One of Britain’s Greatest Naval Disasters: The Cadiz Expedition of 1625:

In 1625, Britain suffered one of its greatest naval blunders against Spain when a massive force of 100 ships and 15.000 men attempted to raid Cádiz and seize the Spanish treasure fleet. The campaign required a huge financial investment but ultimately yielded almost nothing in return. The failed expedition caused significant political backlash for King Charles I and his close advisor, the Duke of Buckingham. This episode arguably marked the beginning of the decline for the ill-fated Stuart king, whose popularity plummeted after the disastrous venture to Cádiz.

In 1625, Britain suffered one of its greatest naval blunders against Spain when a massive force of 100 ships and 15.000 men attempted to raid Cádiz and seize the Spanish treasure fleet. The campaign required a huge financial investment but ultimately yielded almost nothing in return. The failed expedition caused significant political backlash for King Charles I and his close advisor, the Duke of Buckingham. This episode arguably marked the beginning of the decline for the ill-fated Stuart king, whose popularity plummeted after the disastrous venture to Cádiz.

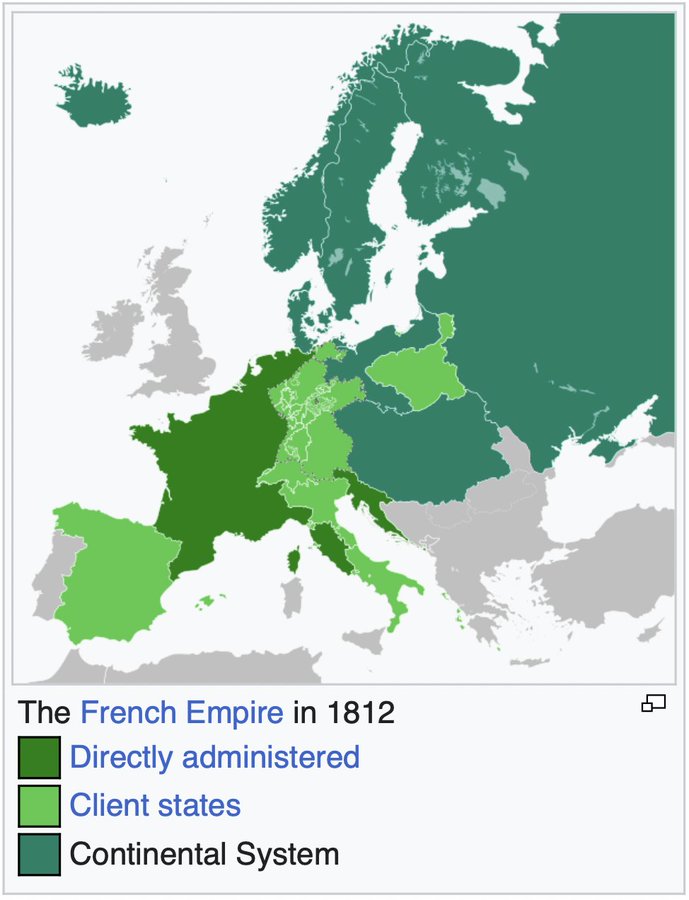

It all began before Charles ascended the throne, while his father, James I—the first king of the House of Stuart—was still in power. After a history marked by strained relations, bloodshed, and political intrigue, England sought to improve its relationship with the dominant superpower of the time: Spain. Religion played a significant role in the ongoing tension between the two kingdoms. Since England's break with Rome, the staunchly Catholic Spaniards had viewed the island nation with disdain.

Although King James I was baptized Catholic, he was raised Protestant and understood that the monarchy's strength relied on a strong Anglican Church, and consequently the persecution of Catholics continued. Nevertheless, James I hoped to secure an alliance with Spain by arranging a marriage between his son Charles and the Infanta Maria Anna. The whole marriage deal collapsed, however, and the disillusioned Prince Charles, along with the Duke of Buckingham, now pursued a different course in dealing with Spain: war!

Charles and Buckingham convinced King James to summon a new Parliament in 1624, which strongly advocated for war with Spain. However, there was a lot of mutual distrust between James and Parliament: James feared they wouldn’t fund the war, while Parliament feared he wouldn’t go through with the plan after the funds had been given. After James died, Charles took over, assuming that Parliament would provide funds if he pursued their war policy, but this assumption proved overly optimistic.

Eventually Parliament was convinced by the new king and war was declared on Spain. Buckingham, as Lord High Admiral, began preparing the expedition with two main objectives: to capture Spanish treasure ships from the Americas and to attack Spanish towns to disrupt their economy.

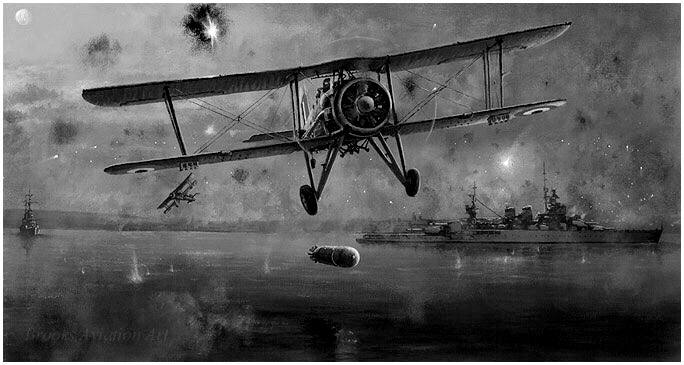

Success was crucial, as this would encourage Parliament to fund other future campaigns of Charles and Buckingham. By October 1625, around 100 ships and 15,000 soldiers and sailors were assembled for the Cádiz expedition, supported by 15 Dutch warships.

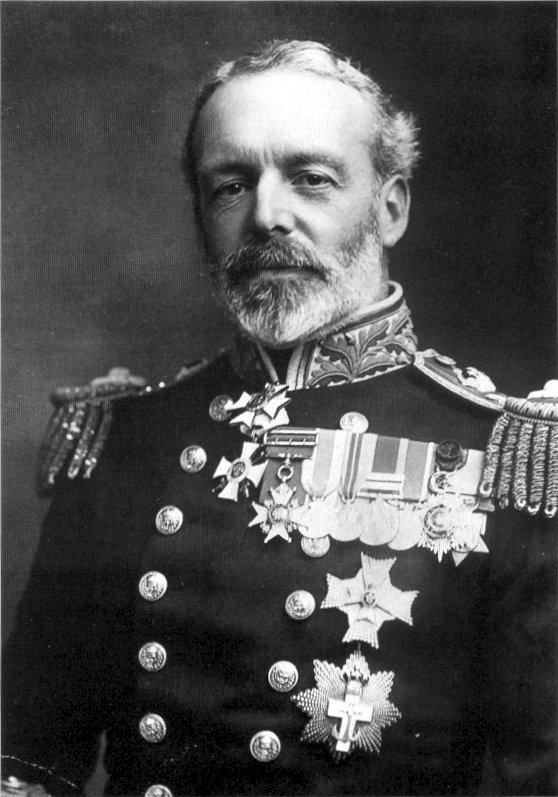

Some of the Dutch ships remained in the Channel to protect the waters from enemy attack, while others joined the English raid. Sir Edward Cecil, an experienced soldier but inexperienced at sea, was appointed commander—a choice that would later be seen as poor judgment.

The fleet set sail from Plymouth on October 6, 1625, but encountered severe storms. Although no ships from the Allied fleet sank, some were forced to turn back. The harsh weather delayed the mission and prevented them from intercepting the Spanish treasure fleet in time.

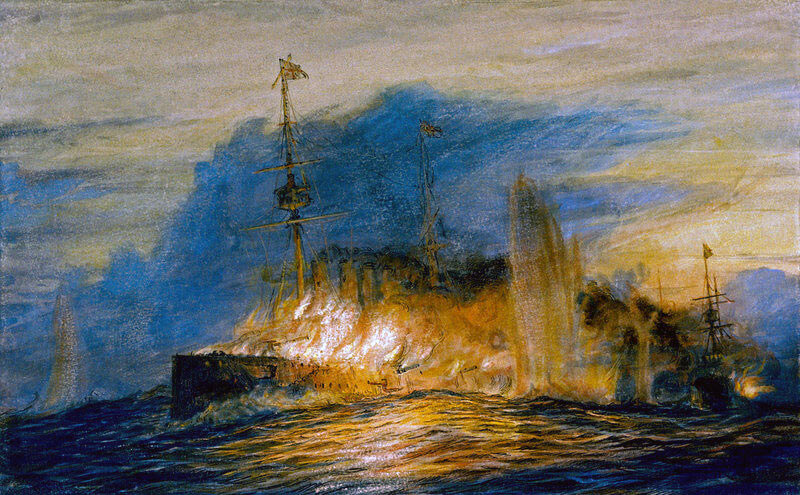

When they finally reached Cádiz, Cecil managed to capture the fort guarding the harbor, but the city itself was more heavily fortified than he had anticipated. Furthermore, miscommunication and hesitation among the English allowed the Spanish ships in Cádiz to escape. It was at this point that the English began to realize how poorly they had prepared for the expedition, lacking sufficient food and water for the troops. Nevertheless, Cecil and his forces pressed on.

The English commander then ordered the capture of Puntal tower, an unnecessary move as the fortification provided no strategic advantage for further efforts against Cádiz. Afterward, the men began looting the surrounding houses and discovered a warehouse full of wine. Most of Cecil’s troops became so drunk that he could no longer control them.

To make matters worse, Spanish troops arrived and attacked the intoxicated English soldiers, who stood no chance against their sober opponents. It is said that the English were so drunk they didn't bother using their guns, defending themselves with swords instead. Around 1,000 Englishmen were slaughtered, and the remaining troops fled back to the ships.

Facing significant losses, low morale, and no real gains, Cecil made the drastic decision to abandon the siege of Cádiz. He pinned his last hopes on capturing some Spanish treasure ships, but his attempt to intercept the returning galleons from the New World also failed, as the Spanish had been warned of the English presence and took an alternate route.

With disease spreading and supplies running low, Cecil called off the mission and returned to England in December 1625. The expedition was a costly failure, yielding little and with the total costs estimated at £250,000.

However, the House of Commons was far less forgiving. In the Parliament of 1626, they initiated impeachment proceedings against Buckingham. To avoid a successful impeachment, Charles dissolved Parliament. The king's popularity waned and would continue to decline during a reign marked by poor decisions, ultimately leading to his downfall and execution.

Olivier Goossens

Olivier Goossens

If you have enjoyed this short article, please consider supporting the channel by subscribing to my Patreon or by leaving a donation on “Buy Me a Coffee”.

Patreon: patreon.com/c/OlivierGooss…

Buy Me a Coffee: buymeacoffee.com/heartofoak

Patreon: patreon.com/c/OlivierGooss…

Buy Me a Coffee: buymeacoffee.com/heartofoak

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh