LTV:CAC has become a somewhat controversial metric in DTC. Commonly used in SaaS, LTV:CAC in consumer brands is hotly debated as to whether or not this SHOULD apply

So here's a dedicated thread DEBUNKING THE MYTHS and explaining EVERYTHING you need to know about LTV:CAC 👇👇

So here's a dedicated thread DEBUNKING THE MYTHS and explaining EVERYTHING you need to know about LTV:CAC 👇👇

1/ Definition

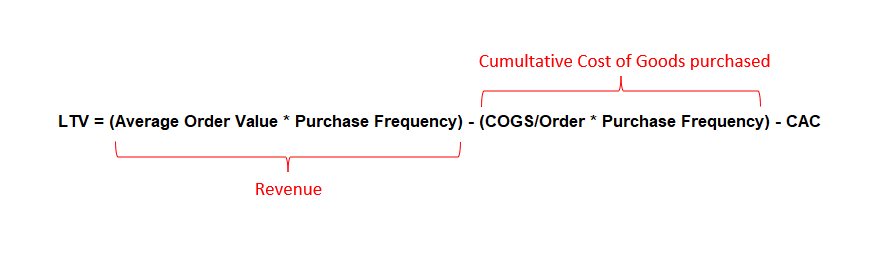

Ok, the definition is the root of all problems. Often, people look at LTV as the lifetime REVENUE per customer

That's fine, its a worthwhile thing to track

BUT; LTV in the context of LTV:CAC is the LIFETIME CONTRIBUTION per customer, not revenue

Ok, the definition is the root of all problems. Often, people look at LTV as the lifetime REVENUE per customer

That's fine, its a worthwhile thing to track

BUT; LTV in the context of LTV:CAC is the LIFETIME CONTRIBUTION per customer, not revenue

2/ Contribution Margin

So lets just get this out of the way. Contribution Margin in ecommerce is DIFFERENT than CM in retail.

I am SICK of seeing 'CM1' & 'CM 2' etc for profit after product costs & then after shipping

CM is profit after ALL variable expenses incl logistics

So lets just get this out of the way. Contribution Margin in ecommerce is DIFFERENT than CM in retail.

I am SICK of seeing 'CM1' & 'CM 2' etc for profit after product costs & then after shipping

CM is profit after ALL variable expenses incl logistics

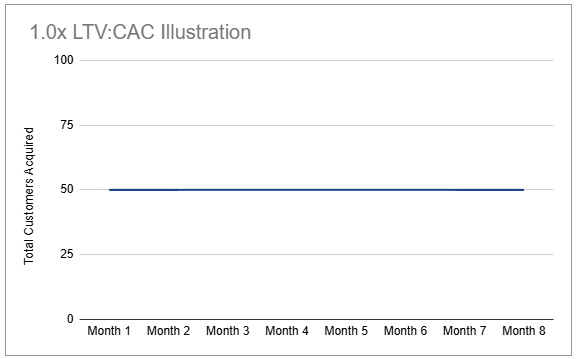

1/ 1.0 LTV:CAC

If contribution per customer divided by CAC = 1.0, this means your unit economics are breakeven. Include any level of opex and you're burning cash. You can't grow without burning incremental cash, and you're flat

If contribution per customer divided by CAC = 1.0, this means your unit economics are breakeven. Include any level of opex and you're burning cash. You can't grow without burning incremental cash, and you're flat

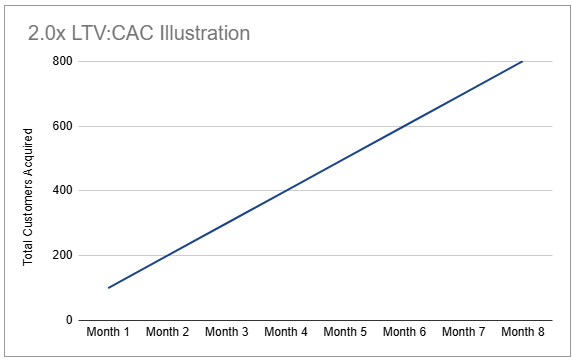

3/ 2.0x LTV:CAC

If Contribution per customer/CAC = 2.0, you pay back CAC and have enough left to acquire another customer. Great work - you now get to reinvest in getting 1 new customer for every 1 acquired, driving 1:1, or linear, growth:

If Contribution per customer/CAC = 2.0, you pay back CAC and have enough left to acquire another customer. Great work - you now get to reinvest in getting 1 new customer for every 1 acquired, driving 1:1, or linear, growth:

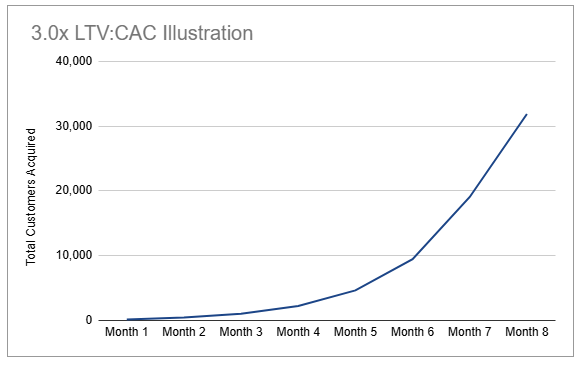

4/ 3.0 LTV:CAC

This is where LTV:CAC becomes a clearly useful metric, and why 3.0x is the gold standard in venture capital.

When contribution dollars/CAC = 3.0x, you have acquired a customer, say for 1 dollar, and now you have TWO dollars left over generated by ONE customer

This is where LTV:CAC becomes a clearly useful metric, and why 3.0x is the gold standard in venture capital.

When contribution dollars/CAC = 3.0x, you have acquired a customer, say for 1 dollar, and now you have TWO dollars left over generated by ONE customer

5/

Now, everyone ONE customer you acquire creates enough profit to acquire TWO more customers.

1 Customer = acquire +2 more

+2 more = acquire +4more

+4 more = acquire +8more

This compounds into exponential growth, and your curve looks like a hockey stick

Now, everyone ONE customer you acquire creates enough profit to acquire TWO more customers.

1 Customer = acquire +2 more

+2 more = acquire +4more

+4 more = acquire +8more

This compounds into exponential growth, and your curve looks like a hockey stick

6/ THE PROBLEM

The key to LTV:CAC is understanding the idea that you're creating enough PROFIT to acquire +2more customers for everyone customer acquired

If ur looking at LTV on a sales basis, and you have a 3.0, if your CM ratio per order is even 50%, you are actually a 2.0

The key to LTV:CAC is understanding the idea that you're creating enough PROFIT to acquire +2more customers for everyone customer acquired

If ur looking at LTV on a sales basis, and you have a 3.0, if your CM ratio per order is even 50%, you are actually a 2.0

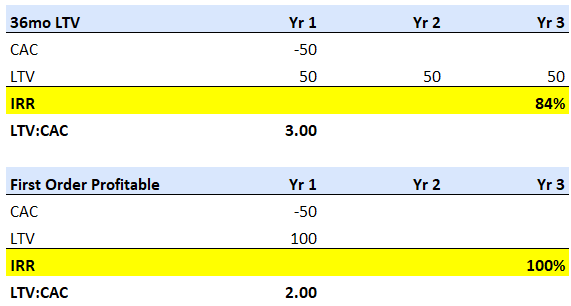

7/ But here's the kicker

Time matters. If you have a beautiful 3.0 LTV:CAC but it takes 36 months to realize the CAC, you are actually WORSE OFF from an IRR perspective than someone with a 2.0 on first purchase

In other words, too long of a payback period negates this

Time matters. If you have a beautiful 3.0 LTV:CAC but it takes 36 months to realize the CAC, you are actually WORSE OFF from an IRR perspective than someone with a 2.0 on first purchase

In other words, too long of a payback period negates this

8/ When you should use LTV:CAC

When you KNOW your unit economics. This is a data problem, not an intelligence or awareness problem. In other words, you don't know your unit economics on amazon without having built some tool to help you. You do know cohort analytics from shopify

When you KNOW your unit economics. This is a data problem, not an intelligence or awareness problem. In other words, you don't know your unit economics on amazon without having built some tool to help you. You do know cohort analytics from shopify

9/ Common LTV:CAC pitfalls

1. Looking at revenue LTV exclusively

2. Using gross sales in LTV

3. Not having insights into amazon cohorts

4. Not including ALL VARIABLE EXPENSES (3PL)

5. Not performing accruals during cohort analysis (i.e., crediting returns to proper customers)

1. Looking at revenue LTV exclusively

2. Using gross sales in LTV

3. Not having insights into amazon cohorts

4. Not including ALL VARIABLE EXPENSES (3PL)

5. Not performing accruals during cohort analysis (i.e., crediting returns to proper customers)

9/ In summary

LTV:CAC is a fine, maybe even good metric to track. Oftentimes mistakes around the calculations and thought processes are made, which make it a VERY dangerous north star

It works, but you have to know what you're doing and take it in context with every other KPI

LTV:CAC is a fine, maybe even good metric to track. Oftentimes mistakes around the calculations and thought processes are made, which make it a VERY dangerous north star

It works, but you have to know what you're doing and take it in context with every other KPI

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh