I'll explain what these are and why they're great. 🧵

https://twitter.com/SarahMya2000/status/1862580245011878358

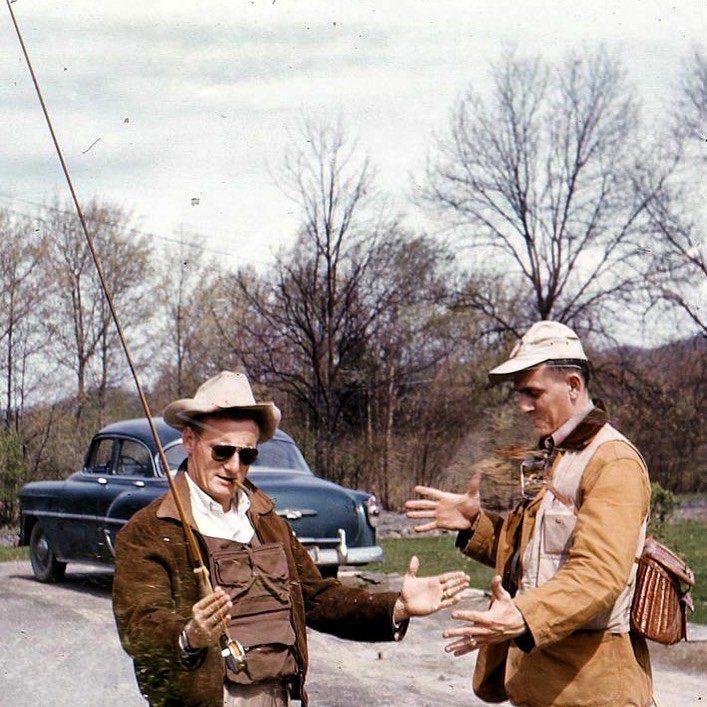

Sometime during the early 20th century, American outdoorsman Leon Leonwood Bean faced a problem: how do you keep your feet dry while hunting in wilderness of western Maine? Waders are fine in the water but you don't always want to be wearing those on dry land.

So he came up with a hybrid: a hunting boot that had the flexibility of a traditional leather upper but with the water-resistance of rubber footwear. First made in his basement, the two parts were combined with triple-line stitching to ensure they'd never separate.

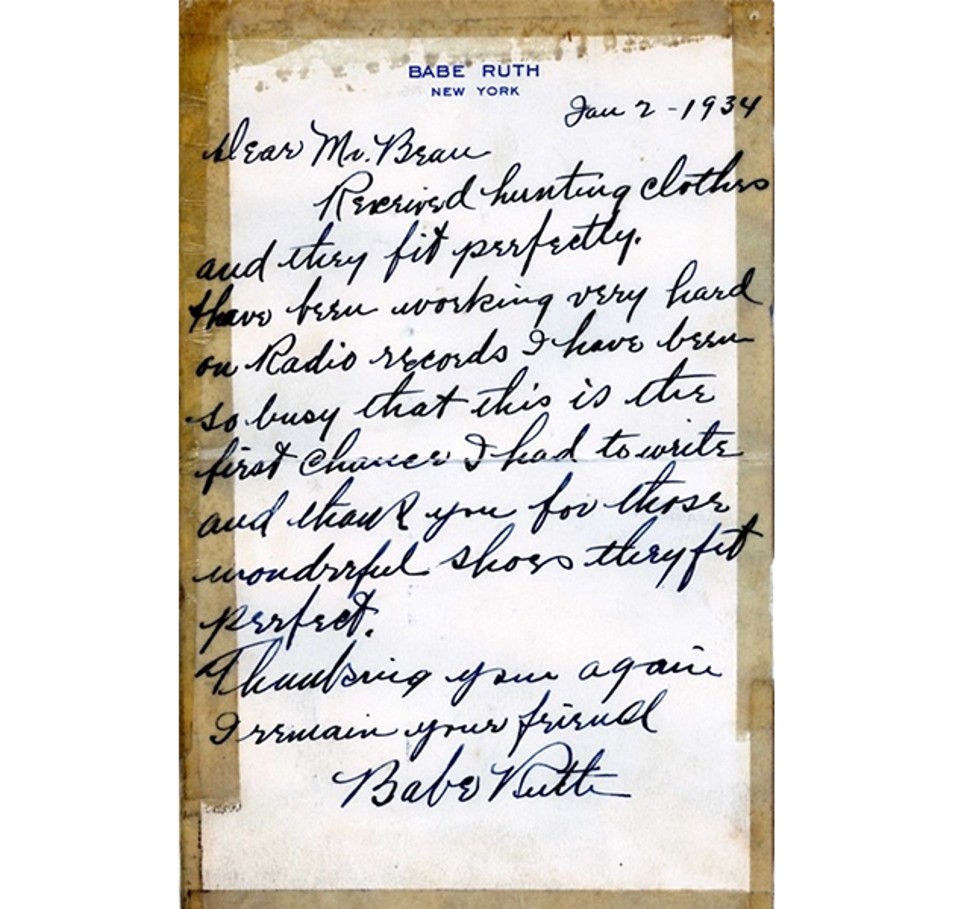

Leon Leonwood Bean debuted his Maine Hunting Shoe through his company LL Bean in 1912. They were a hit with sportsmen; even Babe Ruth was a fan. "Thank you for those wonderful shoes, they fit perfect," Ruth wrote Bean in a letter. "I remain your friend."

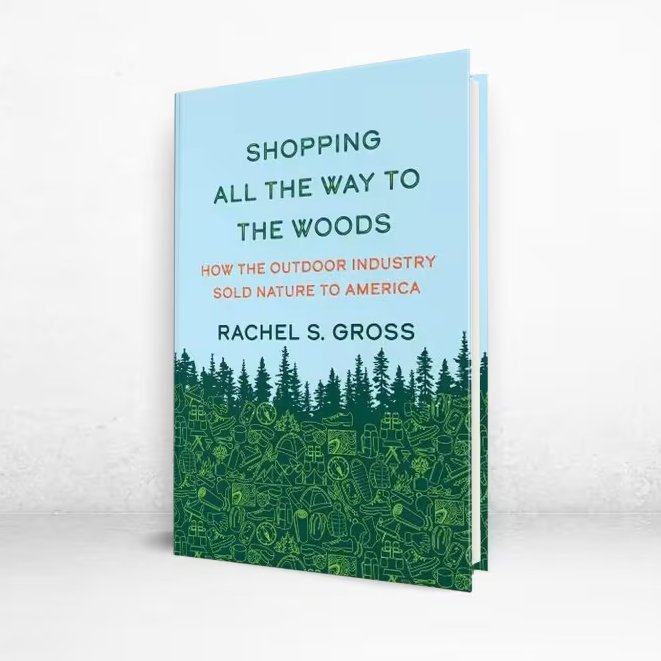

Over the next 50 years or so, LL Bean—much like other outdoor clothing brands—expanded and became more of a lifestyle company, a dynamic that environmental and cultural historian Rachel Gross brilliantly explores in her book Shopping All The Way to the Woods.

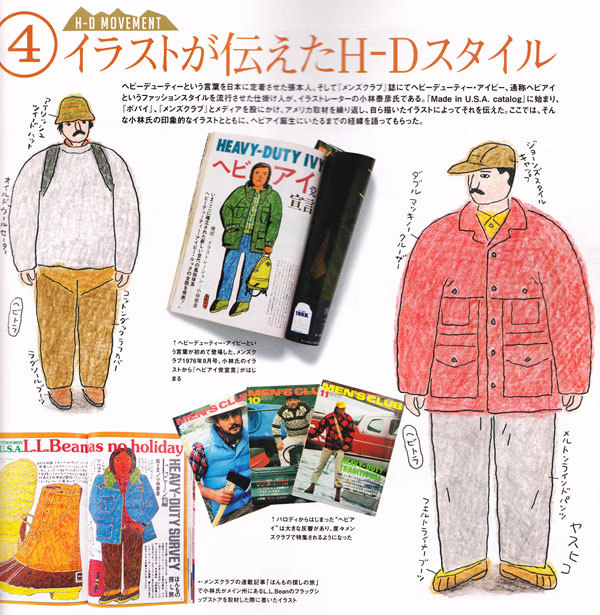

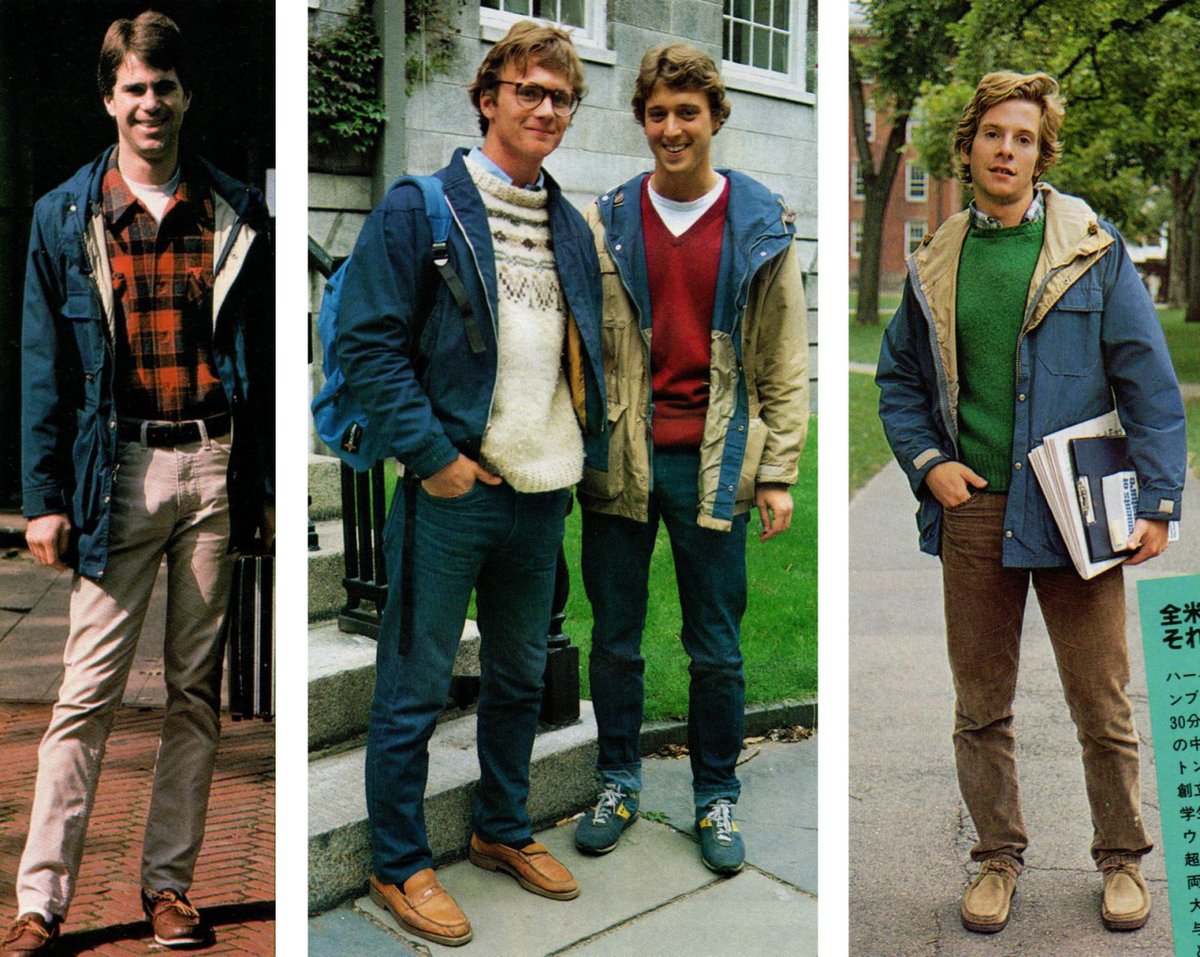

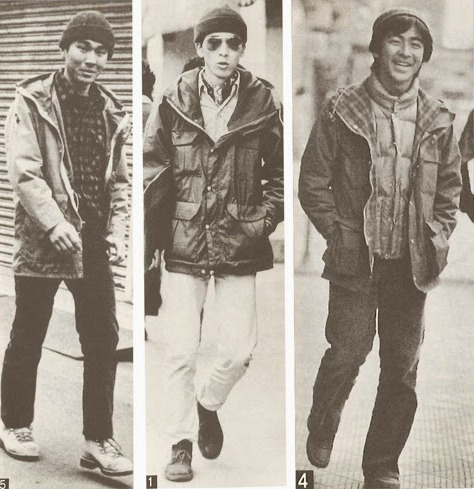

That means the boots were no longer just part of the standard kit for Maine hunters, but rather preppy students across the Midwest and Northeast. In his book Ametora, David Marx calls this style Rugged Ivy, as it was the outdoorsy counterpart to academic tweeds and blazers.

Yes, much of this look was based on outdoorsy apparel built for function, but the styles were now about semiotics. They were worn for cultural identity, often signaling that the person aspired to have a connection with the outdoors. LL Bean boots were part of this look.

After about the 1980s, a lot of classic American style died in the US. I'm talking about classic tailoring, workwear, 1970s outdoor style, Rugged Ivy, and the like. Americans moved on to other trends. But the style lived on in Japan, where it became part of menswear culture.

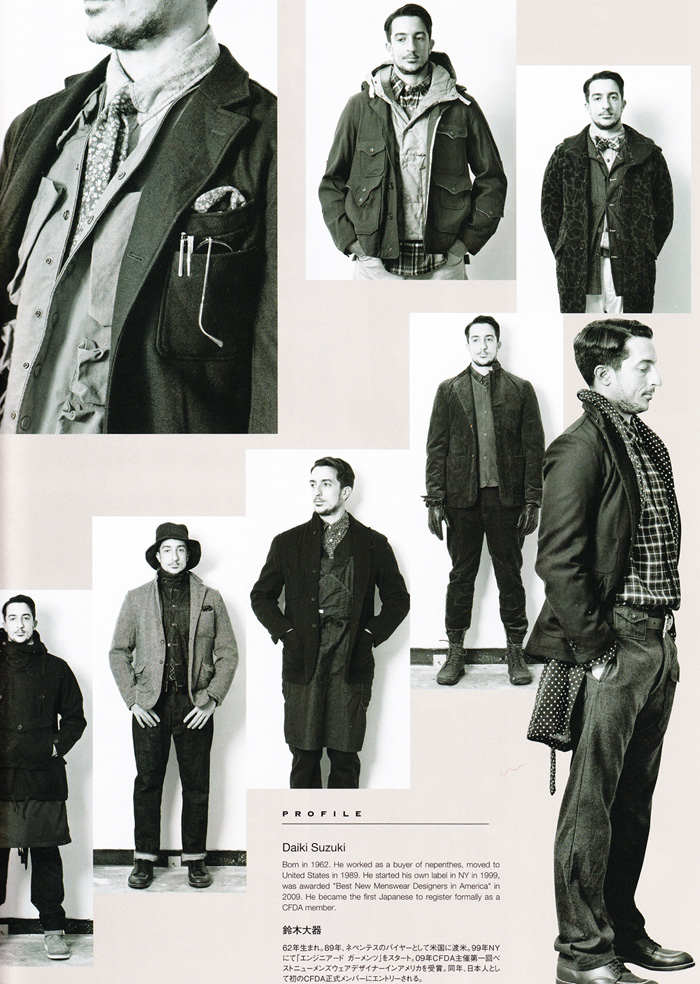

So it's no surprise that the best Americana brands nowadays are not based in the US, but rather Japan. That's where you find both a true commitment to the original spirit of that mid-century look, as well as innovation. See how Engineered Garments riffs off American workwear.

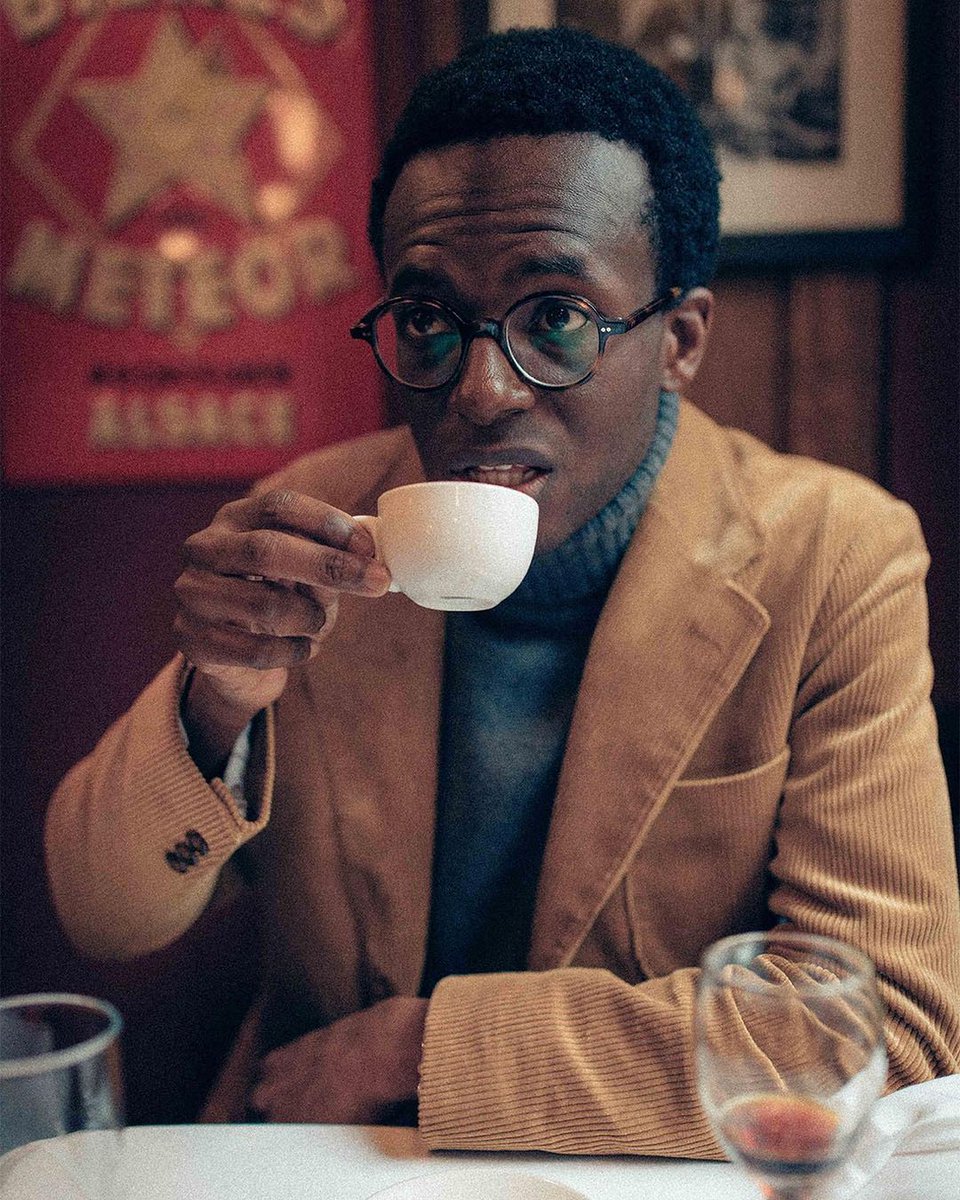

Visvim, the company that made the boot in the original tweet, is one of the many Japanese brands focused on heritage American styles. To be honest, sometimes I think the brand runs a little on how cool the founder, Hiroki Nakamura, looks. Everyone wants to look like him.

Visvim's prices are a running joke in menswear circles because prices seem to go up every year. They are stratospherically high and seem to only be getting more out of reach. But I will say: when you actually get to handle the items, there's a lot of impressive detailing.

Some fabrics are handwoven, hand-dyed, and hand screen printed. One can squabble about the value of these methods. I've argued on forums that their "handmade Goodyear welt" doesn't add much bc it still has gemming. But there's still a craft element in their collections.

So yes, these shoes are "ugly." They look alien, bulbous, and bulky. But they're an offbeat Japanese version of a classic American hunting shoe. To me, they tell a story about how classic American style has been preserved by enthusiasts in Japan who love the look more than us.

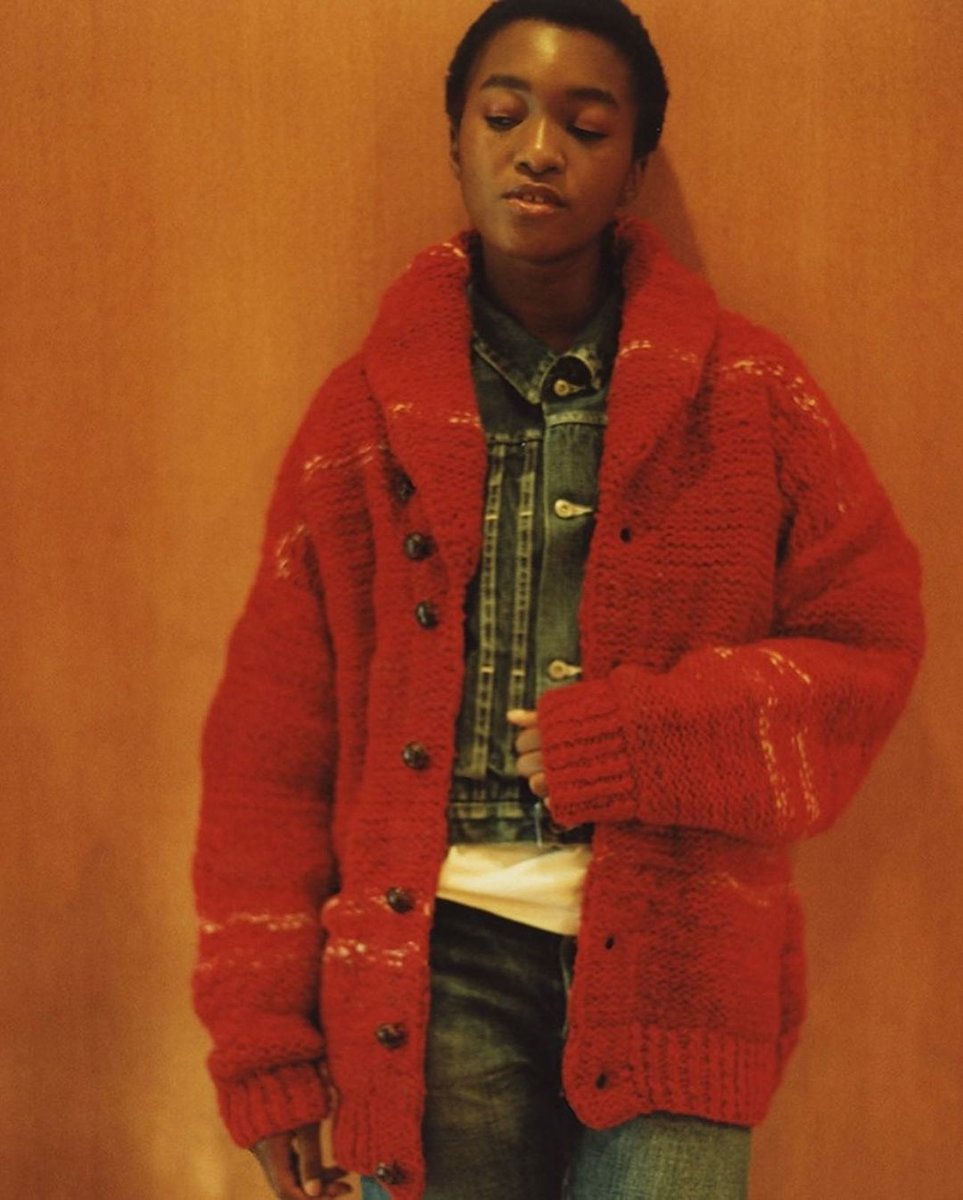

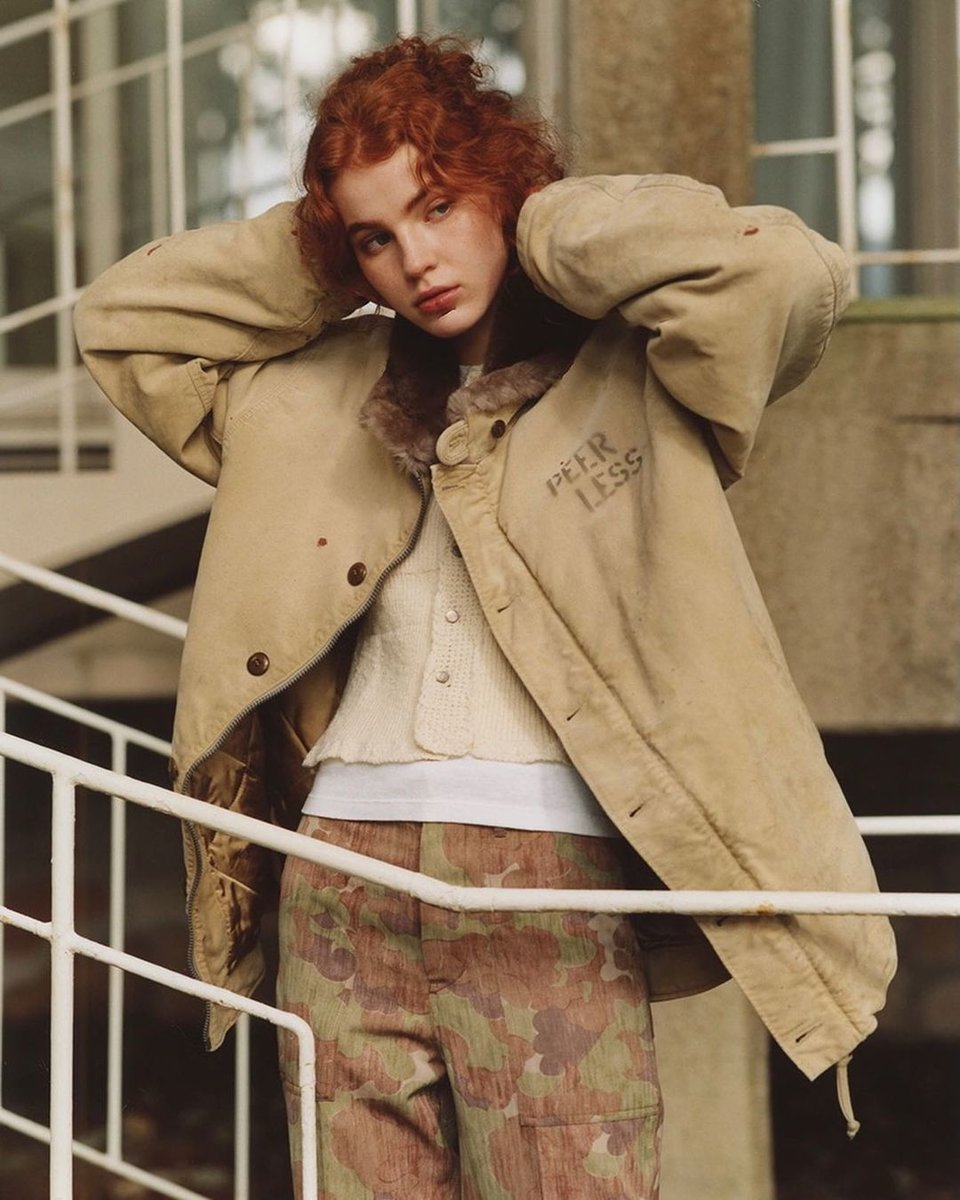

I also think they can look great in the right outfits: chore coats, deck jackets, fatigues, wide legged jeans, duffle coats, and Cowichan knits. The chunkier proportions play better if all the other things in your outfit are similarly riffs on classic Americana.

For guys who love that style but don't want to look preppy, Visvim's decoy duck boot can be a fun alternative to the original (pic 1). Their have more of a streetwear/ workwear/ fashiony feel. They also do a version with a thicker sole, although that's more directional (pic 2)

someone trying to be friendly at a party: "what are thooossee?"

me: "i'll tell you what are these. 🧵"

me: "i'll tell you what are these. 🧵"

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh