This 600-year-old altarpiece might be the most complex and deeply symbolic artwork in history.

It will change what you think a painting is capable of doing — because this isn't detail for detail's sake.

Step *inside* it and you'll see why... (thread) 🧵

It will change what you think a painting is capable of doing — because this isn't detail for detail's sake.

Step *inside* it and you'll see why... (thread) 🧵

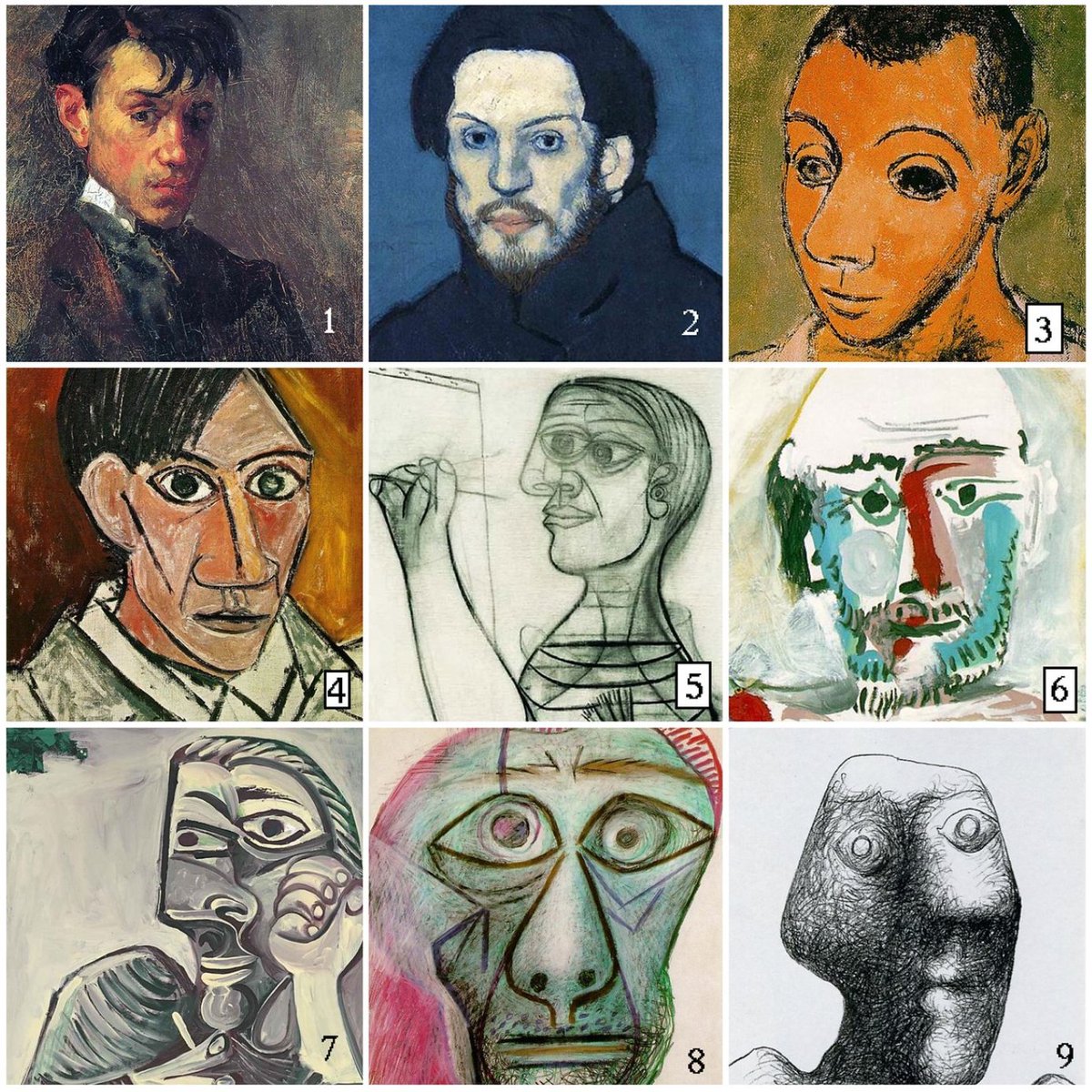

Jan van Eyck's (and his brother Hubert's) Ghent Altarpiece was centuries ahead of its time in 1432.

When closed, it depicts the Annunciation in intentionally muted colors, anticipating what's to come...

When closed, it depicts the Annunciation in intentionally muted colors, anticipating what's to come...

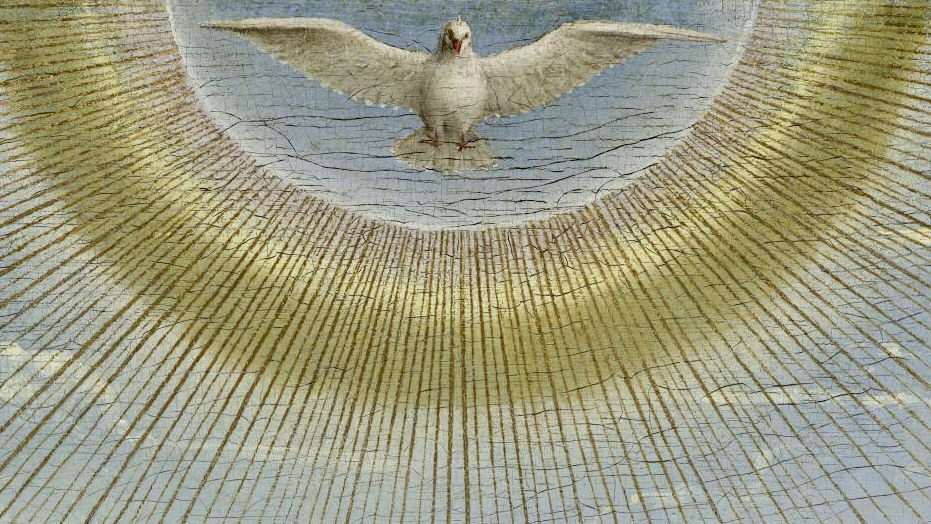

Open it up, and color and light explode at you — out of the darkness comes revelation.

Everything that the Fall, prophets, and Annunciation led up to is revealed in the coming of Christ.

Everything that the Fall, prophets, and Annunciation led up to is revealed in the coming of Christ.

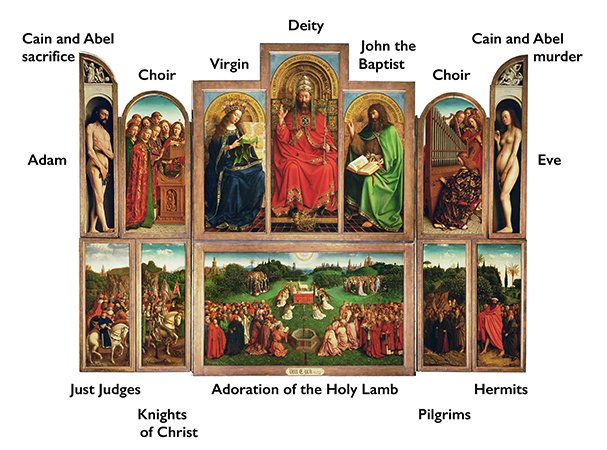

There's too much detail for one thread, but you have God flanked by Mary, John the Baptist, Adam, and Eve.

Standing on an altar below is the Holy Lamb, the symbolic description of Jesus in John's Gospel.

Standing on an altar below is the Holy Lamb, the symbolic description of Jesus in John's Gospel.

God sits on a central throne, crowned in jewels and light.

Note: nobody is sure if it's Christ or God the Father, but ambiguity is the point — Van Eyck was expressing the mystery of the Incarnation.

Note: nobody is sure if it's Christ or God the Father, but ambiguity is the point — Van Eyck was expressing the mystery of the Incarnation.

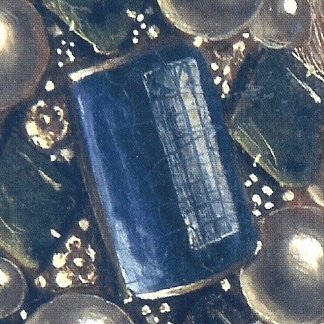

But this painting comes alive not through narrative, but in each and every microscopic detail.

They're not just there to show off — every single ornament, color, fabric, and plant is a conscious symbolic choice...

They're not just there to show off — every single ornament, color, fabric, and plant is a conscious symbolic choice...

Notice the pelican by God's right hand. She feeds her young with blood by piercing her own chest: a symbol of Christ's sacrifice.

For a sense of scale, those chicks are not even 1 cm tall.

For a sense of scale, those chicks are not even 1 cm tall.

Symbols are everywhere. Mary is crowned in lilies marking her purity, columbines her humility, and roses her love.

In fact, there are ~75 plant species present, none chosen at random — the clovers all have 3 leaves to reflect the Holy Trinity.

In fact, there are ~75 plant species present, none chosen at random — the clovers all have 3 leaves to reflect the Holy Trinity.

John the Baptist has a Bible open, and you can count every letter.

Van Eyck makes sure we know which passage he's on: "Consolamini" is the visible first word of Isaiah 40:1, an Old Testament prophecy fulfilled by John.

Van Eyck makes sure we know which passage he's on: "Consolamini" is the visible first word of Isaiah 40:1, an Old Testament prophecy fulfilled by John.

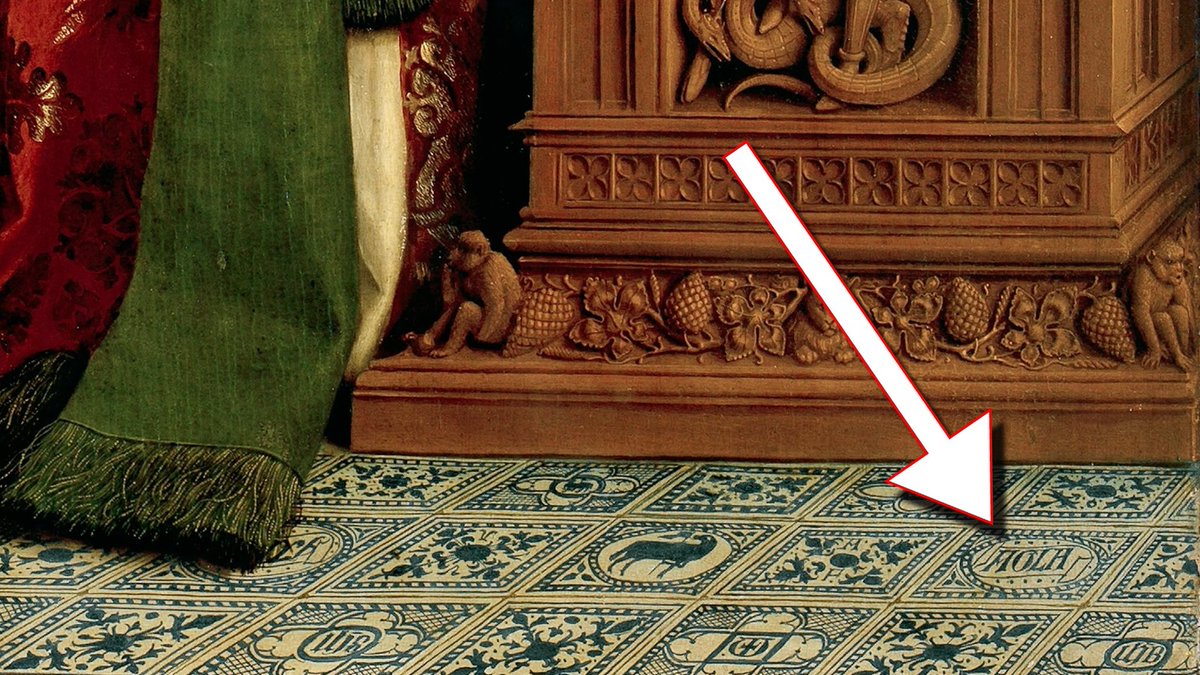

It goes right down to the floor tiles.

Each one is decorated with monograms of Christ and Mary. This acronym, "AGLA", denotes "Atha Gibor Leolam Adonai" ("Thou art mighty forever, О Lord").

Each one is decorated with monograms of Christ and Mary. This acronym, "AGLA", denotes "Atha Gibor Leolam Adonai" ("Thou art mighty forever, О Lord").

It's more mind-blowing when you realize *when* this was painted: the early 15th century.

This was a huge leap in realism from Gothic art only decades before, and the Ghent Altarpiece was the first truly monumental oil painting.

This was a huge leap in realism from Gothic art only decades before, and the Ghent Altarpiece was the first truly monumental oil painting.

But notice the other symbolic detail woven through all this — light.

God's robe shimmers with it, while Adam and Eve dwell in darkness, for they're yet to experience the light of Heaven.

God's robe shimmers with it, while Adam and Eve dwell in darkness, for they're yet to experience the light of Heaven.

But Van Eyck goes well beyond clever symbols. Look now at the heavenly choir.

You can tell from their mouths and expressions that each is singing a different part: soprano, tenor, bass. But zoom in closer...

You can tell from their mouths and expressions that each is singing a different part: soprano, tenor, bass. But zoom in closer...

A jewel worn by one of the angels contains a reflection, made by just a few tiny brush strokes.

A reflection of what?

A reflection of what?

It's the exact window this altarpiece was made to live next to, in Saint Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent.

Van Eyck even painted fake shadows around the FRAMES of the altarpiece to capture the light's direction.

Van Eyck even painted fake shadows around the FRAMES of the altarpiece to capture the light's direction.

There's an important idea in medieval Christianity and in all Van Eyck's paintings: that light itself is divine.

Gothic wonders like Saint Bavo's were designed specifically to maximize it inside...

Gothic wonders like Saint Bavo's were designed specifically to maximize it inside...

But why go to such lengths to render earthly reality in all this detail?

To pull you into the heavenly reality. Van Eyck makes it so tangible you could reach out and touch it.

To pull you into the heavenly reality. Van Eyck makes it so tangible you could reach out and touch it.

And the closer you inspect life, the more you find traces of God inside it.

Just as light permeates and reflects in every inch of this painting, God himself is woven into the very fabric of being...

Just as light permeates and reflects in every inch of this painting, God himself is woven into the very fabric of being...

We go even deeper on legendary art in our free newsletter — do NOT miss the next email.

140,000+ people read it: culture, art and history 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

140,000+ people read it: culture, art and history 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh