India launched Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes to become a manufacturing powerhouse. But four years later, a recent report shows they've missed almost two-thirds of their targets, with manufacturing's share in GDP declining instead of growing.

Let’s break it down 🧵👇

Let’s break it down 🧵👇

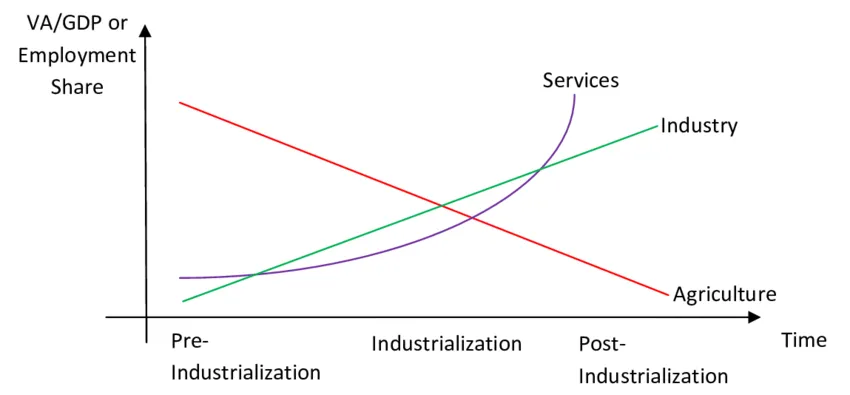

Manufacturing has a unique impact on the economy. Research shows that manufacturing jobs create 2.3 times more indirect employment than services. A 10% rise in manufacturing cuts poverty 2.1 times faster than a similar rise in services.

A 1% increase in manufacturing’s GDP share can boost economic growth by 0.5–0.7% in low and middle-income countries.

A 1% increase in manufacturing’s GDP share can boost economic growth by 0.5–0.7% in low and middle-income countries.

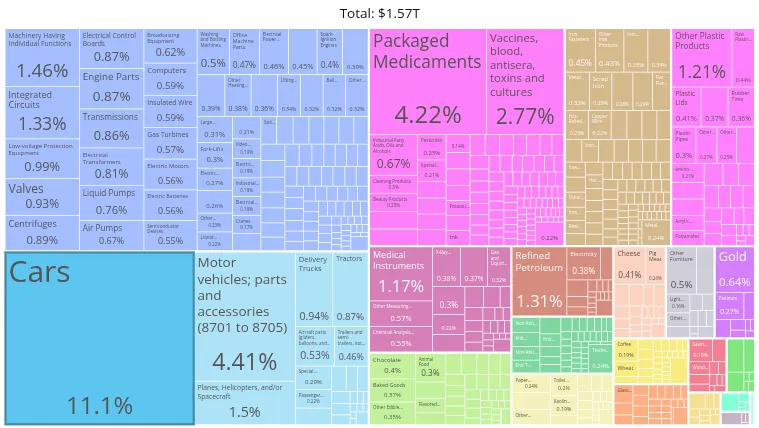

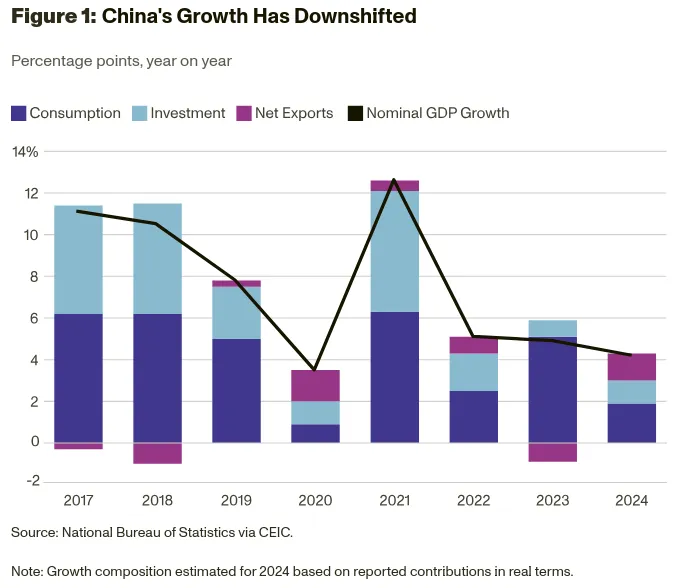

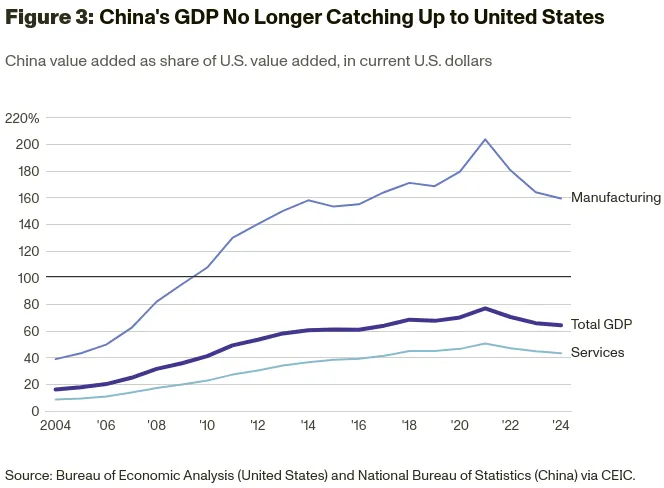

Without a strong manufacturing base, India depends on imports, especially from China. This weakens our economy and puts constant pressure on our trade balance.

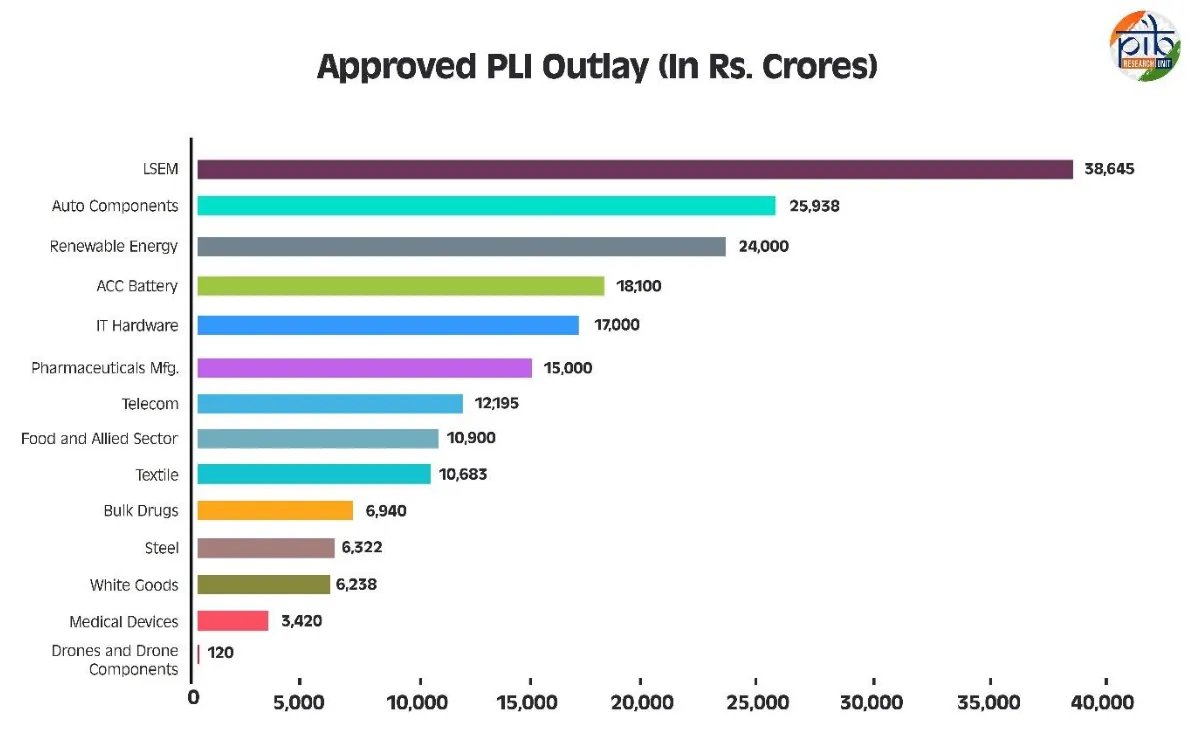

In November 2020, the government launched PLI under ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ to fix these issues. It covered 14 sectors with ₹1.97 lakh crore in incentives. The plan was to drive $500 billion in production, create jobs, and push manufacturing’s share to 25% of GDP by 2025.

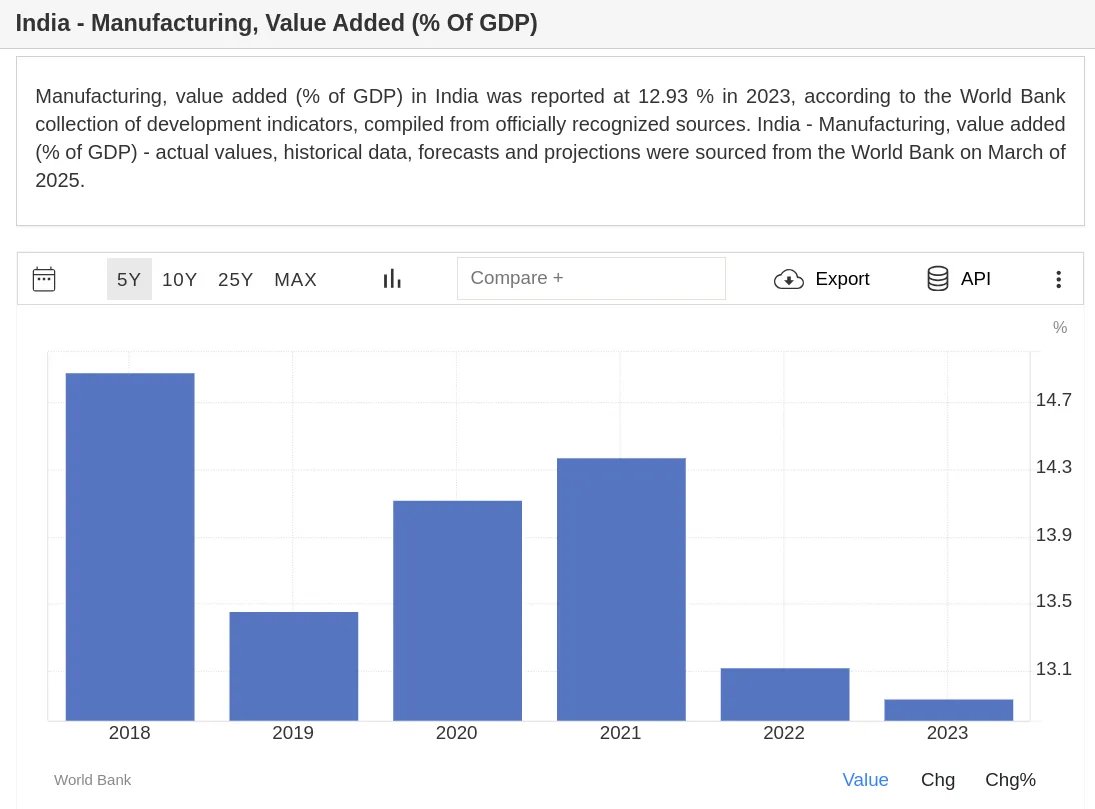

The reality has been very different. As of October 2024, firms in the PLI program have produced just $151.93 billion worth of goods—only 37% of the target. Incentive payouts have been slow, with only $1.73 billion disbursed so far, less than 8% of the total allocation.

Instead of growing, manufacturing’s share of the economy has shrunk, falling from 14.1% to 12.9% since PLI was launched.

Not everything has failed, though. Two sectors—electronics manufacturing services and pharmaceuticals—have done well. Mobile phone production jumped 63% to $49 billion last year, and Apple now manufactures its latest iPhones in India. Pharma exports have nearly doubled in a decade to $28 billion.

But that’s just two out of fourteen sectors. Others are nowhere close to hitting their targets. Earlier, there was talk of expanding PLI to more industries. Now, that plan is off the table. The government has hinted that if existing sectors can’t meet their targets, the program could be scaled back.

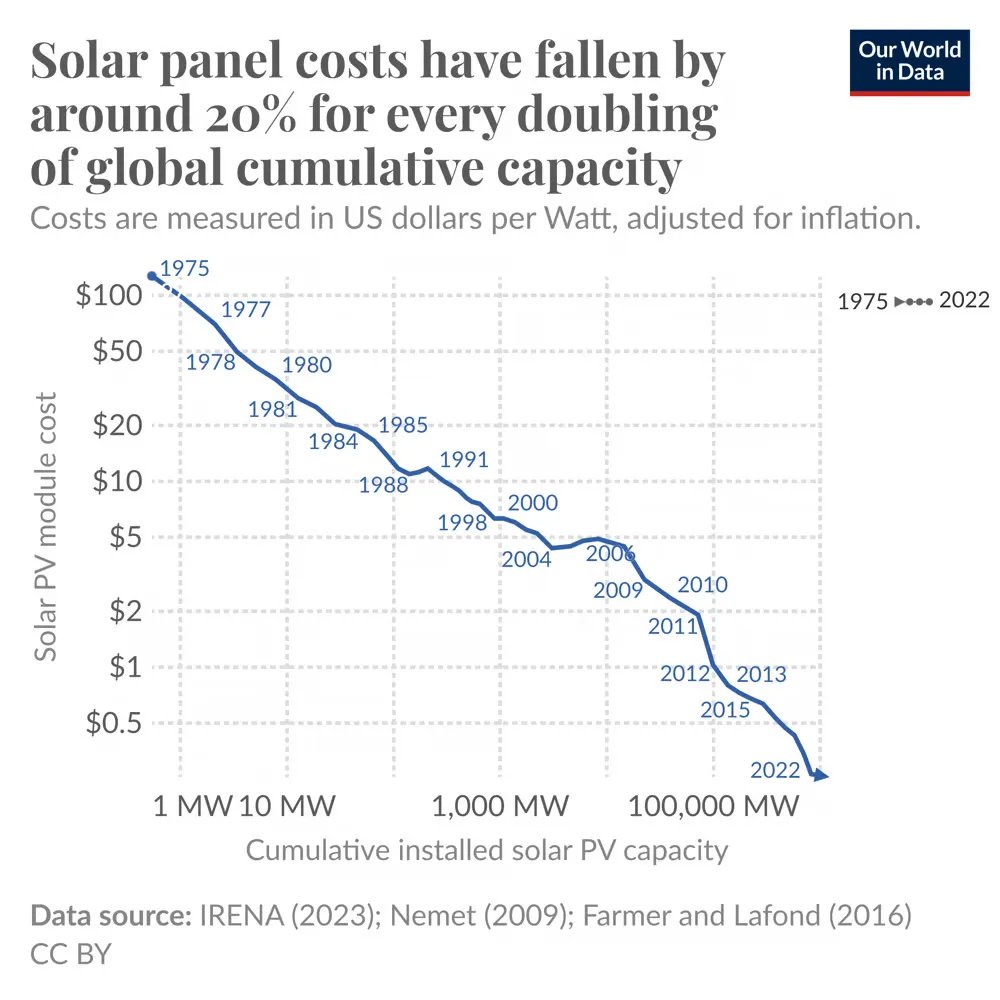

Why has PLI struggled? First, overambitious targets. Many companies set sky-high expectations they can't meet. The solar industry is a perfect example—eight out of twelve firms are on track to miss targets, including big names like Reliance, Adani, and JSW. In steel, fourteen of fifty-eight approved projects have been withdrawn for lack of progress.

Delays have been another issue. Many firms only got selected for PLI incentives in 2022, two years behind schedule. That lost momentum has been costly, especially in capital-intensive sectors like semiconductors and advanced batteries, where full-scale production hasn’t even begun.

Complex compliance requirements have made things worse. High investment thresholds, rigid sales targets, and strict domestic value-addition rules have created endless compliance headaches. Some investors would rather hold back than deal with the complexity.

PLI was meant to boost India’s manufacturing, but most of it hasn’t worked as planned. Maybe the targets were too high, maybe the process was too slow. What’s clear is that India needs a stronger manufacturing base. If PLI is the answer, it has to change because, in its current form, it’s falling short.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's Daily Brief in detail. You can watch the episode on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts. All links here: thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/weight-loss-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh