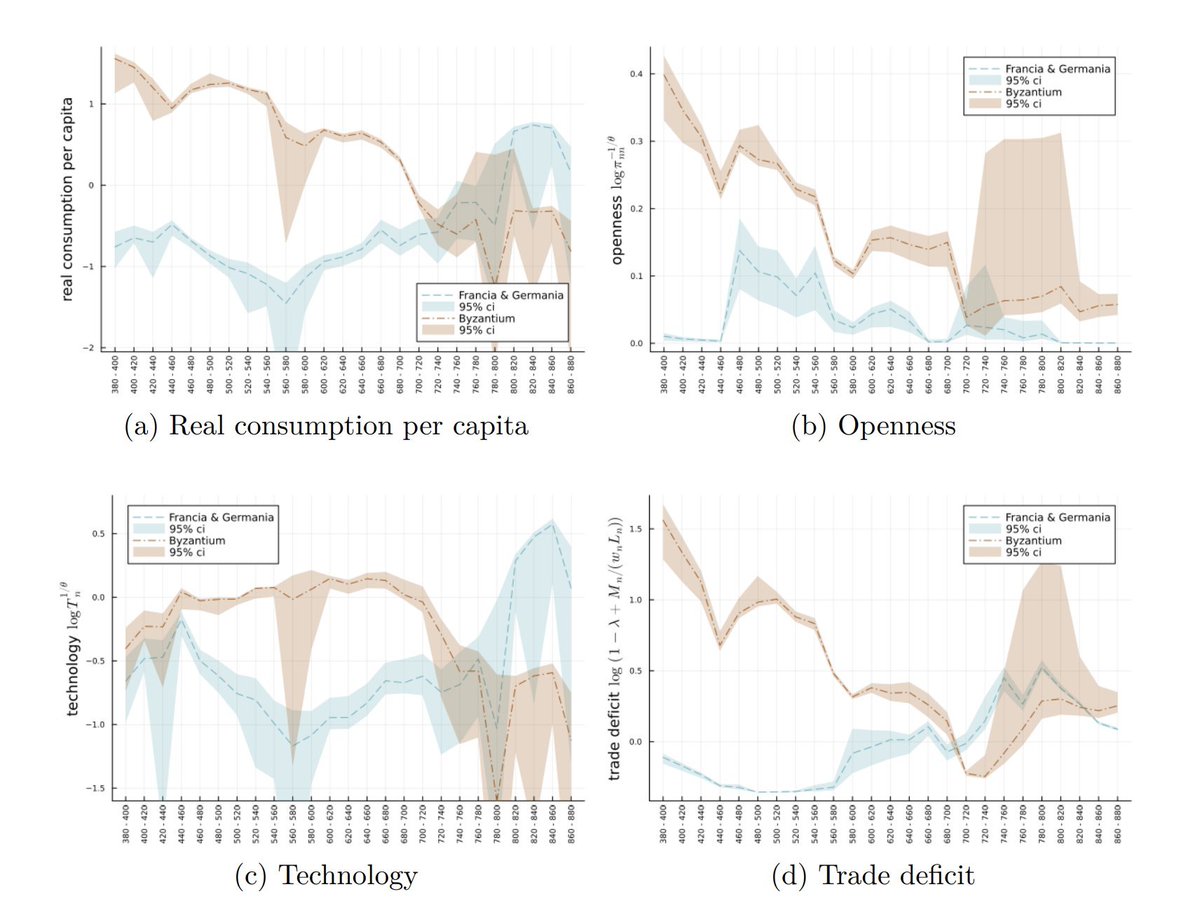

Pirenne's thesis holds that Antiquity—the period when economic activity concentrated in the Mediterranean—ended because the rise of Islam destroyed the flow of trade across it.

The decline in trade that resulted from differences in faith had profound consequences for the economic geography of Europe.

Byzantine economic activity depended on trade, and it collapsed, whereas the Frankish economy, which was never trade-dependent, transformed.

Byzantine economic activity depended on trade, and it collapsed, whereas the Frankish economy, which was never trade-dependent, transformed.

The Byzantines' minting stalled and the Arabs' and Franks' increased (perhaps partly because they were cut off from one another!), providing each of their states with divergent trends in seignorage revenues and a widening gulf in the ability to fund the government.

The decline of antiquity certainly can't be blamed entirely on the Arab conquests, but the collapse of trade resulting from that conflict of faith definitely has some interesting consequences.

Source: jmboehm.github.io/coins.pdf

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh