Ancient Mysteries’ Researcher🗿Inventor of The Natron Theory🧂Solved the artificial granite problem 🪨 with caveman materials only. Author: The Natron Theory 📔

2 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

2. First, let’s see how I killed the long, boring hours of the Christmas break.

2. First, let’s see how I killed the long, boring hours of the Christmas break.

2. Ancient Croatia

2. Ancient Croatia

2. Sure, you can buy 5 grams for 50 dollars on Amazon, but trying to cast a multi-ton stone block with that… well, it’s not exactly cost-effective.

2. Sure, you can buy 5 grams for 50 dollars on Amazon, but trying to cast a multi-ton stone block with that… well, it’s not exactly cost-effective.

First Act

First Act

2. And while I was thinking about this, I remembered a much earlier experiment when I tried to make glass lenses from silica gel.

2. And while I was thinking about this, I remembered a much earlier experiment when I tried to make glass lenses from silica gel.

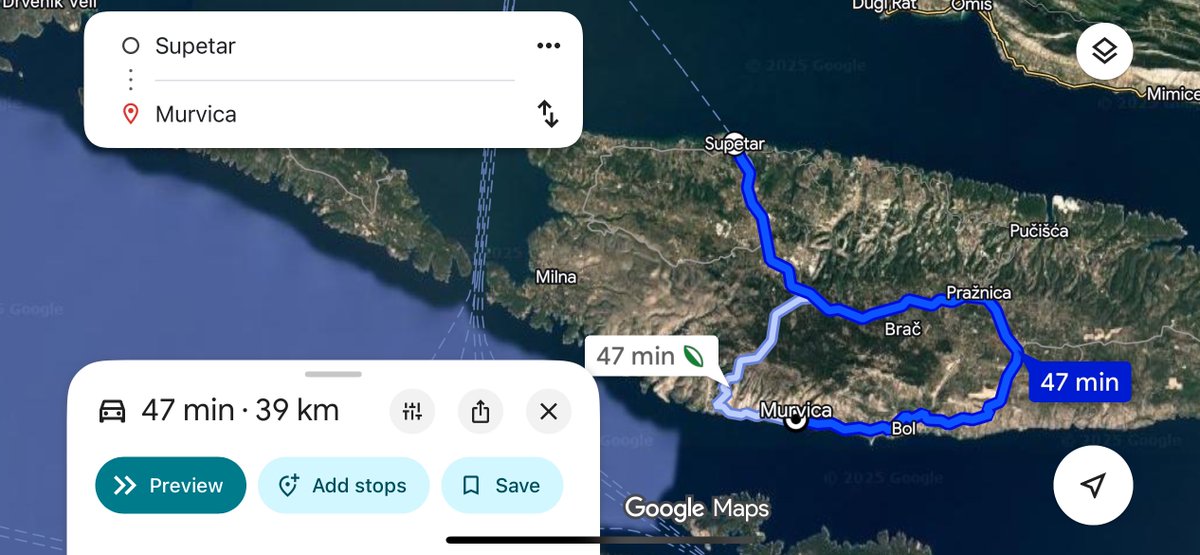

2. Before I answer that, a bit of geography. Just off the coast from Split are a bunch of small islands. One of the larger ones is Brač.

2. Before I answer that, a bit of geography. Just off the coast from Split are a bunch of small islands. One of the larger ones is Brač.

2. It’s a limestone block in the basement of Diocletian’s Palace in Split — specifically, a lintel. This will be hugely significant later on.

2. It’s a limestone block in the basement of Diocletian’s Palace in Split — specifically, a lintel. This will be hugely significant later on.

2. So I suddenly came up with three minimal conditions that all need to be met for casting to even be a possibility. I’ll be applying these same criteria to the Temple of Jupiter in the city of Split as well later on.

2. So I suddenly came up with three minimal conditions that all need to be met for casting to even be a possibility. I’ll be applying these same criteria to the Temple of Jupiter in the city of Split as well later on.

2. By now, the ash has long since dried—remember, I started the experiment two weeks ago.

2. By now, the ash has long since dried—remember, I started the experiment two weeks ago.

2. Neopolymer — Norway spruce ash + waterglass.

2. Neopolymer — Norway spruce ash + waterglass.

2. So, it all started when I etched a piece of granite using molten natron in a grill chimney.

2. So, it all started when I etched a piece of granite using molten natron in a grill chimney.

2. First Act

2. First Act

2. This place is the ancient Peruvian salt evaporation site, Salinas de Maras, where massive amounts of salt have been produced for thousands of years.

2. This place is the ancient Peruvian salt evaporation site, Salinas de Maras, where massive amounts of salt have been produced for thousands of years.

2. In this image, we can spot all kinds of interesting details—from the impressions spanning multiple stones (top right, orange fram) to the skillful use of a square drill (bottom left, green frame).

2. In this image, we can spot all kinds of interesting details—from the impressions spanning multiple stones (top right, orange fram) to the skillful use of a square drill (bottom left, green frame).

2. In this image, we can spot all kinds of interesting details—from the impressions spanning multiple stones (top right, orange fram) to the skillful use of a square drill (bottom left, green frame).

2. In this image, we can spot all kinds of interesting details—from the impressions spanning multiple stones (top right, orange fram) to the skillful use of a square drill (bottom left, green frame).

2. Why is this important? Because he collected it at the top (‼️) of the great pyramid some 20 years ago

2. Why is this important? Because he collected it at the top (‼️) of the great pyramid some 20 years ago

2. To understand the tale, we need to rewind about 80–90 years—to the era of vacuum tubes.

2. To understand the tale, we need to rewind about 80–90 years—to the era of vacuum tubes.

2. For the longest time, I didn’t realize that this pattern wasn’t made for aesthetics—it came about because something had to be cast around and then patched up later.

2. For the longest time, I didn’t realize that this pattern wasn’t made for aesthetics—it came about because something had to be cast around and then patched up later.

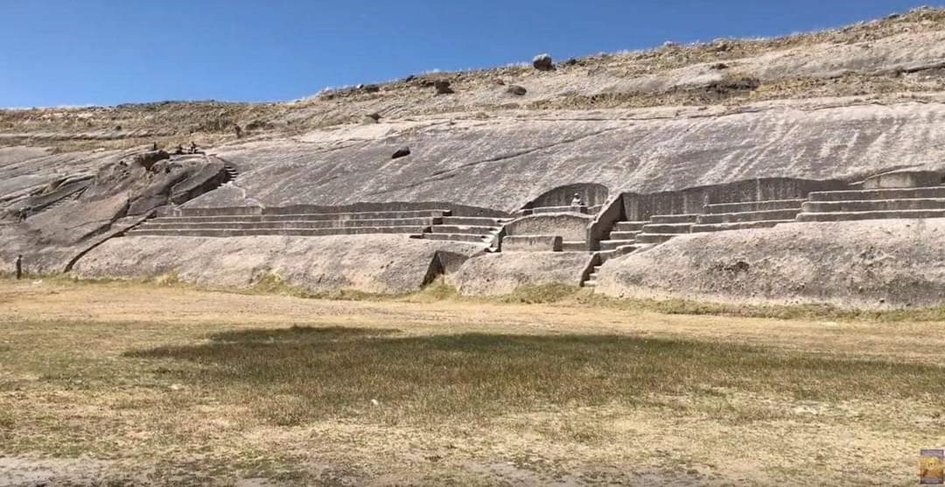

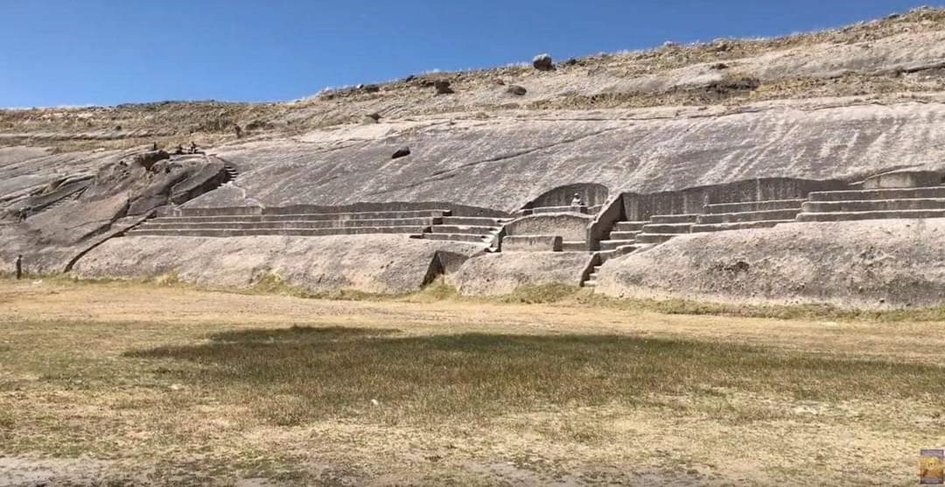

2. Bench in Cusco

2. Bench in Cusco