Today, @realDonaldTrump (@WhiteHouse) signed an executive order on drug pricing. Thank you to everyone who pointed out that @shoshievass, Pierre Dubois, and I looked at this sort of policy in our paper. A quick thread on the main results with some important nuance.

https://twitter.com/nberpubs/status/1528012747379576834

Drug price controls have substantial support on both sides of the aisle for a reason. The US is essentially the only developed country that doesn't regulate drug prices, and as a result we pay many times what other countries do.

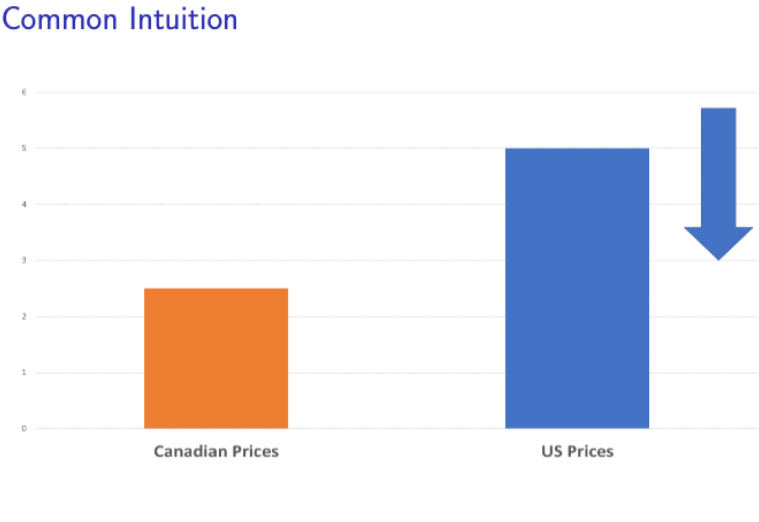

Trump proposes to implement a "most-favored-nation" requirement (i.e. "reference pricing"). Such a rule might, for example, dictate that drug companies can't sell at higher prices in the US than in Canada. Common intuition is that US prices would drop to Canaian price level.

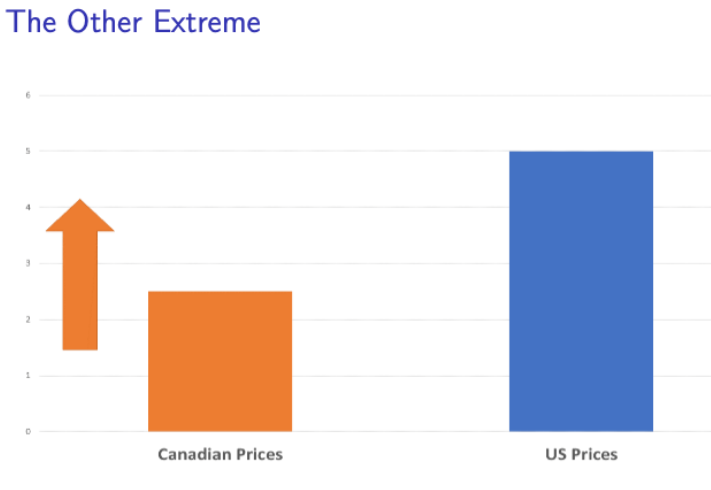

While that might work very briefly, drug companies will realize the price they set in Canada constrains the price they can set in the US. A smart drug company might insist on a much higher price in Canada to avoid having to lower their price in the US!

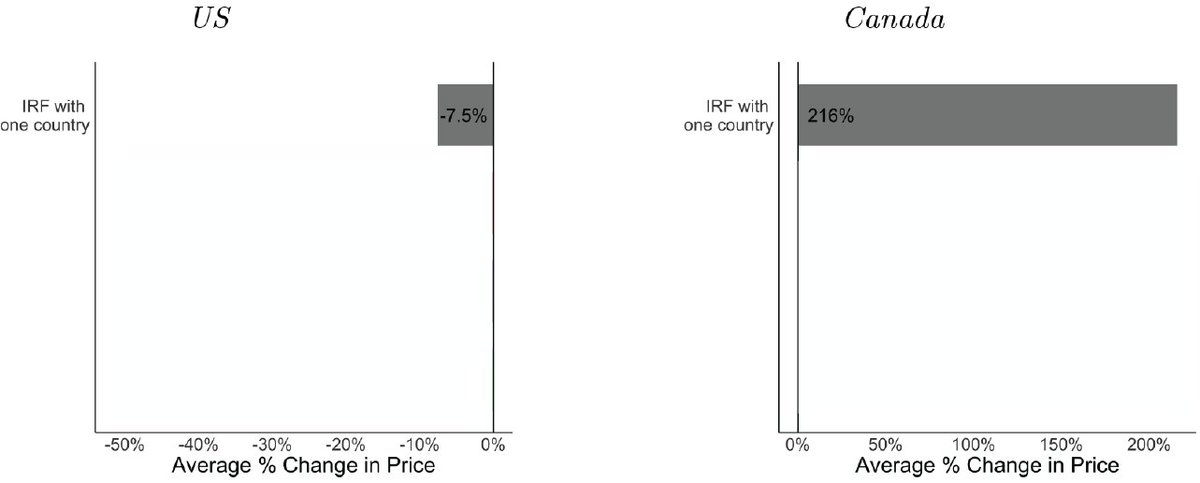

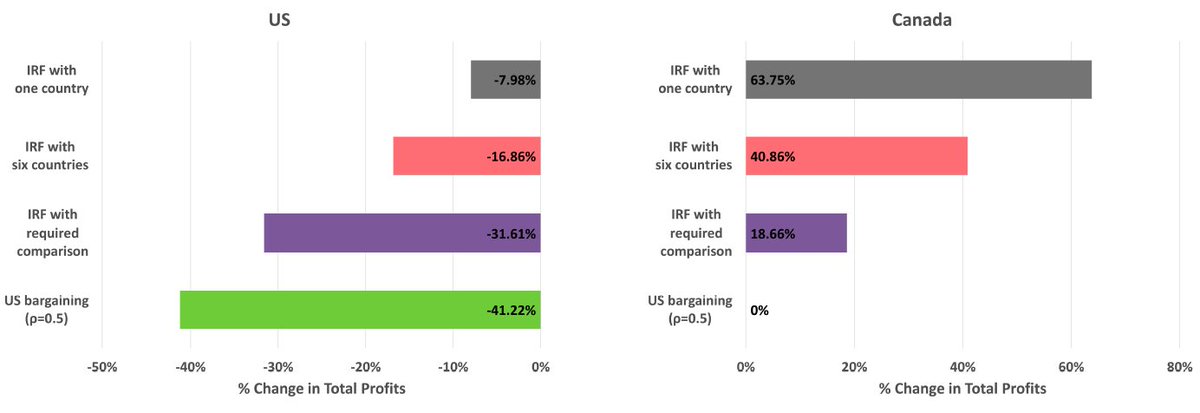

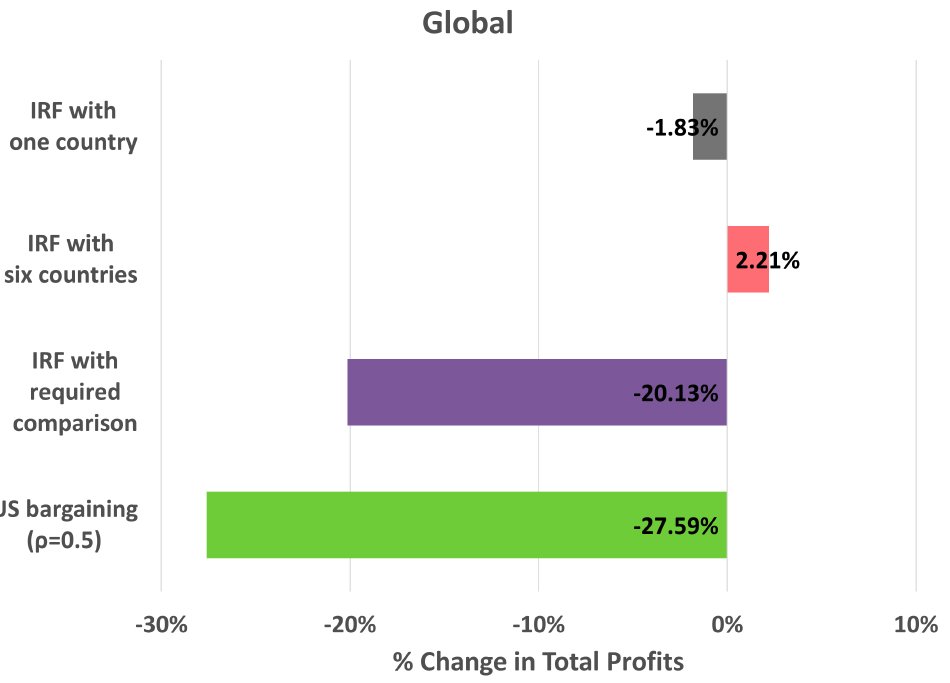

And, indeed, that's the case. We estimate a model of pharmaceutical supply and demand in the US and Canada and find that such a reference pricing rule would lower US drug prices by 7.5% while raising Canadian prices by 216%!

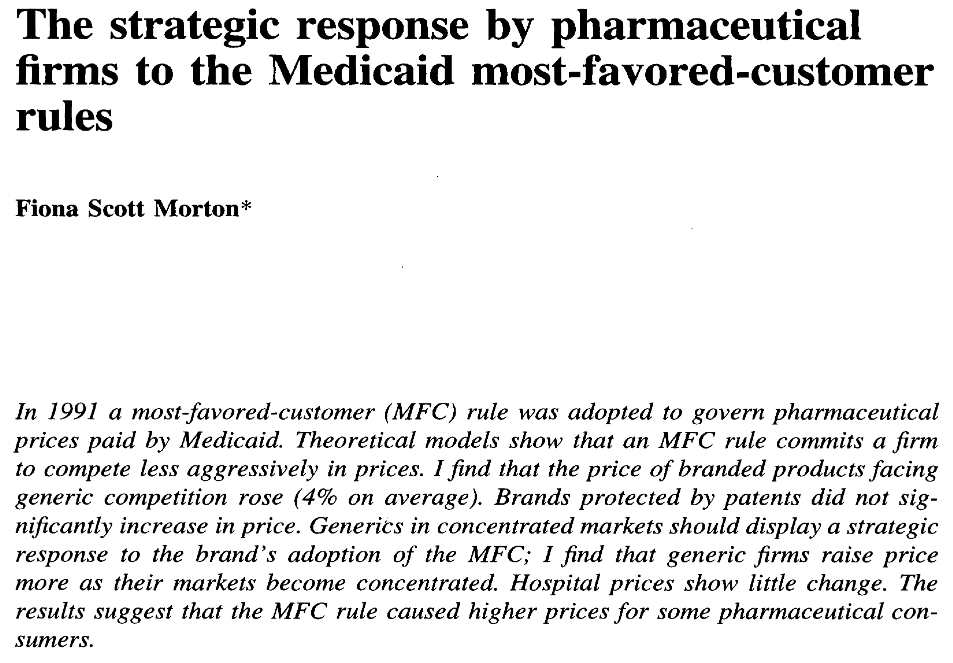

You might be skeptical that drug companies would be so strategic. But there's great evidence from Fiona Scott Morton that drug companies were strategic in exactly this way when Medicaid implemented a reference pricing rule within the US.

jstor.org/stable/2555805…

jstor.org/stable/2555805…

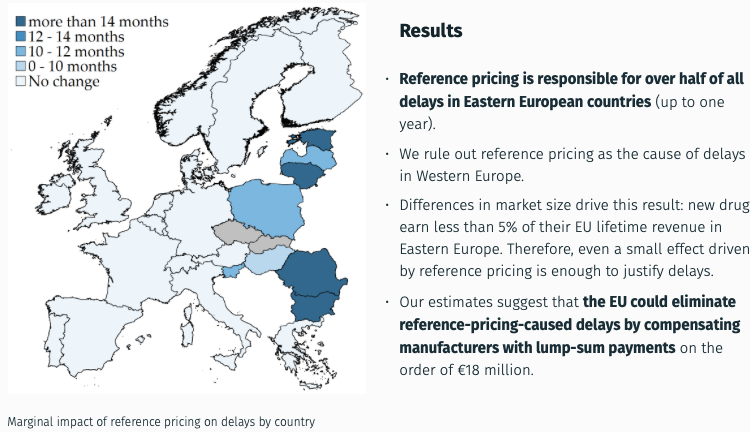

Why can't the Canadian government keep negotiating low prices? Put simply, under reference pricing, drug companies would rather leave Canada than lower their US prices too much. Luca Maini has an incredible paper examining this phenomenon in Europe: aeaweb.org/articles?id=10…

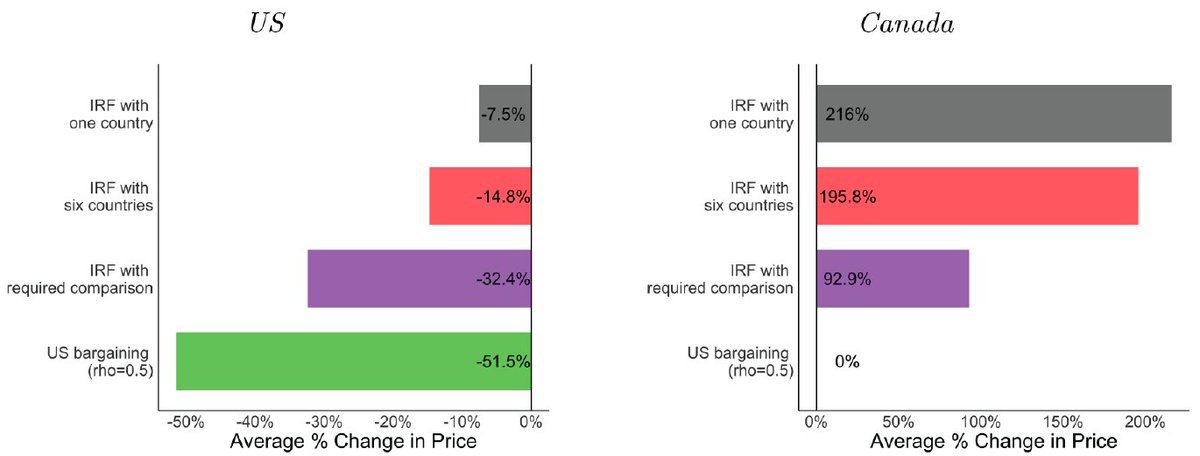

To be fair, proposals often reference many or larger countries. These are more effective in lowering prices (e.g., ~15% price reduction for referencing 6 countries like Canada). But the primary effect is *still* to raise prices dramatically in the referenced countries.

Note that in these examples, drug companies are able to raise their prices abroad by threatening to leave. What if the US neutralized that threat by requiring drug companies to sell in reference countries? Prices decrease much more in the US and increase by *merely* 93% abroad.

Of course, lowering prices in the US doesn't mean we need to raise prices abroad. We could simply negotiate prices in the US without referencing other countries.

What does reference pricing mean for drug companies? They earn less profit in the US and more profit abroad.

In fact, in some cases, profits abroad increase by enough to more than offset lost profits in the US! This may explain why pharmaceutical stock prices didn't tank today with the announcement.

What should we take away from all of this? A few things:

1. While reference pricing would lower drug prices in the US, most plausible implementations would lead to only small price reductions. The principal effect would be to raise prices abroad.

1. While reference pricing would lower drug prices in the US, most plausible implementations would lead to only small price reductions. The principal effect would be to raise prices abroad.

If raising prices abroad is your primary goal, then reference pricing is perhaps a very reasonable approach. I'm sympathetic to this argument. Other developed countries undoubtedly free ride on the US paying high prices that incentivize pharmaceutical innovations.

An important caveat here is that it's undoubtedly stupid to reference developing countries. Chaudhuri, @PennyG_Yale, and @panlejia have a great paper demonstrating that the costs far outweigh the benefits to generating profits in developing countries:

pages.stern.nyu.edu/~acollard/AIDS…

pages.stern.nyu.edu/~acollard/AIDS…

2. The devil is in the details. Something as small as the rules when a drug company chooses not to launch in a reference country makes a huge difference in how effective reference pricing is. We really need much more information to estimate the efficacy of the new policy.

3. If you want to lower prices in the US without raising prices abroad, you can do that directly. There's no need to implement reference pricing. However, doing so in this way isn't free. It could seriously reduce incentives for new pharmaceutical innovations, which would be bad!

Thanks for reading! You can check out the full paper here:

nber.org/papers/w30053

nber.org/papers/w30053

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh