1. Here’s an overhead view of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

I used this image in my newly published book to prove a point. Then along came a so-called "real archaeologist," trying to make a fool of me. "Real archaeologists" come and go—I don’t even remember his name.

But a few things have happened since then. Let’s see who was right.

Let’s zoom in!

I used this image in my newly published book to prove a point. Then along came a so-called "real archaeologist," trying to make a fool of me. "Real archaeologists" come and go—I don’t even remember his name.

But a few things have happened since then. Let’s see who was right.

Let’s zoom in!

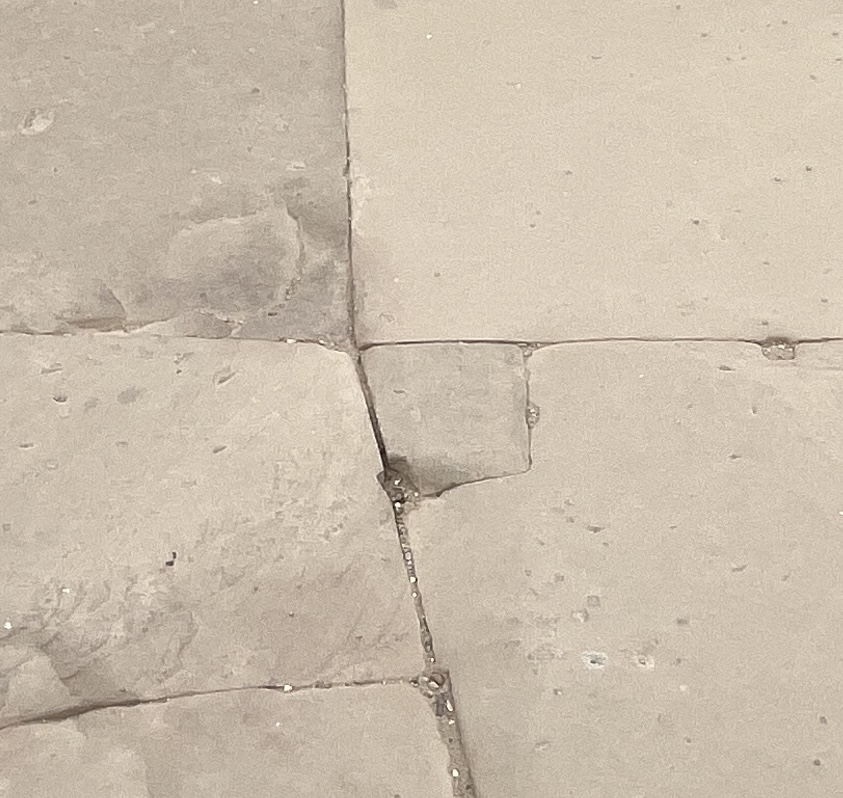

2. In this image, we can spot all kinds of interesting details—from the impressions spanning multiple stones (top right, orange fram) to the skillful use of a square drill (bottom left, green frame).

In my book, I wrote that these are clear signs that these stones are artificial. To which the real archaeologist responded: “So many people have been on top of the pyramid, entire TV crews—it’s obvious they chiseled out those square holes.”

Alright, fine. Let’s say you’re right. (You’re not—we’ll see in a moment.)

But who in their right mind carves indentations into stone?

And are we seriously supposed to believe that TV crews carry precision square drills? I had no idea. I always thought they just used dowels and screws to mount things.

In my book, I wrote that these are clear signs that these stones are artificial. To which the real archaeologist responded: “So many people have been on top of the pyramid, entire TV crews—it’s obvious they chiseled out those square holes.”

Alright, fine. Let’s say you’re right. (You’re not—we’ll see in a moment.)

But who in their right mind carves indentations into stone?

And are we seriously supposed to believe that TV crews carry precision square drills? I had no idea. I always thought they just used dowels and screws to mount things.

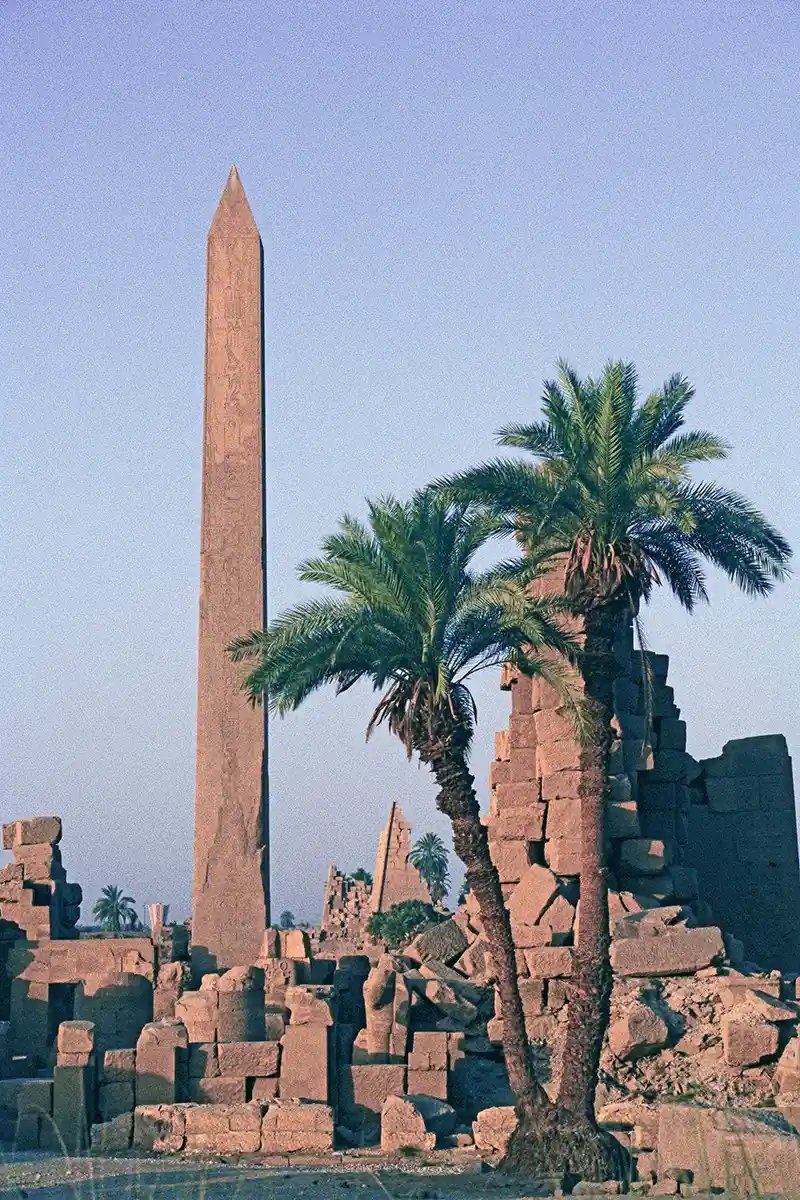

3. The easiest way to let go of the TV crews with precision square drills theory is to suddenly find hundreds of these square holes somewhere else—in this case, on the roof of the Hathor Temple in Dendera, Egypt.

BTW: These are 4k photos, tap, tap&hold and download in 4k.

So, what happened here? A film festival? On this roof?

This argument is about as solid as saying that Quenco in Peru was once a venue for ritual celebrations.

BTW: These are 4k photos, tap, tap&hold and download in 4k.

So, what happened here? A film festival? On this roof?

This argument is about as solid as saying that Quenco in Peru was once a venue for ritual celebrations.

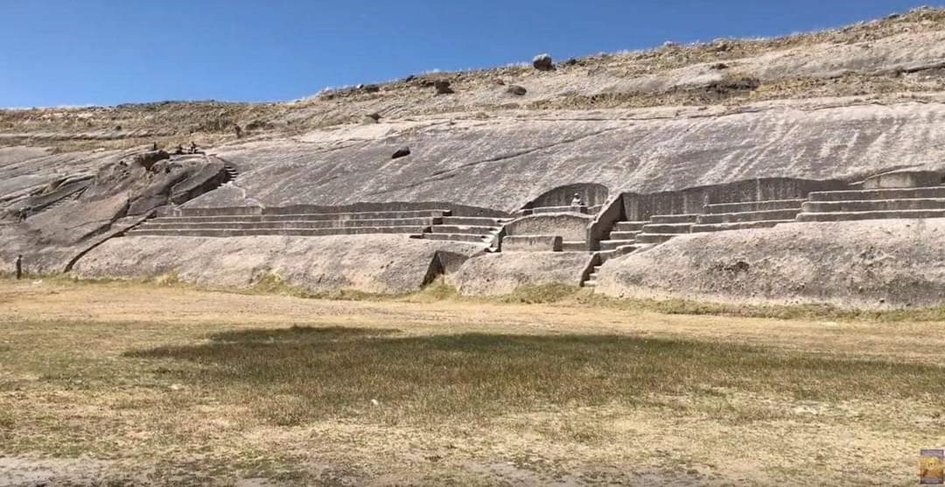

4.But what kind of ritual was it in Quenco, Peru? The Ankle-Breaking Festival, of course!

They still reenact it every year—kind of like letting bulls loose among tourists. Both are cherished traditions, after all.

Just think of the happy faces of those boarding their flights with a cast on their leg, eager to return next year for another round of the Ankle-Breaking Festival!

Oh wait… that’s not a thing.

They still reenact it every year—kind of like letting bulls loose among tourists. Both are cherished traditions, after all.

Just think of the happy faces of those boarding their flights with a cast on their leg, eager to return next year for another round of the Ankle-Breaking Festival!

Oh wait… that’s not a thing.

5.But back to Egypt.

On the roof of the Hathor Temple, we don’t just find evidence of excessive square drill usage—there’s also such a huge number of indentations spanning multiple stones that I have to say: this must have been an actual profession back in the day.

A whole guild of artisans, masters of the Great and Meaningless Indentation-Carving technique.

Holy Indentations.

Now that is a thing!

On the roof of the Hathor Temple, we don’t just find evidence of excessive square drill usage—there’s also such a huge number of indentations spanning multiple stones that I have to say: this must have been an actual profession back in the day.

A whole guild of artisans, masters of the Great and Meaningless Indentation-Carving technique.

Holy Indentations.

Now that is a thing!

6.Let’s also note that in some places, the stone joints and carvings are so precise that you couldn’t even slip a razor blade between them.

Yet another piece of evidence in favor of precision stone-cutting. (No.)

Yet another piece of evidence in favor of precision stone-cutting. (No.)

7. And we haven’t even mentioned that up here on the roof, we’re looking at poligonal masonry, a true cyclopean roof.

Why did they carve it this way? For the glory of the gods, of course!

Unfortunately, the idea that this could be some kind of concrete—not with Portland cement, but with some other binder—and that it was just poured in place is completely unacceptable.

Because, as we all know, there is no other binder besides Portland cement. There never was.

Why did they carve it this way? For the glory of the gods, of course!

Unfortunately, the idea that this could be some kind of concrete—not with Portland cement, but with some other binder—and that it was just poured in place is completely unacceptable.

Because, as we all know, there is no other binder besides Portland cement. There never was.

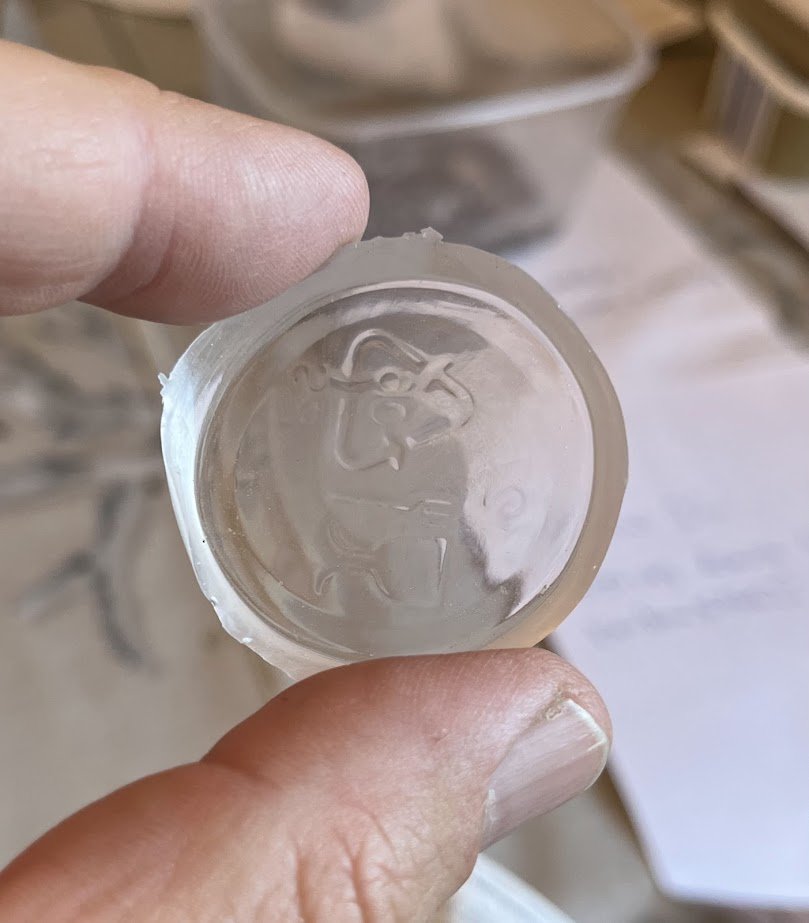

8. So what is this, then? How the heck did I manage to pour a pyramid out of artificial limestone?

I mean, that’s IM-POS-SI-BLE!

Maybe it’s not even limestone at all!

Well, if someone checks it with a mass spectrometer, they’ll find that—oh yes—it is limestone.

But here’s my take: no, not really. It’s actually a geopolymer that binds together limestone grains and limestone dust.

96% limestone, 4% binder.

And the binder? It’s made of compounds that occur naturally in limestone.

So… good luck proving otherwise.

I mean, that’s IM-POS-SI-BLE!

Maybe it’s not even limestone at all!

Well, if someone checks it with a mass spectrometer, they’ll find that—oh yes—it is limestone.

But here’s my take: no, not really. It’s actually a geopolymer that binds together limestone grains and limestone dust.

96% limestone, 4% binder.

And the binder? It’s made of compounds that occur naturally in limestone.

So… good luck proving otherwise.

9. But don’t run off just yet—I’ve got something else to show you.

These so-called wheel tracks—that aren’t wheel tracks.

The roof of the Hathor Temple is layered like a sandwich. What you see in the photo is the middle layer. It’s not the ceiling, but it’s not the final surface either.

Now, if another layer of cast limestone were to be added on top, what would a smart stonemason do to keep the two layers from slipping?

He’d roughen the surface. He’d poke it with sticks, or maybe press a wooden board into it to create a random texture—something to help the layers bond.

And once they’re set, you won’t be slipping a razor blade between them, blah blah blah…

These so-called wheel tracks—that aren’t wheel tracks.

The roof of the Hathor Temple is layered like a sandwich. What you see in the photo is the middle layer. It’s not the ceiling, but it’s not the final surface either.

Now, if another layer of cast limestone were to be added on top, what would a smart stonemason do to keep the two layers from slipping?

He’d roughen the surface. He’d poke it with sticks, or maybe press a wooden board into it to create a random texture—something to help the layers bond.

And once they’re set, you won’t be slipping a razor blade between them, blah blah blah…

10. Are we done yet? Nope, not quite.

So, how old is this temple?

It’s supposedly from the Ptolemaic period, meaning it’s not that old—only about 2,000 years.

Which leaves us with two possibilities:

Either the dating is wrong, and it’s actually twice as old—4,000 years.

Or the Egyptians never forgot the art of casting stone, but after a certain point, they just stopped using it on a large scale—maybe only for ceilings (because, let’s be honest, casting a slab is way more practical than carving one).

And if the second option is true, then the real question is:

Why do we see fewer and fewer artificial limestone surfaces as time goes on?

So, how old is this temple?

It’s supposedly from the Ptolemaic period, meaning it’s not that old—only about 2,000 years.

Which leaves us with two possibilities:

Either the dating is wrong, and it’s actually twice as old—4,000 years.

Or the Egyptians never forgot the art of casting stone, but after a certain point, they just stopped using it on a large scale—maybe only for ceilings (because, let’s be honest, casting a slab is way more practical than carving one).

And if the second option is true, then the real question is:

Why do we see fewer and fewer artificial limestone surfaces as time goes on?

11. If the knowledge wasn’t lost, then the raw materials ran out. And I think that’s exactly what happened.

Anyone who’s read my book knows that the idea of Wadi El Natrun being an unlimited natron source to this day is nothing more than a myth.

I used to believe that story too. But the truth is, that deposit was exhausted thousands of years ago.

Somebody mined out every last bit of natron from that lake system.

Gone. Just—gone.

And if there’s no natron, how are you supposed to cast millions more artificial stones?

You don’t. You hold back. You only use artificial stone where it’s absolutely necessary or makes the most sense.

This is an amazing story. I gathered everything I could find on the topic and packed it into 372 pages.

It’s one of those “once you see it, you can’t unsee it” things.

And once you’ve read it—you can’t unread it.

Anyone who’s read my book knows that the idea of Wadi El Natrun being an unlimited natron source to this day is nothing more than a myth.

I used to believe that story too. But the truth is, that deposit was exhausted thousands of years ago.

Somebody mined out every last bit of natron from that lake system.

Gone. Just—gone.

And if there’s no natron, how are you supposed to cast millions more artificial stones?

You don’t. You hold back. You only use artificial stone where it’s absolutely necessary or makes the most sense.

This is an amazing story. I gathered everything I could find on the topic and packed it into 372 pages.

It’s one of those “once you see it, you can’t unsee it” things.

And once you’ve read it—you can’t unread it.

Here is the book with concrete examples from history when humanity almost killed itself in a frenzy of production:

a.co/d/2x9vGcj

a.co/d/2x9vGcj

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh