This new Linux script from THC will encrypt and obfuscate any executable or script to hide from on-disk detection. I'm going to show you how to detect it with command line tools in this thread.

github.com/hackerschoice/…

github.com/hackerschoice/…

First, it only encrypts the binary at rest on disk. It is not encrypting the running process. This will evade legacy file scanning with YARA, etc. that is unreliable on Linux and I don't recommend using. The running process has no encryption so that is our detection target.

I encrypted a netcat binary. See the directory of encrypted and unencrypted binaries? Notice the size, and also notice I gzipped the binaries. Encrypted binaries do not compress well. This is a cheap "is this encrypted or not" check.

Running netcat as a listener we see it running here in the process listing. Again, once running the encrypted protection is gone and we will focus our efforts there.

We'll got to /proc/PID directory and do a quick investigation. A simple 'ls' directory listing gives us our first clue with the weird link of the exe to memfd:. Binaries should not be running out of a memfd: socket unless they are hiding.

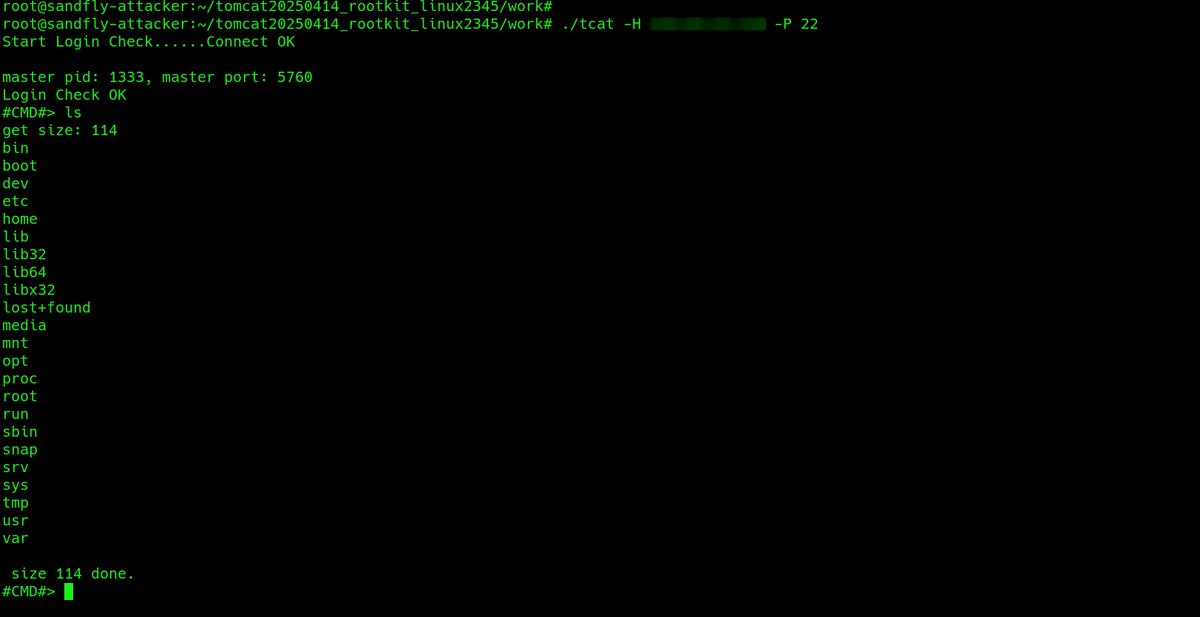

Since the running binary is not encrypted, we'll grab it from memory so we can analyze it off the host at our leisure. This is very easy even if in a memfd socket:

cp /proc/PID/exe /tmp/malicious.bin

cp /proc/PID/exe /tmp/malicious.bin

Inspect the file descriptors of a suspicious process by going to /proc/PID/fd.

With the fileless memfd attacks, the file descriptors will tell you what kind of file is being stored. A binary (ELF) file in a memfd: socket is bad news.

With the fileless memfd attacks, the file descriptors will tell you what kind of file is being stored. A binary (ELF) file in a memfd: socket is bad news.

We can see also if it's network enabled even if hiding this kind of thing in system tools like netstat/ss by looking at the /proc/PID/stack. The accept() call references are a dead giveaway it's likely a backdoor/server.

The encrypted file can also be found if you check for high entropy scripts/binaries hanging around. We have a free tool to help with this called sandfly-entropyscan.

github.com/sandflysecurit…

github.com/sandflysecurit…

The attack generates many alerts in @SandflySecurity as a process running from a memfd socket is virtually always malicious. Here's some of what we find if this tool is being used.

Overall, a neat tool to protect a payload on disk from traditional file scanning detection, but exposed once running.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh