Hardly any of Ancient Rome's great wonders still stand today — they were lost to the Middle Ages.

But why couldn't medieval people recreate, or even maintain what the Romans had built?

An ancient technology had been long forgotten… (thread) 🧵

But why couldn't medieval people recreate, or even maintain what the Romans had built?

An ancient technology had been long forgotten… (thread) 🧵

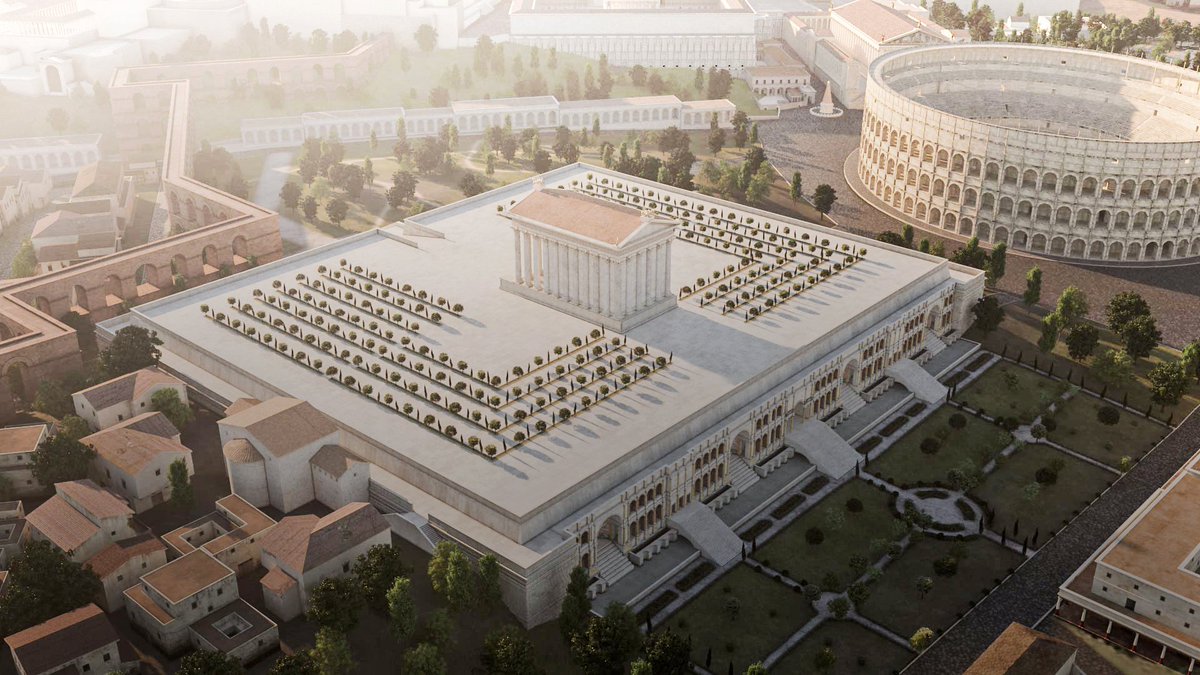

When you see reconstructions of Imperial Rome you have to wonder where it all went — a city of 1 million people with immense infrastructure.

How exactly was so much lost?

How exactly was so much lost?

Take the Forum of Nerva — it reverted to marshland after the Western Roman Empire fell, and simple houses squatted inside it for centuries as it crumbled.

Today, nothing remains but its foundations.

Today, nothing remains but its foundations.

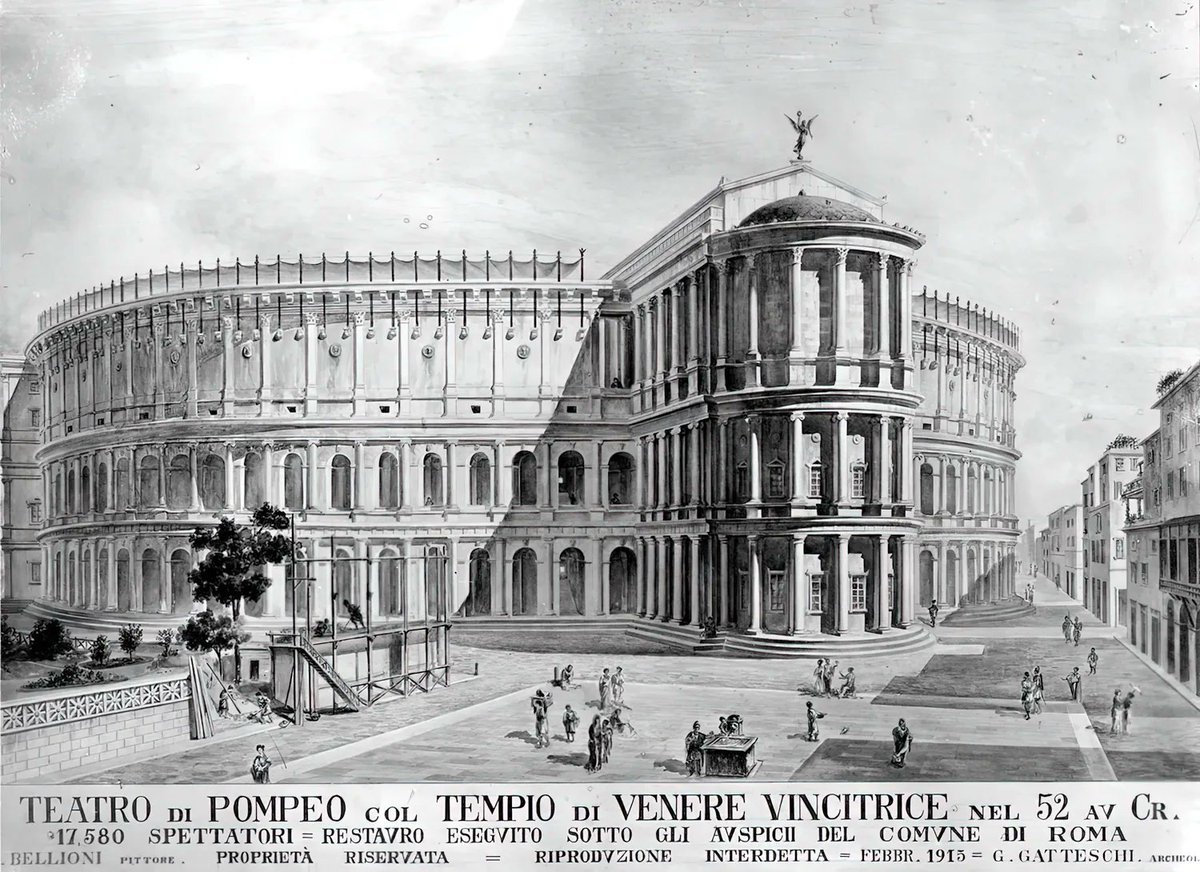

Other imperial wonders were lost entirely. The Temple of Claudius, gloriously restored by Vespasian in the 1st century, was in ruins a few centuries later...

Why exactly?

Why exactly?

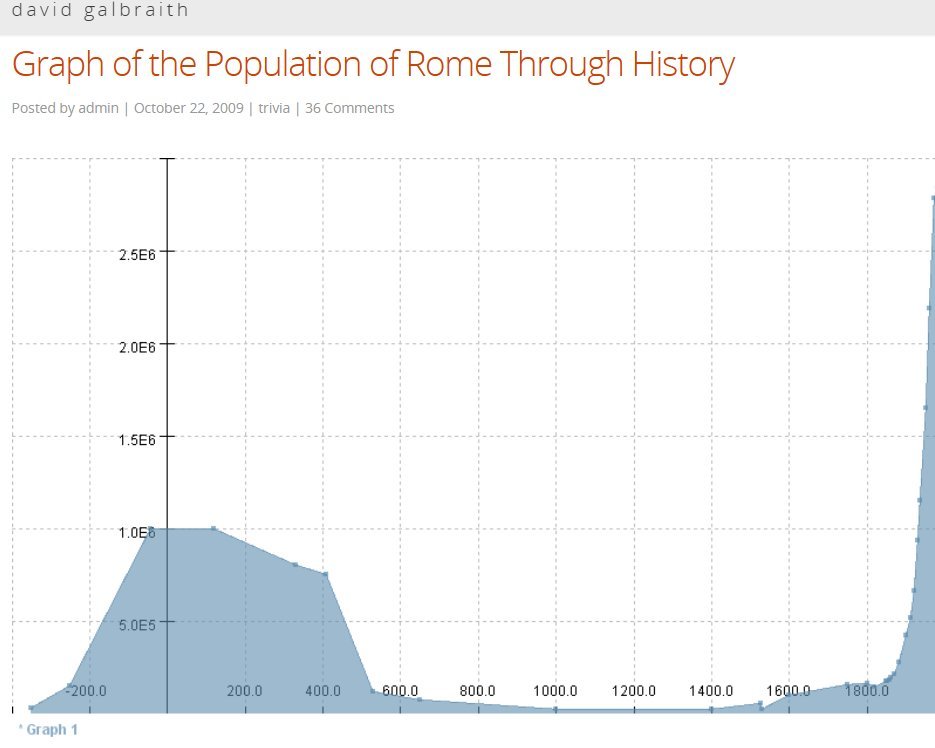

The main culprit: population collapse.

Urban populations cratered as the empire fell. 800,000 people lived in Rome before the sack of 410 AD — fewer than 30k were left by 600 AD.

Urban populations cratered as the empire fell. 800,000 people lived in Rome before the sack of 410 AD — fewer than 30k were left by 600 AD.

Rome at its peak relied on huge quantities of imports like grain and fuel from across the empire.

When transport links broke down, imported grain that fed the city and firewood that kept its baths warm disappeared...

When transport links broke down, imported grain that fed the city and firewood that kept its baths warm disappeared...

So urban centers like Rome, unable to support large populations, had little use for grand baths and arenas.

They were abandoned to the elements, rocked by earthquakes, and their marble pillaged to make lime.

They were abandoned to the elements, rocked by earthquakes, and their marble pillaged to make lime.

Or, they were picked apart for building materials.

The Colosseum was plundered for its valuable travertine — a single quarryman once took 2,522 cartloads of it in 1452.

The Colosseum was plundered for its valuable travertine — a single quarryman once took 2,522 cartloads of it in 1452.

Most buildings were left as rubble not because they couldn't rebuilt them — they simply had no reason to.

However, some things were impossible for medieval people to recreate...

However, some things were impossible for medieval people to recreate...

The Pantheon is one. It was the result of a technology almost completely unknown in medieval Europe: concrete.

And the Romans had a remarkable ancient recipe...

And the Romans had a remarkable ancient recipe...

The Pantheon has stood for 2,000 years and is *still* the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome.

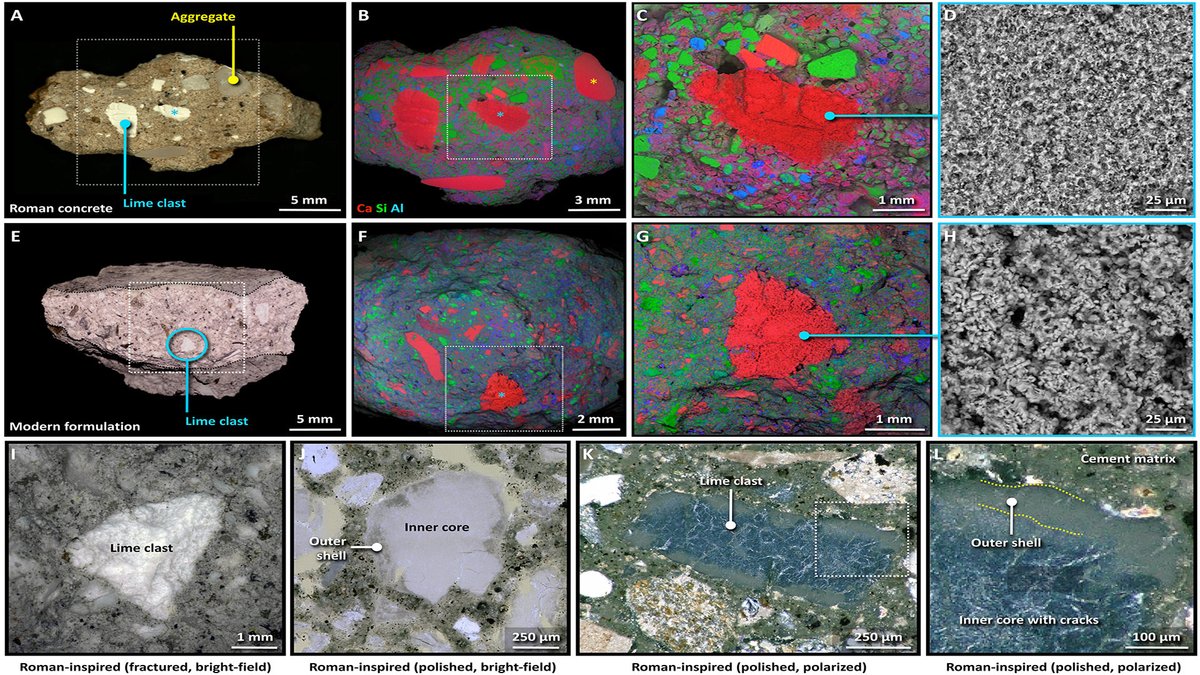

In 2022, new research finally revealed why it lasted so long — Roman concrete contains quicklime, which allows it to "self-heal"...

In 2022, new research finally revealed why it lasted so long — Roman concrete contains quicklime, which allows it to "self-heal"...

These calcium carbonate lumps called "lime clasts" were previously thought to be due to poor mixing.

We now know that water seeping in through cracks in the concrete dissolves the calcium carbonate, forming a solution which then recrystallizes to plug the gaps.

We now know that water seeping in through cracks in the concrete dissolves the calcium carbonate, forming a solution which then recrystallizes to plug the gaps.

When the empire declined and monumental construction projects no longer commissioned, concrete became irrelevant.

People reverted to brick and wood, and the ancient formula was lost to time.

People reverted to brick and wood, and the ancient formula was lost to time.

But the loss of Rome's imperial treasures is less a story of technical ability, more what was chosen to be saved.

The Pantheon survived because it was converted to a church in 609 AD, and effort spent to maintain it.

The Pantheon survived because it was converted to a church in 609 AD, and effort spent to maintain it.

Besides, medieval Christians built from the rubble a new set of Roman wonders.

Repurposed stones became great fountains instead of baths, and churches instead of temples...

Repurposed stones became great fountains instead of baths, and churches instead of temples...

If you enjoy threads like this, I go deeper in my FREE newsletter.

Do NOT miss tomorrow's email!

98,000+ people read it: history, art and culture 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

Do NOT miss tomorrow's email!

98,000+ people read it: history, art and culture 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh