Fantastic review on chronic SARS-CoV-2 infections by virological superstars Richard Neher & Alex Sigal in Nature Microbiology. I’ll do a short overview, outline a couple minor quibbles, & defend the honor of ORF9b w/some stats & 3 striking sequences from the past week.

1/64

1/64

First, let me say that this is well-written, extremely readable, and accessible to non-experts, so you should go read the full paper yourself, if you can find a way to access it. (Just realized it’s paywalled, ugh.) 2/64nature.com/articles/s4157…

Neher & Sigal focus on the 2 most important aspects of SARS-CoV-2 persistence: its relationship to Long Covid (including increased risk of adverse health events) & its vital importance to the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants. I’ll focus on the evolutionary aspects.

3/64

3/64

They divide persistent infections into 2 categories, based on immune status of the host: immunocompromised (IC) or immunocompetent. There are of course intermediate immune states—immunosenescent the most important example to me—but the binary model is the most useful model.

4/

4/

Chronic SARS-2 infections in the IC are exceedingly well documented. In one sense, this isn't abnormal: chronic infections in IC have been documented for many “short infection” viruses—influenza, parainfluenza, rhinoviruses, adenoviruses, “common-cold” CoVs, norovirus, etc.

5/

5/

What makes chronic SARS-CoV-2 infections different? One difference is the way such long-term infections have dominated the evolution of major variants. Nothing like this is known to happen w/other human viruses (though can't be definitively ruled out due to spotty sequencing.

6/

6/

Prolonged influenza infections in the IC, for example, have been documented, but there is no sign they’ve ever led to major flu variants. This prompts 2 questions:

1) Why do major SARS-2 variants arise from chronic infections?

2) Why not in other viruses?

1) Why do major SARS-2 variants arise from chronic infections?

2) Why not in other viruses?

https://x.com/trvrb/status/1487231618754363394

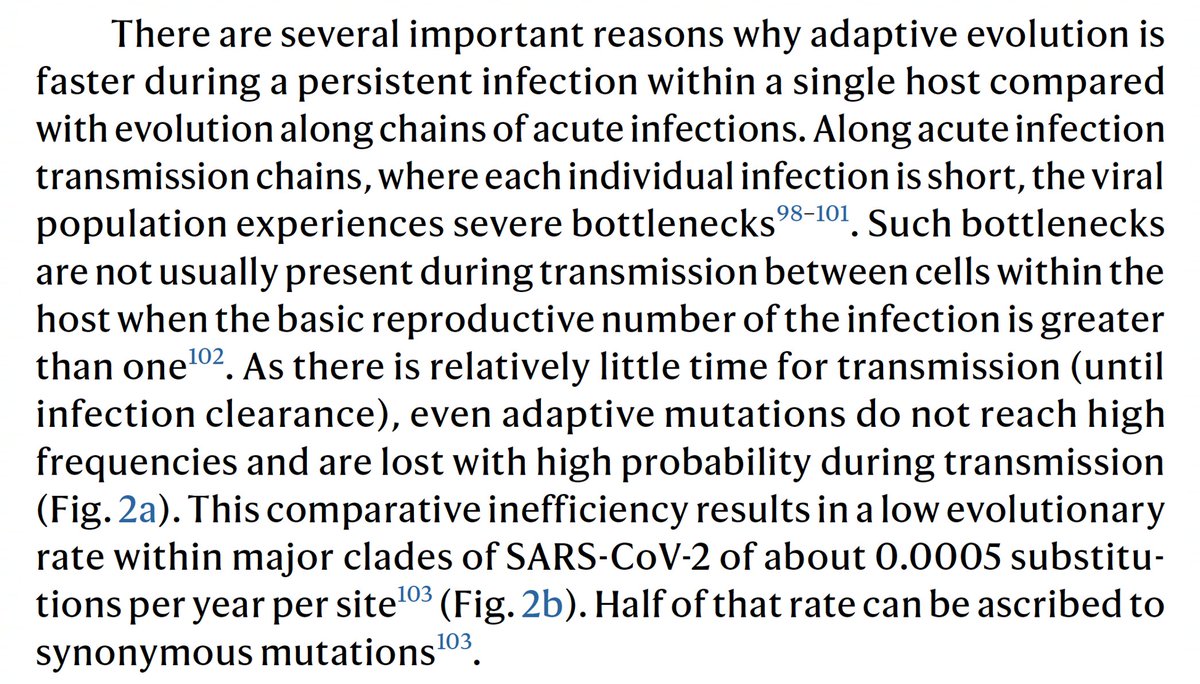

One major reason chronic infections have created variants is the lack of a transmission bottleneck, which I’ve discussed previously (e.g. posts 6-11 in thread below). Neher & Sigal also write about this.

8/

8/

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1781121835607748969

Another possible explanation for the success of chronic infection-derived variants is that the adaptive immune response takes time to kick in—after the period of transmission in many/most cases—it is in long-term infections that antibody-escape mutations evolve efficiently.

9/64

9/64

The long branches leading to new, chronic infection-derived variants exhibit more rapid evolution than circulating lineages, and, as outlined in the paper, many studies of infections in the immunocompromised have directly observed the same.

10/

10/

It’s important to recognize that the vast, vast majority of chronic infections do not lead to serious variants; in fact, it seems they rarely transmit at all, for unknown reasons, even when they possess potent immune evasion (see 1 hypothesis below).

11/

11/

https://x.com/Nucleocapsoid/status/1771873048657859028

There are thousands of examples of such chronic-infection sequences, and each sequence undoubtedly represents hundreds of similar, unsequenced potential variants. Neher/Sigal outline numerous studies that hint at the enormous number of hidden, long-term infections.

12/64

12/64

It’s not at all clear why a tiny fraction of these highly mutated variants transmit widely and others do not. But the success of such variants was not, as far as I know, predicted by anyone, and this was not just because there were no clear previous examples.

13/

13/

There are good theoretical & empirical reasons these variants were unexpected. I haven’t read a similar discussion of this elsewhere, so this is one of the highlights of the paper to me. One example: ancestral HIV variants transmit more successfully host-adapted ones.

14/

14/

Many mutations in chronic seqs seem to fit this description, like E:T30I & M:H125Y. Many dozens of others that almost never transmit are reversions to Bat-CoV residues & likely adaptations to the GI tract that impede transmission. See @SolidEvidence for more on this.

15/

15/

There are innumerable way to be immunocompromised—inherited genetic disorders, immunosuppressive therapies, cancer, etc—but advanced HIV may be an especially potent incubator of potential variants & may explain why so many have originated in Southern Africa. 16/64

Many people suffering chronic infections are very sick: the metadata from sequences very often indicates hospitalization. Others, aware of their vulnerability to infection, have few social contacts and/or mask in social situations. But HIV is often very different.

17/

17/

Many people with advanced HIV who are chronically infected with SARS-CoV-2 have few or no symptoms & therefore have a normal number of social contacts.

18/

18/

Furthermore, intermittent use of antiretrovirals (ARVs) could periodically subject the virus to enough antibodies to foster escape mutations but not enough to clear the virus entirely.

19/

19/

Speculatively, perhaps 99% is cleared but a reservoir in the GI tract or other tissue persists, that later, when ARV treatment lapses, expands to the respiratory tract & potentially transmits. There is indirect evidence for this that requires a look at Bat-CoVs & Cryptics.

20/

20/

I don’t think transmission in bats is well characterized, but it seems CoVs preferentially infect GI tissue in bats. Tissue tropism of one Merbecovirus was analyzed & found to favor GI tissue in a paper by @thijskuiken, @MarionKoopmans, & @VeraMols

21/64

journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jv…

21/64

journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jv…

There are a striking number of mutations in major variants that are “reversions” to AA residues in Bat-CoVs. Gamma’s ORF1a:K1795Q, as @SolidEvidence first pointed out, is one example. BA.2.86 possesses a panoply of such mutations.

22/64

22/64

https://x.com/SolidEvidence/status/1772329053422490078

This at least suggests the possibility that some major variants spent extensive time evolving in the GI tract of the chronically infected individual they evolved in.

Two remarkable chronic-infection sequences also hint at a possible GI-to-lung transition.

23/64

Two remarkable chronic-infection sequences also hint at a possible GI-to-lung transition.

23/64

The Cryptics documented by @SolidEvidence bear some distinct mutational signatures that almost never appear in conventional nasal-swab sequences. One is S:L828F.

24/64

24/64

https://x.com/SolidEvidence/status/1652404081405591552

One of the most remarkable seqs ever was from the lab of @GBazykin: a B.1.1 collected in Oct 2022 whose closest relatives were collected around July-Sept 2020. It had many distinctive Cryptic mutations—but not S:L828F.

25/64

25/64

https://x.com/GBazykin/status/1704761828415590808

BUT, it very clearly *had* S:L828F at some previous time, and I think this likely represents the virus’s transition from the lungs, to the GI tract, and back again. See posts #13-19 below for my previous explanation of this.

26/

26/

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1770561720081174692

Another mutation that’s even rarer than S:L828F—& which appears almost exclusively in long-term, highly mutated chronic infections—is S:L1186F. Though it’s uncommon in Cryptics, it sometimes appears with very rare Cryptic-type mutations like… 27/

…the ORF1b:L314P reversion & S:Q498H, (both of which are in the B.1.1 sequence described above & in many Bat-CoVs). Two remarkable chronic BA.5.2 seqs from Canada did not have S:L1186F. 28/

BUT, like L828F in the B.1.1 sequence discussed above, they clearly had S:L1186F previously. C25118T is in every S:L1186F sequence ever. C25120A causes the F1186L AA reversion, but leaves a tell-tale trace in the genomic record. 29/

There are only a few dozen S:L1186F sequences ever, with close to half clear chronics. It’s may be meaningful that 3 are labeled as having come from bronchoalveolar lavage. Perhaps an inability to thrive in the URT prevents L1186F from transmitting.

30/

30/

Interesting tidbit: in chronics there’s a very tight connection between mutations at E:5-42 (esp ∆V14 & T30I) & a region of NSP4 (ORF1a:3049-3089 plus—oddly—ORF1a:2972).

*All* S:L1186F chronics have ≥1 mut at E:5-36 and 8/11 have ≥1 in the NSP4 region.

31/64

*All* S:L1186F chronics have ≥1 mut at E:5-36 and 8/11 have ≥1 in the NSP4 region.

31/64

Back to the paper. I have a few tiny quibbles, one involving non-spike muts in chronics, particularly ORF9b mutations. Sigal/Neher state that “mutations are not often observed outside spike” in chronics and note that “Mutations in ORF9b, ORF6, and N, key viral proteins…

32/64

32/64

…which mediate escape from innate immunity, do not appear in the list of mutations from persistent infections.” The list is based on 3 great studies by

@Mahan_Ghafari, @LucaFerrettiEvo, @jcbarret;

@sigallab, @farinakarim, @tuliodna;

@PeacockFlu, @pathogenomenick

33/

@Mahan_Ghafari, @LucaFerrettiEvo, @jcbarret;

@sigallab, @farinakarim, @tuliodna;

@PeacockFlu, @pathogenomenick

33/

…& it’s a good list, but, I’d argue, incomplete. Using several thousand chronic seqs I’ve documented I’ve tried to calculate the rate of private mutations per AA residue for various proteins. It’s an imperfect measure but I think broadly accurate.

34/

34/

In raw counts, ORF9b ranks #1. An adjusted version that excludes mutations that are clearly not overrepresented in chronic sequences puts spike first, followed by E, then ORF9b. I need to improve this measure further by adjusting for mutation rates in circulating sequences.

35/

35/

As I noted in a previous thread, ORF9b is coded from an internal, overlapping reading frame within the N gene. Eddie Holmes & @SimonLoriereLab have noted that mutation rates tend to be lower in overlapping genes—especially internal ones like ORF9b.

36/64

36/64

But ORF9b is not just an overlapping gene; it’s also a fold-switching protein. Remarkably, it takes on two completely different protein structures: a monomer whose ordered regions are all alpha helices & a dimer consisting entirely of beta strands.

37/64

37/64

I’ll eventually finish a thread/paper elaborating a bit on this, but briefly, the ORF9b monomer powerfully antagonizes the IFN response while the dimer holds a lipid molecule & likely plays an important role in assembly. See great work by @KroganLab & @DoctorBou on this.

38/64

38/64

Considering this, the very high mutation rate in ORF9b is very surprising: Not only are ORF9b’s mutational options severely limited because it shares a frame with N, it also has to preserve two structural forms, which carry out entirely different functions.

39/64

39/64

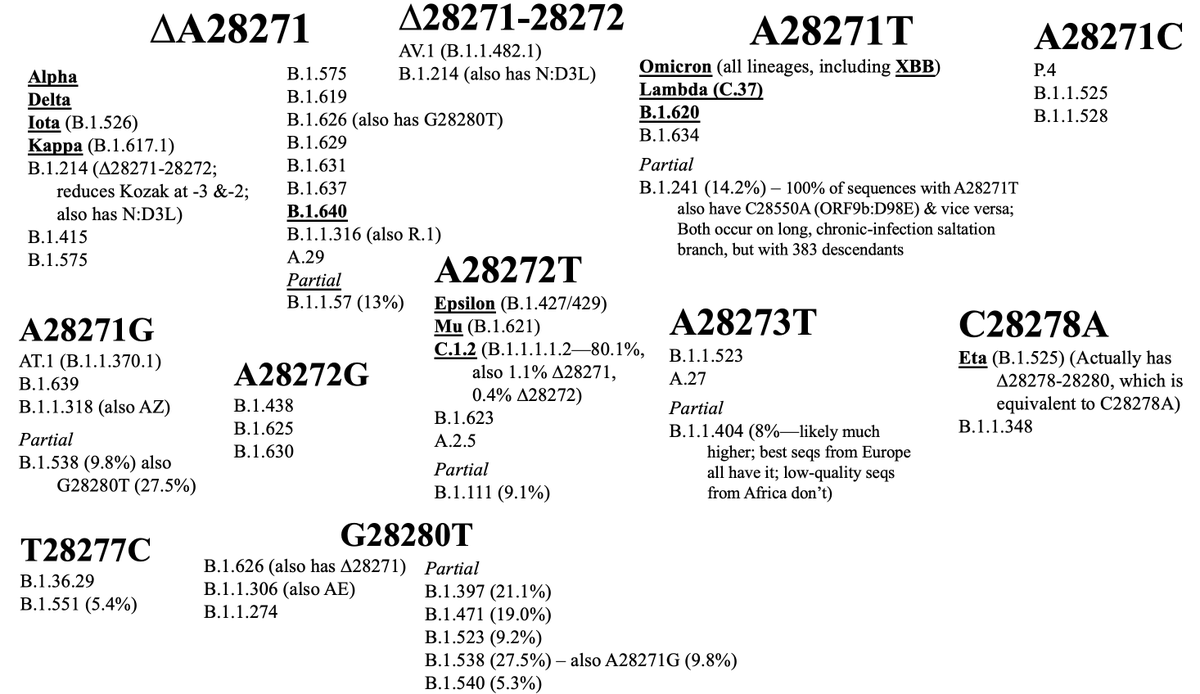

Another neglected ORF9b-related feature of chronic infections (& CI-derived variants) is the repeated destruction of the N Kozak sequence, which dramatically increases ORF9b expression. See 46-53 in thread below for a partial outline of this.

40/

40/

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1673493125929598978

I did not mention in that thread that these N-Kozak-killing, ORF9b-enhancing mutations can be found in *virtually every major variant* of the VOC era. There are only two major exceptions: Beta and Gamma.

41/64

41/64

But even Beta and Gamma managed to increase ORF9b protein expression about 3-4-fold compared to WT through unknown mechanisms.

(graph via @KroganLab @DoctorBou @lucygthorne @akreuschl)

42/64

(graph via @KroganLab @DoctorBou @lucygthorne @akreuschl)

42/64

And Beta may have simply arrived too early: 5 of 7 chronic Betas I’ve found acquired one of the three maximal N-Kozak killers (A28271T, A28271C, or ∆A28271).

43/64

43/64

There’s also a plausible explanation for Gamma’s lack of an N-Kozak killer. ORF9b seems to be the most vulnerable SARS-CoV-2 protein to K48 ubiquitination & degradation by the proteasome, as documented by two excellent papers in mBio & @JVirology.

44/64

44/64

Gamma is the only major variant to have the classic chronic mutation ORF1a:K1795Q—also found in virtually all related Bat-CoVs. This mutation dramatically increases the NSP3 PLpro domain’s ability to deubiquitinate K48-tagged proteins.

45/

45/

So it seems plausible that, like other sarbecoviruses, Gamma has no need to increase ORF9b because its PLpro efficiently prevents ORF9b degradation. Perhaps there’s even more active ORF9b protein in Gamma-infected cells than in any other variant.

46/64

46/64

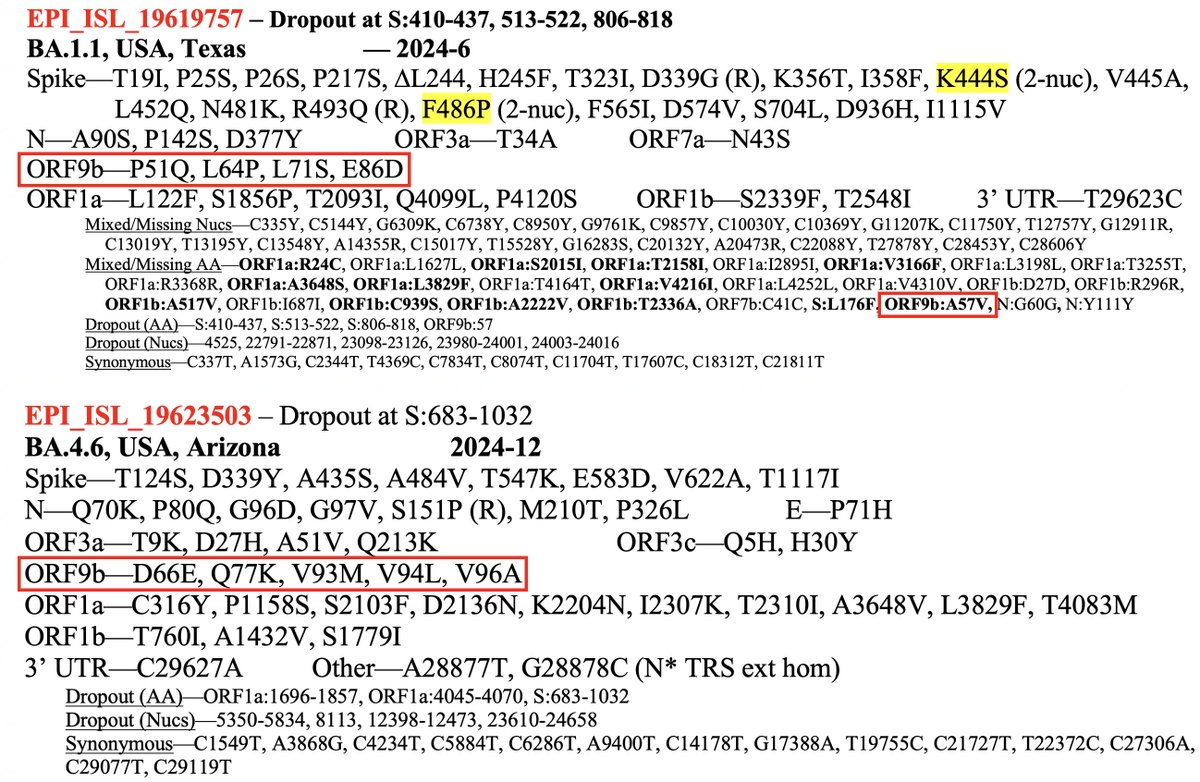

Three sequences uploaded in the past week (two collected in Dec 2024) exemplify the high ORF9b mutation rate in chronic infections—and two other striking ORF9b trends in chronics.

47/64

47/64

First a BA.1.1 from Texas with 4.5 ORF9b mutations & a BA.4.6 from Arizona with five.

BA.1.1 (collected June 2024): P51Q, L64P, L71S, E86D + A57V (mixed)

BA.4.6 (Dec 2024): D66E, Q77K, V93M, V94L, V96A

48/64

BA.1.1 (collected June 2024): P51Q, L64P, L71S, E86D + A57V (mixed)

BA.4.6 (Dec 2024): D66E, Q77K, V93M, V94L, V96A

48/64

And a BA.5.2 with a stunning eight private ORF9b mutations:

R13H, G16D (R), R47H, P51Q, L64P, A75V, E86D, V93L

The two major trends in ORF9b mutations in chronics can be seen here:

#1) C-terminal muts, often in clusters

#2) Reversions to Bat-CoV residues

49/64

R13H, G16D (R), R47H, P51Q, L64P, A75V, E86D, V93L

The two major trends in ORF9b mutations in chronics can be seen here:

#1) C-terminal muts, often in clusters

#2) Reversions to Bat-CoV residues

49/64

Here’s an alignment of the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral ORF9b aligned with closely related sarbecovirus ORF9b seqs. The second sequence is the consensus sarbeco ORF9b. The 6 reversions to Bat-CoV residues in these 3 chronics are labeled.

50/64

50/64

Many other 9b “reversions” are also common, both in chronics & in circulation—I5T, in particular was seen in chronic infections years before it became ~universal in XBB.1.9’s descendants. Others include R32H, D33G, G38D, N55S (XBB.1.16), & N62D.

51/64

51/64

What are the C-terminal ORF9b mutation clusters about? The ORF9b monomer CTD is disordered & projects outward. In the dimer, the CTD is also on the exposed outer edge of the protein, perhaps making it vulnerable to antibodies or T-cell attack.

52/64

52/64

Anyway, my mutation density measure masks huge variations in mutation density within proteins. For a subset of proteins, I separated out the various known domains. As expected, spike RBD is the runaway winner here. I need to add domains for E, M, ORF9b, ORF3a, & others.

53/64

53/64

NSP12 palm region spans 2 separate regions of the linear AA seq separated by a linker region. The linker has a much higher mutation rate, & this is generally true for NSP3 (& likely others) as well. But exact NSP3 linker residues aren’t well defined, so I didn’t include them.

54/

54/

I have one other nano-quibble that wouldn’t merit mentioning except that it leads to a more important point. They state that BA.2.86, before acquiring L455S & becoming JN.1, had limited spread. In fact, it spread quite widely & was among the fastest lineages globally.

55/64

55/64

This was despite BA.2.86 having weaker antibody-evasion than other circulating lineages at the time—and exhibiting weaker infectivity in vitro. So why did BA.2.86 spread at all?

56/64

56/64

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1698861010117972412

Partly, this may have been due to an increased ability to utilize cell-surface heparan sulfate as a co-receptor, as @yunlong_cao & @GuptaR_lab showed in a fascinating paper.

57/64

57/64

https://x.com/GuptaR_lab/status/1805215852288999654

There’s more to the story than just that, but I think

@StuartTurville may be the only person in the world (along with Stefan Pöhlmann) who can properly explain it, so I’ll leave the story to him.

58/64

@StuartTurville may be the only person in the world (along with Stefan Pöhlmann) who can properly explain it, so I’ll leave the story to him.

58/64

The excellent discussion section of Sigal & Neher’s paper is a treat. In describing the extreme rarity of chronic-infection variants, they make a point that should be obvious but which many fail to grasp: a single infection is all it takes.

59/64

59/64

Furthermore, the random nature and timing of these divergent variants means traditional seasonal vaccination schedules are inadequate, and future changes in disease severity & symptoms are entirely possible, something @georgimarinov has discussed.

60/64

60/64

Finally, the fundamental questions: Why do we see this in SARS-CoV-2 & not influenza or other viruses? A mostly uniform immune history & antigenic imprinting (OAS) may be part of it. Could the rampant recombination typical of CoVs factor in as well?

61/64

61/64

And what to make of the many, many studies showing signs of persistent viral RNA or proteins—most recently in the “skull-meninges-brain axis”—even in the immunocompetent? I feel more baffled than ever on this front, & have nothing useful to add.

62/64

cell.com/cell-host-micr…

62/64

cell.com/cell-host-micr…

I’ve always been skeptical that viral RNA or proteins could persist for many months or years with no viral replication occurring, except maybe in germinal centers. Are the skull meninges immune privileged enough to be an exception? Or is my skepticism is wholly unjustified?

63/64

63/64

I haven’t read much comment or discussion among experts on that study, which seems extremely well done & potentially really important. Would love to hear more expert thoughts on this.

64/64

64/64

https://x.com/erturklab/status/1862524693640564871

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh