The Heart of British Naval History / Online Blog / By Olivier Goossens / Enquiries: heartofoak1805@gmail.com

3 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

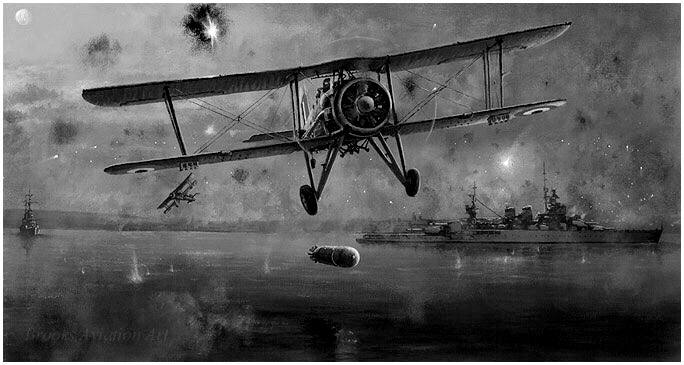

On the night of November 11-12, 1940, 21 British biplanes, Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, took off from HMS Illustrious with one daring target in mind: the Italian fleet in Taranto. These “Stringbags,” often mocked for their outdated design, were about to make history

On the night of November 11-12, 1940, 21 British biplanes, Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, took off from HMS Illustrious with one daring target in mind: the Italian fleet in Taranto. These “Stringbags,” often mocked for their outdated design, were about to make history

(2/8) ⛴️ Prior to Coronel, the Royal Navy had been scouring the Pacific for months, seeking Spee’s German East Asia Squadron with the help of the Japanese. Britain aimed to neutralize Spee’s commerce raiders, which had relocated from the Far East to South America after Japan joined the war on Britain’s side.

(2/8) ⛴️ Prior to Coronel, the Royal Navy had been scouring the Pacific for months, seeking Spee’s German East Asia Squadron with the help of the Japanese. Britain aimed to neutralize Spee’s commerce raiders, which had relocated from the Far East to South America after Japan joined the war on Britain’s side.

The year is 1807. Nelson has been dead for two years, but his legacy endures. The French lack the resolve and resources to challenge the British in another major open-sea engagement. The threat of invasion had faded.

The year is 1807. Nelson has been dead for two years, but his legacy endures. The French lack the resolve and resources to challenge the British in another major open-sea engagement. The threat of invasion had faded.

When the keel of the Victory was laid down, no one could have predicted the name she would eventually bear—a name once marred by tragedy. The previous Victory, launched in 1737, was also a first-rate ship of the line. Unlike her successor, however, this Victory had a brief and ill-fated career. On the night of October 4–5, 1744, the massive battleship foundered during a violent storm in the English Channel.

When the keel of the Victory was laid down, no one could have predicted the name she would eventually bear—a name once marred by tragedy. The previous Victory, launched in 1737, was also a first-rate ship of the line. Unlike her successor, however, this Victory had a brief and ill-fated career. On the night of October 4–5, 1744, the massive battleship foundered during a violent storm in the English Channel.

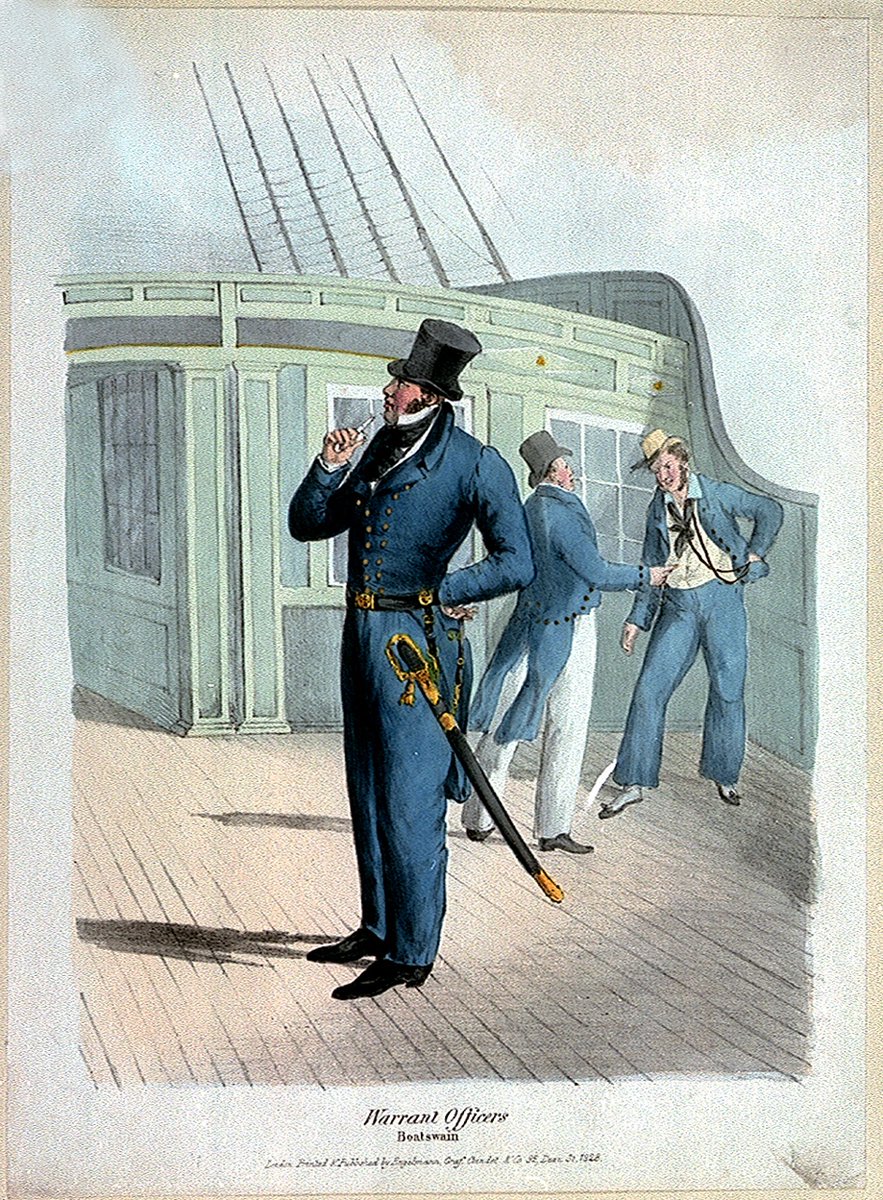

(2/8) Just like other warrant officers, the boatswain was appointed by a paper warrant from the Navy Board, instead of a commission on parchment issued by the Board of Admiralty and reserved for higher-ranking officers. In the time of Nelson, the boatswain was in charge of the boats, sails, colours, anchors, cables, and cordage. Having risen from the ranks of seamen, he was usually a man of respectable age, sourcing his vast knowledge on these matters from years of experience. Before receiving the warrant of boatswain, however, a one-year trial with the captain as a petty officer was obligatory. Another requirement was that he be literate, as per Admiralty Regulations, a rule obligatory for all warrant officers.

(2/8) Just like other warrant officers, the boatswain was appointed by a paper warrant from the Navy Board, instead of a commission on parchment issued by the Board of Admiralty and reserved for higher-ranking officers. In the time of Nelson, the boatswain was in charge of the boats, sails, colours, anchors, cables, and cordage. Having risen from the ranks of seamen, he was usually a man of respectable age, sourcing his vast knowledge on these matters from years of experience. Before receiving the warrant of boatswain, however, a one-year trial with the captain as a petty officer was obligatory. Another requirement was that he be literate, as per Admiralty Regulations, a rule obligatory for all warrant officers.

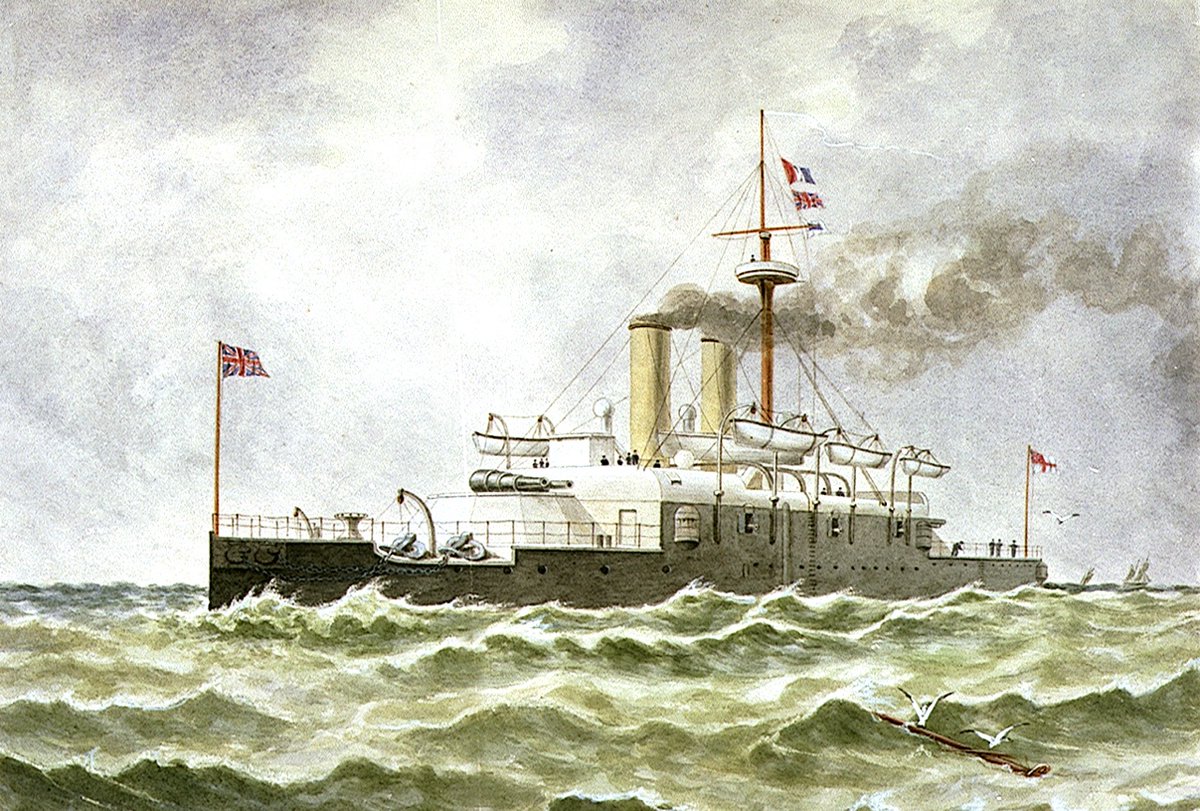

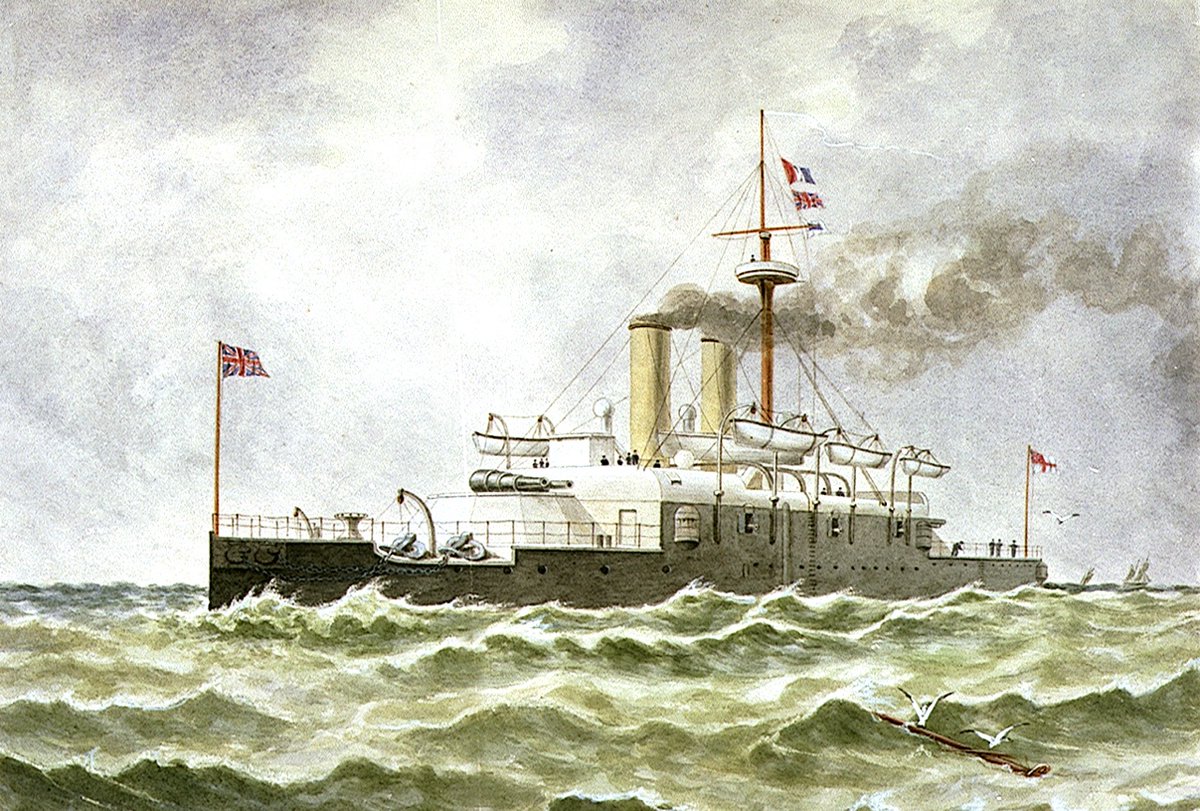

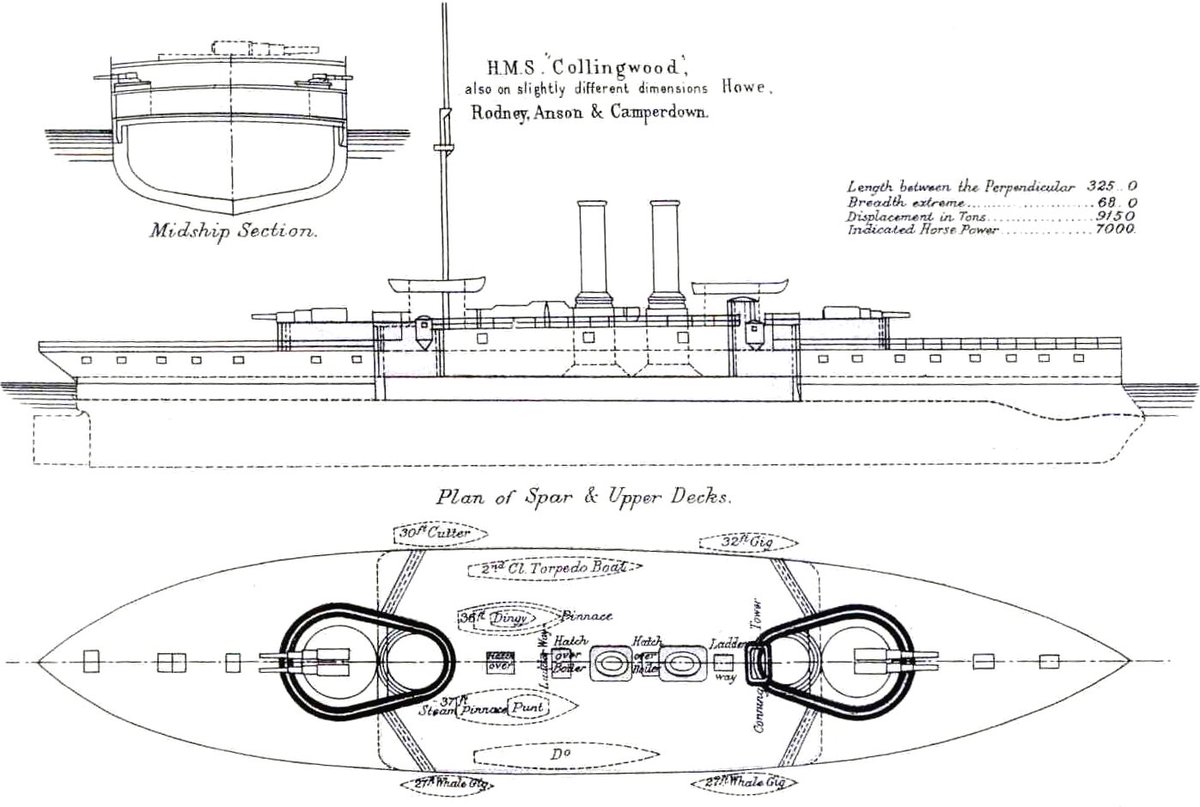

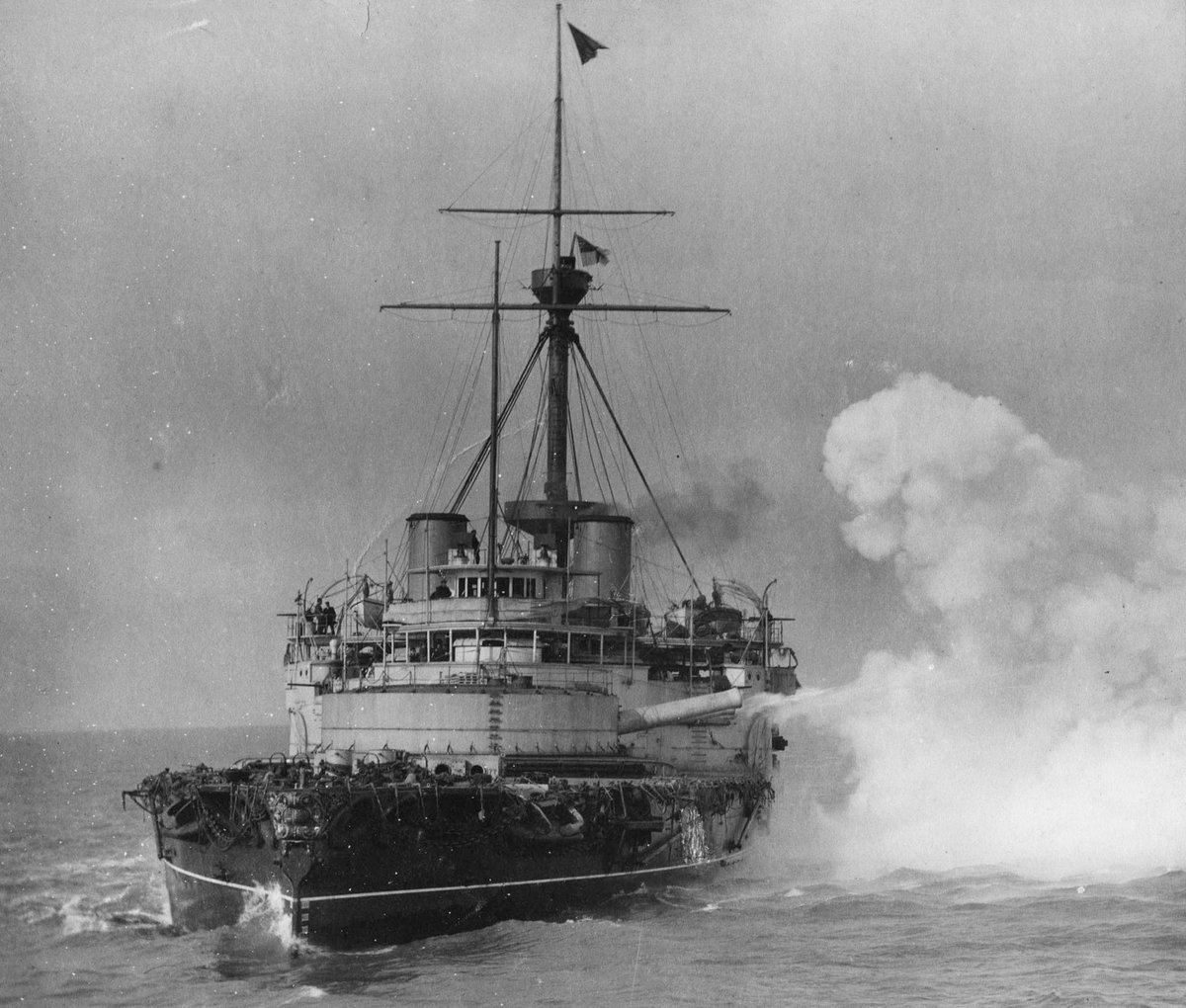

At her conception, Collingwood was not intended as the prototype of a new class but rather as a one-off response by Sir Nathaniel Barnaby, Director of Naval Construction, to the French Amiral Baudin and Terrible-class ironclads. His final design echoed Devastation with fore-and-aft main armament in barbettes, set higher above the waterline, but the Admiralty altered it by lengthening the hull, adding horsepower for a 15-knot speed, and substituting smaller guns. These changes, along with lines taken from Colossus, increased displacement by 2,500 tons.

At her conception, Collingwood was not intended as the prototype of a new class but rather as a one-off response by Sir Nathaniel Barnaby, Director of Naval Construction, to the French Amiral Baudin and Terrible-class ironclads. His final design echoed Devastation with fore-and-aft main armament in barbettes, set higher above the waterline, but the Admiralty altered it by lengthening the hull, adding horsepower for a 15-knot speed, and substituting smaller guns. These changes, along with lines taken from Colossus, increased displacement by 2,500 tons.

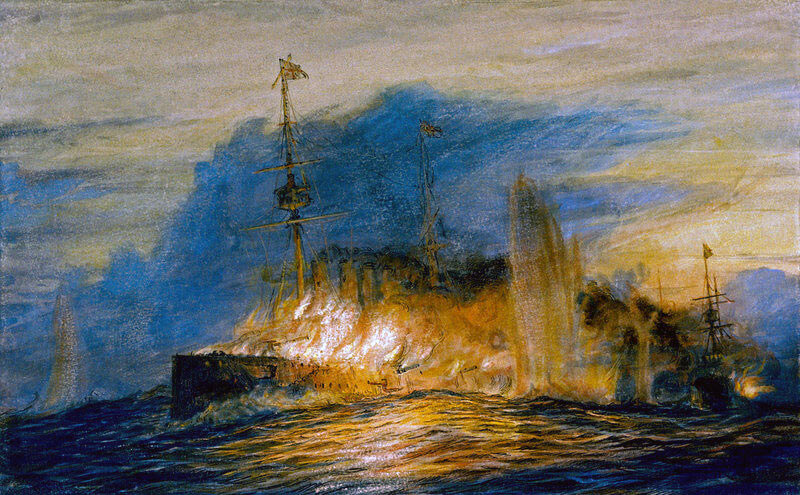

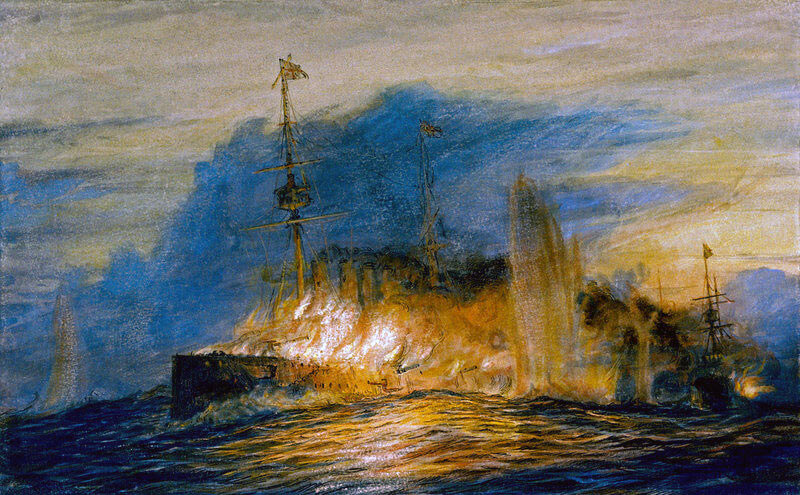

The Battle of Navarino, fought on 20 October 1827, proved to be the decisive turning point of the Greek War of Independence. For much of the conflict, the Ottoman Empire, supported by its Egyptian vassal state, had managed to suppress the rebellion and seemed on the verge of crushing it altogether. At this moment, however, the three European powers—Britain, France, and Russia—intervened, dispatching fleets to the eastern Mediterranean. Their intervention culminated in the destruction of the Ottoman and Egyptian naval forces in what would become the last great fleet action fought entirely by sailing ships.

The Battle of Navarino, fought on 20 October 1827, proved to be the decisive turning point of the Greek War of Independence. For much of the conflict, the Ottoman Empire, supported by its Egyptian vassal state, had managed to suppress the rebellion and seemed on the verge of crushing it altogether. At this moment, however, the three European powers—Britain, France, and Russia—intervened, dispatching fleets to the eastern Mediterranean. Their intervention culminated in the destruction of the Ottoman and Egyptian naval forces in what would become the last great fleet action fought entirely by sailing ships.

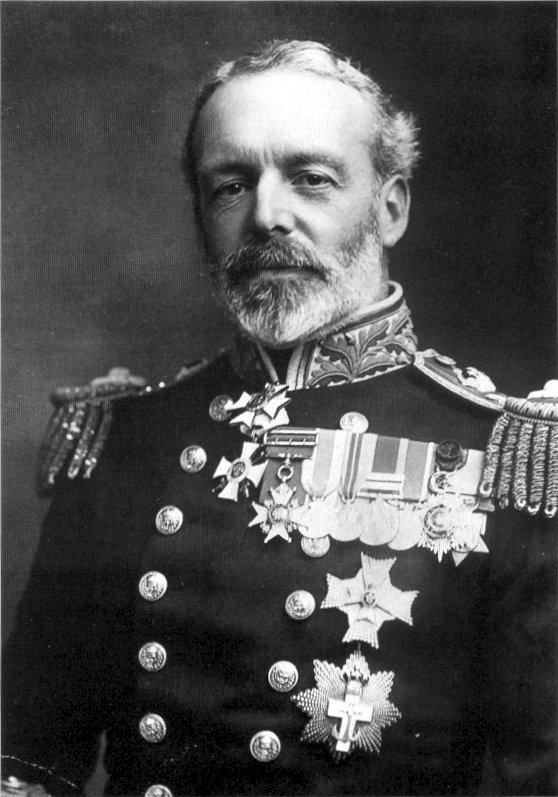

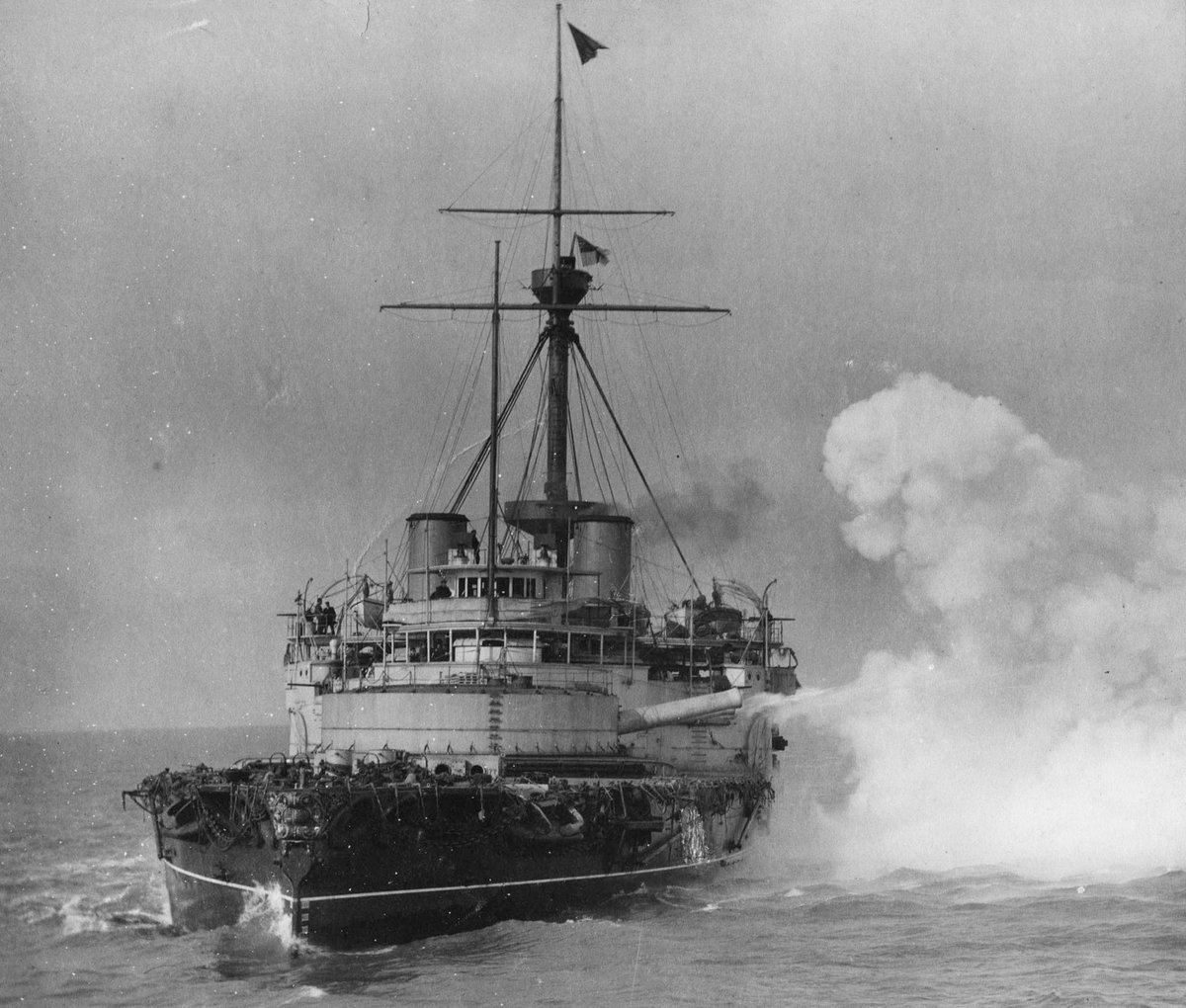

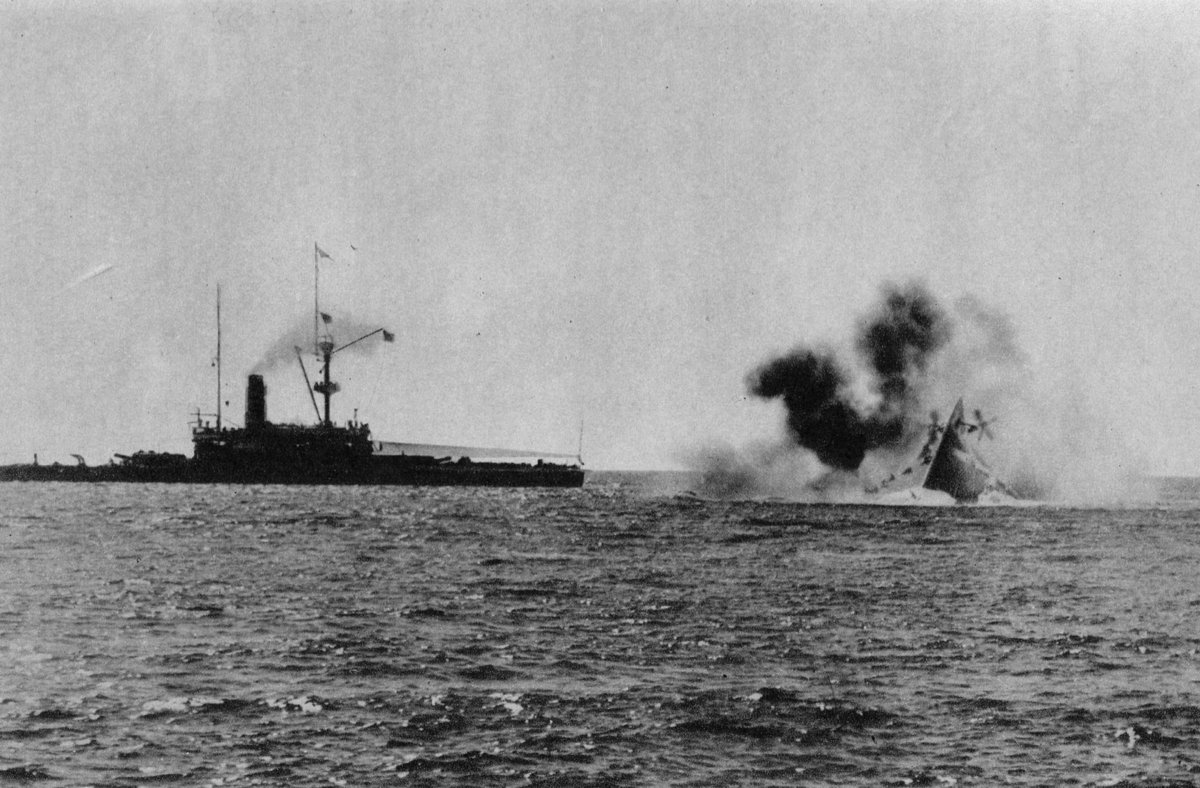

HMS Victoria was the first of two battleships in her class serving with the Royal Navy. On 22 June 1893, she collided with HMS Camperdown during manoeuvres off Tripoli, Lebanon, and sank rapidly, claiming the lives of 358 crew members, among them the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon. Among the survivors was the ship’s executive officer, John Jellicoe, who would later command the British Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland.

HMS Victoria was the first of two battleships in her class serving with the Royal Navy. On 22 June 1893, she collided with HMS Camperdown during manoeuvres off Tripoli, Lebanon, and sank rapidly, claiming the lives of 358 crew members, among them the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon. Among the survivors was the ship’s executive officer, John Jellicoe, who would later command the British Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland.

![The capture of the slaver ‘Bolodora’ [Voladora], 6 June 1829. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Caird Fund.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GwUZ7D0XkAAgE7j.jpg) On 25 March 1807, the United Kingdom abolished the slave trade. More than two decades later, slavery was abolished altogether in the British Empire through the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. More than 800,000 individuals were freed from slavery with immediate effect in Canada, South Africa, and the Caribbean. The United Kingdom used its most valuable instrument, the Royal Navy, to enforce the ban on the slave trade. Between 1807 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron intercepted around 1,600 slave ships and liberated over 150,000 Africans from the grim fate of slavery.

On 25 March 1807, the United Kingdom abolished the slave trade. More than two decades later, slavery was abolished altogether in the British Empire through the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. More than 800,000 individuals were freed from slavery with immediate effect in Canada, South Africa, and the Caribbean. The United Kingdom used its most valuable instrument, the Royal Navy, to enforce the ban on the slave trade. Between 1807 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron intercepted around 1,600 slave ships and liberated over 150,000 Africans from the grim fate of slavery.

Historical Background

Historical Background

In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, the Americans assembled a naval armada known as the Penobscot Expedition. This fleet comprised 40 vessels—18 armed warships or privateers and 22 schooners or sloops serving as troop transports. It was the largest American fleet assembled during the Revolutionary War, setting sail on July 19 from Boston and heading toward Penobscot Bay in Maine.

In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, the Americans assembled a naval armada known as the Penobscot Expedition. This fleet comprised 40 vessels—18 armed warships or privateers and 22 schooners or sloops serving as troop transports. It was the largest American fleet assembled during the Revolutionary War, setting sail on July 19 from Boston and heading toward Penobscot Bay in Maine.

The Leander-class was a group of eight light cruisers built for the Royal Navy during the 1930s, which saw extensive service during the Second World War. They were constructed in two groups: five of the Leander group, which were destined for the Royal Navy, and a further three of the Amphion group which were later transferred to the Royal Australian Navy. Two units, the Achilles and Leander, would later join the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, making New Zealand a 2-cruiser station, a number the island would maintain until the 60s. The British and New Zealand vessels were named after figures from classical mythology, while the Australian ships were named after Australian cities.

The Leander-class was a group of eight light cruisers built for the Royal Navy during the 1930s, which saw extensive service during the Second World War. They were constructed in two groups: five of the Leander group, which were destined for the Royal Navy, and a further three of the Amphion group which were later transferred to the Royal Australian Navy. Two units, the Achilles and Leander, would later join the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, making New Zealand a 2-cruiser station, a number the island would maintain until the 60s. The British and New Zealand vessels were named after figures from classical mythology, while the Australian ships were named after Australian cities.

Between April 9 and 12, 1782, over the course of four days, the Royal Navy achieved its greatest victory against the French during the American War of Independence, when Admiral Sir George Rodney defeated a French fleet of over 30 French ships of the line under Comte de Grasse. He successfully thwarted the planned invasion of Jamaica and restored British naval dominance in the West Indies. The French momentum was broken, and the British could now open peace negotiations from a position of power. This final engagement of the American Revolution is also considered by some to be the first instance of the use of the battle tactic of ‘breaking the line.’

Between April 9 and 12, 1782, over the course of four days, the Royal Navy achieved its greatest victory against the French during the American War of Independence, when Admiral Sir George Rodney defeated a French fleet of over 30 French ships of the line under Comte de Grasse. He successfully thwarted the planned invasion of Jamaica and restored British naval dominance in the West Indies. The French momentum was broken, and the British could now open peace negotiations from a position of power. This final engagement of the American Revolution is also considered by some to be the first instance of the use of the battle tactic of ‘breaking the line.’

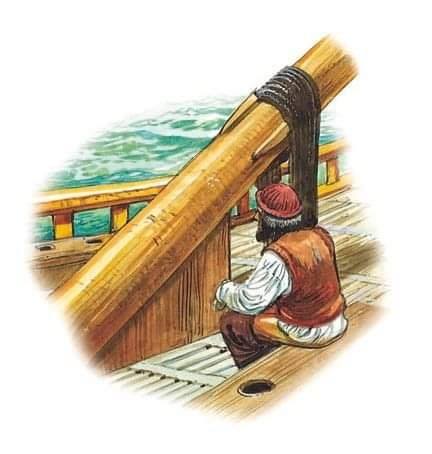

Some 800 men lived and worked aboard a first-rate ship of the line, such as HMS Victory. These ships needed to be kept in good condition at all times. Every sailor received a fixed amount of food rations daily. However, this is only part of the story. As we all know, after eating comes the need to visit the toilet. How did this happen aboard a ship of the line in the 18th century? Where did the sailors go to do their business?

Some 800 men lived and worked aboard a first-rate ship of the line, such as HMS Victory. These ships needed to be kept in good condition at all times. Every sailor received a fixed amount of food rations daily. However, this is only part of the story. As we all know, after eating comes the need to visit the toilet. How did this happen aboard a ship of the line in the 18th century? Where did the sailors go to do their business?

(1/8) The Hermione, handed to the Spanish by its mutinous British crew, was anchored in the heavily guarded Puerto Cabello. Led by Edward Hamilton, HMS Surprise was tasked with retaking the ship through a high-stakes "cutting out" operation—a stealthy, surprise boarding attack.

(1/8) The Hermione, handed to the Spanish by its mutinous British crew, was anchored in the heavily guarded Puerto Cabello. Led by Edward Hamilton, HMS Surprise was tasked with retaking the ship through a high-stakes "cutting out" operation—a stealthy, surprise boarding attack.

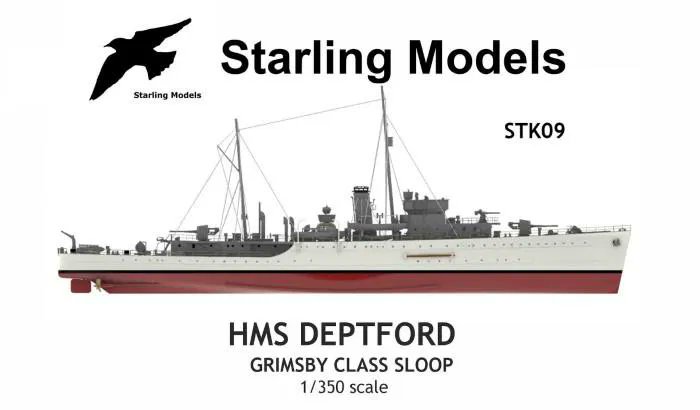

(1/7) HMS Grimsby (U16) was the lead ship of the Grimsby-class sloops, a class of 13 vessels built between 1933 and 1940. The small, 990-ton ship measured 266 ft 3 in (81.15 m) in length, 36 ft (11.0 m) in beam, and had a draught of 9 ft 6 in (2.90 m) at full load.

(1/7) HMS Grimsby (U16) was the lead ship of the Grimsby-class sloops, a class of 13 vessels built between 1933 and 1940. The small, 990-ton ship measured 266 ft 3 in (81.15 m) in length, 36 ft (11.0 m) in beam, and had a draught of 9 ft 6 in (2.90 m) at full load.

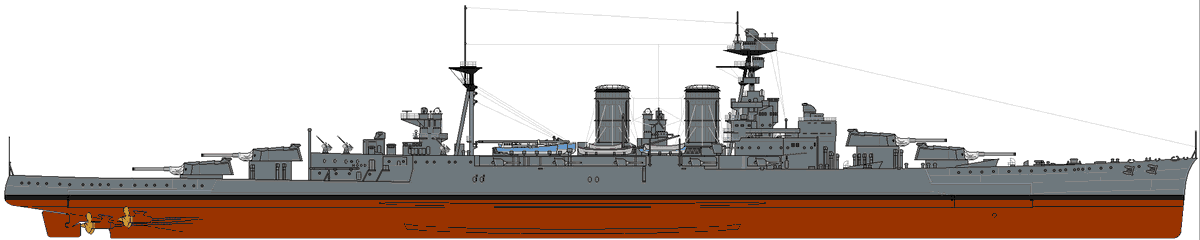

(1/9) HMS Hood was an Admiral-class battlecruiser, a class originally planned to consist of four ships. However, the Battle of Jutland in 1916 cast doubt on the viability of the battlecruiser concept, and the imminent defeat of Germany rendered the construction of additional battlecruisers unnecessary. As a result, only one ship was completed: HMS Hood.

(1/9) HMS Hood was an Admiral-class battlecruiser, a class originally planned to consist of four ships. However, the Battle of Jutland in 1916 cast doubt on the viability of the battlecruiser concept, and the imminent defeat of Germany rendered the construction of additional battlecruisers unnecessary. As a result, only one ship was completed: HMS Hood.

(1/7) HMS Fiji displaced 8,530 tons standard and over 10,700 tons at deep load. She was 555 feet (169.3 meters) long, with a beam of 62 feet (18.9 meters) and a draught of nearly 20 feet (6 meters). Powered by four Parsons geared steam turbines and four Admiralty boilers, she could reach speeds up to 32.25 knots. Fiji had a range of 6,520 nautical miles at 13 knots and carried a crew of 733 in peacetime, increasing to 900 during wartime.

(1/7) HMS Fiji displaced 8,530 tons standard and over 10,700 tons at deep load. She was 555 feet (169.3 meters) long, with a beam of 62 feet (18.9 meters) and a draught of nearly 20 feet (6 meters). Powered by four Parsons geared steam turbines and four Admiralty boilers, she could reach speeds up to 32.25 knots. Fiji had a range of 6,520 nautical miles at 13 knots and carried a crew of 733 in peacetime, increasing to 900 during wartime.

(1/8) HMS Belleisle was originally a French third-rate ship of the line (74 guns) of the Téméraire class. The Téméraire-class ships comprised 120 74-gun vessels ordered between 1782 and 1813 for the French Navy and its allied or occupied territories. Although a few were later cancelled, the class remains the most numerous series of capital ships ever built to a single design. The lines of the ship were originally drawn by Jacques-Noël Sané in 1782.

(1/8) HMS Belleisle was originally a French third-rate ship of the line (74 guns) of the Téméraire class. The Téméraire-class ships comprised 120 74-gun vessels ordered between 1782 and 1813 for the French Navy and its allied or occupied territories. Although a few were later cancelled, the class remains the most numerous series of capital ships ever built to a single design. The lines of the ship were originally drawn by Jacques-Noël Sané in 1782.

(1/8) HMS Wager was built around 1734 as an East Indiaman for the East India Company. She was armed with 30 guns and designed to carry large amounts of cargo. She was crewed by 98 men.

(1/8) HMS Wager was built around 1734 as an East Indiaman for the East India Company. She was armed with 30 guns and designed to carry large amounts of cargo. She was crewed by 98 men.