“Reviewing Hadith against the Qur’an”: A Disputed Principle in Early Islam 🧵

When Shāfiʿī (d. 204) quotes numerous Prophetic reports to support his position in a debate with Shaybānī (d. 179), the latter rejects all of the reports citing a Hadith which has the Prophet state:

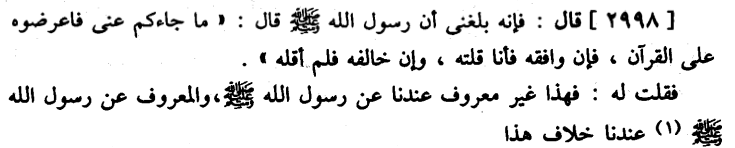

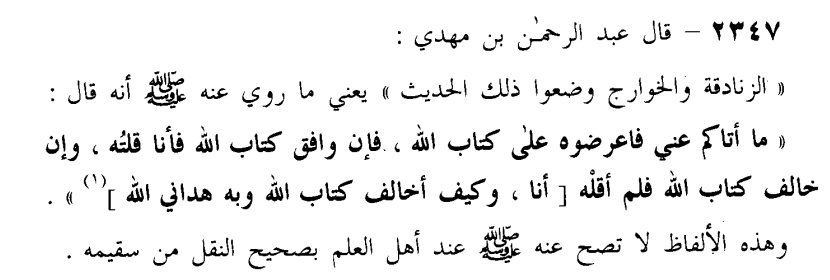

When Shāfiʿī (d. 204) quotes numerous Prophetic reports to support his position in a debate with Shaybānī (d. 179), the latter rejects all of the reports citing a Hadith which has the Prophet state:

“Whatever comes to you on my authority then review it against the Qur’an, so if it agrees with it (i.e. the Qur’an) then I said it, and if it opposes it than I never said it”

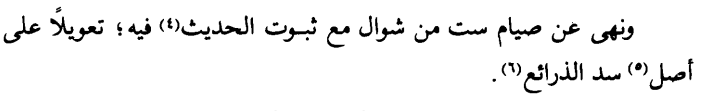

Shāfiʿī, for his part, vehemently rejects this Hadith and counters with a Hadith of his own which somehow predicts the emergence of an attitude exactly like Shaybānī’s.

The Prophet supposedly states: “I should not come across one of you reclining in his seat and when an injunction of mine, be it something I commanded or prohibited, is relayed to him - remarks: ‘We don’t know (about this). What we find in the Book of Allah we follow!’”

Shāfiʿī’s Hadith would end up in 3 of the 6 canonical works of Sunni Hadith as opposed to Shaybānī’s Hadith which is nowhere to be found therein, having been consigned to the heap of rejected reports.

It is clear that the Ahl al-Ḥadīth were threatened by any notion of giving the Qur’an an upper-hand over Prophetic reports, something diametrically opposed to their epistemology, which can be best summed up by the dictum attributed to Yaḥyā b. Abī Kathīr (d. c. 130):

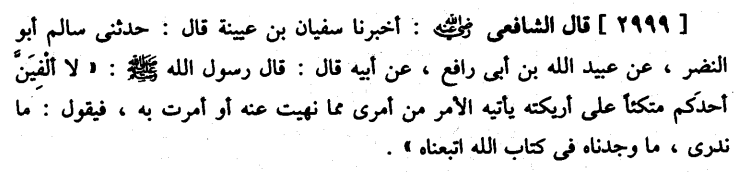

In fact, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī (d. 198) would go so far as to consider all those reports which require a Hadith to first be reviewed against the Qur’an before acceptance to be a fabrication of the damned zanādiqa (heretics) accused of looking for a way to reject reports.

But is this where Shaybānī got his Hadith? From heretics?

Shaybānī does not give us a chain for the Hadith he cites, but Abū Yūsuf (d. 182), Shaybānī’s colleague and fellow student of Abū Ḥanīfa, quotes a Hadith with similar meaning in his treatise authored to refute al-Awzāʿī (d. 157).

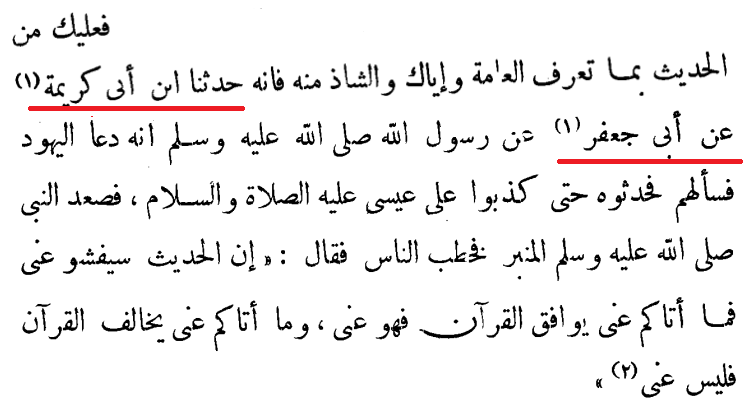

Ibn Abī Karīma narrates from Abī Jaʿfar al-Bāqir who has the Messenger of Allah ascending the pulpit after hearing some Jews recount falsities about Jesus and making the following speech:

“A lot of Hadith will be spread about me. So whatever comes to you on my authority which agrees with the Qur’an then it is from me, and whatever comes to you on my authority that opposes the Qur’an then it is not from me!”

Could Shaybānī have got his Hadith from Abū Yūsuf from Ibn Abī Karīma from al-Bāqir as opposed to some random heretic?

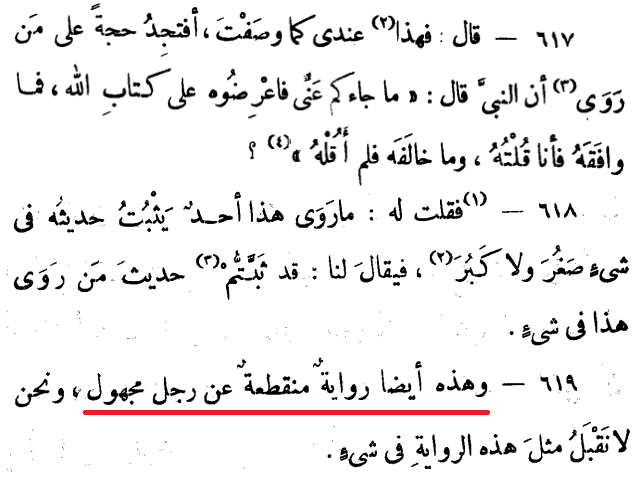

This seems to be confirmed by Shāfiʿī who quotes Shaybānī’s Hadith verbatim in his Risāla and then attacks its chain (without naming its narrators explicitly) as follows:

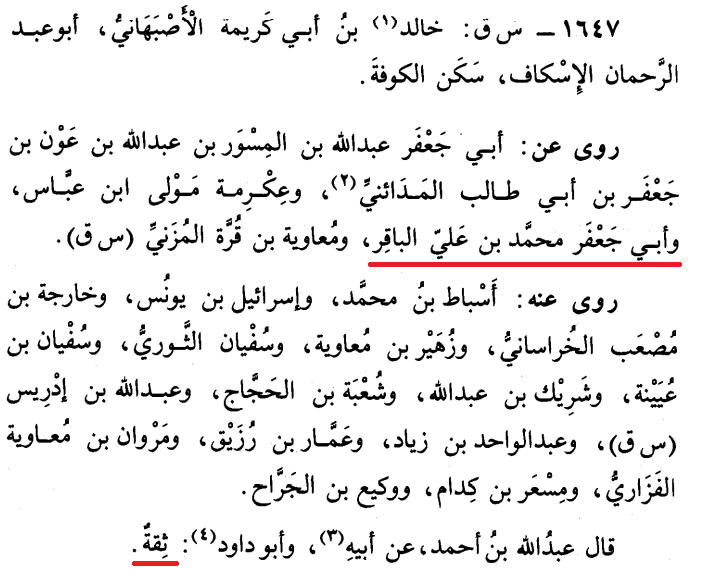

(A) Its narrator (= Ibn Abī Karīma) is majhūl (unknown).

(B) The report is munqatiʿ (disconnected) since we do not know from whom al-Bāqir, who is a tābiʿī, got it from.

(B) The report is munqatiʿ (disconnected) since we do not know from whom al-Bāqir, who is a tābiʿī, got it from.

But Shāfiʿī is misinformed about (A), for the Hadith critics of the next generation, like Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal (d. 241) and Yaḥyā b. Maʿīn (d. 233), would come to strengthen Ibn Abī Karīma.

As for (B), then it is common for al-Bāqir to report directly in this way from the Messenger of Allah in both the Sunni and Imami Hadith corpus, something the Imamis attribute to his self-perception as an ultimate authority ...

... who did not need to attribute his knowledge to random companions, having received it as part of a privileged family tradition.

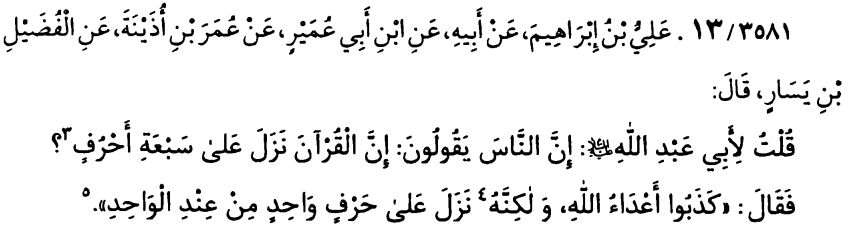

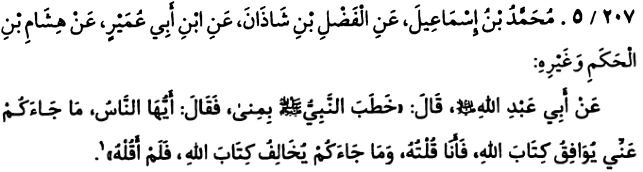

The historical link of this Hadith to al-Bāqir is further strengthened when we find a similar content attributed to his son Jaʿfar in the Imami Hadith corpus.

The Prophet gave a speech at Mina saying: “O people, whatever comes to you on my authority agreeing with the Book of Allah then I said it, and whatever comes to you opposing the Book of Allah then I did not say it”

This, then, was one important but disputed fault-line when it came to the acceptance or rejection of Hadith in early Islam.

For the full paper from where this is taken: shiiticstudies.com/2024/11/05/pro…

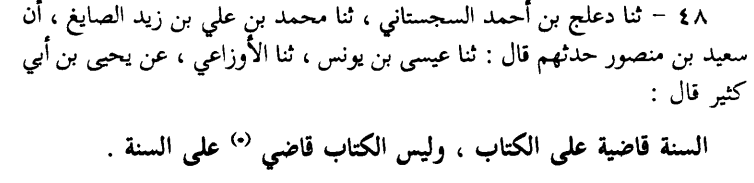

References: Al-Umm (ed. Rifʿat Fawzī ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib), v. 8, pp. 35-36, nn. 2998-2999; Ibn Shāhīn’s (d. 385) Sharḥ Madhāhib Ahl al-Sunna (ed. Muʾassasat Qurṭuba), p. 46, n. 48;

Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr’s (d. 463) Jāmiʿ Bayān al-ʿIlm wa Faḍluh (ed. Dār Ibn al-Jawzī), v. 2, p. 1191, n. 2347; Al-Radd ʿalā Siyar al-Awzāʿī (ed. Abū al-Wafāʾ al-Afghānī), pp. 24-25; Al-Risāla (ed. Aḥmad Muḥammad Shākir), pp. 224-225, nn. 617-618;

Tahdhīb al-Kamāl (ed. Bashshār ʿAwwād Maʿrūf), v. 8, pp. 156-157, n. 1647; Al-Kāfī (ed. Dār al-Ḥadīth), v. 1, pp. 173-174, n. 207.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh