On the morning of November 28, China's newest nuclear power plant, a Hualong One reactor at Zhangzhou in Fujian, connected to the grid just just 61 months after construction.

How does China build these so fast? Let's review the timeline. 🧵

How does China build these so fast? Let's review the timeline. 🧵

The first thing to know about Zhangzhou NPP is it's NOT a new reactor. Actually this thing has been planned for AGES.

The first mention I can find of it goes back to 2007, when Guodian (one of the plant owners) set up a Project Office in Zhangzhou.

We learn from this very early notice that the site plans to use AP1000 reactors imported from Westinghouse. Keep in mind, the Westinghouse AP1000 export deal had basically JUST been signed at this point. The first unit at Sanmen wasn't even under construction yet. This was a wild time...there were dozens of AP1000s sites all across China being planned all at once.

sxb.nea.gov.cn/dtyw/hyxx/2023…

The first mention I can find of it goes back to 2007, when Guodian (one of the plant owners) set up a Project Office in Zhangzhou.

We learn from this very early notice that the site plans to use AP1000 reactors imported from Westinghouse. Keep in mind, the Westinghouse AP1000 export deal had basically JUST been signed at this point. The first unit at Sanmen wasn't even under construction yet. This was a wild time...there were dozens of AP1000s sites all across China being planned all at once.

sxb.nea.gov.cn/dtyw/hyxx/2023…

In March 2009, the Guodian Zhangzhou Project Office publishes its first public consultation notice. It has contracted the Shanghai Nuclear Engineering Research and Design Institute (SNERDI) to do an environmental impact assessment report for the site selection phase.

We learn that they plan to pour concrete in August 2011 on the first of six reactors, across two phases, with grid connection targeted for August 2016.

hbj.zhangzhou.gov.cn/cms/siteresour…

We learn that they plan to pour concrete in August 2011 on the first of six reactors, across two phases, with grid connection targeted for August 2016.

hbj.zhangzhou.gov.cn/cms/siteresour…

By August 2009, the second public consultation letter is issued, summarizing the results from the environmental impact assessment and feasibility report, which both point to the site's suitability for a nuclear power plant with at least 4 AP1000 reactors.

hbj.zhangzhou.gov.cn/cms/siteresour…

hbj.zhangzhou.gov.cn/cms/siteresour…

Following a Project Site Suitability Assessment Meeting in December 2010, China's Nuclear Energy Association announces that the site selection phase is "basically complete", and Guodian will now proceed to pre-construction work (site leveling, connecting utilities, etc.)

china-nea.cn/site/content/2…

china-nea.cn/site/content/8…

china-nea.cn/site/content/2…

china-nea.cn/site/content/8…

In March, 2011, the earthquake, tsunami and subsequent nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan derail everything. All site approvals are frozen and construction work at all Chinese sites is halted. Incidentally, I have just arrived in Beijing for my study abroad in college. I see the accident on the news.

At the end of 2011, the CNNP Guodian Zhangzhou Energy Company is formally established, with Guodian as the minority shareholder (49%) to CNNC (51%). Clearly they are expecting to move ahead with this project, even if things are stalled for the moment.

tianyancha.com/company/274659…

At the end of 2011, the CNNP Guodian Zhangzhou Energy Company is formally established, with Guodian as the minority shareholder (49%) to CNNC (51%). Clearly they are expecting to move ahead with this project, even if things are stalled for the moment.

tianyancha.com/company/274659…

Everything stays frozen in place for about 2 years, across most the industry. The NEA/NNSA are trying to figure out how to proceed. Nobody is building anything.

Nothing nuclear anyway. In 2013, CNNP Guodian Zhangzhou Energy Company, perhaps out of pure boredom, goes ahead and builds the 20 MW Qingjing offshore wind farm, just off the coast of their stalled nuclear power plant.

Nothing nuclear anyway. In 2013, CNNP Guodian Zhangzhou Energy Company, perhaps out of pure boredom, goes ahead and builds the 20 MW Qingjing offshore wind farm, just off the coast of their stalled nuclear power plant.

Things start moving again at the end of the year though. In November 2013, the NEA gives Zhangzhou approval to go ahead with preliminary site work. In August 2014, a new environmental impact report is released for public comment (I suppose the report was redone following Fukushima).

Also in August 2014, the Ministry of Land and Natural Resources grants formal approval for the land to be used for a nuclear power plant.

cnnp.com.cn/cnnp/cydwzd62/…

news.ijjnews.com/system/2014/08…

cnnp.com.cn/cnnp/zyyw73/yw…

Also in August 2014, the Ministry of Land and Natural Resources grants formal approval for the land to be used for a nuclear power plant.

cnnp.com.cn/cnnp/cydwzd62/…

news.ijjnews.com/system/2014/08…

cnnp.com.cn/cnnp/zyyw73/yw…

Not much news in 2015 - China Energy Net reports that the project is now in its "initiation stage" and the project owner submits its Phase 1 Facilities Safety Analysis Report to the national regulator for review.

At this point, the site is STILL supposed to be 6 AP1000s.

At this point, the site is STILL supposed to be 6 AP1000s.

A bombshell arrives in January 2016, when CNNC, Guodian, and the Fujian Development and Reform Commission formally petition the NEA to allow them to change their site to use domestic Hualong One reactor technology, instead of the long-planned AP1000s.

At this point, the Hualong One is under construction at two sites in Fujian and Guangxi, respectively, with no operating reference reactor. The AP1000 is under construction at two sites in Zhejiang and Shandong, respectively, also with no operating reference reactor.

The reactor change application is approved in October 2016, when Zhangzhou Units 1 and 2 are formally cleared by the NEA and NDRC to move ahead building Hualong One reactors. A construction date is not set.

At this point, the Hualong One is under construction at two sites in Fujian and Guangxi, respectively, with no operating reference reactor. The AP1000 is under construction at two sites in Zhejiang and Shandong, respectively, also with no operating reference reactor.

The reactor change application is approved in October 2016, when Zhangzhou Units 1 and 2 are formally cleared by the NEA and NDRC to move ahead building Hualong One reactors. A construction date is not set.

Chinese media The Paper summarizes the situation:

"Zhangzhou was originally planning to build AP1000 PWRs imported from the United States. The AP1000 is an advanced, passively safe PWR technology imported from the USA's Westinghouse, with the construction of the world's first plant at Sanmen in Zhejiang Province beginning in March 2009. The project has been delayed due to a series of difficulties in design, manufacturing, and construction that arose in the course of this first-of-a-kind reactor. This poor progress has also blocked the approval of subsequent AP1000 projects, of which the Zhangzhou project was one. In January 2016, CNNC, Guodian, and the Fujian DRC jointly submitted a letter to the NEA to change the plant to the Hualong One technology path."

m.thepaper.cn/kuaibao_detail…

"Zhangzhou was originally planning to build AP1000 PWRs imported from the United States. The AP1000 is an advanced, passively safe PWR technology imported from the USA's Westinghouse, with the construction of the world's first plant at Sanmen in Zhejiang Province beginning in March 2009. The project has been delayed due to a series of difficulties in design, manufacturing, and construction that arose in the course of this first-of-a-kind reactor. This poor progress has also blocked the approval of subsequent AP1000 projects, of which the Zhangzhou project was one. In January 2016, CNNC, Guodian, and the Fujian DRC jointly submitted a letter to the NEA to change the plant to the Hualong One technology path."

m.thepaper.cn/kuaibao_detail…

Things go quiet again for 2 years. No new reactors can begin construction until it looks like their reference plants are completed. Zhangzhou Units 1 and 2 are considered the demonstration units for "Hualong One batch construction".

In October 2018, they are given a construction start date of October 2019, with planned grid connection in June 2024.

cnnp.com.cn/cnnp/zyyw73/yw…

In October 2018, they are given a construction start date of October 2019, with planned grid connection in June 2024.

cnnp.com.cn/cnnp/zyyw73/yw…

On October 17, 2019, Zhangzhou Unit 1 pours its first barrel of safety-related concrete (First Concrete Date, or FCD). Construction!

It has taken nearly 10 years to get to this point, although to be fair, a lot of time was spent waiting and duplicating work previously completed...

It has taken nearly 10 years to get to this point, although to be fair, a lot of time was spent waiting and duplicating work previously completed...

From this point on, China demonstrates what it does better than anyone else: building really big, really expensive, really complex infrastructure, really goddamn fast.

One year later (November 3, 2020) all sub-surface work is completed.

cnnc.com.cn/eportal/ui?pag…

One year later (November 3, 2020) all sub-surface work is completed.

cnnc.com.cn/eportal/ui?pag…

The Zhangzhou company chairman is quoted in local news saying that most of his 10,000 construction employees opted to remain on the site and work through the early stages of the pandemic, rather than go home for the Chinese New Year in spring 2020. That's...a lot of people.

In April 2021, The Paper does a feature on Zhangzhou's metalworking team leader, Mr. Zhang Guobin, a 37-year construction veteran with 13 years of nuclear metalworking experience across 3 sites. He manages of an onsite team of 80 people who do nothing but bend and shape metal for Zhangzhou.

He says at the start of the project, he had just 12 guys, so they had to work 12-hour relay shifts to keep production going 24/7, but things are a little more relaxed now as the team has grown.

m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_1243…

He says at the start of the project, he had just 12 guys, so they had to work 12-hour relay shifts to keep production going 24/7, but things are a little more relaxed now as the team has grown.

m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_1243…

By August 201, the concrete pours for the internal structure of Unit 1 are complete. From the outside, the progress is rapid and visible. Unit 1 is on the left. The containment steel liner is being assembled nearby.

On October 27, 2021, the steel containment liner is lifted and installed into place.

baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=171477488…

baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=171477488…

No major milestones are achieved for a while (although may smaller ones are hit).

The next big news comes in June 2022, when the containment shell steel pre-tensioning work is completed.

The next big news comes in June 2022, when the containment shell steel pre-tensioning work is completed.

On February 17, 2023, the containment building is "capped off" with the top module lifted and dropped into place. At this point, the NSSS equipment has already been dropped in and civil construction is mostly finished.

We are now into the installation and testing/inspection phase, and most of the work is internal. From the outside, the plant looks mostly complete.

news.cn/fortune/2023-0…

We are now into the installation and testing/inspection phase, and most of the work is internal. From the outside, the plant looks mostly complete.

news.cn/fortune/2023-0…

In November 2023, the "cold testing" at Zhangzhou 1 is complete and the plant is considered to have exited the installation phase and now entered the "comissioning" phase.

caea.gov.cn/n6760338/n6760…

caea.gov.cn/n6760338/n6760…

The next big task/milestone was "hot testing", which took about 6 months and finished in May 2024.

sthjt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/ywxx/hyj/…

sthjt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/ywxx/hyj/…

...and that cleared the way for the first loading of uranium fuel. The regulator approved Zhangzhou's first fuel load on October 13, 2024.

This is basically them saying "load your fuel and proceed as you like". It's an operations permit.

finance.people.com.cn/n1/2024/1013/c…

This is basically them saying "load your fuel and proceed as you like". It's an operations permit.

finance.people.com.cn/n1/2024/1013/c…

Following that, the plant smoothly moved to first criticality, first power output, and grid connection by the end of November 2024.

After 168 hours (7 days) it will be declared "fully commercially operational".

Zhangzhou 2 (on the right) is about 6-12 months behind.

After 168 hours (7 days) it will be declared "fully commercially operational".

Zhangzhou 2 (on the right) is about 6-12 months behind.

So what's the secret? Clearly China doesn't have a shorter pre-construction cycle compared to other countries around the world.

If anything, it's longer, more tedious, and even MORE bureaucratic than its peers. Hopefully Zhangzhou is an outlier, because 10 years is brutal!

If anything, it's longer, more tedious, and even MORE bureaucratic than its peers. Hopefully Zhangzhou is an outlier, because 10 years is brutal!

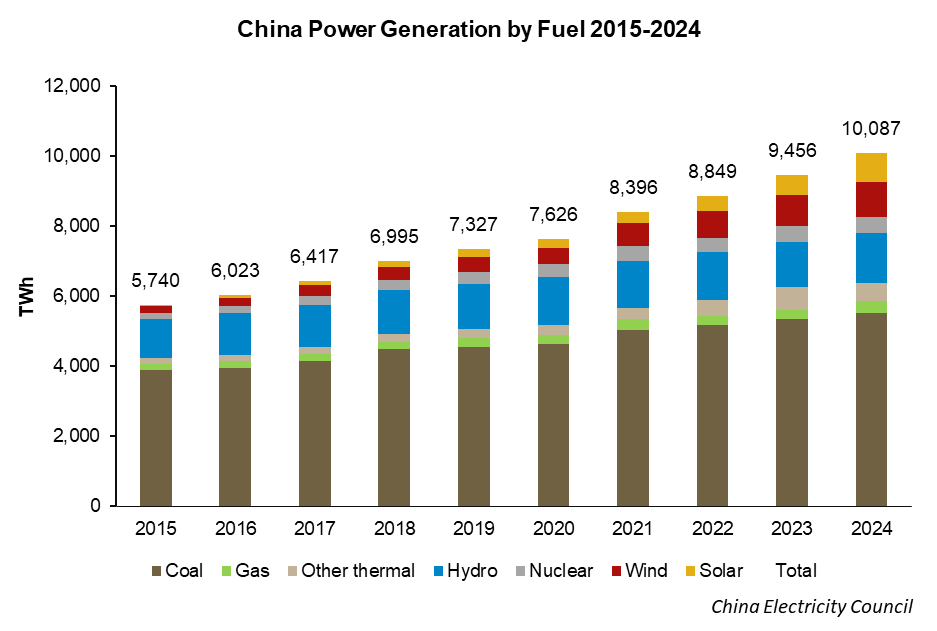

Even if you don't understand nuclear development at all, you should be able to identify the Construction and Installation phases of Zhangzhou 1 as Extremely Goddamn Fast.

They went from a leveled site to a complete shell in less than 36 months, with the major work in 24.

They went from a leveled site to a complete shell in less than 36 months, with the major work in 24.

When you borrow USD 5B to build these things. the interest is insane. Time is literally money. Even at very favorable interest rates, every single day over the construction schedule is a million dollars of interest...and a million dollars of lost power sales.

China builds these things by throwing 10,000 people at the program, like ants coming together to move an elephant. There probably a dozen different construction companies onsite at any single time (often sister companies or subsidiaries of the project owner).

Every skilled laborer onsite has been doing this job, and just this job, for years, maybe decades. And yeah, they'll do a 12-hour 2-man relay to ensure 24h production of metal parts...

Every team leader, every shift boss, is a veteran of multiple recent reactor builds...

Every team leader, every shift boss, is a veteran of multiple recent reactor builds...

If there are issues during installation or comissioning...the manufacturer is in the indutrial park down the street, or in the neighboring province. They'll prototype a new part, iterate it a few times, and get you the fixed piece shipped to the site within weeks, or days...

You can blame the NRC for hamstringing the US industry, and demand they streamline your regulatory processes and approvals, speed up permitting, remove red tape...all you like...China also has these headaches.

It'll help. But unless also you have workers and producers and team leaders able to do all of what I just described, you aren't going to build nuclear power plants in 62 months like China is, and will continue to do.

At a pace of 8-10 per year. For the next 3 decades.

It'll help. But unless also you have workers and producers and team leaders able to do all of what I just described, you aren't going to build nuclear power plants in 62 months like China is, and will continue to do.

At a pace of 8-10 per year. For the next 3 decades.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh