When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, it set off one of the biggest geopolitical shifts in recent history. The world—led by the U.S. and the EU—quickly realized that directly confronting a nuclear-armed superpower could have devastating consequences. Instead, the response came in the form of economic warfare, with sanctions becoming the main tool 🧵👇

Sanctions are essentially penalties imposed by countries or groups to limit a target nation’s ability to function economically or politically. The idea is straightforward: if open combat isn’t an option, especially with a nuclear power like Russia, you target the resources that fund its actions—its economy.

In Russia’s case, the West targeted its oil and gas sector, a critical pillar of its economy, accounting for roughly 15-20% of its GDP and a major source of funding for its war effort.

Image: Statista

Image: Statista

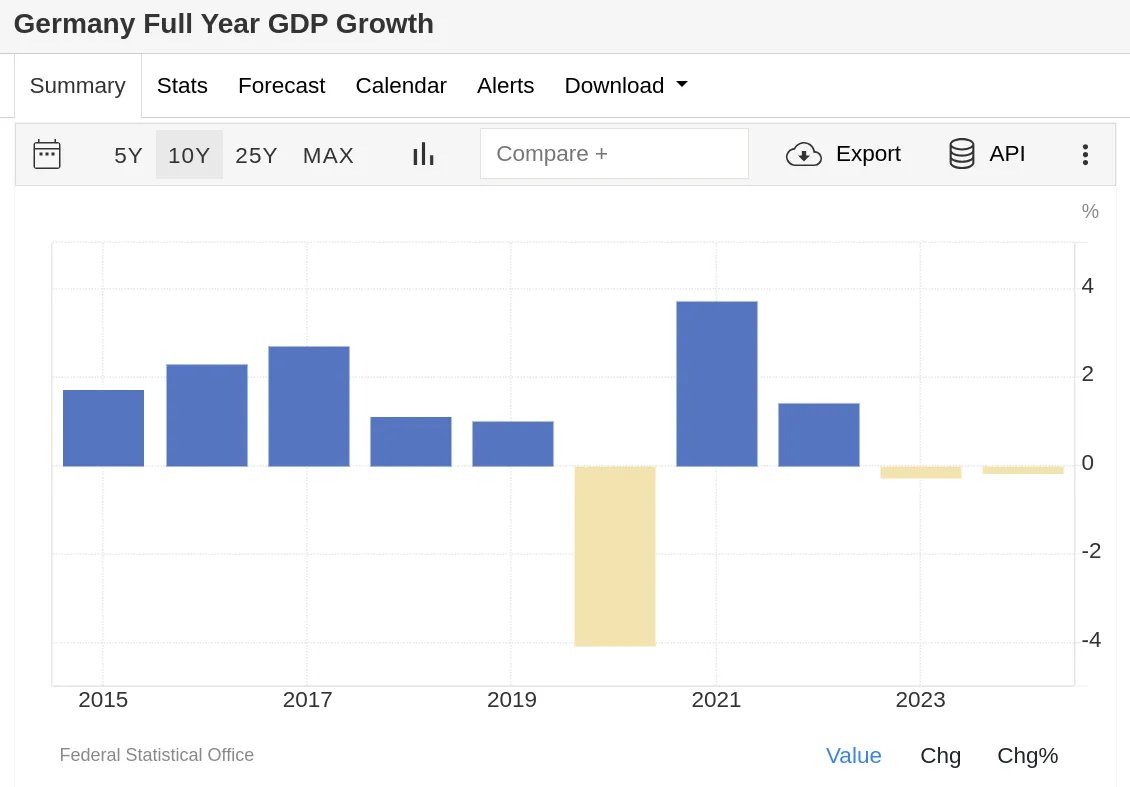

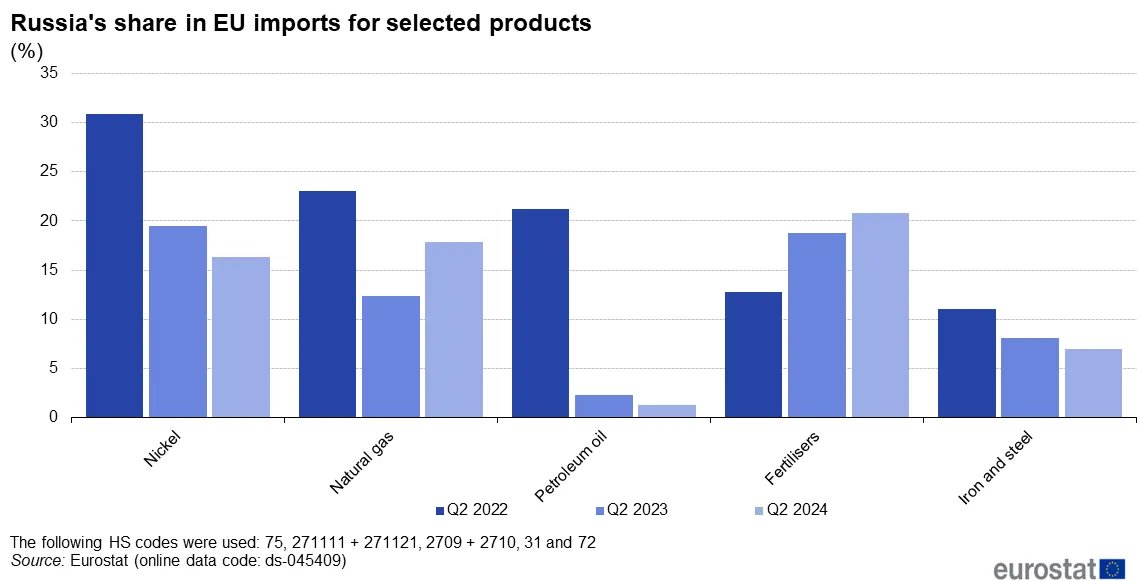

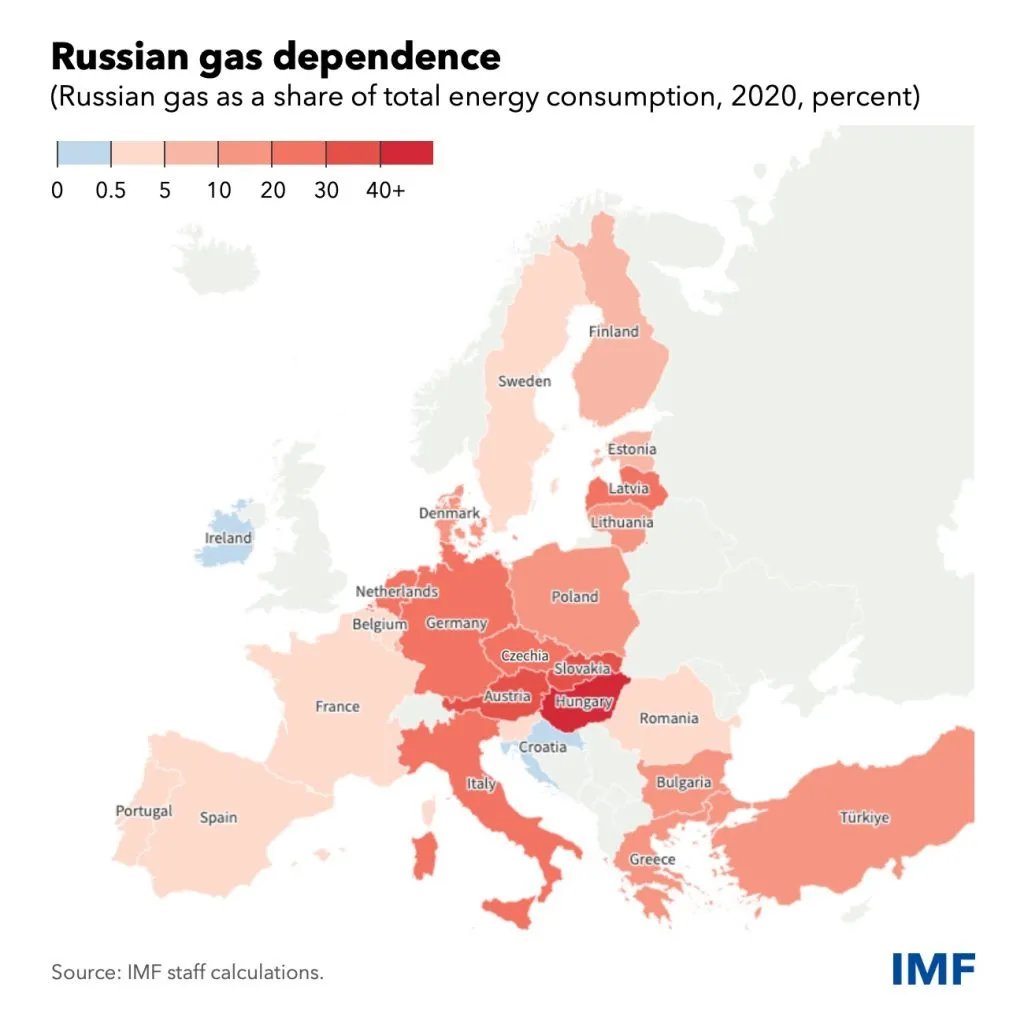

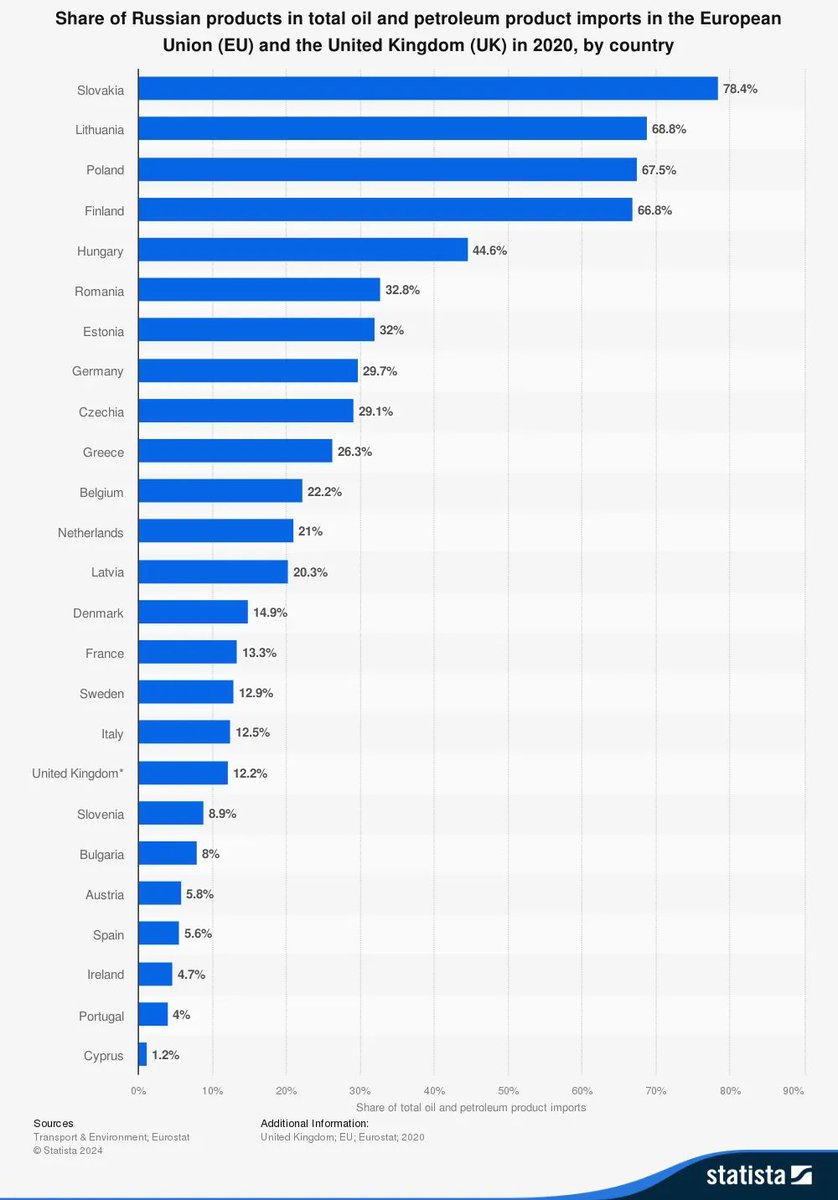

The first wave of sanctions imposed in 2022 was sweeping. Europe, once Russia’s largest energy customer, decided to drastically cut its dependence on Russian oil and gas.

Image: Eurostat

Image: Eurostat

At the start of the war, Europe accounted for over 50% of Russia’s energy exports. By the end of 2022, European purchases of Russian oil had plummeted.

Image: IMF & Statista

Image: IMF & Statista

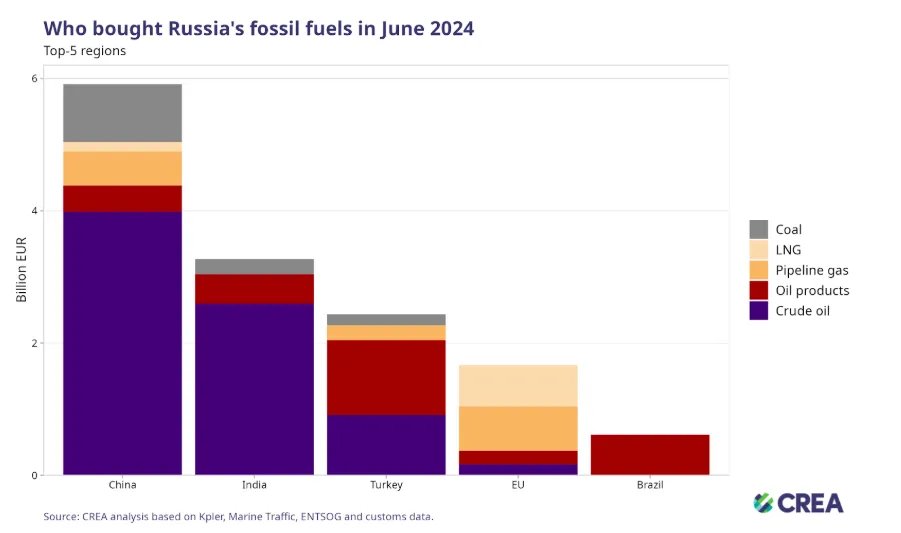

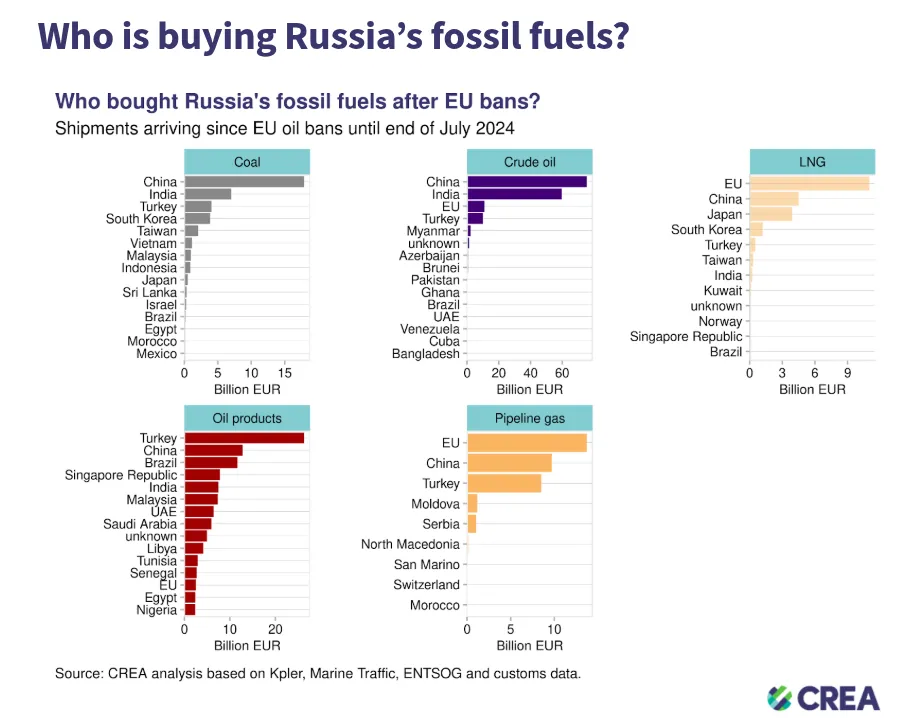

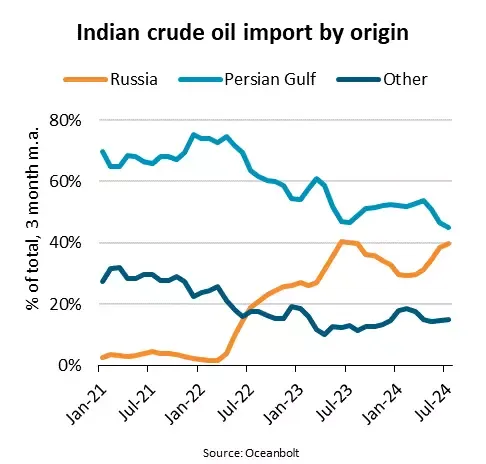

This left Moscow scrambling to find new buyers, and it didn’t take long for India and China to step in. Russia, desperate to keep its oil flowing, offered steep discounts—a lifeline for both nations, which were grappling with surging global oil prices.

The G7 also implemented a price cap of $60 per barrel on Russian crude. The enforcement mechanism was innovative: any tanker carrying Russian crude priced above this limit couldn’t be insured or financed by Western companies. Since Western firms dominate 90% of the marine insurance market, shipping Russian oil above the cap became riskier and more expensive.

To bypass these restrictions, Russia turned to a shadow fleet of older, poorly regulated tankers, some over 20 years old and often uninsured. This fleet became a key player in transporting discounted Russian oil to India and China, enabling Moscow to maintain its export volumes despite Western sanctions. However, the discounts came at a cost: Russia’s revenues from oil exports shrank as it sold crude at $20-30 below Brent crude prices.

Before 2022, Russian crude made up virtually none of India’s imports. By 2024, it accounted for 40-45%, helping India manage its $180-200 billion annual energy bill. Meanwhile, China, the world’s largest energy consumer, was purchasing nearly 47% of Russia’s total crude exports. The steep discounts made Russian oil not just attractive but essential for both nations.

Image: Energy and Clean Air / ITLN

Image: Energy and Clean Air / ITLN

Fast forward to 2025, and the U.S. has now imposed its toughest sanctions yet. These measures target two major Russian oil companies and 183 vessels out of more than 600 from Russia’s shadow fleet, tightening the loopholes that allowed Russian oil to flow freely to India and China. With fewer tankers available and higher risks involved in shipping, transporting Russian oil has become significantly more challenging.

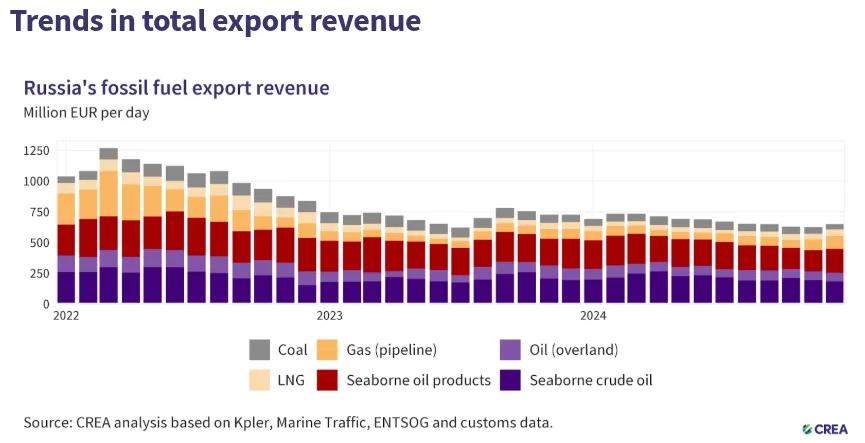

The U.S. aims to erode Russia’s oil revenues further, which have already been under pressure. Fossil fuel export earnings dropped by 5% year-on-year in 2024.

Image: Energy and Clean Air

Image: Energy and Clean Air

While crude oil revenues rose by 6% due to higher global prices, export volumes dropped by 2%. The new sanctions are expected to cut Russia’s oil revenues by another 20-25%, adding to its economic troubles.

For India and China, these sanctions are already creating challenges. Indian refiners, who had been relying heavily on discounted Russian crude, are now being forced to turn to Middle Eastern suppliers. Yogesh Patil, an energy expert, explained in an interview with the Economic Times that Indian oil companies will face difficulties since they can’t pass on the higher crude costs to consumers due to frozen domestic fuel prices.

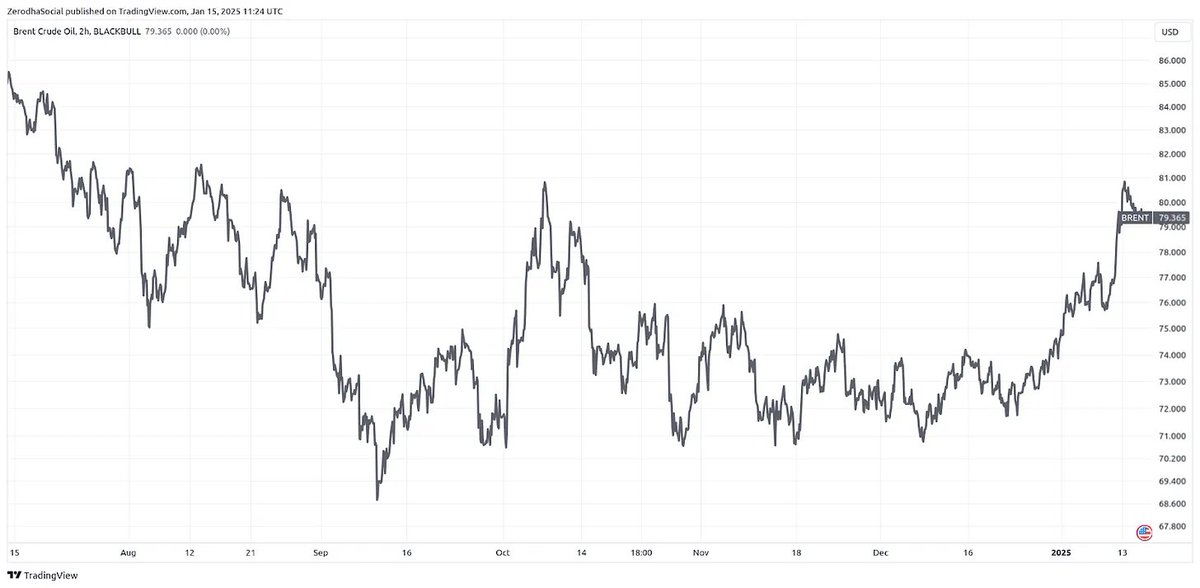

In China, refiners are also shifting to other sources, such as Africa and the Middle East. This growing demand for alternative crude is pushing up spot prices, adding more pressure to global oil markets. Brent crude has already risen above $81 per barrel, reflecting the impact of these disruptions.

The sanctions are reshaping global oil flows yet again. For Russia, losing access to its shadow fleet could jeopardize its ability to maintain export volumes. For countries like India and China, higher crude prices mean inflationary pressures, rising transportation costs, and potential fiscal challenges. The West, meanwhile, is betting that these new measures will force Moscow to confront the economic costs of its war-driven policies.

As the sanctions continue to bite, the stakes remain high for everyone involved. Will Russia find a way to adapt, or will the U.S. strategy finally achieve its goal of choking off Moscow’s war machine? The next few months will be critical in determining the outcome of this economic warfare.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's Daily Brief. You can watch the episode on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts. All links here:

thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/us-sanctions…

thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/us-sanctions…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh