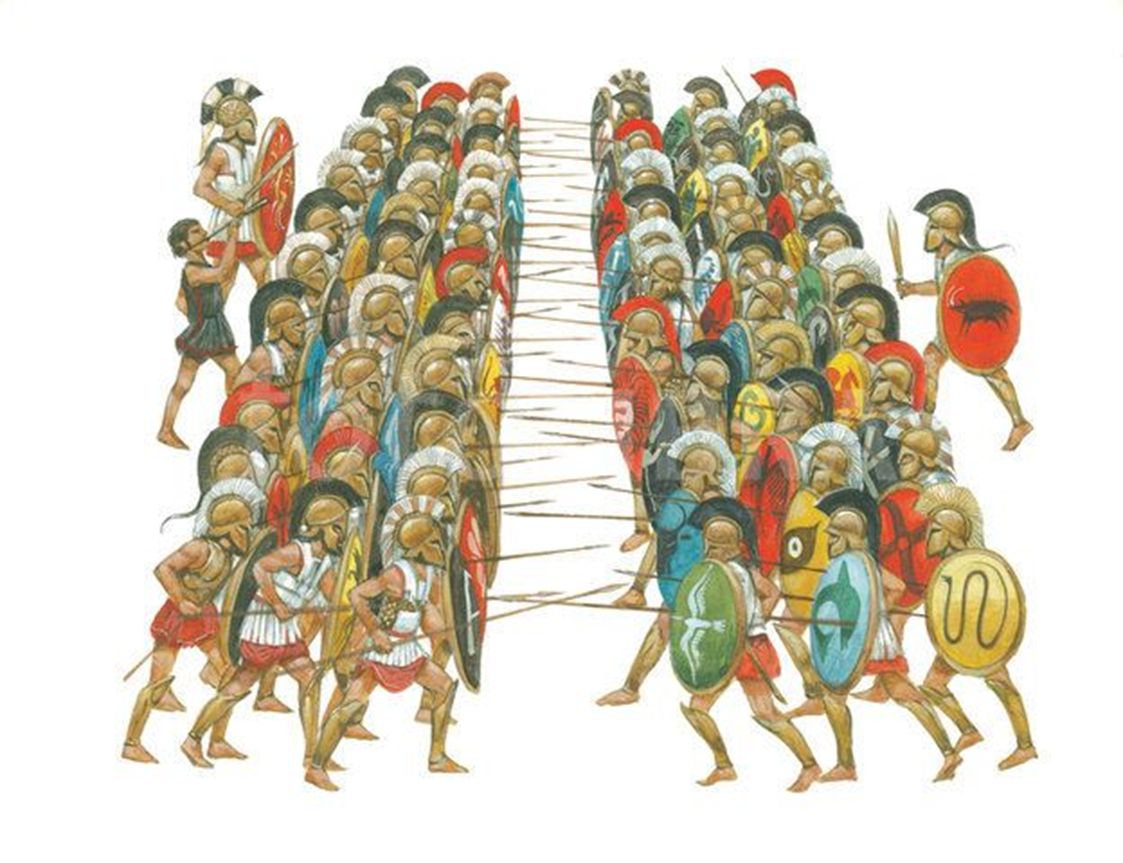

How in the world do you beat this formation?

Well, it was virtually unstoppable when it was first used in battle—it toppled an empire and became the default fighting formation of the ancient Greek world.

An introduction to the Macedonian phalanx…🧵

Well, it was virtually unstoppable when it was first used in battle—it toppled an empire and became the default fighting formation of the ancient Greek world.

An introduction to the Macedonian phalanx…🧵

You’ve probably heard about Alexander the Great’s conquest of the ancient world—what’s lesser known is that much of his success was due to his father Philip II.

Specifically, it was Philip who created a game-changing new infantry formation called the Macedonian phalanx.

Specifically, it was Philip who created a game-changing new infantry formation called the Macedonian phalanx.

Phillip, a former hostage of Thebes for much of his youth, witnessed the innovative combat tactics of the great general Epaminondas, who had led Thebes out of Spartan subjugation.

Perhaps Philip was inspired by Epaminondas to introduce his own innovation his army...

Perhaps Philip was inspired by Epaminondas to introduce his own innovation his army...

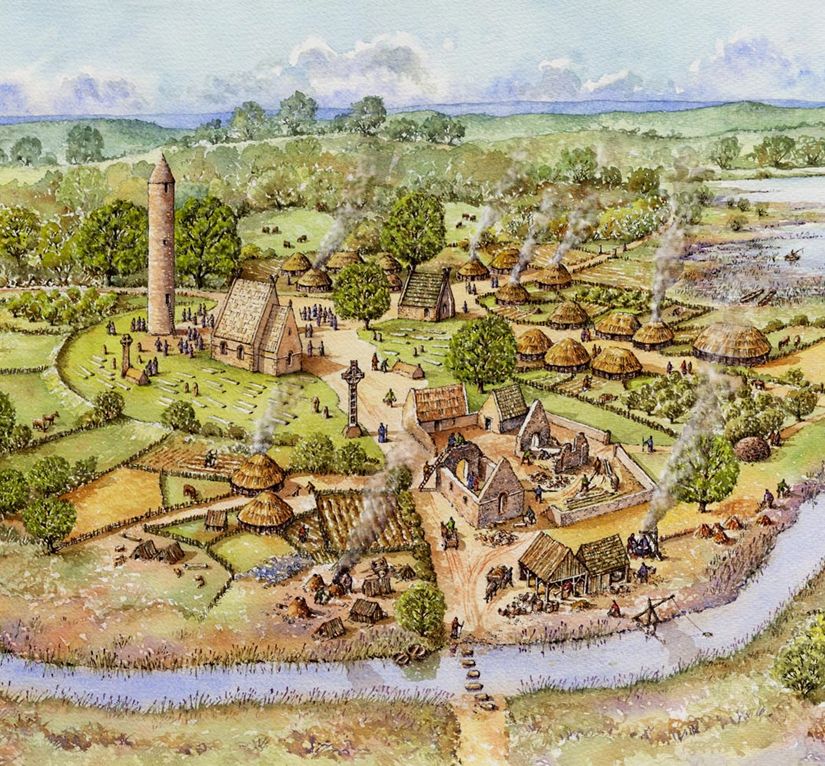

Phalanxes had been used long before Philip’s time. There’s a depiction of Sumerian’s using a phalanx on a monument called the Stele of the Vultures which dates to 2400 BC.

And the traditional Greek hoplite phalanx emerged around the 7th-8th centuries BC.

And the traditional Greek hoplite phalanx emerged around the 7th-8th centuries BC.

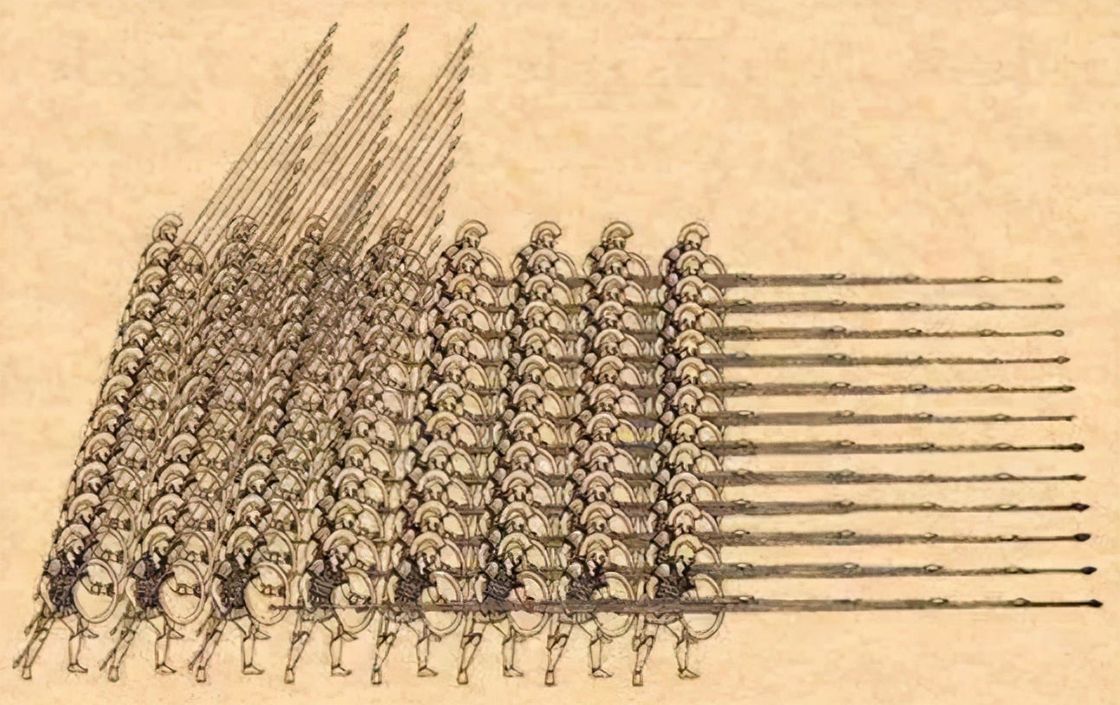

The term “phalanx” simply refers to a rectangular military formation composed of tightly packed infantry armed with spears.

It was the most widely used formation in the Greek world, but Philip made a slight adjustment that changed everything…

It was the most widely used formation in the Greek world, but Philip made a slight adjustment that changed everything…

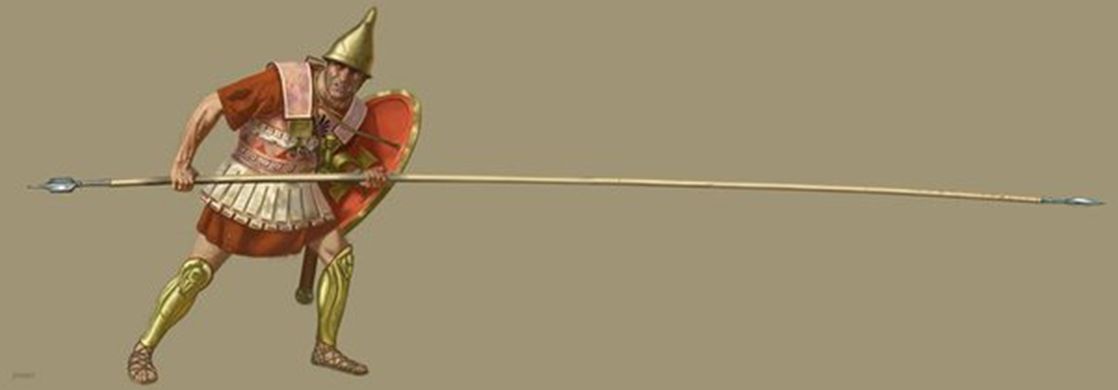

Typically, a Greek hoplite carried an 8-foot spear called a dory. This was used all around the ancient world. It was great for piercing the gaps of an enemy’s bronze armor and for use in tight formation where it could be overlapped with allies’ spears.

Instead of the dory, Phillip equipped his army with a much longer spear called a sarissa. These were roughly ~16-23 feet long which allowed them to outreach the dory.

When they were overlapped by multiple rows of fighters, a spear wall 5 layers thick would confront the enemy.

When they were overlapped by multiple rows of fighters, a spear wall 5 layers thick would confront the enemy.

When the phalanx was used with the sarissa, enemies had a difficult time even reaching the Macedonians to engage them in combat—it was basically impossible to penetrate the spear wall.

In addition to the inclusion of the sarissa, Philip ensured a highly disciplined force and standardized the phalanx formation.

The 16-man-wide by 16-man-deep block of warriors became a fighting machine under Philip.

The 16-man-wide by 16-man-deep block of warriors became a fighting machine under Philip.

Little changed for the Macedonian phalanx when Alexander took the reins of power, but he introduced it to the world in legendary fashion with his conquest of the East.

The world would never be the same once Alexander let it loose.

The world would never be the same once Alexander let it loose.

In Alexander’s formation, the phalanx formed the bulk of his army and was used to hold the enemy in place while his heavy cavalry, arranged in a “wedge” formation, broke through their ranks.

Often the fighting was forced to his right flank where the cavalry were concentrated.

Often the fighting was forced to his right flank where the cavalry were concentrated.

The first five rows would point their spears forward creating an impenetrable spearwall, while back rows would angle their spears upward, waiting to take the place of a fallen comrade. These back rows also provided raw mass to maintain the integrity of the unit.

Each soldier, or phalangite, in the Macedonian phalanx had several pieces of equipment besides the sarissa.

Since the long sarissa was ineffective close up, phalangites carried a shortsword called a xiphos which could be deployed in case enemies broke through the spear wall.

Since the long sarissa was ineffective close up, phalangites carried a shortsword called a xiphos which could be deployed in case enemies broke through the spear wall.

Phalangites also carried a shield, called a telamon, which was essential to the phalanx because each man protected the soldier next to him with it.

Since every man depended on his fellow warrior, you can imagine the strong bond that was formed between the troops!

Since every man depended on his fellow warrior, you can imagine the strong bond that was formed between the troops!

After Alexander proved the effectiveness of the Macedonian phalanx, it spread throughout the Hellenic world and became a very popular military formation for the Greeks.

It only had one weakness…

It only had one weakness…

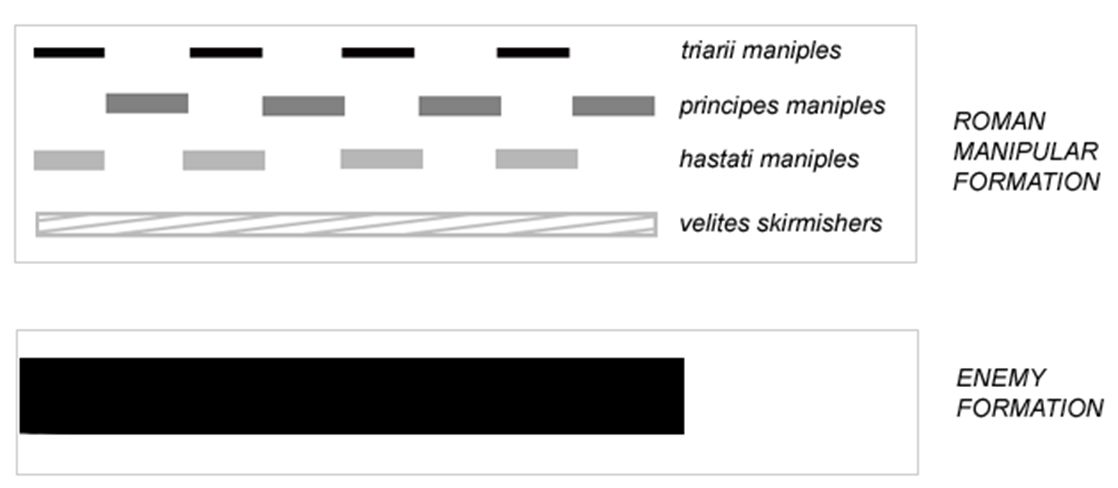

During Rome's conquest of Greece in the late 3rd/early 2nd century BC, they exploited the Macedonian army’s inability to maneuver while in formation and devastated their flanks and rear.

Rome’s legions — made up of highly maneuverable arrayed units — prevailed.

Rome’s legions — made up of highly maneuverable arrayed units — prevailed.

The Macedonian phalanx essentially spread Greek culture to the ends of the known world.

Without Phillip’s innovation, history may have turned out much differently, and Alexander may have never become “the Great” we know him as today.

Without Phillip’s innovation, history may have turned out much differently, and Alexander may have never become “the Great” we know him as today.

If you enjoy this type of content here, you might like our YouTube channel. We discuss similar topics over there and would appreciate the follow!

youtube.com/@thinkingwest?…

youtube.com/@thinkingwest?…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh