Something remarkable happened in India on May 26. Electricity prices on the power exchange crashed to almost zero. Not cheap - practically free. For several hours between 9 AM and 1 PM, power was trading at just 11 paise per kilowatt-hour.🧵👇

Generators were basically giving away electricity. The price hit rock bottom - less than the exchange's own transaction fee. The culprit? India's solar power boom.

Here's how electricity pricing works in India. Most electricity comes from long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) between generators and distribution companies. These contracts require fixed payments for fixed amounts whether the power is actually needed or not.

But there's also a short-term market - about 15% of total consumption. Within that, the spot market on exchanges like Indian Energy Exchange is just 8%. Here, power plants sell excess power while distribution companies buy extra power to cover shortages.

This spot market works like a regular marketplace. Every day, power generators bid to sell electricity. Bids are accepted in increasing order by cost - cheapest first, moving up until there's enough to meet demand. The final price is set by the most expensive source needed.

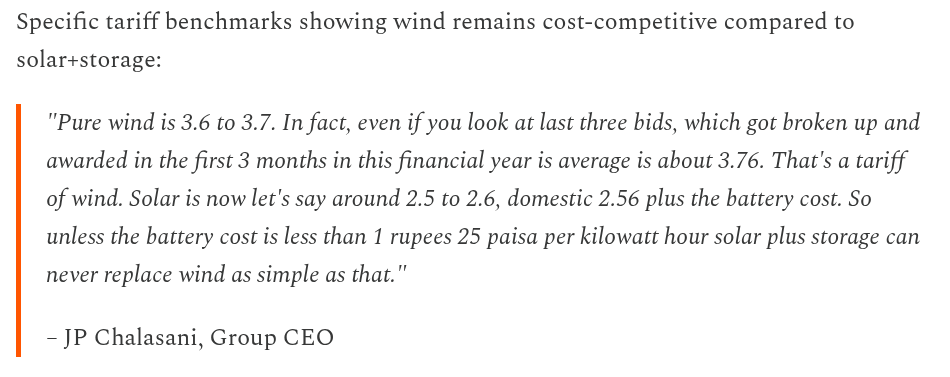

At different times, different power sources dominate. When the sun shines bright and there's lots of solar power, solar plants have an inherent advantage due to lower running costs. And on May 26, there was so much solar that prices nearly touched zero.

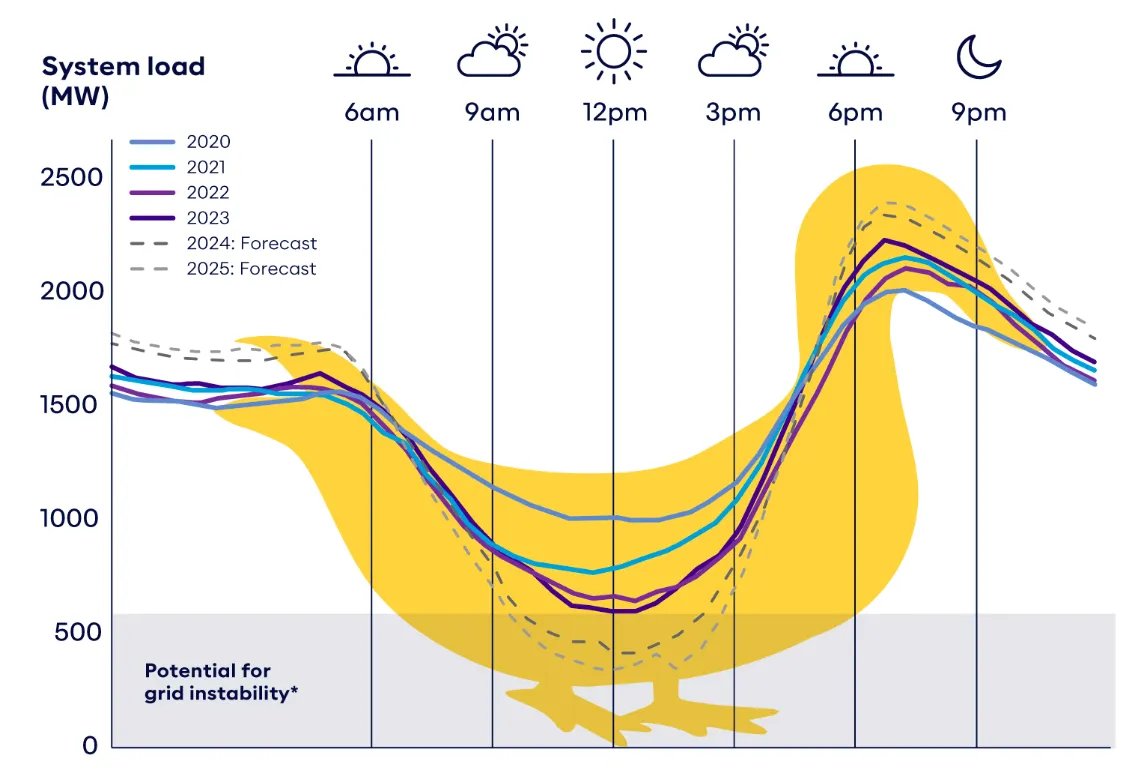

Here's the problem: when the sun blazes at midday, solar panels crank out massive amounts of electricity - enough to power entire states. But people don't need the most electricity when the sun is strongest. They need it in the evening when everyone comes home.

This creates the "duck curve" - a graph that looks like a duck's back. Electricity demand dips during sunny midday hours as solar takes over, then ramps up steeply in the evening when solar fades and lights, ACs, and TVs turn on across the country.

Classic supply-demand mismatch. A massive supply of cheap solar power floods the system right when demand is relatively low. And grid operators can't just turn it off - India has declared solar and wind "must-run" power, meaning it can't be switched off.

So during sunny midday hours, all that solar power keeps flowing whether the grid needs it or not. If conventional plants can't ramp down fast enough, there's suddenly way more electricity than anyone wants to buy. Result? Prices crash.

Sometimes prices don't just drop to zero - they can go negative. Generators actually pay people to take their electricity. Some power plants are so expensive to shut down and restart that they'd rather pay to keep running than face massive stopping costs.

But zero prices are actually a problem. Solar developers who depend on market revenues can't recover investments if power is regularly free. Distribution companies lose money paying solar farms under contract but selling for pennies on the market.

Example: a state distribution company pays a solar farm Rs 2.50 per unit under contract, but sells that same power for Rs 0.10 during surplus hours. The company loses Rs 2.40 on every unit - losses ultimately passed on to consumers through higher tariffs.

Traditional coal and gas plants get squeezed out during midday hours, making it harder to recover costs. States with lots of solar like Rajasthan and Gujarat see their electricity export revenues collapse as daytime power value falls.

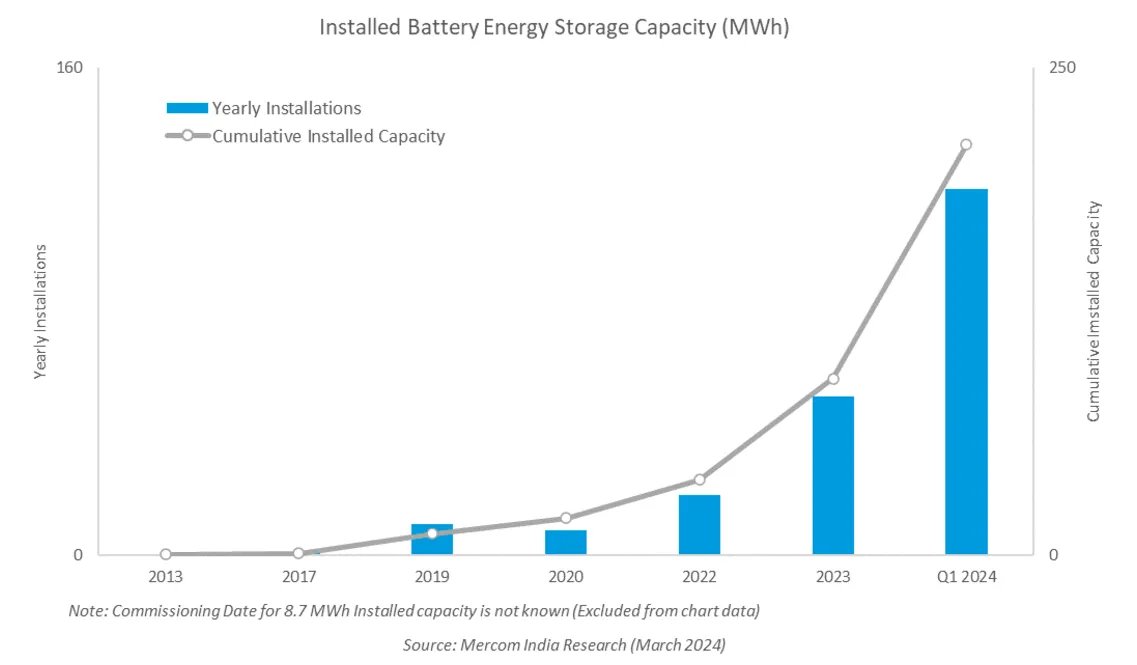

The solution? Capture all that free midday solar power and save it for when people actually need it. That's what batteries do. But here's the problem: India only had about 220 MWh of battery storage as of March 2024. That's nothing compared to thousands of megawatts of daily solar.

The biggest barrier isn't technology - it's economics. Battery systems are still expensive to build, and in India's price-sensitive market, the business case doesn't make sense. This creates a chicken-and-egg problem for developers.

Policymakers are trying alternatives: time-of-day pricing to encourage midday consumption, massive transmission line projects to move surplus power between states, market reforms like capacity payments, and storage incentives. Progress has been slow due to costs and regulations.

This is a global phenomenon. California saw negative prices 13% of all hours in 2024, with generators paying consumers to take electricity. Australia hit 24-26% negative pricing in some states. Germany recorded 475 hours of negative prices in 2024, up from 301 hours the previous year.

India is targeting 500 GW of renewable capacity by 2030, more than doubling what it has today. The irony is perfect - solar power has become so successful that it's creating a new problem: too much cheap, clean electricity. The sun is giving us more energy than we know what to do with. The question is: are we smart enough to figure out how to use it?

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's Daily Brief in detail. You can watch the episode on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts. All links here: thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/inside-india…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh