In 2014, Steve Bence served as Nike's Program Director in Footwear Sourcing and Manufacturing. He pulled back the curtain on manufacturing in an interview with Portland Business Journal. He said that, if a sneaker retails for $100, it generally costs them about $25 to manufacture

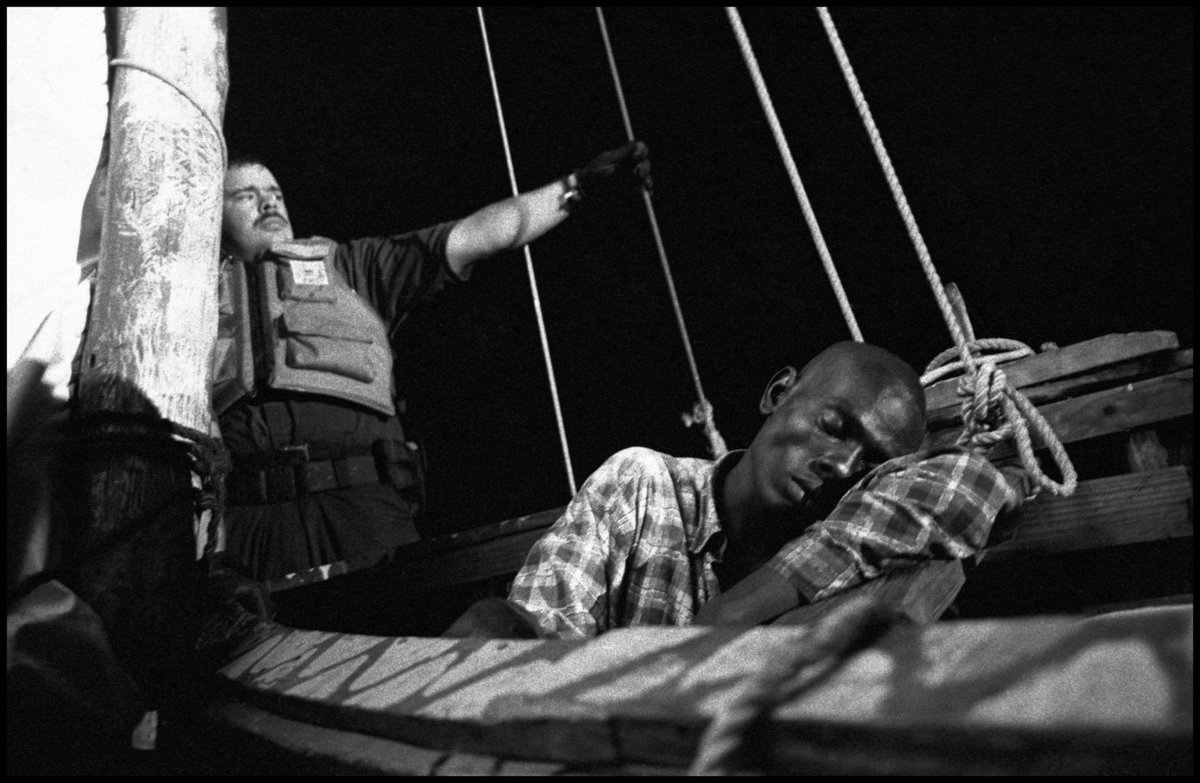

This is the FOB cost. In the industry, "free on board" is the shoe's cost at the point when it's loaded onto a vessel at the port of origin. "Free" refers to how the factory will pay to deliver a finished product up to the point when it boards a ship—the rest is your problem.

Tariffs are calculated on the declared value of the import. In this imaginary case, if Nike paid a factory $25 to produce a pair of sneakers, then their tariff cost is $26. This roughly doubles the cost of making a pair of shoes in Asia and bringing it into the US (landed cost).

"OK," you say, "so that leaves them with a $49 profit. $100 retail minus $25 manufacturing cost and $26 tariff. That's still good."

Not so! There are other costs associated with getting that shoe into your closet. You are not collecting that sneaker at the port.

Not so! There are other costs associated with getting that shoe into your closet. You are not collecting that sneaker at the port.

In 2016, Sole Review took a look at Nike's income statement and came up with this breakdown. On an imaginary $100 shoe, they estimate manufacturing cost is $22. Add freight, insurance, and import taxes, they estimate it costs Nike $27 to bring that shoe from Asia to the US.

They also looked at Footlocker's income statement/ 10k filing and came up with this model. On the same imaginary $100 shoe, Footlocker makes $6 after expenses.

Of course, Nike can retail the shoes themselves, but then they'll also take on similar business costs.

Of course, Nike can retail the shoes themselves, but then they'll also take on similar business costs.

The actual costs associated with shoes will vary depending on the design, sourcing, and other specifics. The imaginary shoe above is set at $100 to make things easier as a percentage. For completeness, you can read Sole Review's story here:

solereview.com/what-does-it-c…

solereview.com/what-does-it-c…

From this model, you can see a few things.

First, adding $26 tariff at the port doesn't just add $26 to the final price. Everything here works off of percentages. In this simple model, we say Nike has a landed cost of $25, sells it to Footlocker for $50, and they retail at $100

First, adding $26 tariff at the port doesn't just add $26 to the final price. Everything here works off of percentages. In this simple model, we say Nike has a landed cost of $25, sells it to Footlocker for $50, and they retail at $100

But if we bump the cost of freight, insurance, and customs from $5 to, say, $28, then they wholesale the shoes to Footlocker for about $75. And if Footlocker purchases Nike shoes for $75, then they retail them for $150. Everyone needs to fixed percentages to avoid losses.

The second thing we see is that Asian manufacturing in Asia produces US jobs. You go to Footlocker to buy a pair of $100 shoes because you can afford them. This creates jobs for the Footlocker employees, Nike designers, marketing teams, and other US people throughout this chain.

The third thing we see is that Nike only paid the factory about $25 to make these sneakers. How much did it cost the factory to produce them? I don't have numbers on that, but if we assume the usual turnkey model, then maybe $12.5? And how much of that went to the worker?

Again, it's a popular misconception that all overseas production is sweatshops. Production can be done ethically abroad and still be relatively cheap because the cost of living is not the same everywhere. I encourage you to note assume that every Asian worker is a slave.

We have some idea of how much it would cost to make sneakers in the US. Victory/ Hersey (before they closed), SAS, and certain New Balances are made here. They retail for about $220.

Note, many of these rely on imported materials (up to 30%). So they will go up with tariffs.

Note, many of these rely on imported materials (up to 30%). So they will go up with tariffs.

I think making shoes is a perfectly fine job, although it suffers from the same problem as other manufacturing jobs. As the US has switched to a post-industrial economy, a lot of the wage growth has been in knowledge intensive services—medicine, law, engineering.

That means the Nike designer and marketer typically see more wage growth year-after-year than someone working on the manufacturing line (especially if they're not unionized and can leverage collective bargaining power).

Tech optimists think that technology will make factory jobs easier and better for workers. I'm less sanguine. I think some tech improves productivity and wages; other types of tech deskills and eliminates jobs (look at AI with illustration art).

https://x.com/dieworkwear/status/1908736017886277789

I raise this only because I see some people suggest that it only costs Nike $2 to make a pair of sneakers in Asian sweatshops, which retail on the shelf for $150, and this is $148 profit. And if we move this back to the US, American workers can capture some of that money.

I think the truth is much more complicated. Manufacturing overseas can create certain jobs here by offering a more affordable product. In the end, you may actually see a *loss* of US jobs as fewer people pay for $220 sneakers, both at home and abroad.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh