Actually, the US government has been involved with clothing in a few ways. The results have been glorious. Let me show you. 🧵

https://twitter.com/Gramma_Barbie/status/1890534168913731882

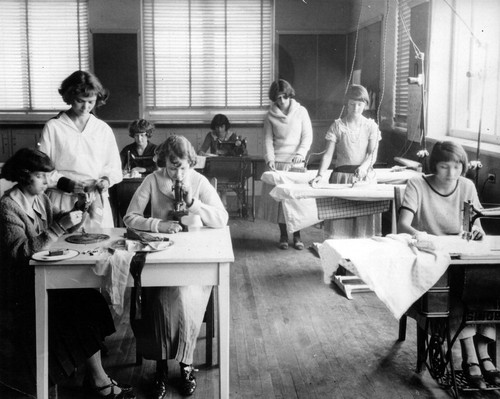

During the early 20th century, when labor was more divided by gender, the US Dept. of Agriculture organized youth clubs orientated around developing certain skills. Chief among them were clothing clubs, which taught young girls how to cut, mend, and sew clothing.

In her book The Lost Art of Dress, historian Linda Przybyszewski estimates that more than 324,000 girls participated in clothing clubs (cooking clubs were a distant second with half as many members). The US gov also funded home economics education, which taught similar skills.

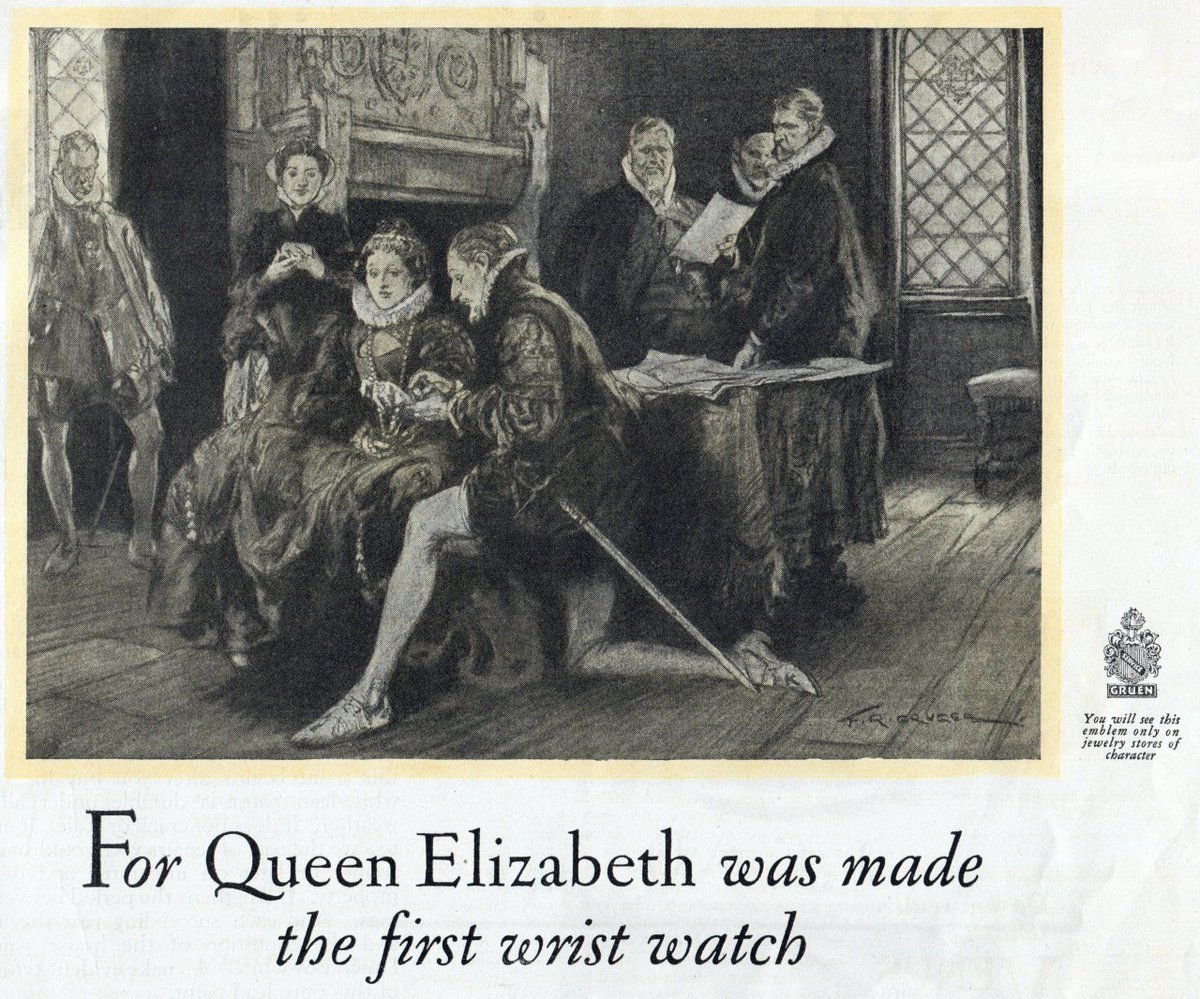

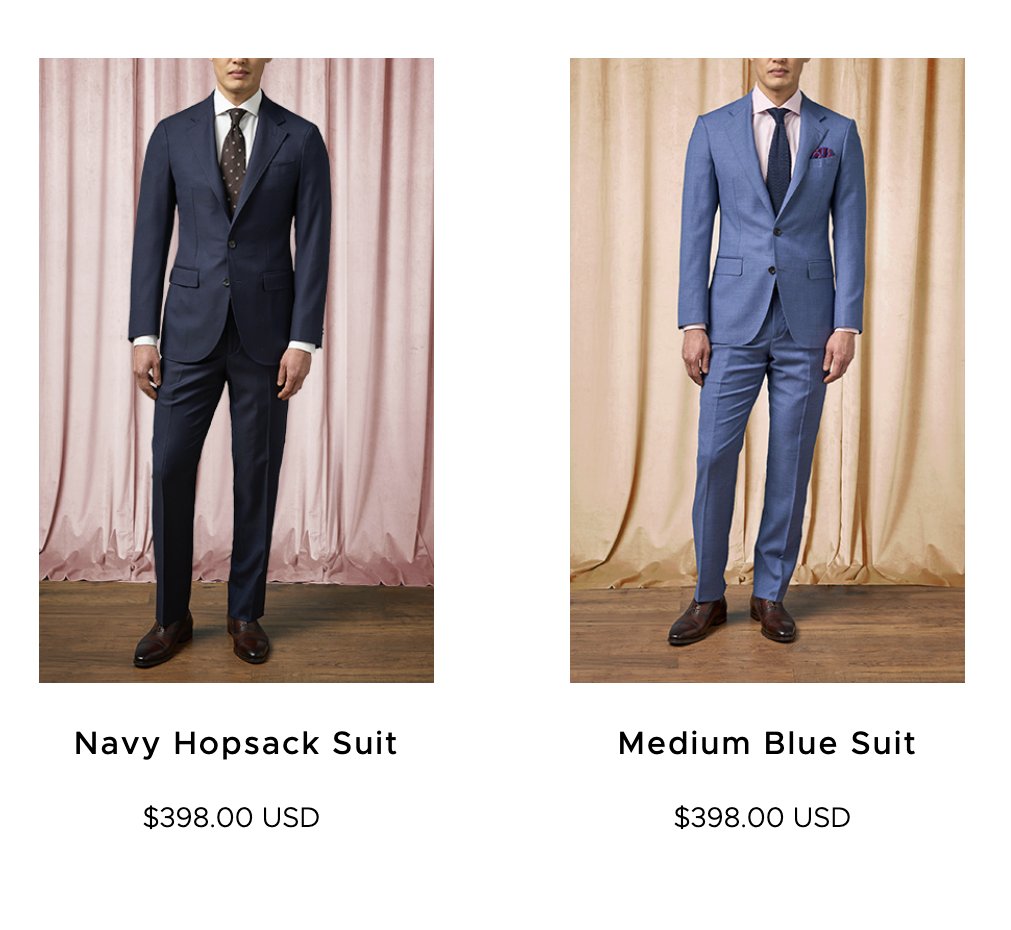

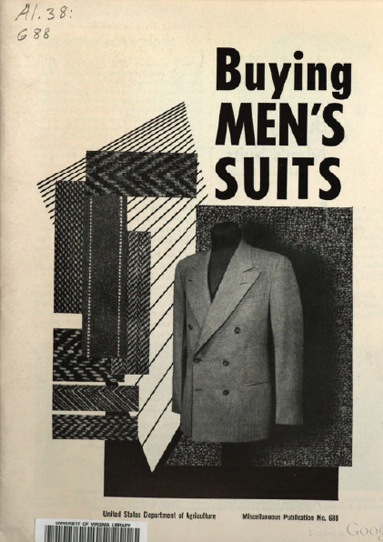

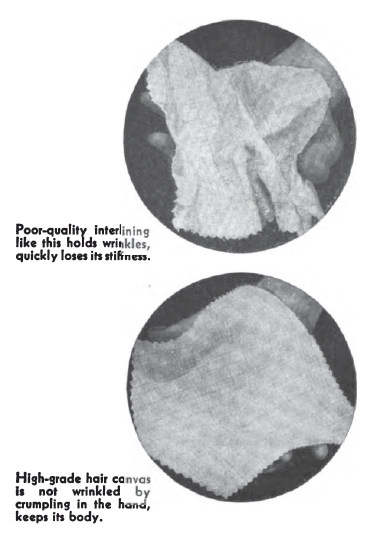

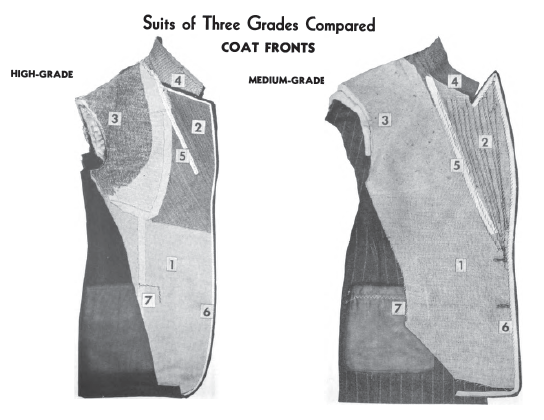

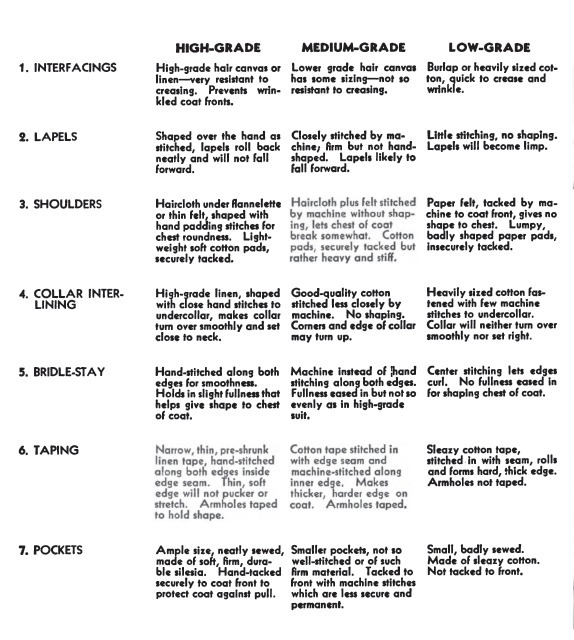

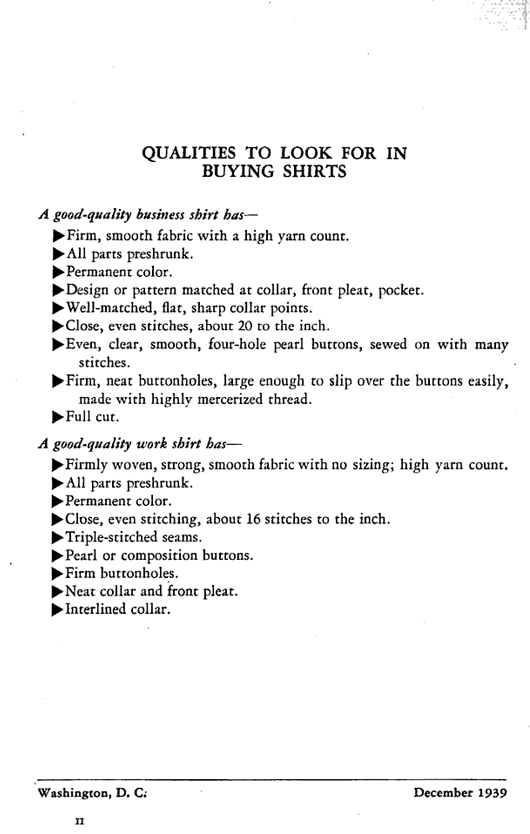

The US Dept of Agriculture also published guides on how to spot quality clothing and take care of things you own. The guides were surprisingly sophisticated. This guide on men's suits talked about fabrics like gabardine, serge, covert, and tropical worsted.

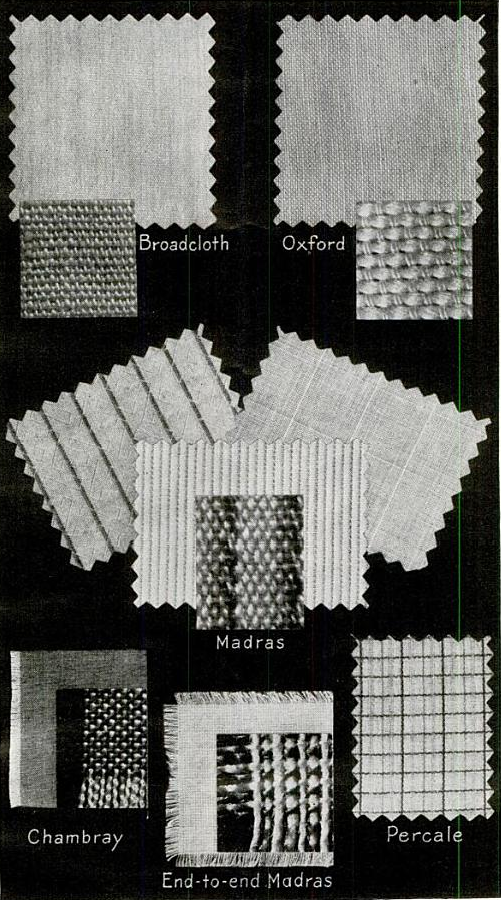

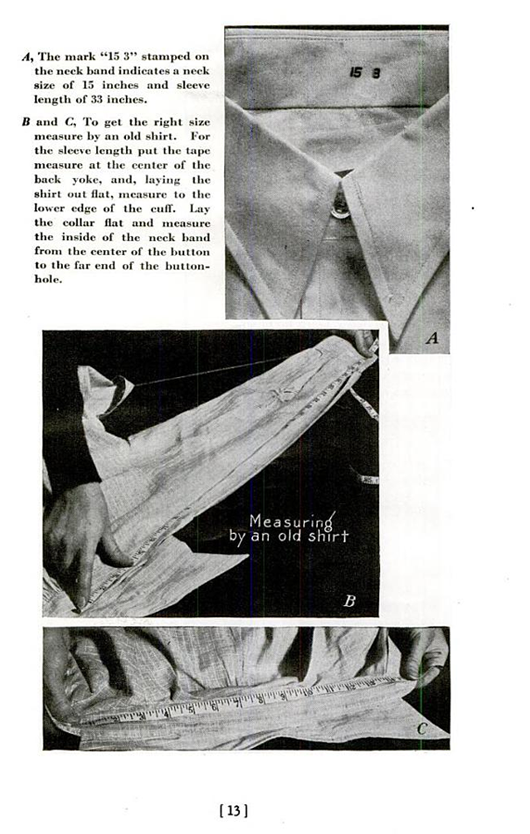

Here is the guide for men's shirts (they recommended that you buy a full-cut shirt, not a slim fit). Note the page showing different weaves: broadcloth, oxford, chambray, etc. You don't even get this kind of info in men's fashion magazines nowadays.

It's hard to overstate the impact of this education. Not only were consumers more informed, but people at home knew how to mend clothing or repurpose things they no longer wore. There was a *culture* of repair, such that people bought and kept things for longer.

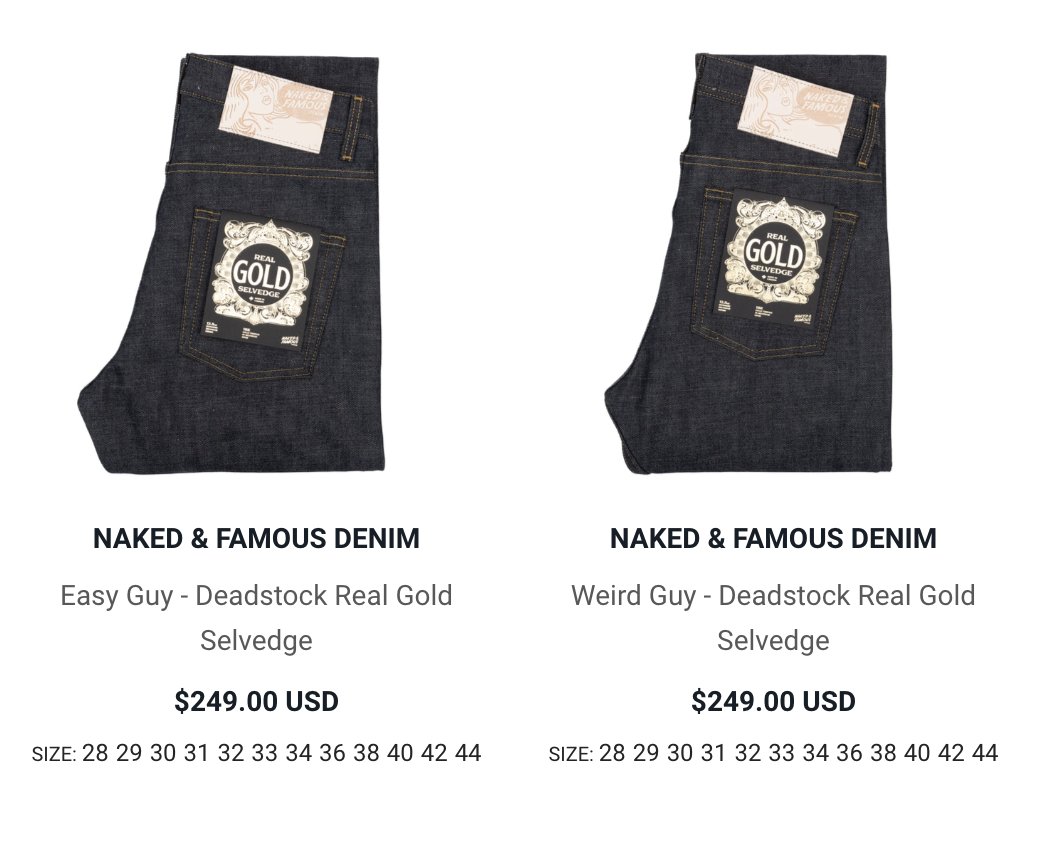

I recently spoke with fashion critic and StyleZeitgeist founder Eugene Rabkin, who lamented the "deskilling of consumers." We all know about the deskilling of workers—the way automation or division of labor can deskill workers such as craftsmen, putting them on an assembly line.

Rabkin believes a similar thing has happened to consumers. Many today are less educated about how to buy and care for quality goods. Privately-owned media enterprises have done a poor job of filling in this space, as they focus on trends, celebrities, and industry news.

"But Derek," you say, "I think the original poster was talking about the government *making* clothes. Surely, they're bad at that!"

Not true. In fact, much of menswear can be traced back to the US Dept of Defense.

Not true. In fact, much of menswear can be traced back to the US Dept of Defense.

After all, it was the US military that came with the A-1 and A-2 bombers; MA-1 flight jackets; B-3 and B-6 shearlings; M43, M51, and M65 Army jackets; N-3B and M-51 parkas; and naval-issued peacoats. These things are still available in thrift shops today bc they're so well made.

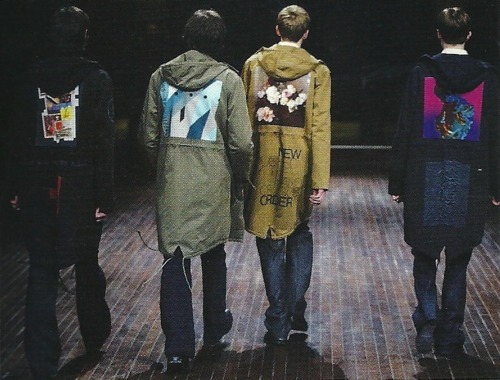

These designs have also inspired countless designers, who reinterpret them in different materials, details, and designs. Such remixes can be cool ... but the originals are also great and widely available at military surplus depots and thrift shops.

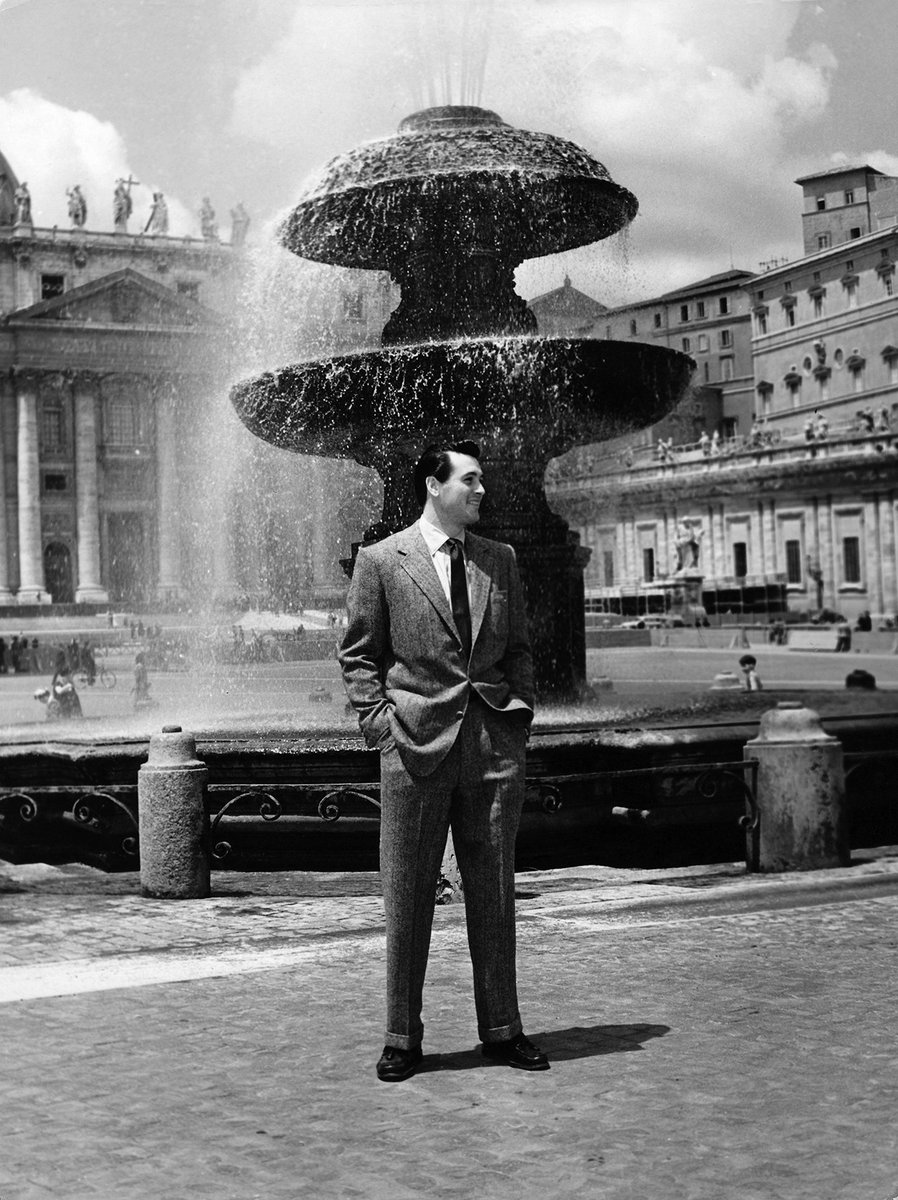

In some ways, the quality of military clothing has deteriorated with time, as technology makes it possible to cut corners. For instance, 1950s and '60s Army chinos and fatigues were made from pure cotton, which made them more breathable and allowed them to fade in nicer ways.

Starting in the 1980s, the US gov switched to a poly blend to save money. Unfortunately, this fabric doesn't develop the nice fades you see below. They also changed the cut, so the pants fit more like Dickies, rather than the wider pre-1980s silhouette.

When it comes to the US government's involvement in clothing, perhaps the most important has been the creation of American jobs. US gov contracts still require that clothes be made at US factories. This has helped prop up plants like the former Hickey Freeman factory.

My point: the state can be used for good. It's not true that the private sector is always better. A lot of development and even capitalist structures required incredible state involvement. I recommend checking out these two books.

But on the matter of clothing—which is not unlike other areas of our lives—the government has been a positive force in ways that often goes unrecognized. I bet if you look through your closet now, you will find some things that some government helped develop.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh