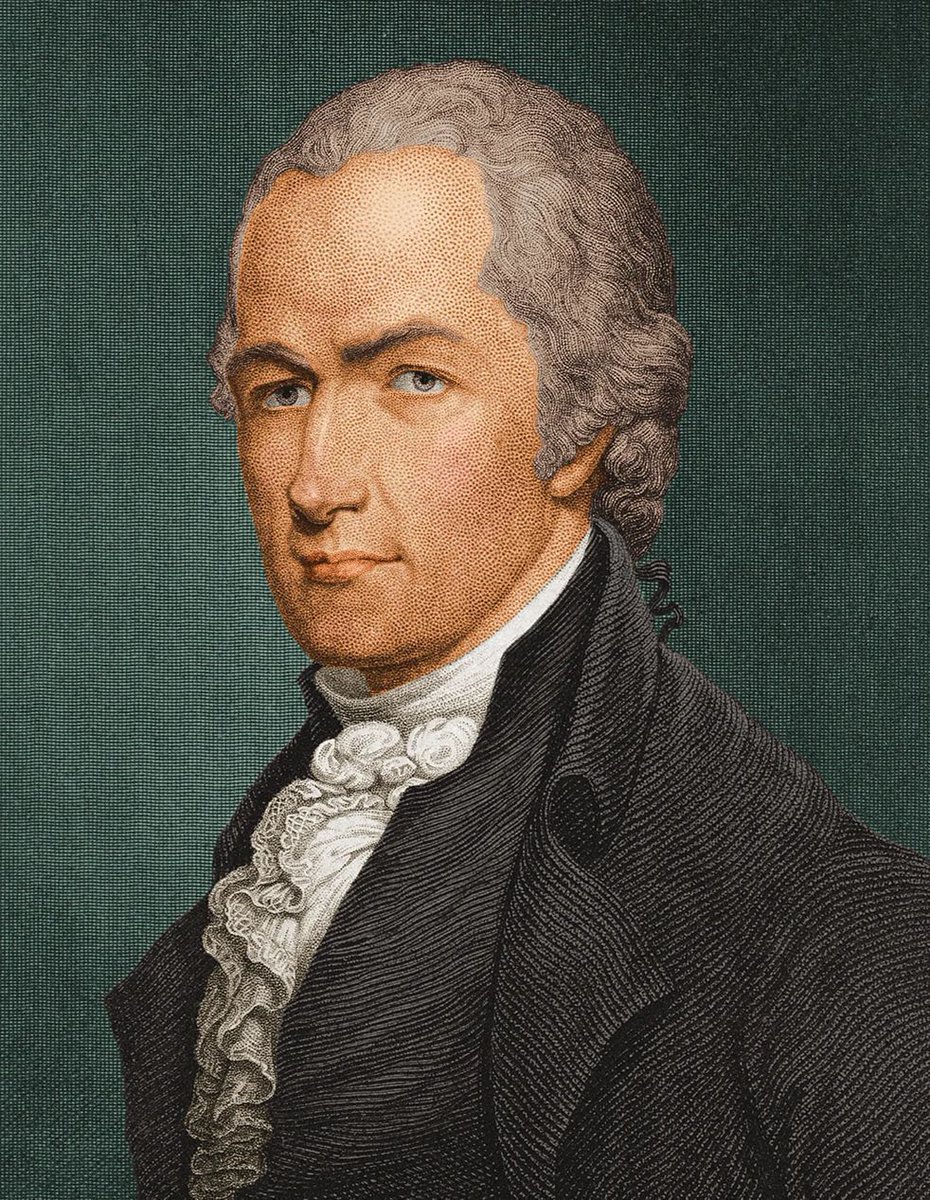

Alexander Hamilton argued in 1787 that the United States should resemble a monarchy.

It might sound like heresy to modern Americans, but his idea had some merit.

Here’s how it would’ve worked🧵

It might sound like heresy to modern Americans, but his idea had some merit.

Here’s how it would’ve worked🧵

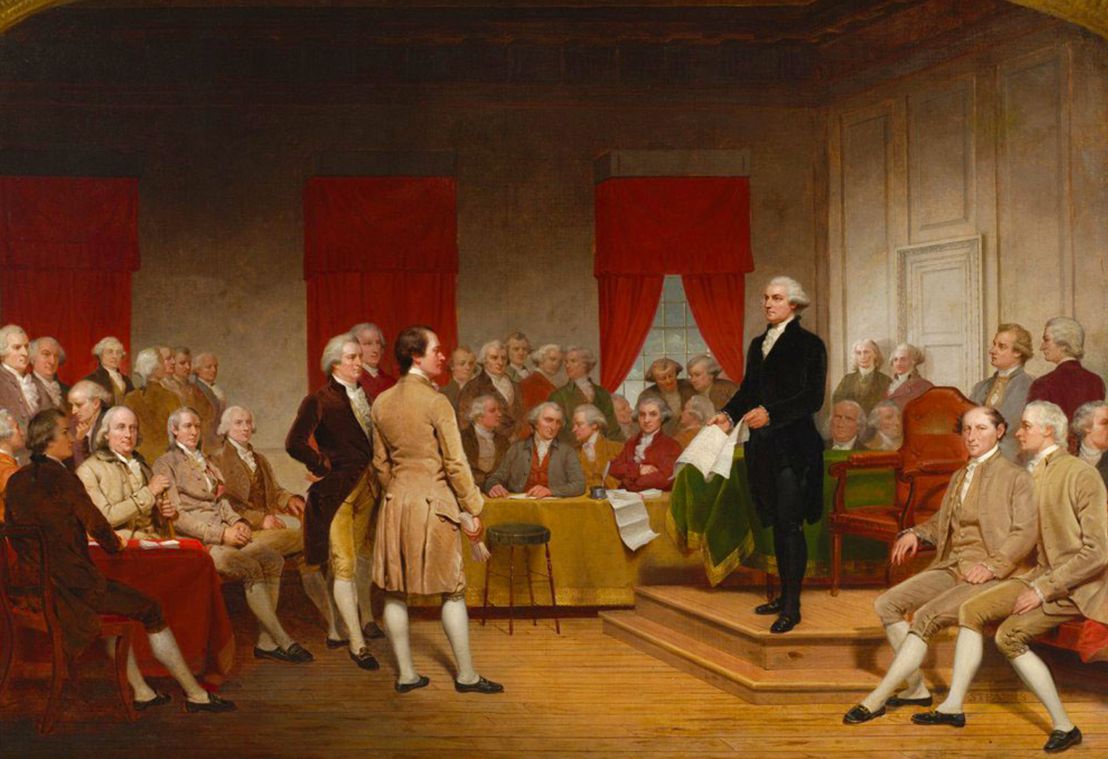

Hamilton gave a long and impassioned speech at the constitutional convention in favor of his position, nevertheless it was resoundingly voted down in favor of the presidential system the US has today.

But what did Hamilton advocate for exactly?

But what did Hamilton advocate for exactly?

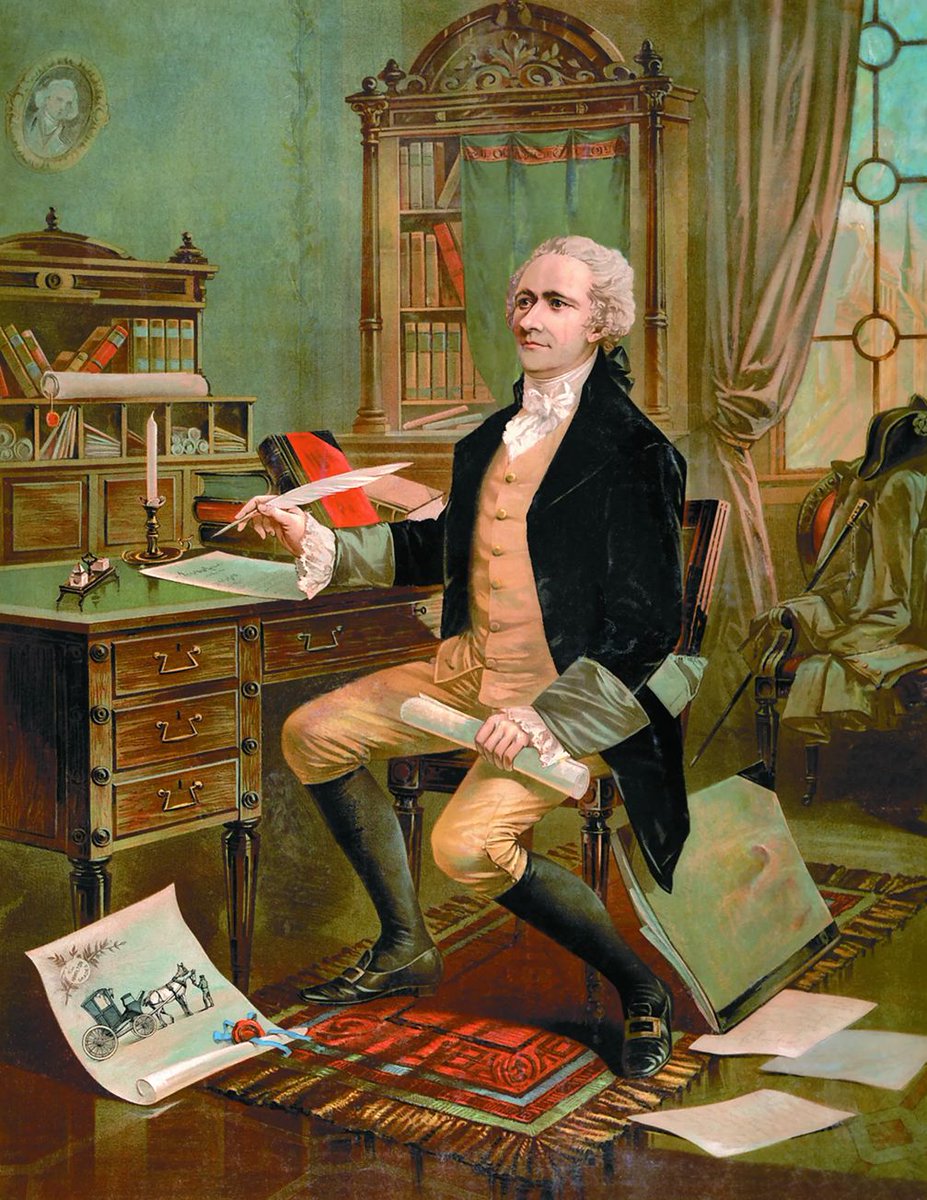

A Revolutionary army captain who fought fiercely against the British, Hamilton was actually sympathetic to the British system of government.

Specifically, he admired its strong monarch, and his proposed system was likely influenced by his understanding of Britain’s government.

Specifically, he admired its strong monarch, and his proposed system was likely influenced by his understanding of Britain’s government.

But unlike the British monarchy, where power was transferred via bloodline, Hamilton’s leader—still called the “president”—would be an elected figure.

After election the president would retain power for life as long as misconduct did not force an impeachment by congress.

After election the president would retain power for life as long as misconduct did not force an impeachment by congress.

In this system, the president would have a broad swathe of powers. He could veto any law, make treaties, and appoint state governors.

He would wield enough power domestically to resist foreign influence, while the possibility of impeachment would prevent tyrannical rule.

He would wield enough power domestically to resist foreign influence, while the possibility of impeachment would prevent tyrannical rule.

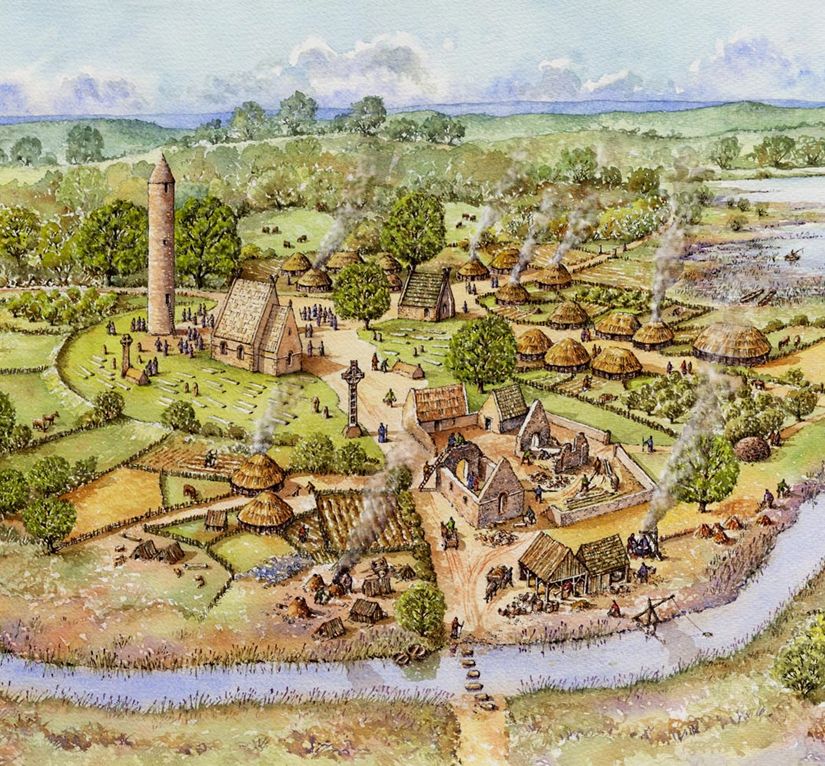

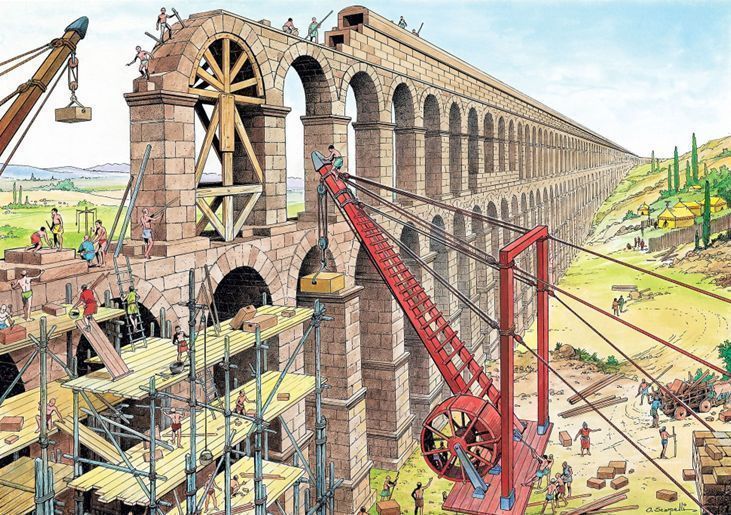

Hamilton’s idea of an elected monarch was not new. As a well-educated man, he would’ve been familiar with the system of government as it was used throughout history—in ancient Rome before the republican era, and most notably the Holy Roman Empire.

In the Holy Roman Empire, the emperor was elected by a small body of the most powerful princes, or “prince-electors.” Once a leader was selected, the coronation of the emperor took place in either Aachen or Frankfurt, whereupon the elected prince would become monarch.

The long success of the Holy Roman Empire, which was still intact during the time of the constitutional convention, was a testament to the strength of the system.

But why did Hamilton believe this system would work for the US?

But why did Hamilton believe this system would work for the US?

Hamilton believed that presidents who served only short terms were more likely to use their presidency to benefit themselves since they would soon return to being a private citizen.

By having a lifelong term, presidents wouldn’t worry about their lives after service and would focus on promoting the best interests of the nation—the president’s interests and the nation’s interests would naturally coincide.

Though Hamilton was a firm believer in his system, once it was voted down, he put his personal beliefs aside and supported Madison’s Virginia Plan which served as the foundation of the US constitution.

It’s interesting to think that the fundamental structure of the presidency could have been very different if Hamilton had his way.

The idea of an elective monarchy is an intriguing concept that causes one to rethink the nature of monarchy itself.

The idea of an elective monarchy is an intriguing concept that causes one to rethink the nature of monarchy itself.

Modern ears often reflexively associate monarchy with tyranny, but in an elective monarchy, the people still have a say in who governs them.

What do you think—is it a good system? Should the US have been an elective monarchy?

What do you think—is it a good system? Should the US have been an elective monarchy?

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to join the mission of promoting western tradition, kindly repos the first post (linked below) and consider following: @thinkingwest

https://twitter.com/thinkingwest/status/1895107120271442096

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh