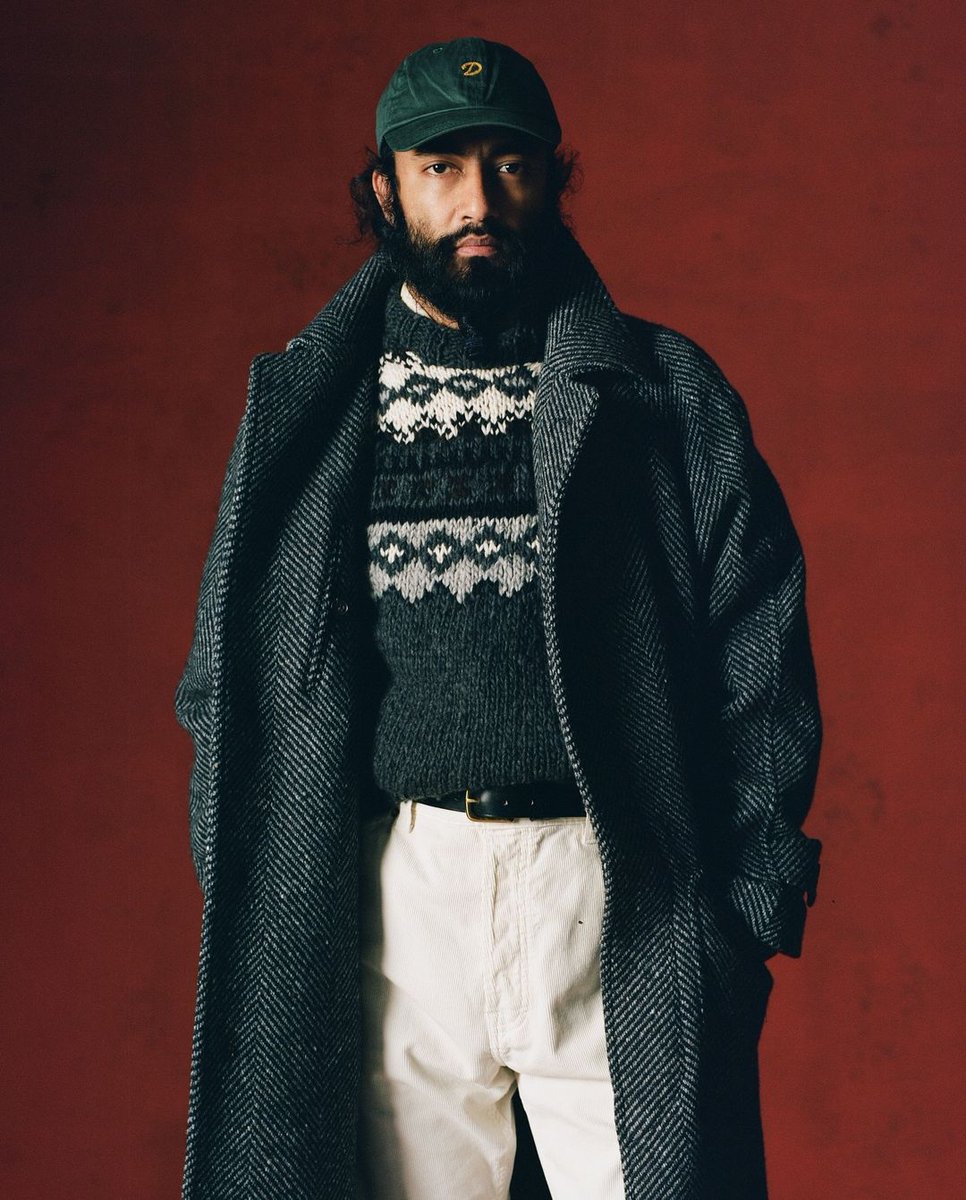

I'm happy to explain why that sweater is $500. 🧵

https://twitter.com/AmrananmAnRa/status/1862651203353526642

I should note that I know not everyone can afford a $500 sweater. That's why my Black Friday post includes things such as this $80 J. Crew sweater. In the past, I've also written guides on how to to get top-of-the-line vintage Scottish cashmere knits on eBay for ~$50.

But since I appreciate craft and wish to see craftspeople be able to earn a living, I'm also happy to promote things that I think help keep these traditions alive.

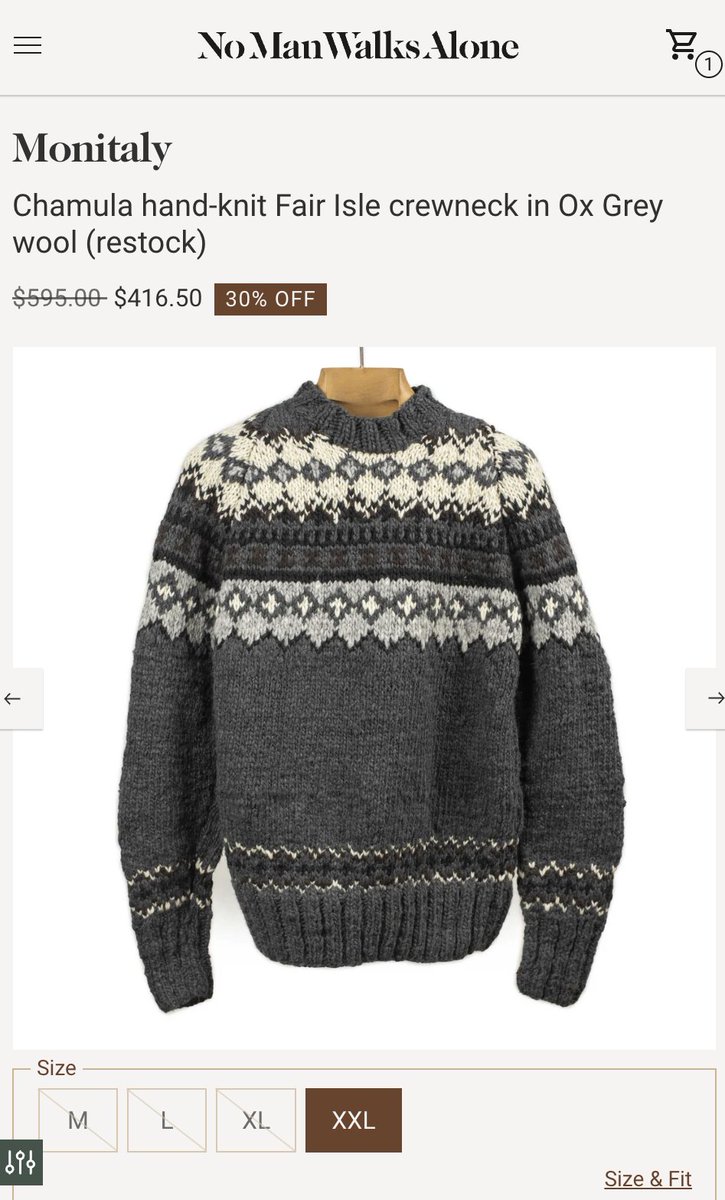

So, why is this Chamula sweater $500? It's because of how it was made.

So, why is this Chamula sweater $500? It's because of how it was made.

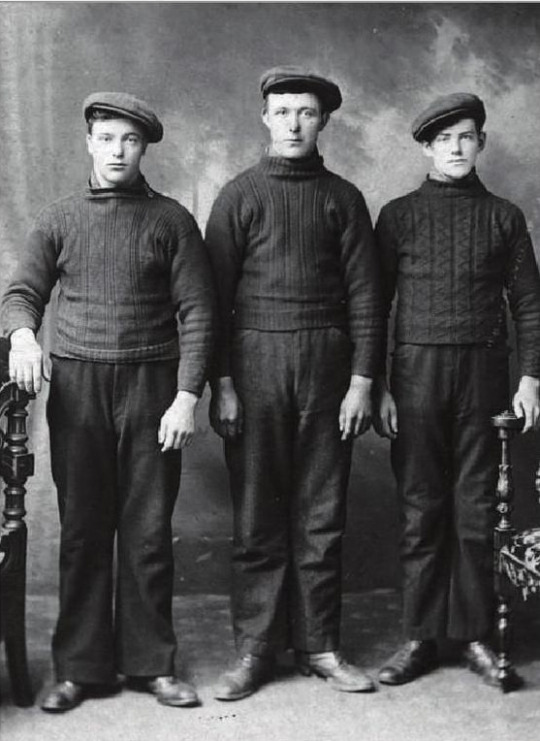

Most sweaters are made on flat bed or circular knitting machines. If the manufacturer is good, they'll hand-link the panels together so the finished product doesn't have a bumpy seam. When shopping, look for something called a "fully fashioned" sweater. It's a sign of quality.

The amount of industrial technology in this process allows you to buy a pretty good sweater for $200 or less. But there are also companies that produce sweaters the old fashioned way: by hand.

Chamula is one of those companies. Here is the brand's founder, Yuki Matsuda

Chamula is one of those companies. Here is the brand's founder, Yuki Matsuda

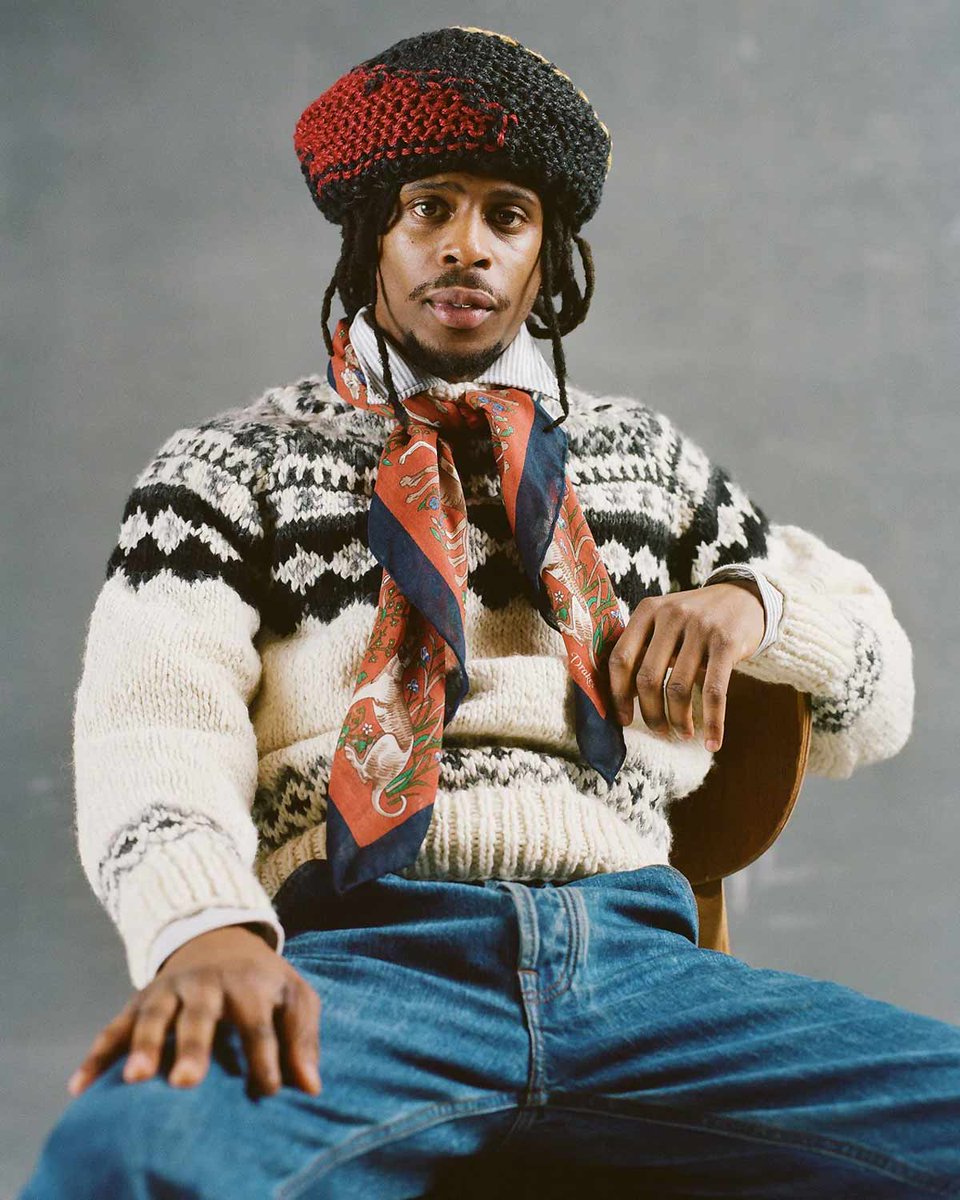

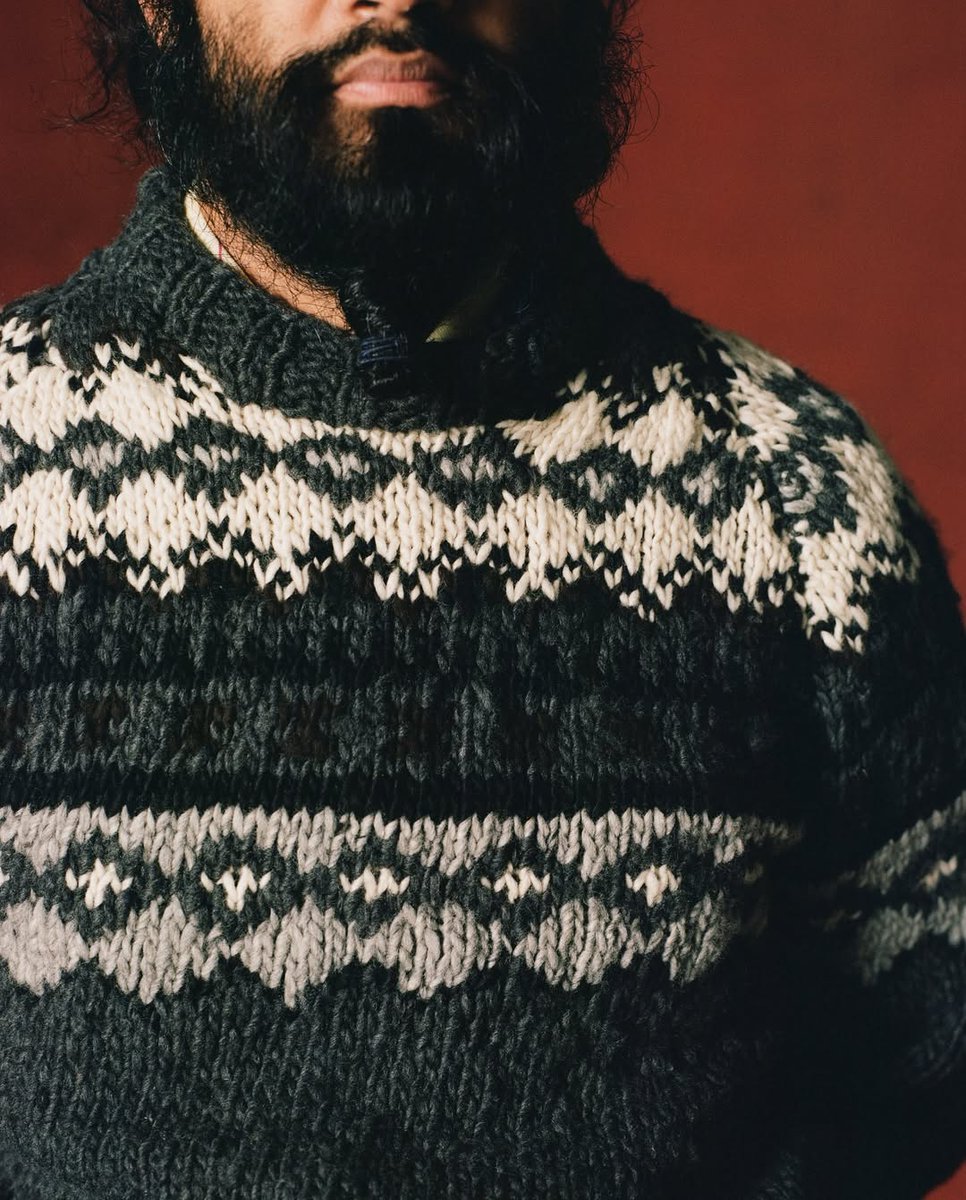

Chamula uses Merino yarns sourced from pure bred sheep grazing on mountains in Mexico. These fibers are then hand-spun on spinning wheels and then hand-dyed into rich colors. The resulting yarns are given to indigenous Mexican knitters who hand-knit them into sweaters.

Does the amount of handwork make for a better sweater? Well, it depends on what you mean by "better."

Depending on the design, hand-knitting a sweater can sometimes produce intricate stitches not possible on a machine. Depending on the process, you can also get customization.

Depending on the design, hand-knitting a sweater can sometimes produce intricate stitches not possible on a machine. Depending on the process, you can also get customization.

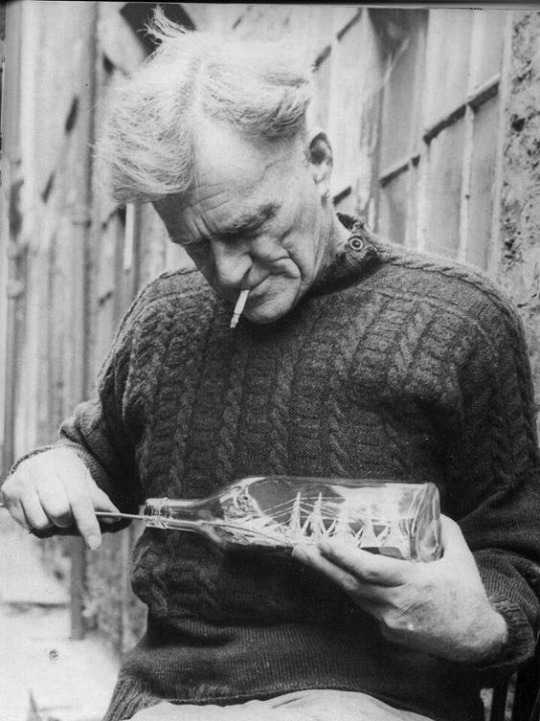

Flamborough Marine is one of my favorite producers for handknit sweaters. They make in a fisherman style known as the guernsey (sometimes spelled gansey), which has identical panels from front-to-back and features a high neck collar and dropped shoulder seams.

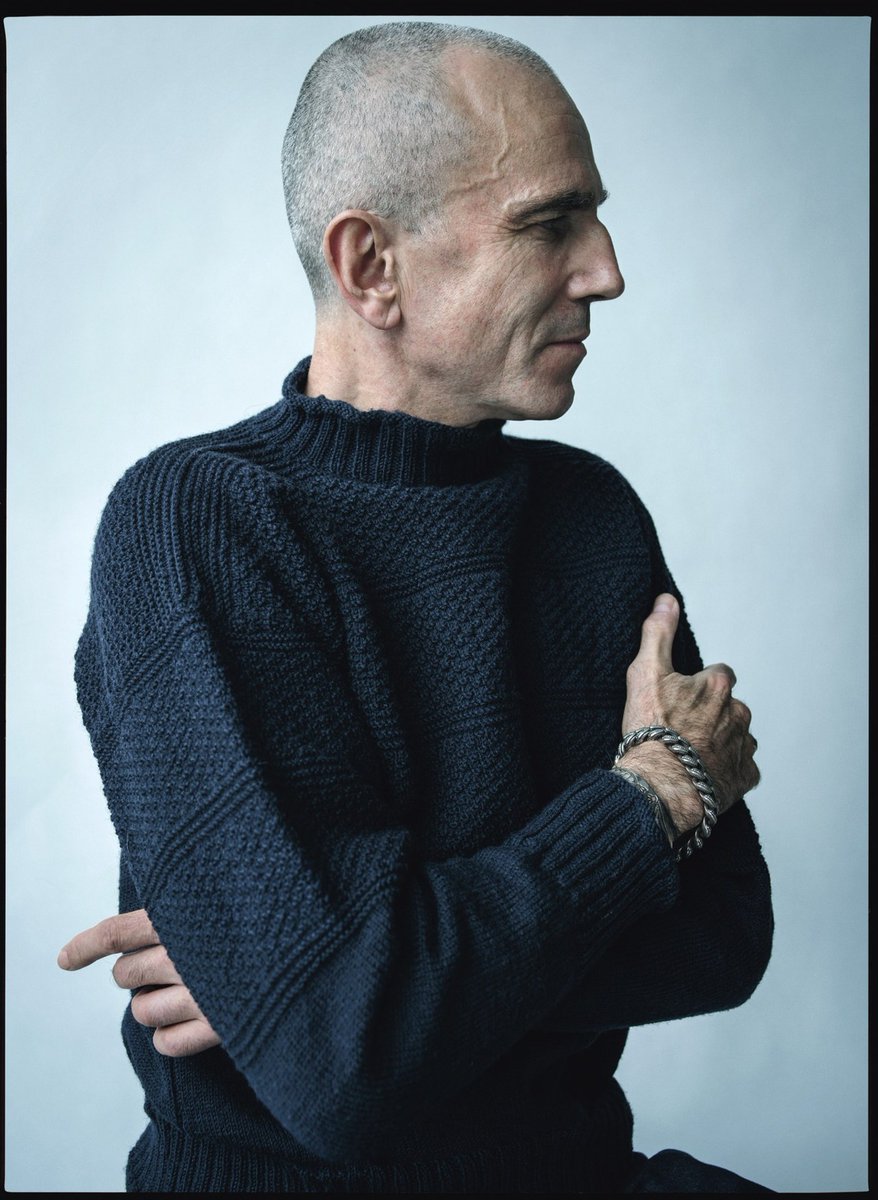

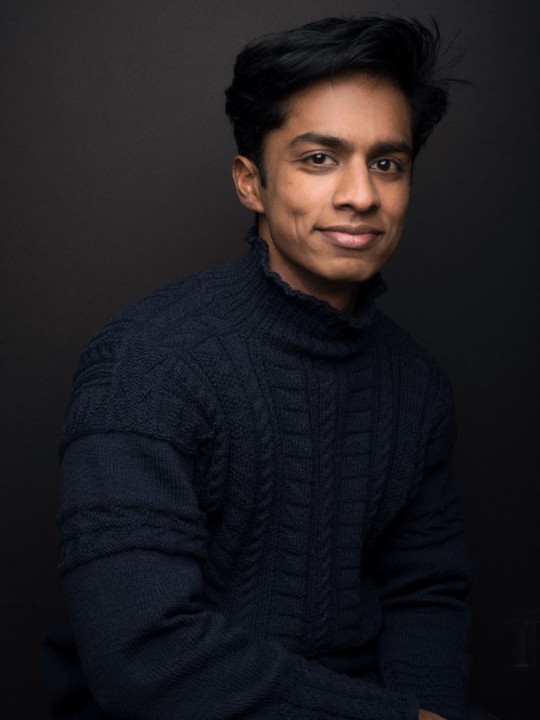

Daniel Day-Lewis once had a sweater made here. He said it was inspired by a fisherman knit once owned by his late father, Cecil Day-Lewis, and had a similar design made through Flamborough Marine. Rajiv Surendra also owns a sweater from the company.

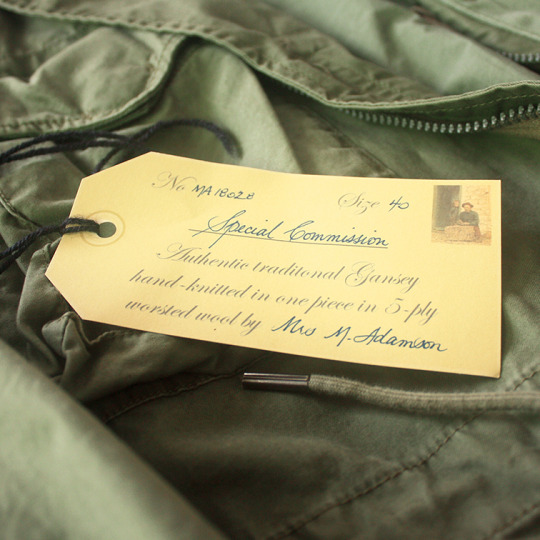

These knits are itchy, dense, and wonderful. They function like windproof outerwear. Since each sweater is fully handmade and knitted upon order, you can ask for anything you want. When delivered, the sweater comes with a little card signed by your knitter.

Cost? About $625.

Cost? About $625.

Chamula's sweaters are ready-made, not custom, and they're not as dense or windproof as Flamborough Marine's guernseys. Instead, the yarns are extremely plush and spongey; the low gauge means you get a slightly looser, more open knit.

I treat mine a little more delicately than I would, say, a standard machine-knit Shetland. But I love the unique texture they bring to an outfit. I also love that these were made by hand from start to finish by indigenous Mexican knitters carrying a craft tradition forward.

The $500 price reflects the time and skill that goes into these garments. Is hand-knitting better? Not necessarily, but if you fall in love with the process, perhaps you'll love and treat the knit with more care. And be more likely to repair and wear the sweater for a long time.

That said, I think you can appreciate something without wanting to own or purchase it. The price alone should not be reason for ridicule. Workers deserve fair pay, and even if you can't afford to buy something, you can appreciate that someone is laboring to keep a craft alive.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh