Why is Tokyo so fashionable? Some theories. 🧵

https://twitter.com/esaagar/status/1861555703497822477

Any time someone discusses social outcomes, the easy answer is "culture." That's because anything can be explained away by culture (e.g., "oh that's just the way those people are; it's their culture"). When discussing Asia, sometimes this can get into weird orientalism.

When I was on a menswear forum, I remember discussing the question of why there are so many bespoke shoemakers in Tokyo. Some said "it's because the Japanese value craftsmanship. They are noble, not like wasteful Westerners." This sort of handwaving feels unsatisfying to me.

In this thread, I will explore some ideas on why Tokyo is so fashionable. Some of it does have to do with culture, but as you'll see in the thread, culture is also shaped by political, economic, and institutional forces. IMO, one should look for structural reasons for outcomes.

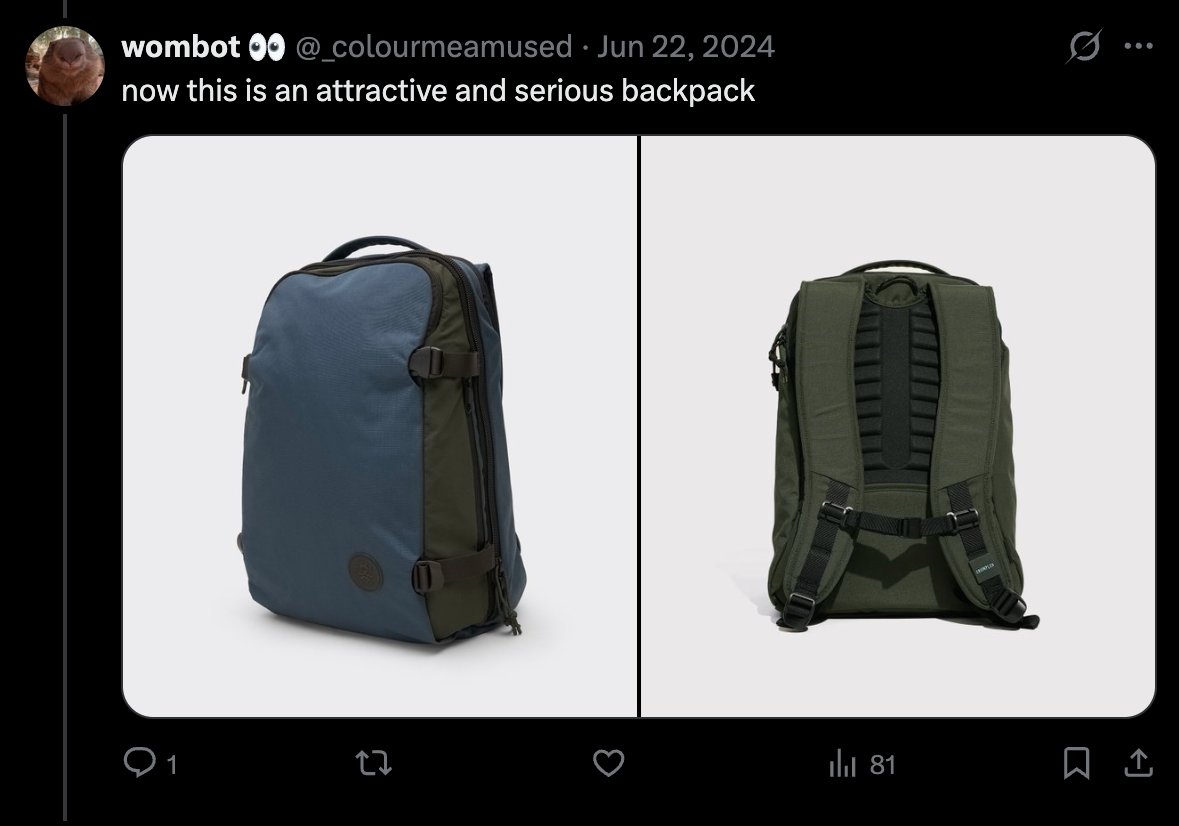

A big reason why Tokyo is more fashionable has to do with the media environment. There are thousands of hobbyist magazines covering topics ranging from woodworking to whisky. In menswear, they can get very specific in terms of aesthetic: outdoorsy style, classic, workwear, etc.

It's interesting to me to see the difference between US and Japanese fashion media. Whereas US media tends to focus on celebs and ideas on how to break the rules (or the idea that there are no rules and you can do anything you want), Japanese media explores rules and details

Here are some scans from Men's Ex on how to shine shoes. The last scan (I think from Free & Easy) explores the teeny, tiny differences between nine pair of full-cut chinos. The Japanese word otaku refers to nerds who are obsessed with these niche hobbyist details.

In addition to magazines, there are also one-off hobbyist publications, clearly made as a labor of love. Here's one on shoes. Inside, it explores iconic styles, construction techniques, and even different ways to tie your shoes (trust me, menswear nerds have rules for this).

"Oh, but this just shows the nerdy, detail-obsessed nature of Japanese people," you say. Perhaps. But these publications can't exist without a distribution system (newsstands), and those newsstands can't exist without dense *walkable neighborhoods.*

Along with having better fashion media, Tokyo has better shopping opportunities than most US cities. There are stores with racks of just vintage Aldens (and magazines that can help you date them by their labels). Also more bespoke tailors and shoemakers than all of the US

Are you into sleazy, glamorous, 1970s styled eyewear? There's a whole store dedicated to that (Solakzade), as well as nearby shops selling the rayon shirts, bootcut pants, side zip boots and jewelry you'll want to wear with your new eyewear purchase.

Are you into denim, Americana, and mid-century workwear? There are stores that sell brands recreating the exact materials and Talon zippers once used on military clothing (bought buy guys who are obsessed with these details bc they read about it in a magazine).

YT ChiemyChanga

YT ChiemyChanga

My friend Seiji is a bespoke shoemaker. He was born in the US but moved to Tokyo some years ago to train under a master bespoke shoemaker. Now he runs his own independent shop. I call his style "elevated Alden" bc the shapes are so American (I love them).

IG seijimccarthy

IG seijimccarthy

He tells me he can pursue his dream of working as a bespoke shoemaker because the cost of living is low (specifically, rent). You can rent a tiny space in Tokyo for very little money, whereas commercial space in the US tends to be both big and expensive

When a commercial space is both big and expensive, the tenants tend to be deep-pocketed corporations. So instead of an independent perfumer, you get Sephora. Instead of an brand selling niche workwear, you get J. Crew. This leads to homogenization in fashion (and culture).

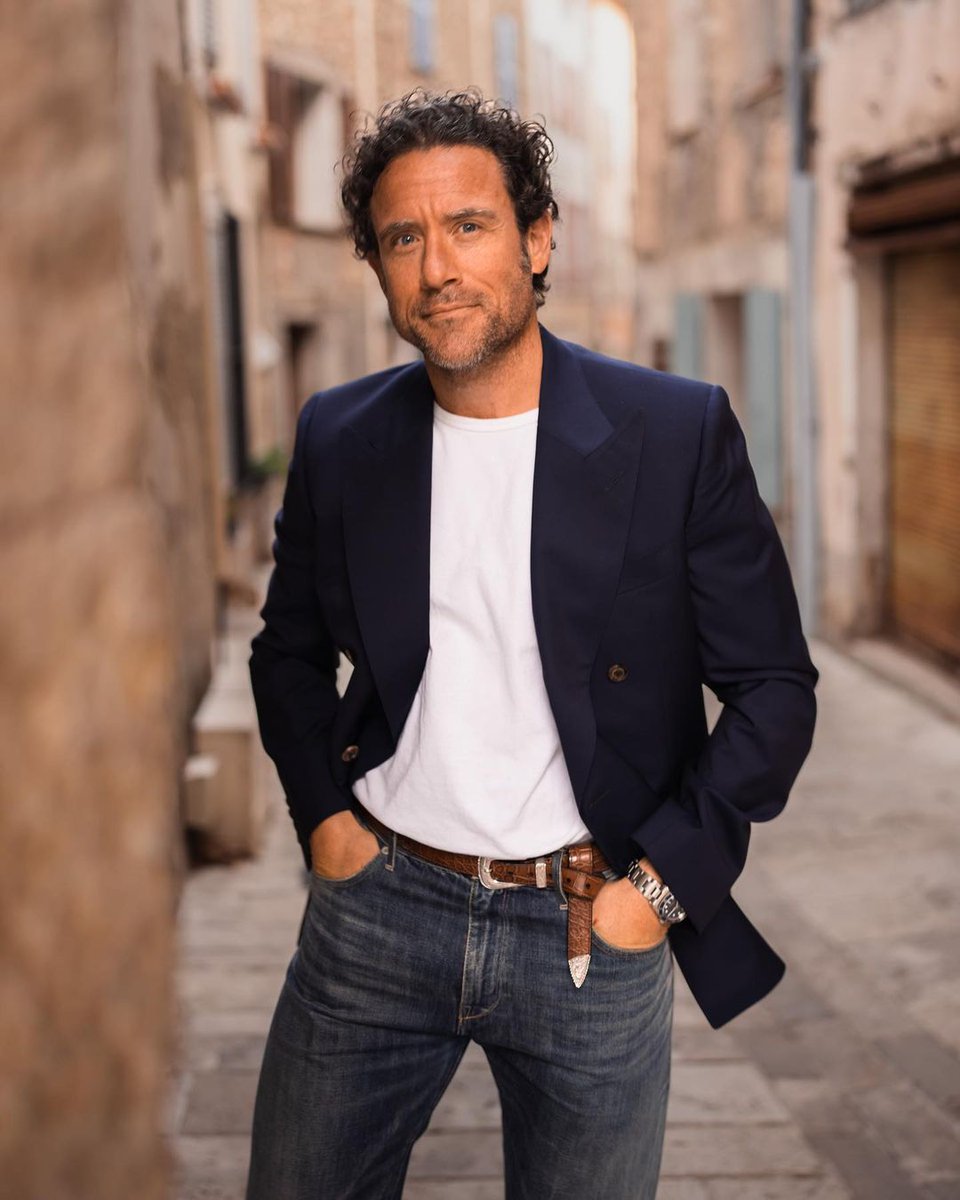

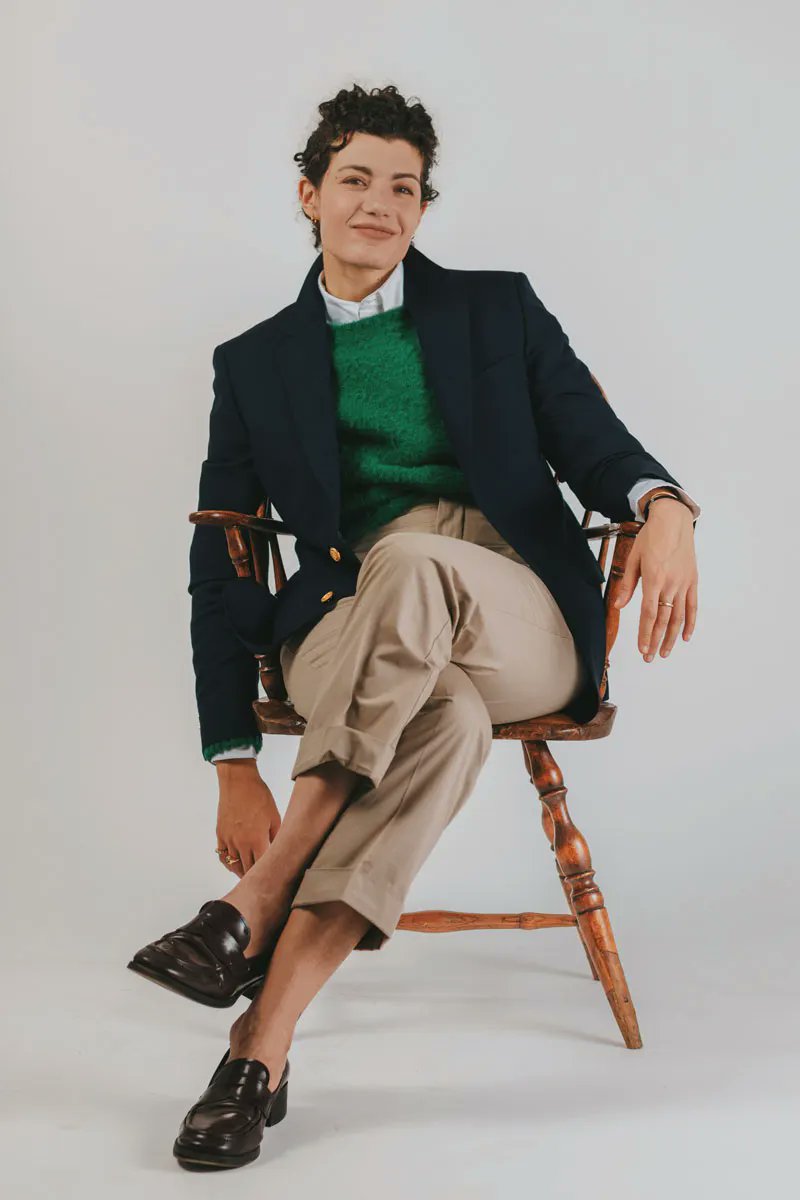

Compare that to Tailor CAID, a bespoke tailoring boutique that specializes in mid-century American style tailoring. That means three-roll-two jackets, two-button cuffs, machine-finished lapels, dartless front, hook vent, and natural shoulder tailoring.

The proprietor, Yuhei Yamamoto, makes clothes for guys who are *passionate* about classic American style. In these circles, social cache is not gained through innovation but by demonstrating that you can correctly execute the look. That means digging deep into details.

Some of this is covered through @wdavidmarx's book Ametora, which explores how Japan saved American style after we abandoned it. There are specific people who shaped this fashion culture in Japan (and wonderful stories about how things such as vintage style became cool)

Tokyo is not just about vintage style. In Harajuku, lots of young people are wearing cosplay, goth/ punk, avant-garde, and other types of fashions. The styles here may seem innovative, but they are also very much about a subculture's "rules." It's not totally random.

Culture tends to build on itself. In Kojima, Momotaro is making handcrafted, artisanal jeans that can sell upwards of $2,000. The price is not about some celeb who wore it, but rather how much time and skill goes into making the garment.

YouTube BusinessInsider

YouTube BusinessInsider

The amazing denim industry in Japan means that Kapital, a store in Tokyo, can sell specialized, innovative jeans based on deep research and craft skills. And there are customers who know what they're buying.

YouTube iwantvag69

YouTube iwantvag69

IMO, when asking why something is the way it is, we shouldn't just fall back on easy answers like "culture" or the "character of the people." Such answers are often just the first go-to when someone doesn't know very much about a subject.

Instead, we should look to history, path dependency, institutional structures, politics, and economics. For Tokyo, I think urban planning—walkability, mixed use neighborhoods, affordable real estate—all contribute to the richer media and commercial systems that feed into culture.

The book Emergent Tokyo isn't necessarily about fashion but it touches on some of these urban planning issues.

IMO, looking at historical and institutional structures like this helps us explain why culture is the way it is, and gives us more traction on how to change ours.

IMO, looking at historical and institutional structures like this helps us explain why culture is the way it is, and gives us more traction on how to change ours.

If we want better fashion culture in the US, we have to lower the cost of housing and commercial real estate, support independent craftspeople, build denser neighborhoods, improve walkability, and get rid of overly restrictive zoning laws. Let kook culture thrive.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh