Last month there was an announcement that I thought was a major advancement in world health, but it got little attention.

I thought I would tell you all a little bit about it and why it is so important.

1/25

I thought I would tell you all a little bit about it and why it is so important.

1/25

This breakthrough has to do with HIV, which was a zoonotic pathogen. The progenitor of HIV infects chimpanzees in Cameroon.

No one knows exactly when or how HIV crossed into humans, but the first undisputed HIV patient sample (discovered retrospectively) was from 1959 in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

No one knows exactly when or how HIV crossed into humans, but the first undisputed HIV patient sample (discovered retrospectively) was from 1959 in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

HIV smoldered for decades before becoming widespread in the early 80s.

At the time, being diagnosed with an HIV infection was a death sentence.

There was no real cure (still isn’t) and no treatment. By any measure, HIV was one of the worst diseases of the last century.

3/

nature.com/articles/d4158…

At the time, being diagnosed with an HIV infection was a death sentence.

There was no real cure (still isn’t) and no treatment. By any measure, HIV was one of the worst diseases of the last century.

3/

nature.com/articles/d4158…

Throughout the 80 and 90s many antivirals were developed, but they all were doomed to fail. HIV mutated so fast that it quickly developed resistance to every drug we threw at it.

4/

4/

The breakthrough came in 1996 when HIV researchers such as David Ho found that they could treat HIV if patients received a cocktail of antivirals all at once.

HIV went from being a death sentence, to being a life-long treatable disease.

5/

HIV went from being a death sentence, to being a life-long treatable disease.

5/

BTW, David Ho still maintains a very active research lab at Columbia University, which apparently now has all of its NIH grants frozen.

Let no good deed go unpunished.

6/

science.org/content/articl…

Let no good deed go unpunished.

6/

science.org/content/articl…

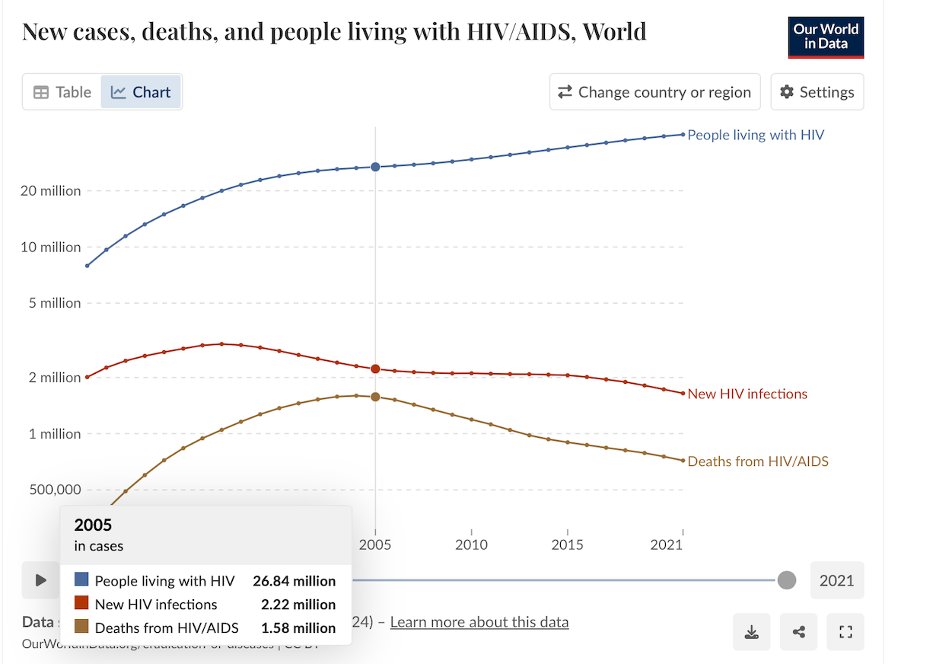

Although HIV became treatable in 1996, the world death rate from HIV didn’t start to go down until almost a decade later. Why then?

A big part of the reason was the program PEPFAR, which was launched by George W. Bush in 2003. This program focused on getting lifesaving drugs in the hands of people who needed them.

7/

A big part of the reason was the program PEPFAR, which was launched by George W. Bush in 2003. This program focused on getting lifesaving drugs in the hands of people who needed them.

7/

While some of this funding has been restored, the future of PEPFAR remains quite uncertain.

9/thinkglobalhealth.org/article/pepfar…

9/thinkglobalhealth.org/article/pepfar…

Plus, a lot of NIH grants studying HIV that had foreign collaborators are also being terminated.

10/science.org/content/articl…

10/science.org/content/articl…

Anyway, back to the breakthrough stuff.

For the last few decades, HIV drugs have continued to improve. Patients now take fewer drugs, less often, and with fewer side effects.

11/ fight.org/hiv-medication…

For the last few decades, HIV drugs have continued to improve. Patients now take fewer drugs, less often, and with fewer side effects.

11/ fight.org/hiv-medication…

However, HIV hasn’t gone away.

People still get infected, and they then require treatment for the rest of their lives.

There are more people living with HIV today than ever before (over 40 million), and the number keeps going up.

12/

People still get infected, and they then require treatment for the rest of their lives.

There are more people living with HIV today than ever before (over 40 million), and the number keeps going up.

12/

Once people are undergoing treatment, they are unlikely to pass on the virus.

The problem is the spread that occurs before people know they are infected.

What we really need is a fool-proof way of preventing people at high risk from becoming infected in the first place.

13/

The problem is the spread that occurs before people know they are infected.

What we really need is a fool-proof way of preventing people at high risk from becoming infected in the first place.

13/

About 15 years ago groups started working on what is called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) where people at high risk can take HIV antivirals that could prevent them from being infected in the first place.

14/

14/

However, PrEP was expensive, and not always practical.

What we really needed is a vaccine (we’re not even close), or an effective, long-lasting prophylactic.

15/

What we really needed is a vaccine (we’re not even close), or an effective, long-lasting prophylactic.

15/

Until very recently, almost all of the drugs that blocked HIV targeted one of its enzymatic proteins: RT, IN, or PR.

However, for decades numerous HIV researchers (myself included) studied the process of HIV assembly (CA protein) with the idea that it would be a better target for blocking the virus.

16/

However, for decades numerous HIV researchers (myself included) studied the process of HIV assembly (CA protein) with the idea that it would be a better target for blocking the virus.

16/

This dream recently became a reality with the development of the drug lenacapavir, a capsid inhibitor where a single dose could last as long as 6 months.

17/

science.org/content/articl…

17/

science.org/content/articl…

However, the news got even better last month when it was announced that lencapavir could be used for PrEP with as little as one treatment per year.

That is a treatment that could actually work!

18/

aidsmap.com/bulletin/confe…

That is a treatment that could actually work!

18/

aidsmap.com/bulletin/confe…

That’s the good news.

Please indulge me for a moment to get on my soap box to tell you why we should really care about continuing to fight the war on HIV, even though not that many people are dying of HIV in the US.

19/

Please indulge me for a moment to get on my soap box to tell you why we should really care about continuing to fight the war on HIV, even though not that many people are dying of HIV in the US.

19/

The first is simply the forest fire analogy. Forest fires, like pathogens, don’t respect national borders.

HIV started in Africa, but it didn't stay there.

If you live in a forest, it really makes sense to fight the fire before it’s on your property.

20/

HIV started in Africa, but it didn't stay there.

If you live in a forest, it really makes sense to fight the fire before it’s on your property.

20/

But there is a reason that is even more important. Patients with untreated HIV become severely immune suppressed, and immune suppressed patients are breeding grounds for new pathogens and variants.

21/

21/

Using COVID as an example, in early 2021 we had a vaccine, cases were dropping, and it seemed like the pandemic was almost over.

Then began a series of new waves which were each driven by a new COVID variant.

22/

Then began a series of new waves which were each driven by a new COVID variant.

22/

These variants were not the result of gradual changes acquired by circulating lineages.

They were each, wildly different variants.

We are all but certain these new variants were all derived from individuals (presumably immune compromised) with long persistent infections.

23/

They were each, wildly different variants.

We are all but certain these new variants were all derived from individuals (presumably immune compromised) with long persistent infections.

23/

Persistent infections are training grounds for pathogens.

People worry about ‘gain of function’ work, but failing to continue treating the 40+ million people in the world living with HIV would be the largest and most dangerous gain of function ‘experiment’ in history.

24/

People worry about ‘gain of function’ work, but failing to continue treating the 40+ million people in the world living with HIV would be the largest and most dangerous gain of function ‘experiment’ in history.

24/

I’ll get off my soapbox now. Thanks for reading.

25/25

25/25

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh