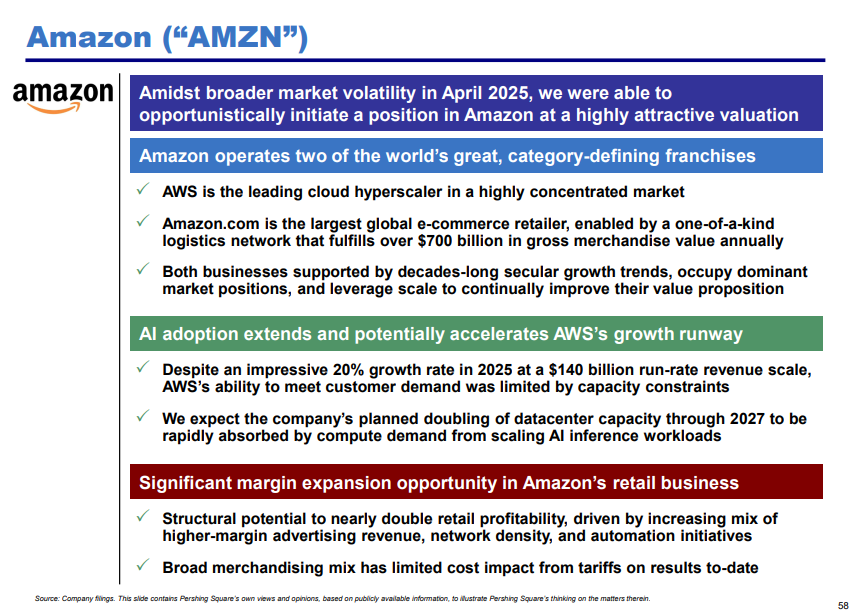

2/n Amazon Thesis

2/n Amazon Thesis

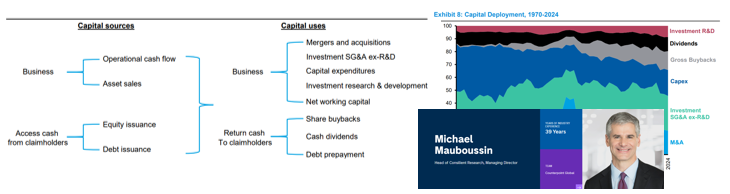

1) What Every Great Business Has in Common

1) What Every Great Business Has in Common

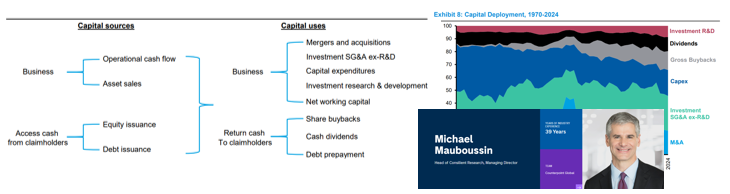

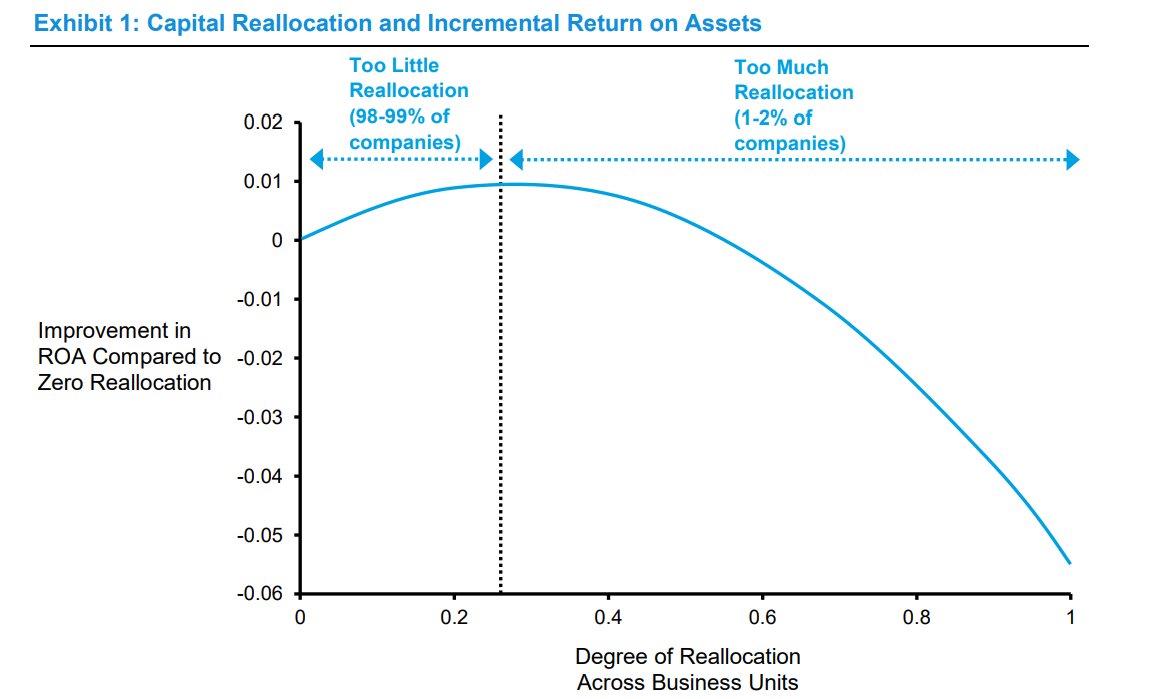

1) Lack of Capital Reallocation

1) Lack of Capital Reallocation

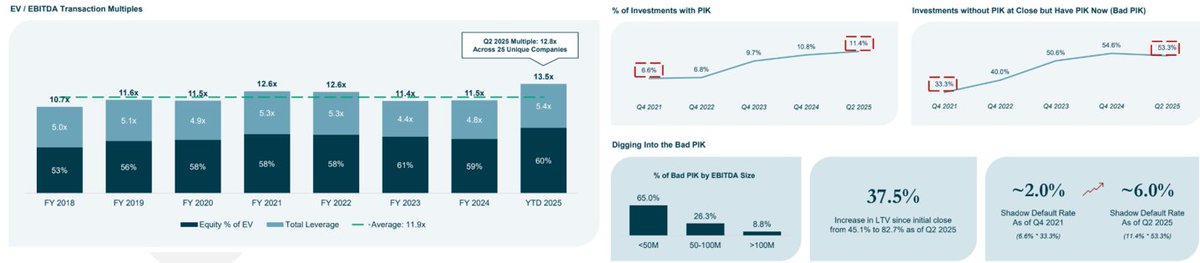

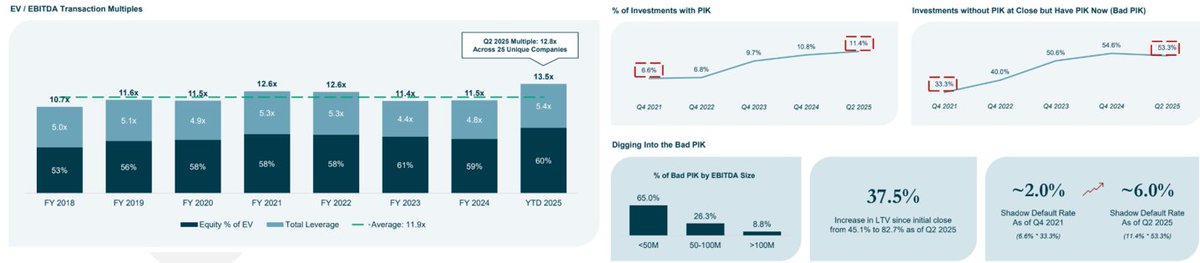

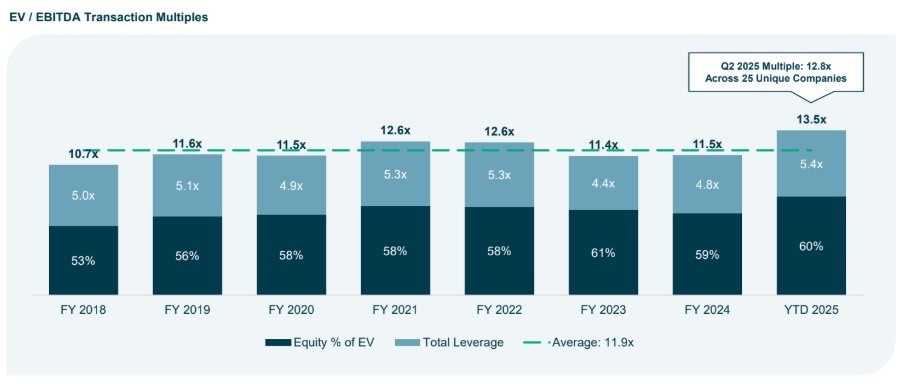

1) EV / EBITDA Transaction Multiples

1) EV / EBITDA Transaction Multiples

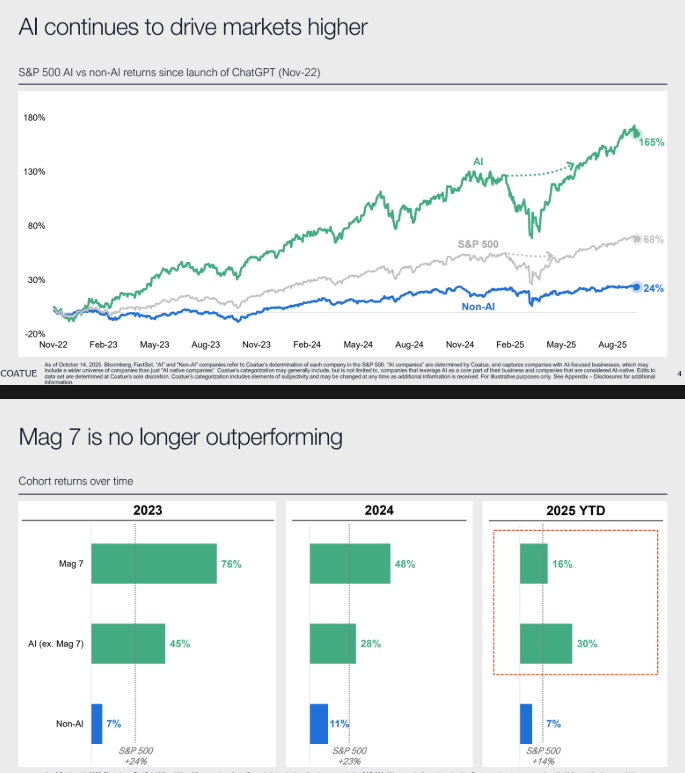

1) AI continues to drive markets higher but...

1) AI continues to drive markets higher but...

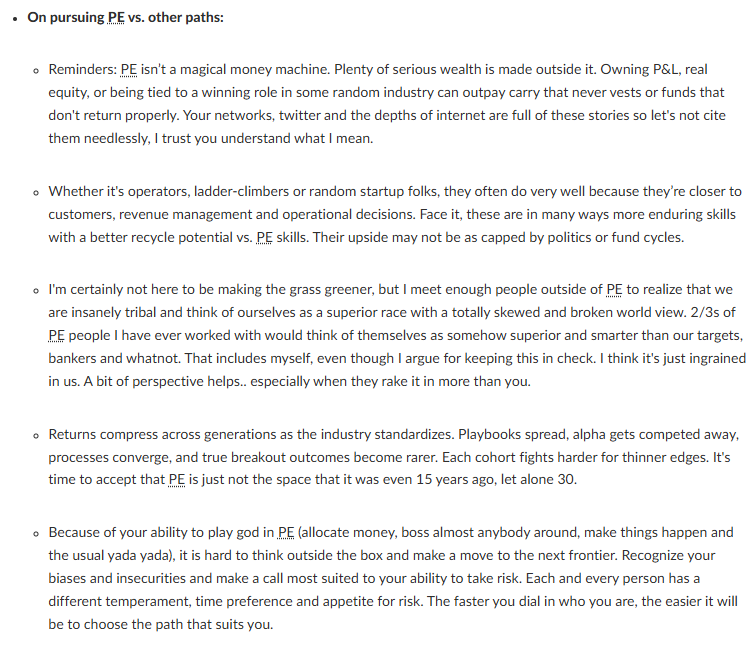

1) On pursuing PE vs. other paths

1) On pursuing PE vs. other paths

1) Factoring Basics

1) Factoring Basics

1) Good Companies, Bad Capital

1) Good Companies, Bad Capital

1) Data Center and Vertiv Overview

1) Data Center and Vertiv Overview

1) Pepsi Today

1) Pepsi Today

1) Where I was right

1) Where I was right

1) Betting on CityMD

1) Betting on CityMD

1) Option 1: Subsidiary Structuring

1) Option 1: Subsidiary Structuring

Insurance 101

Insurance 101

1) Private Wealth: Overview

1) Private Wealth: Overview

1/ Tech Trends - higher returns but more volatility and drawdowns

1/ Tech Trends - higher returns but more volatility and drawdowns

1) Rise of “Distressed-by-Accident” Cases

1) Rise of “Distressed-by-Accident” Cases

1. From Hedge‑Fund Desk to $800bn Platform

1. From Hedge‑Fund Desk to $800bn Platform