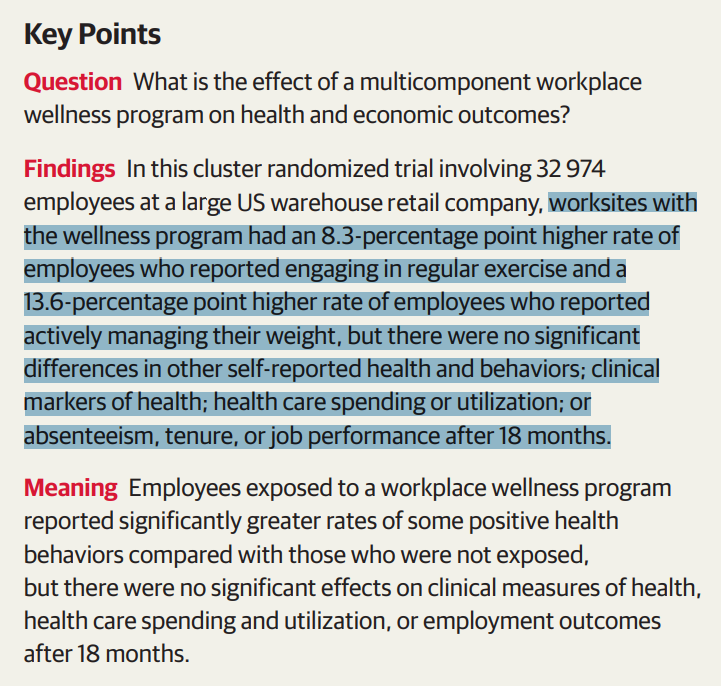

Researchers put together an incredible workplace wellness program that provided thousands of workers with paid time off to receive biometric health screening, health risk assessments, smoking cessation help, stress management, exercise, etc.

What did this do for their health?🧵

What did this do for their health?🧵

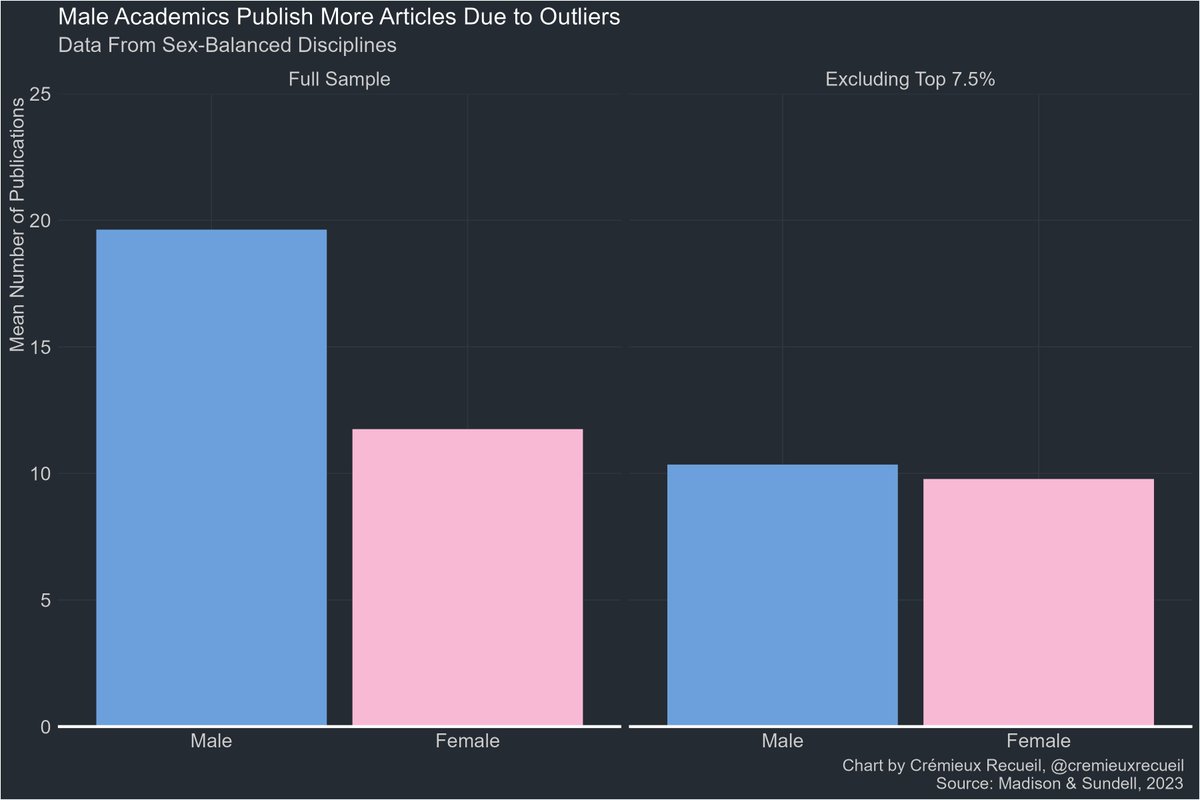

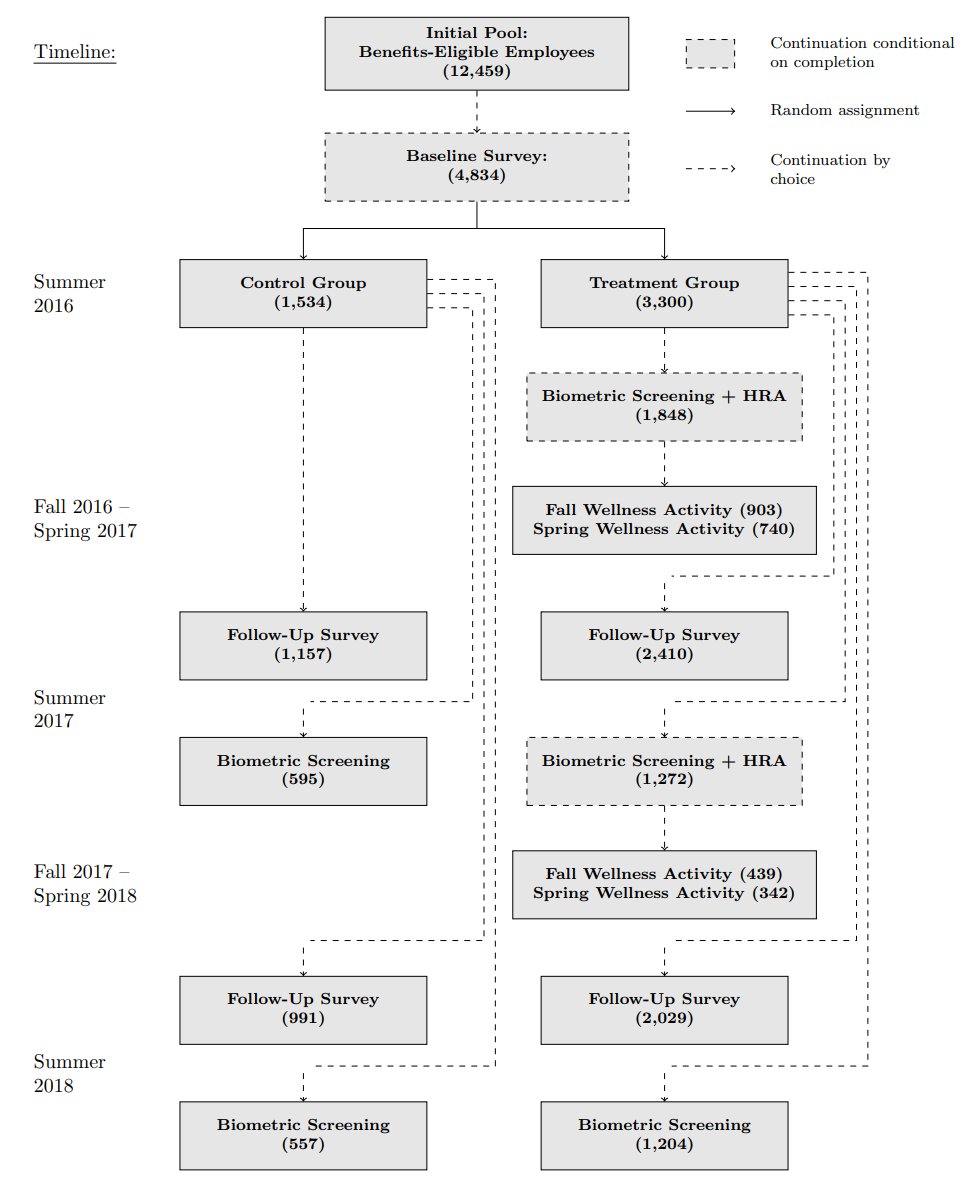

So, for starters, this program had a large sample and ran over multiple years.

Because of it, we have evidence on what people do with clinical health info, with exercise encouragement and advice, with nutritional knowledge, through peer effects, and so on.

Because of it, we have evidence on what people do with clinical health info, with exercise encouragement and advice, with nutritional knowledge, through peer effects, and so on.

Participants in the treatment group were prompted to participate with cash rewards ranging from $50 to $350.

Go to screening? Earn some money, help yourself by bolstering your knowledge about yourself and potentially improving your health.

What could be simpler?

Go to screening? Earn some money, help yourself by bolstering your knowledge about yourself and potentially improving your health.

What could be simpler?

The participants certainly seemed to think so.

The cash rewards did get more people into screenings and advising, and they even got some people moving more.

If estimates from earlier studies were to be believed, this effort should even do enough to save employers money!

The cash rewards did get more people into screenings and advising, and they even got some people moving more.

If estimates from earlier studies were to be believed, this effort should even do enough to save employers money!

But that didn't work.

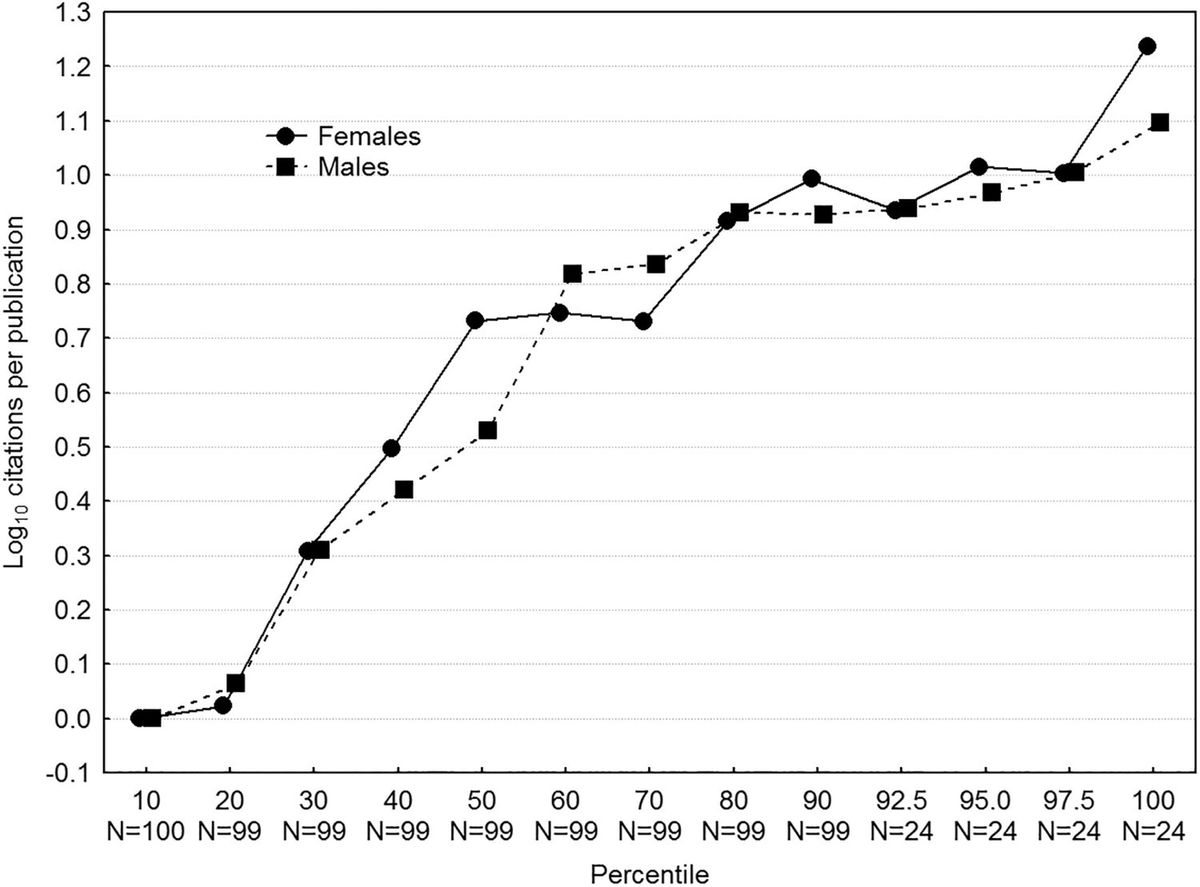

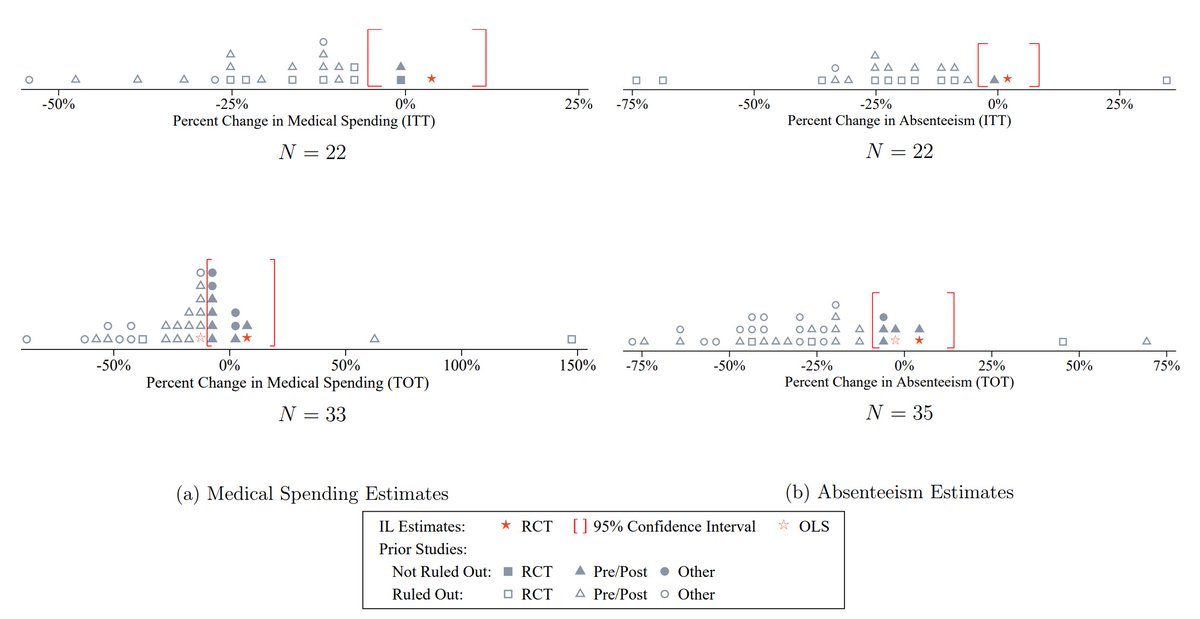

Average monthly medical spending didn't change when comparing the treatment to the control group.

Average monthly medical spending didn't change when comparing the treatment to the control group.

In fact, this study stands out in the literature, as getting nulls across basically every outcome relevant to the employer.

Health and wellness incentives and opportunities did not make people less absent or medically costly, or much else (which we'll get to).

Health and wellness incentives and opportunities did not make people less absent or medically costly, or much else (which we'll get to).

Before getting to other outcomes, we have to ask: Why trust this over other results? A few reasons:

For one, it was bigger than other studies in the experimental literature.

For two, it was preregistered, publicly archived, and independently analyzed by outside researchers.

For one, it was bigger than other studies in the experimental literature.

For two, it was preregistered, publicly archived, and independently analyzed by outside researchers.

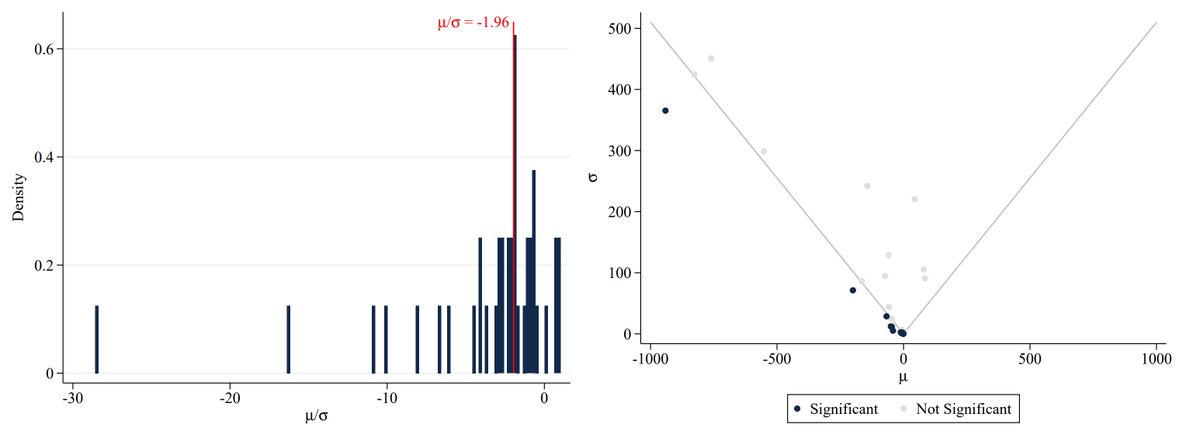

All of that on its own is really good. But what really takes the cake is that the prior literature was impacted by p-hacking and publication bias, whereas these researchers committed to publishing their results regardless.

Who do you trust more?

"We aren't financially conflicted and we'll publish regardless of what happens and of course we provide data and code."

or "p = 0.04, this program is life-changing (ignore my financial conflicts of interest :))"

I know my answer, you know my answer.

"We aren't financially conflicted and we'll publish regardless of what happens and of course we provide data and code."

or "p = 0.04, this program is life-changing (ignore my financial conflicts of interest :))"

I know my answer, you know my answer.

Now let's talk other outcomes.

Medical spending: not affected in total, admin-wise, drug-wise, office-wise, hospital-wise, or in terms of any utilization metric.

Employment and productivity: Didn't affect employee retention, salaries, promotions, sick leave, overtime, etc.

Medical spending: not affected in total, admin-wise, drug-wise, office-wise, hospital-wise, or in terms of any utilization metric.

Employment and productivity: Didn't affect employee retention, salaries, promotions, sick leave, overtime, etc.

More employment and productivity: Didn't affect job satisfaction or feelings of productivity. BUT, did affect views about management priorities on health (increased) and the likelihood of engaging in a job search (increased).

That's backfiring, potentially.

That's backfiring, potentially.

Participants failed to increase their number of gym visits, didn't participate in the IL marathon, 10k, or 5k more often, despite smoking cessation advice and help they didn't smoke less, they didn't report better health, hell, they became (marginally-significantly) fatter!

Across basically every metric, the results were null, null, and--my favorite--null.

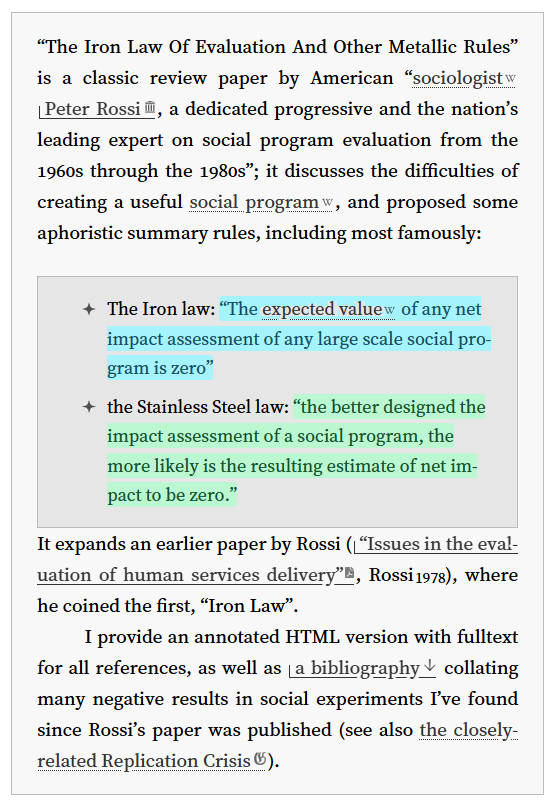

And this is what we expect with credible intervention evaluations of high-quality samples. This is so common, in fact, that it's been dubbed the "Stainless Steel Law":

And this is what we expect with credible intervention evaluations of high-quality samples. This is so common, in fact, that it's been dubbed the "Stainless Steel Law":

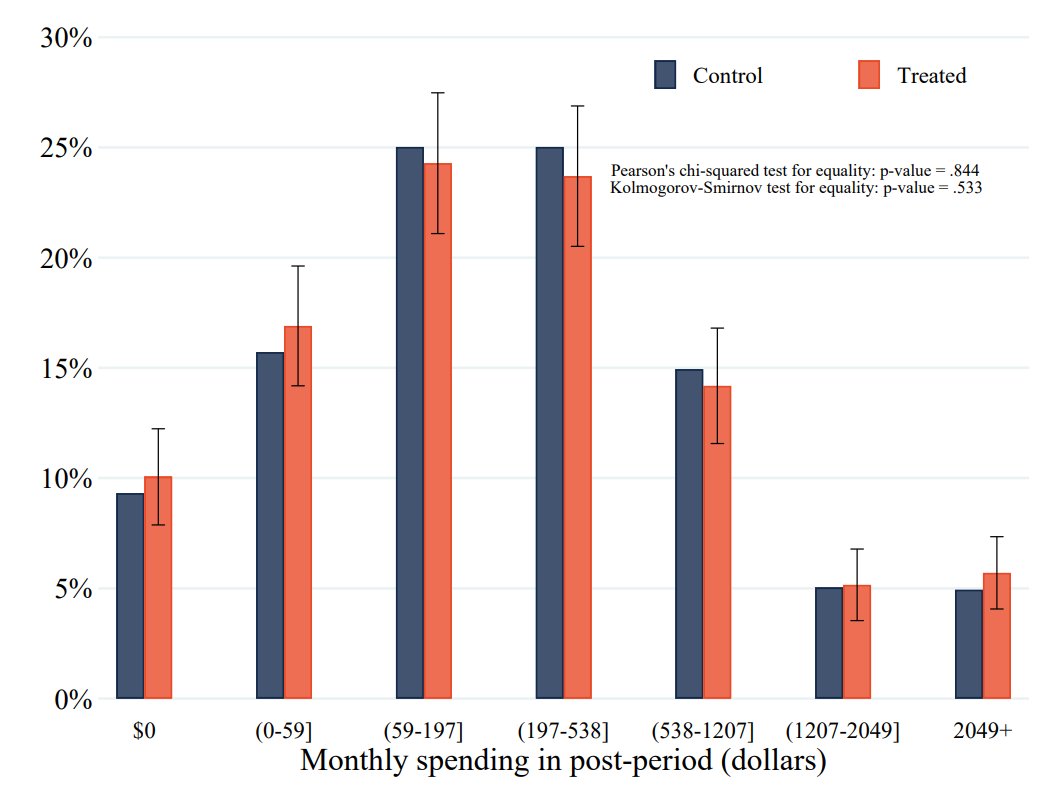

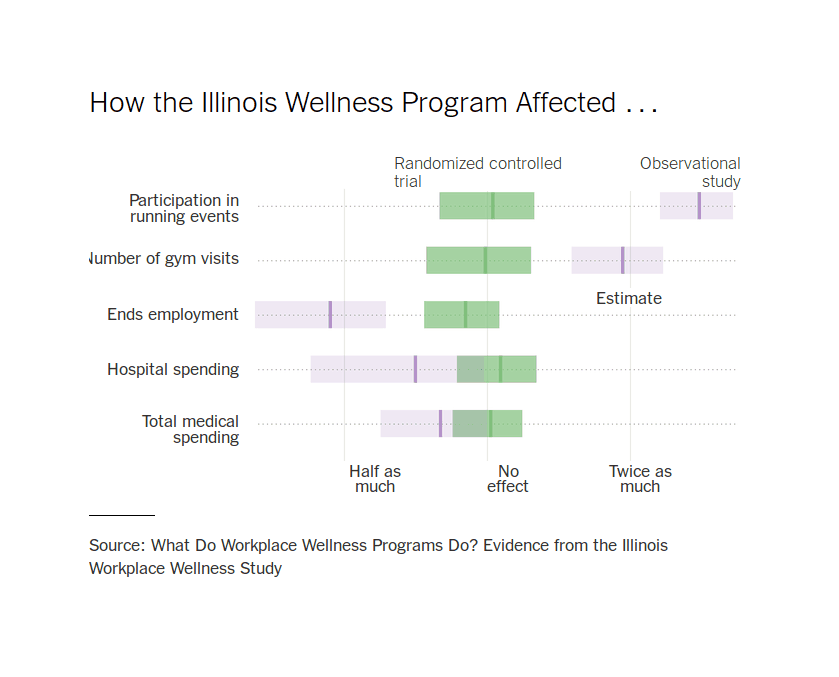

But the most amazing detail, in my opinion, is that this study went further:

It explained why prior observational work showed such large benefits for workplace wellness programs.

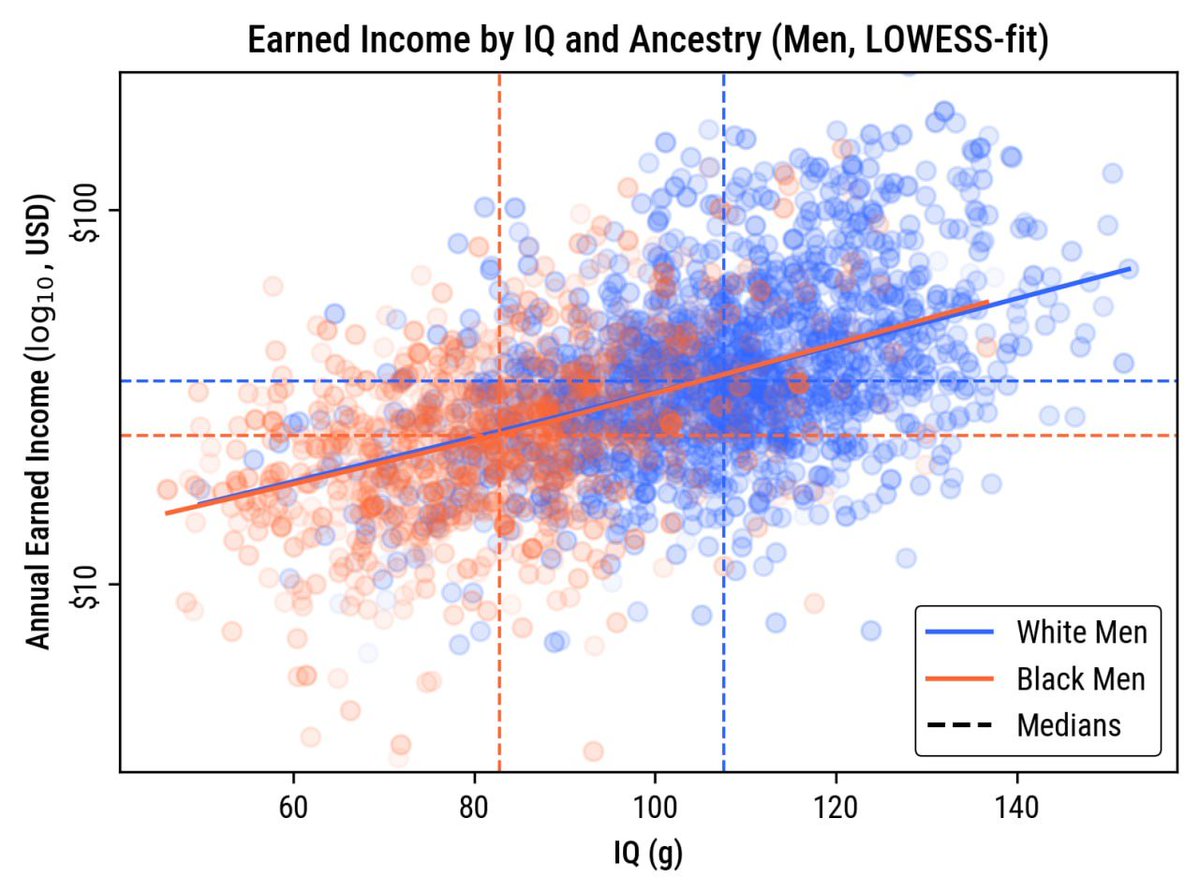

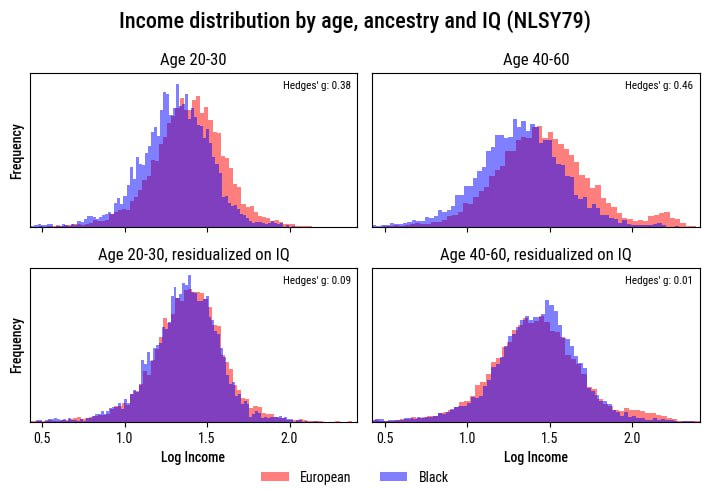

The reason is selection: health-conscious employees selected into the program and stuck with it!

It explained why prior observational work showed such large benefits for workplace wellness programs.

The reason is selection: health-conscious employees selected into the program and stuck with it!

These programs' effectiveness is a classic example of selection leading to results that simply cannot be trusted.

But... how?! Why?! After all, this program had all the ingredients that so many prominent people think will solve America's public health issues.

But... how?! Why?! After all, this program had all the ingredients that so many prominent people think will solve America's public health issues.

The answer is that they misunderstand people.

Most people are lazy, commitment is hard

My recommendation to ppl who haven't learned that is to do a clinical rotation or read abt the thousands of programs across America that have done food delivery coaching, etc., with no effect

Most people are lazy, commitment is hard

My recommendation to ppl who haven't learned that is to do a clinical rotation or read abt the thousands of programs across America that have done food delivery coaching, etc., with no effect

This leads me to something important:

Do you know why Ozempic works so well and has enjoyed such incredible popularity of late?

If you can understand these headlines, you'll get it.

Do you know why Ozempic works so well and has enjoyed such incredible popularity of late?

If you can understand these headlines, you'll get it.

Ozempic makes it automatic to lose weight.

It takes out the effort, and people have an easier time doing more (in this case, work) than they do being asked to eat less or doing things that simultaneously bore and fatigue them (exercise) without a commitment mechanism like a boss

It takes out the effort, and people have an easier time doing more (in this case, work) than they do being asked to eat less or doing things that simultaneously bore and fatigue them (exercise) without a commitment mechanism like a boss

For this reason, GLP-1RAs are going to decisively beat all efforts to advise people, to provide them with healthy food and instructions on how to prepare it, and all of that tried-and-true advice that's been around and in vogue for decades, but clearly hasn't worked.

To top this all off, here's the result of a contemporaneous large, cluster-randomized controlled trial of workplace wellness programs at BJ's Wholesale Club.

Similar intervention, somewhat optimistic effects, and, once again, no results to show for it.

Similar intervention, somewhat optimistic effects, and, once again, no results to show for it.

Sources:

gwern.net/doc/sociology/…

nber.org/sites/default/…

gwern.net/doc/statistics…

businessinsider.com/semaglutide-gl…

nypost.com/2025/01/22/lif…

wsj.com/health/healthc…

gwern.net/doc/statistics…

gwern.net/doc/sociology/…

nber.org/sites/default/…

gwern.net/doc/statistics…

businessinsider.com/semaglutide-gl…

nypost.com/2025/01/22/lif…

wsj.com/health/healthc…

gwern.net/doc/statistics…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh