To what extent was knowledge and transmission of the reading traditions dependent on written works and/or notebooks rather than the semi-oral process of reciting the Quran to a teacher?

In the transmission of Ibn Bakkār from Ibn ʿĀmir the written transmission is very clear. 🧵

In the transmission of Ibn Bakkār from Ibn ʿĀmir the written transmission is very clear. 🧵

The reading of the canonical Syrian reader Ibn ʿĀmir is not particularly well-transmitted. The two canonical transmitters Ibn Ḏakwān and Hišām are several generations removed from Ibn ʿĀmir, and Ibn Ḏakwān never had any students who recited the Quran to him.

Al-Dānī preserves three other transmission paths besides the canonical paths, although all of them only through a single ʾisnād.

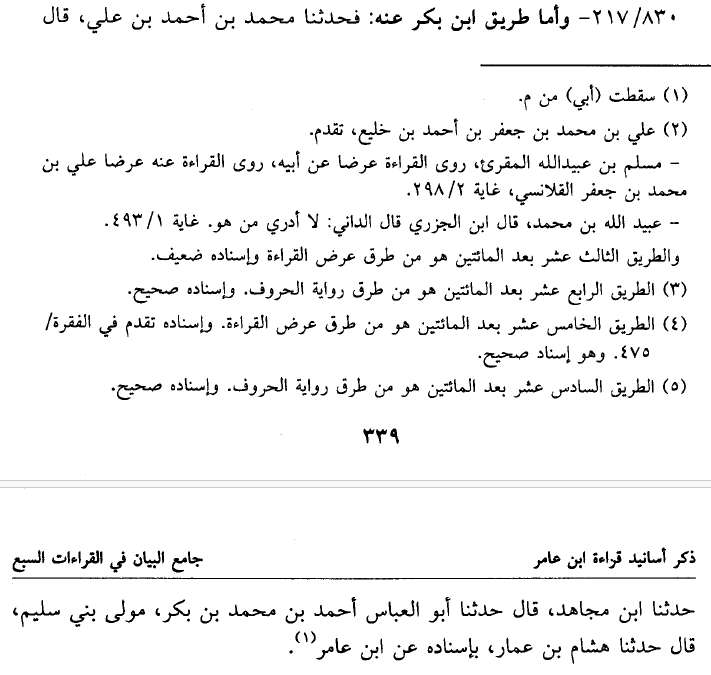

The one we are interested in here is Ibn Bakkār's transmission. The ʾisnād is cool, it's transmitted through the fanous exegete Ibn Ǧarīr al-Ṭabarī!

The one we are interested in here is Ibn Bakkār's transmission. The ʾisnād is cool, it's transmitted through the fanous exegete Ibn Ǧarīr al-Ṭabarī!

Al-Dānī makes a strict distinction between two types of transmission tilāwah and riwāyah.

tilāwah ʾisnaḏs use the formula: qaraʾtu (al-qurʾān kullahū) bihā ʿalā fulān "I recited (the whole Quran) according to it to so-and-so.

The formula shows what this transmission type was.

tilāwah ʾisnaḏs use the formula: qaraʾtu (al-qurʾān kullahū) bihā ʿalā fulān "I recited (the whole Quran) according to it to so-and-so.

The formula shows what this transmission type was.

riwāyah ʾisnāds use the formula: ḥaddaṯanā fulān "So-and-so told us". From that formulation it is not directly clear what exactly was being "told" or how that was being transmitted.

The Ibn Bakkār ʾisnād is a riwāyah ʾisnād.

The Ibn Bakkār ʾisnād is a riwāyah ʾisnād.

However, by looking at how Ibn Bakkār's transmission is cited in the Ǧāmiʿ al-Bayān, what this type of transmission was like becomes much clearer: it clearly involved the transmission of written material, which appears to have required largely personal interpretation by al-Dānī.

How can we tell? Let's look at some reports:

"Ibn Bakkār said, from ʾAyyūb from Yaḥyā from [Ibn ʿĀmir] that ʾa-ʾanḏartahum (Q2:6) is with two hamzahs by shape (šaklan), without explanation (dūna tarǧamah), and this is analogously applied to the whole category."

"Ibn Bakkār said, from ʾAyyūb from Yaḥyā from [Ibn ʿĀmir] that ʾa-ʾanḏartahum (Q2:6) is with two hamzahs by shape (šaklan), without explanation (dūna tarǧamah), and this is analogously applied to the whole category."

So what does this mean? Ibn Bakkār is supposed to have said this word is with two hamzahs "in shape without explanation".

What al-Dānī means to say is that the transmission of Ibn Bakkār that he is looking at has written this word out, using the shape of the hamzah sign.

What al-Dānī means to say is that the transmission of Ibn Bakkār that he is looking at has written this word out, using the shape of the hamzah sign.

In qirāʾāt works it is typical to not rely on spelling of a word only. A copyist too easily could forget about copying every single sign that is important. The moment you forget to, the word becomes unintelligible. Therefore, authors are often very explicit:

They will *explain* (= tarǧamah) how a specific word is different, e.g. by saying bi- hamzatayn "with two hamzahs" as al-Dānī does in his description.

Al-Dānī's source for Ibn Bakkār lacks this explanation, it onyl has the shapes of two hamzahs, and he dutifully tells us this.

Al-Dānī's source for Ibn Bakkār lacks this explanation, it onyl has the shapes of two hamzahs, and he dutifully tells us this.

It is in fact a good thing, even today, that qirāʾāt works tend to be verbose about this, because Arabic printing houses not infrequently "helpfully" replace all quranic citations with Ḥafṣ, and thus the šakl frequently doesn't match the qirāʾah.

(e.g. Ibn Ġalbūn's ʾiršād...)

(e.g. Ibn Ġalbūn's ʾiršād...)

But one thing becomes clear from al-Dānī's wording here: all he has to go on is how it is spelled (which is not necessarily reliable). There is no further explanation, no oral tradition that helps him decide what exactly is meant. This is purely written transmission.

A similar issue shows up again:

"And Ibn Bakkār from Ibn ʿĀmir transmitted: ʾa-ʾiḏā kunnā and ʾaʾimata l-kufr"with two hamzahs, in shape (šaklan) without an explanation (min ġayri tarǧamah)"

And ʾAbū Ṭāhir said: "I specified it in my book with a maddah between two hamzahs".

"And Ibn Bakkār from Ibn ʿĀmir transmitted: ʾa-ʾiḏā kunnā and ʾaʾimata l-kufr"with two hamzahs, in shape (šaklan) without an explanation (min ġayri tarǧamah)"

And ʾAbū Ṭāhir said: "I specified it in my book with a maddah between two hamzahs".

On discussing Q8:59 we see there is disagreement among the readers whether one reads ʾinnahum orʾannahum. "The rest read it with kasr on the hamzah, and thus transmitted Ibn Bakkār from Ibn ʿĀmir by shape, not by explanation." -- the hamzah apparently written below the ʾalif.

These references to transmissions to written šakl "shape" are not unique to the transmission of Ibn Bakkār (especially common for Ibn ʿĀmir). For example: "In his book on the authority of ibn Ġalbūn [...] from Hišām ʾanbiʾhum أنبئهم with a yāʾ with hamzah in shape"

"Everybody read raġaban wa-rahaban with two fatḥahs except what [...] is transmitted for Hišām from Ibn ʿĀmir with ḍammah on both words.

Ibn Ġalbūn [...] from Hišām said: رغبا ورهبا is heavy (muṯaqqal = bisyllabic stem)"

Ibn Ġalbūn [...] from Hišām said: رغبا ورهبا is heavy (muṯaqqal = bisyllabic stem)"

This wording is ambiguous, muṯaqqal doesn't tell us the quality of the vowel. Could be raġaban wa-rahaban OR ruġuban wa-ruhuban. So al-Dānī adds: in my book (copy of Ibn Ġalbūn's book?) there is a fatḥah on the hāʾ and ʿayn in shape (šaklan), which excludes ruġuban wa-ruhuban.

A final one: "Ibn ʿĀmir read wa-ḫuḍrun wa-ʾistbraqinm except for Ibn Bakkār;

In a riwāyah transmission of Hišām: ḫuḍrVn carries tanwīn, wa-ʾistabraqun with rafʿ (u vowel) and tanwīn. He did not mention anything about ḫuḍrVn other than tanwīn. ...

In a riwāyah transmission of Hišām: ḫuḍrVn carries tanwīn, wa-ʾistabraqun with rafʿ (u vowel) and tanwīn. He did not mention anything about ḫuḍrVn other than tanwīn. ...

"But in the source that I have, there is the sign of the rafʿ in shape on the rāʾ" (thus suggesting ḫuḍrun)

Al-Dānī is clearly working with written texts, and when there is no explicit wording, he simply relies on the spelling and reports it.

Al-Dānī is clearly working with written texts, and when there is no explicit wording, he simply relies on the spelling and reports it.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh