Among the most visible reminders of Rome's storied hegemony are its aqueducts.

These engineering marvels channeled the lifeblood of civilization for near a millennium.

Here’s how they worked🧵 (thread)

These engineering marvels channeled the lifeblood of civilization for near a millennium.

Here’s how they worked🧵 (thread)

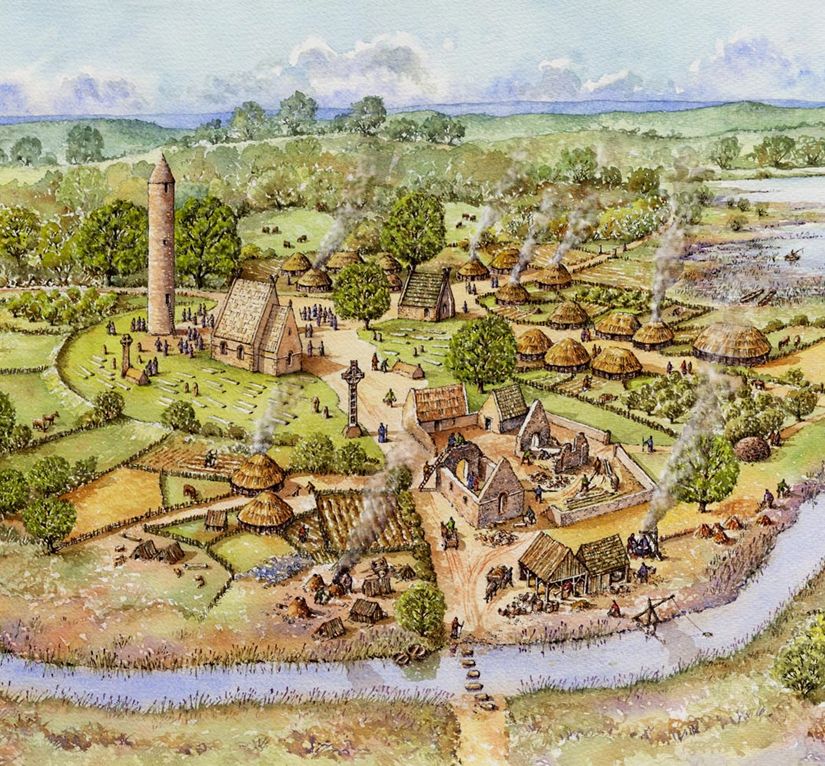

Rome’s aqueducts had humble origins, much like the city itself.

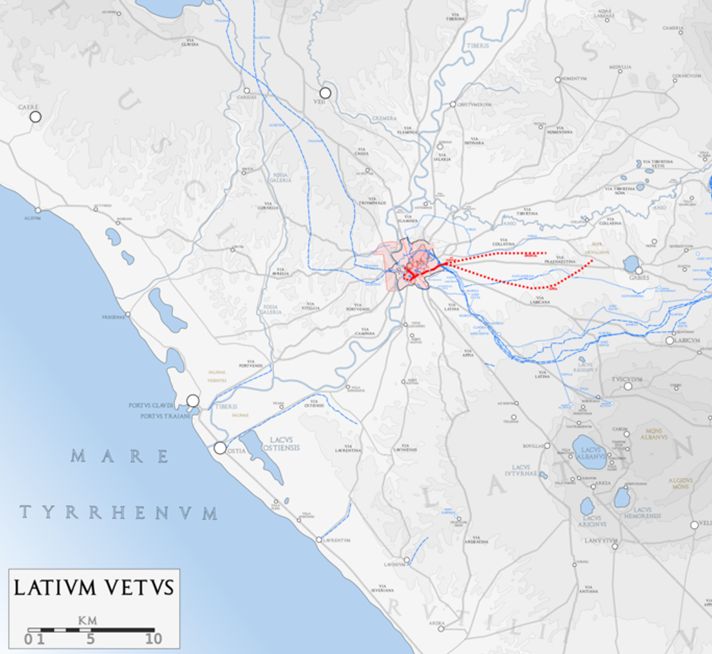

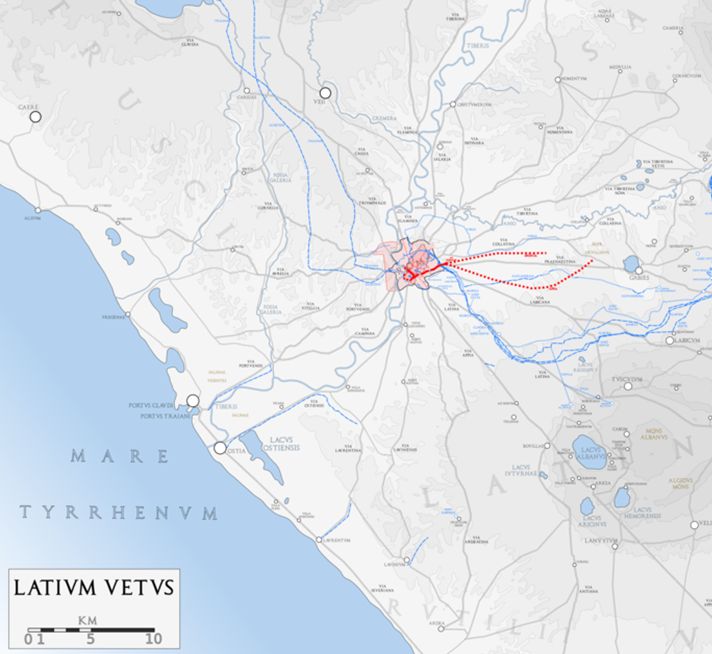

The first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was constructed in 312 BC to supply the city’s cattle market.

The first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was constructed in 312 BC to supply the city’s cattle market.

Its source could be found in a group of springs inhabiting a stretch of local marshland, flowing an impressive 10.2 miles to Rome from the east and emptying into the Forum Boarium.

Though the River Tiber was close by and used initially as the city’s water supply, it became dangerous once population grew—constant human activity near the river polluted it.

Rome was wise to keep their water source at a distance.

Rome was wise to keep their water source at a distance.

As the city’s population grew, more aqueducts were needed.

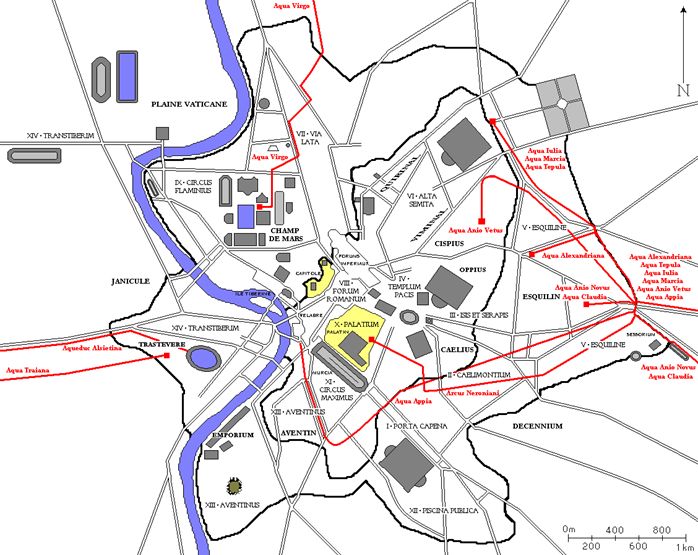

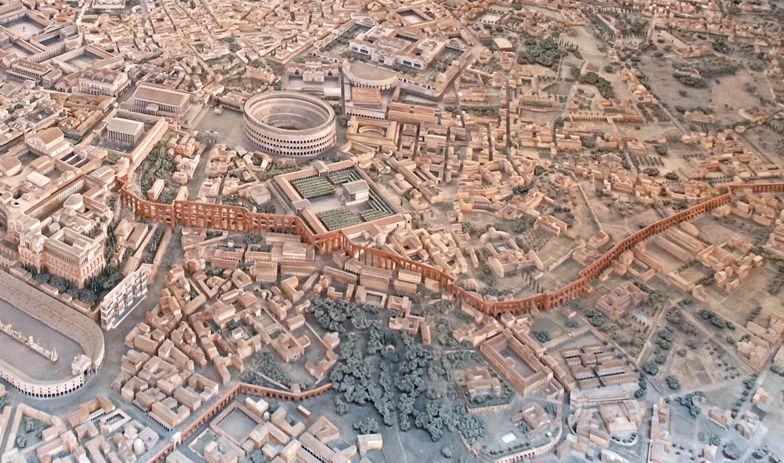

By the 3rd century AD, Rome had over a million inhabitants, and required a whopping eleven aqueducts to feed their economy and public amenities.

By the 3rd century AD, Rome had over a million inhabitants, and required a whopping eleven aqueducts to feed their economy and public amenities.

The four major aqueducts were the Aqua Anio Vetus, the Aqua Marcia, the Aqua Claudia and the Aqua Anio Novus.

The combined length of Rome’s aqueducts is estimated to be around 500 miles (800 km), while approximately 29 miles (47 km) were above ground on masonry supports.

Most people identify aqueducts with these visible sections but the majority ran underground.

Most people identify aqueducts with these visible sections but the majority ran underground.

Estimates of the city's supply, based on ancient calculations by civil engineer Frontinus in the 1st century, range from 160 million gallons to 250 million gallons per day.

This estimate puts the average Roman consuming ~200 gallons of water per day.

This estimate puts the average Roman consuming ~200 gallons of water per day.

So how did Roman aqueducts actually work?

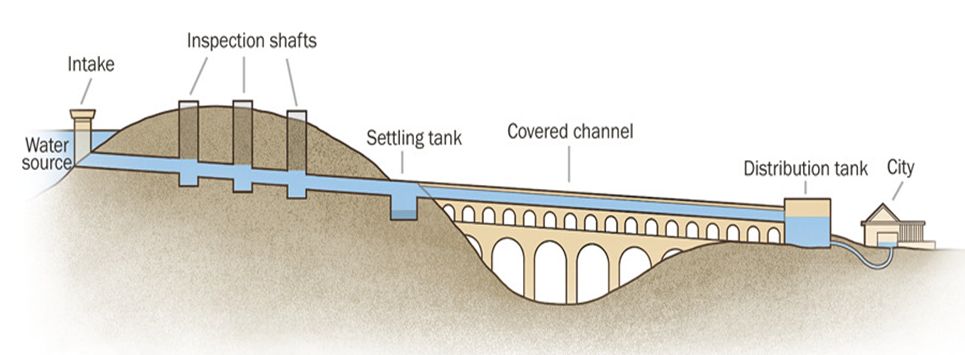

Aqueducts used a readily accessible energy source—gravity—to move water over vast distances.

Aqueducts used a readily accessible energy source—gravity—to move water over vast distances.

They maintained a slight overall downward gradient through channels of stone, concrete, clay, or lead. To increase/decrease water flow, one simply made the gradient steeper/shallower in that section.

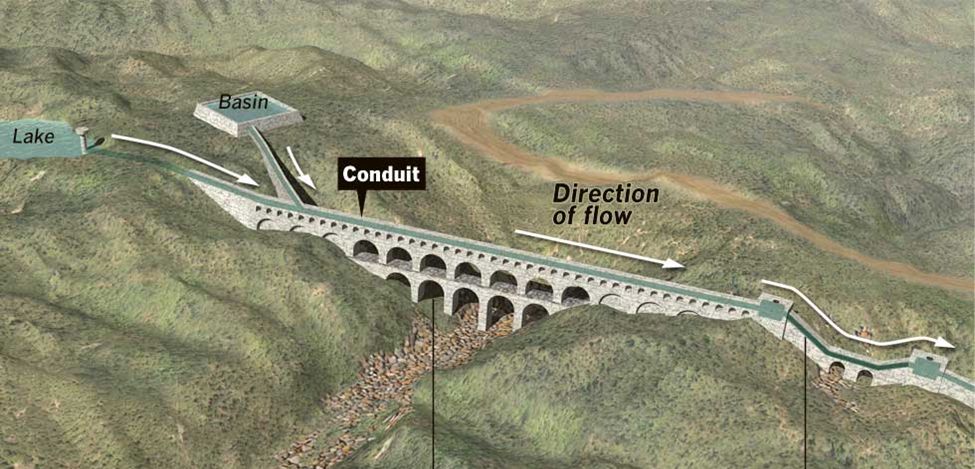

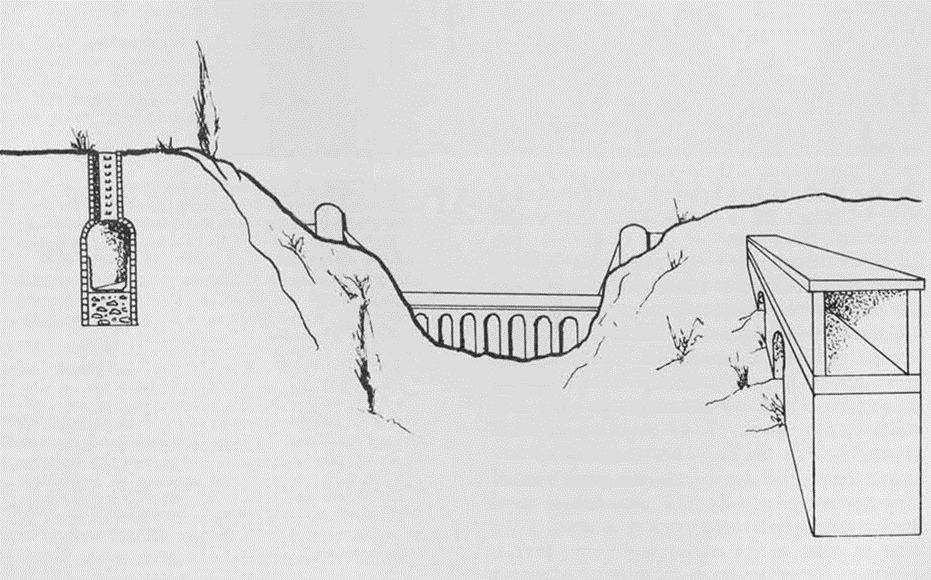

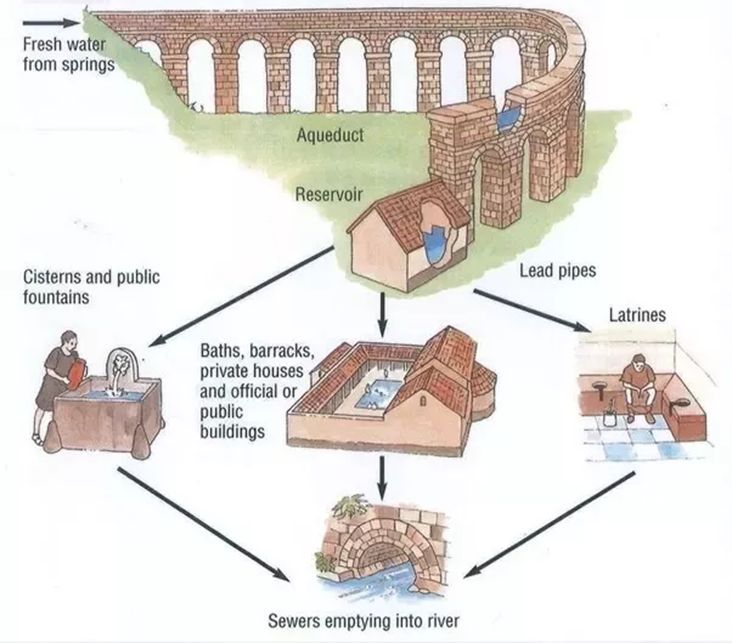

Most aqueduct channels were underground, but where lowlands made this difficult, two methods were employed to cross the gap: bridges and siphons.

Aqueduct bridges were straightforward—they carried the channel of water over the gap via arches, maintaining the downward gradient.

Aqueduct bridges were straightforward—they carried the channel of water over the gap via arches, maintaining the downward gradient.

Siphons were a little more complicated but a clever engineering feat. A siphon was basically a water-slide, allowing the water to drop rapidly before the gap. Once the gap was crossed, it sloped upward again, but now the water had gained enough momentum to go uphill.

Siphons could be expensive and needed lead or ceramic pipes to work well, so arched-bridges were the preferred method.

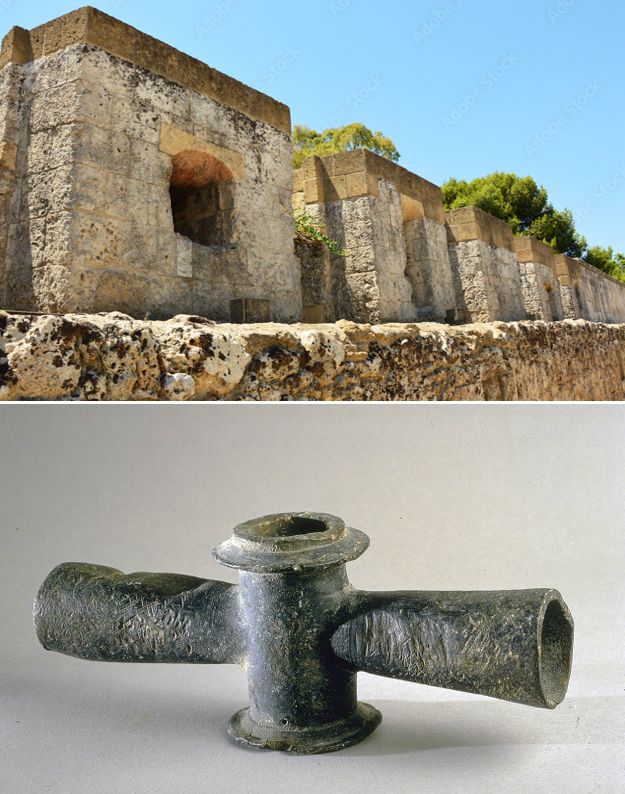

Once the aqueduct neared its destination, sedimentation tanks were implemented to reduce any water-borne debris. Then, the water was held in distribution tanks and regulated by stopcocks (valves) to individual destinations.

Water was used for public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households, as well as for industrial and agricultural operations like mines, mills, and farms.

Water is the lifeblood of any civilization, and it was the aqueducts of Rome that allowed the city to flourish beyond any before it.

It’s often the engineering capabilities of a culture that set it apart from others.

It’s often the engineering capabilities of a culture that set it apart from others.

Historian Dionysius credited Rome’s infrastructure for the city’s dominance:

“The extraordinary greatness of the Roman Empire manifests itself above all in three things: the aqueducts, the paved roads, and the construction of the drains."

“The extraordinary greatness of the Roman Empire manifests itself above all in three things: the aqueducts, the paved roads, and the construction of the drains."

If you enjoyed this thread and would like to go deeper into topics like this, join our Substack community — it’s where we put our most in-depth content👇

thinkingwest.substack.com

thinkingwest.substack.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh