Americans consume so much healthcare that they don't need.

As it turns out, this is true in a lot of places, and we have excellent evidence that's the case.

Thread.

As it turns out, this is true in a lot of places, and we have excellent evidence that's the case.

Thread.

Britain has universal healthcare via their National Health Service.

In this system, the doctors are paid very poorly. Junior doctors—known as "resident doctors" since September of this year—have gone on strike about this several times in recent years.

In this system, the doctors are paid very poorly. Junior doctors—known as "resident doctors" since September of this year—have gone on strike about this several times in recent years.

In 2016, a dispute between the government and medical unions about new junior doctor contracts came to a head and the junior doctors didn't like the terms they were offered.

So, five strikes took place across all English public hospitals between January and April of that year.

So, five strikes took place across all English public hospitals between January and April of that year.

During the protests, the vast majority of junior doctors did not report for duty.

As a result, more than 100,000 outpatient appointments and more than 25,000 fewer planned admissions had to be canceled.

Senior doctors and nurses also had to be redeployed to emergency services.

As a result, more than 100,000 outpatient appointments and more than 25,000 fewer planned admissions had to be canceled.

Senior doctors and nurses also had to be redeployed to emergency services.

Hospitals acted to mitigate the impacts of the strikes, requiring some of the junior doctors on roster for emergency services to stay out, calling freelance locum doctors into the NHS, canceling holidays and study leave for staff groups, and asking private doctors for help.

But this wasn't enough to save the NHS' volume, and the backlog of appointments the strike generated was vast.

The strike reduced emergency arrivals and admissions, as well as elective admissions considerably:

The strike reduced emergency arrivals and admissions, as well as elective admissions considerably:

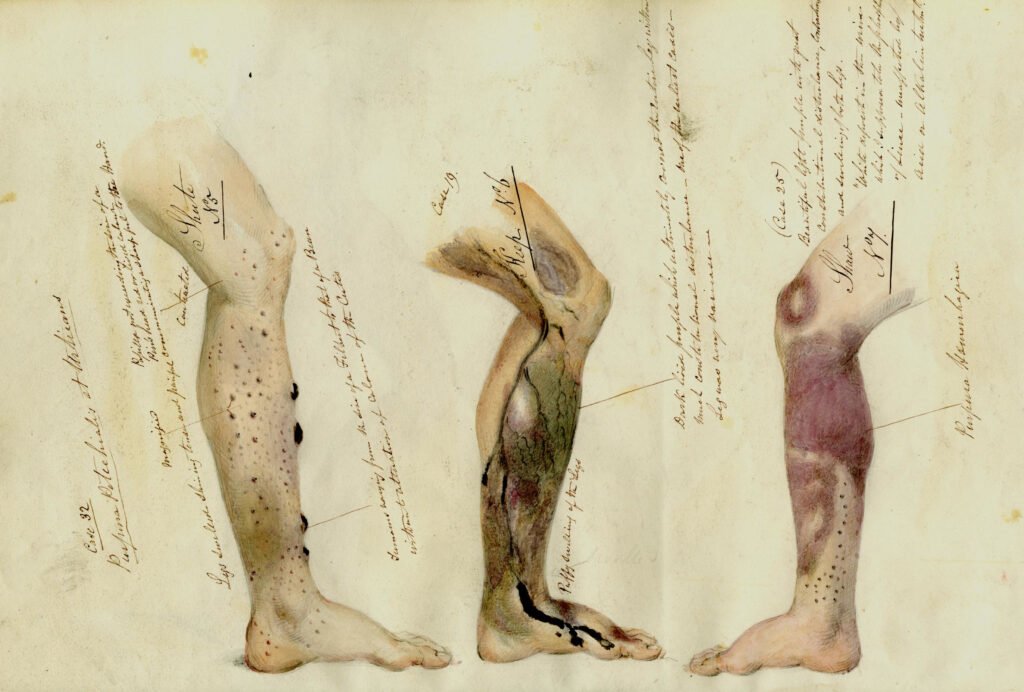

When the strikes took place, patients who still came in had different characteristics, meaning still going to the hospital on a day where there were fewer doctors available was selective.

Go ahead and read these to see how. For reference, Charlson Score is a comorbidity index:

Go ahead and read these to see how. For reference, Charlson Score is a comorbidity index:

Given elective patients were older, emergency ones were younger, etc., a strategy to identify the impacts the strike had on patients given the reduced volume of care caused isn't obvious

So, these authors leveraged the proportion of junior docs at a hospital as an exposure index

So, these authors leveraged the proportion of junior docs at a hospital as an exposure index

Taking this interaction out, the impact of strikes on patient characteristics is no longer significant, and that result is precise enough with small enough coefficients that we're probably fine to go ahead with using this instrument.

So let's check: What happens to patients when they're heavily exposed to a strike?

In terms of readmissions within 30 days and mortality... nothing, not even when you stratify by exposure level or control for the severity of patient condition!

In terms of readmissions within 30 days and mortality... nothing, not even when you stratify by exposure level or control for the severity of patient condition!

The volume of care provided by the NHS is reduced by strikes, but not so much that patients are harmed.

That means there's unnecessary care happening.

This study's conclusions, by the way, are not unique. There's actually a large literature on the effects of doctor strikes.

That means there's unnecessary care happening.

This study's conclusions, by the way, are not unique. There's actually a large literature on the effects of doctor strikes.

In 2008, Cunningham et al. provided a review, in which they noted that doctor strikes with variables lengths, participation, and so on, from Jerusalem to Los Angeles had similar non-effects, or even potentially positive effects on patient mortality!

The amount of care people consume might not just be so high it's wasteful, but so high it's harmful.

Meta-analytically, the impact of doctor strikes all the way through 2021 seems to be... bupkes. It just doesn't matter when doctors go on strike.

Meta-analytically, the impact of doctor strikes all the way through 2021 seems to be... bupkes. It just doesn't matter when doctors go on strike.

This finding holds up in low-middle income countries, for strikes that happen for nurses and other staff too, across many sites, and even up to 250 days of striking in one study.

Care volumes are definitely affected, appointments are missed, prescription numbers decline, etc.

Care volumes are definitely affected, appointments are missed, prescription numbers decline, etc.

And yet, people carry on, and maybe even get a little better off.

Now there's obviously important care doctors need to be there to provide, but most of the time people are visiting the doc, it's just not providing them or the healthcare system any value: It's payment for nothing

Now there's obviously important care doctors need to be there to provide, but most of the time people are visiting the doc, it's just not providing them or the healthcare system any value: It's payment for nothing

There are a lot of other ways we can see that people consume too much care, aided by plenty of different designs, like RCTs comparing more and less extensive screening protocols.

But to some extent, it should be obvious that people consume too much healthcare that's way too low-value.

Consider @robinhanson's explanation for a variety of stylized facts about overprovisioning of care, to explain why it's a superior good:

Consider @robinhanson's explanation for a variety of stylized facts about overprovisioning of care, to explain why it's a superior good:

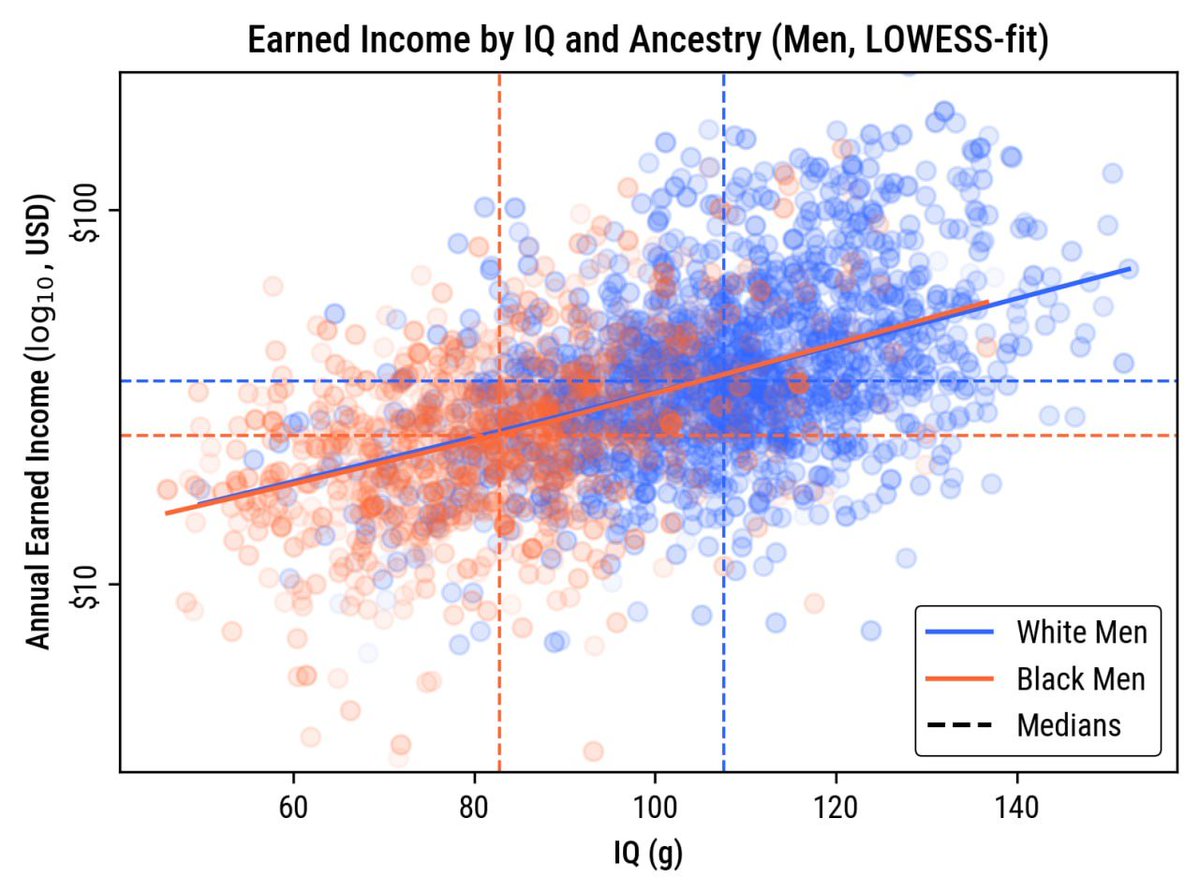

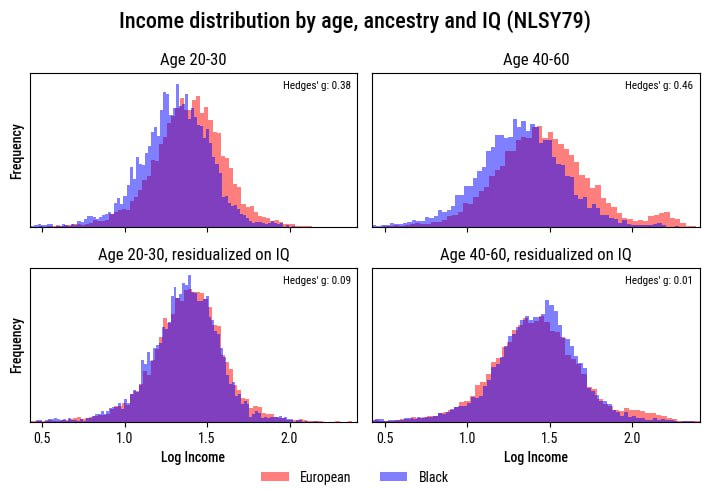

You can also look at simpler data to see this, like the data showing that the health share of consumption does rise very rapidly with income, and thus the reason the U.S. spends so much on healthcare is primarily because it's very rich.

Relatedly, if you take a look at health expenditures per capita versus life expectancies, you actually see evidence of nonlinearities, such that past some level of spending, the superior good status of healthcare gets ugly because it stops generating returns.

We can go on, talking about ineffective but common treatments, overprovided medicines and overly long therapies and surgeries, and more, but I think my point is clear:

People consume too much healthcare, and it doesn't benefit them to do so.

To cut costs, they could spend less.

People consume too much healthcare, and it doesn't benefit them to do so.

To cut costs, they could spend less.

If you want to see a country like America cut its costs, you can eliminate all the inefficiencies, and then you'll still have to deal with the fact that Americans consume too much healthcare.

How much? I think Hanson and Cutler are right, at about 30-50% and increasingly more.

How much? I think Hanson and Cutler are right, at about 30-50% and increasingly more.

Oh and this is the vital role of insurers in the healthcare system: they are the hidden rationers that keep it running.

Sources:

mercatus.org/students/resea…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/14…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

randomcriticalanalysis.com/2019/11/07/a-t…

Sources:

mercatus.org/students/resea…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/14…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

randomcriticalanalysis.com/2019/11/07/a-t…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh