The Wall Street Journal just published the FDA's Opinion piece-length rationale for banning talc.

I was happy to see they were citing studies, but after I read the studies, I was dismayed:

The FDA fell victim to bad science, and they might ban talcum powder because of it!

🧵

I was happy to see they were citing studies, but after I read the studies, I was dismayed:

The FDA fell victim to bad science, and they might ban talcum powder because of it!

🧵

The evidence cited in the article is

- A 2019 meta-analysis

- A review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)

- A 2019 cohort study from Taiwan

Let's go through each of these and see if the FDA's evidence holds water.

- A 2019 meta-analysis

- A review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)

- A 2019 cohort study from Taiwan

Let's go through each of these and see if the FDA's evidence holds water.

The first piece of evidence they cite is a meta-analysis, and it's a doozy.

The study includes 27 estimates of the observational association between talc use and ovarian cancer rates.

Three estimates come from cohort studies. Those are fine. The problem is the 24 other studies.

The study includes 27 estimates of the observational association between talc use and ovarian cancer rates.

Three estimates come from cohort studies. Those are fine. The problem is the 24 other studies.

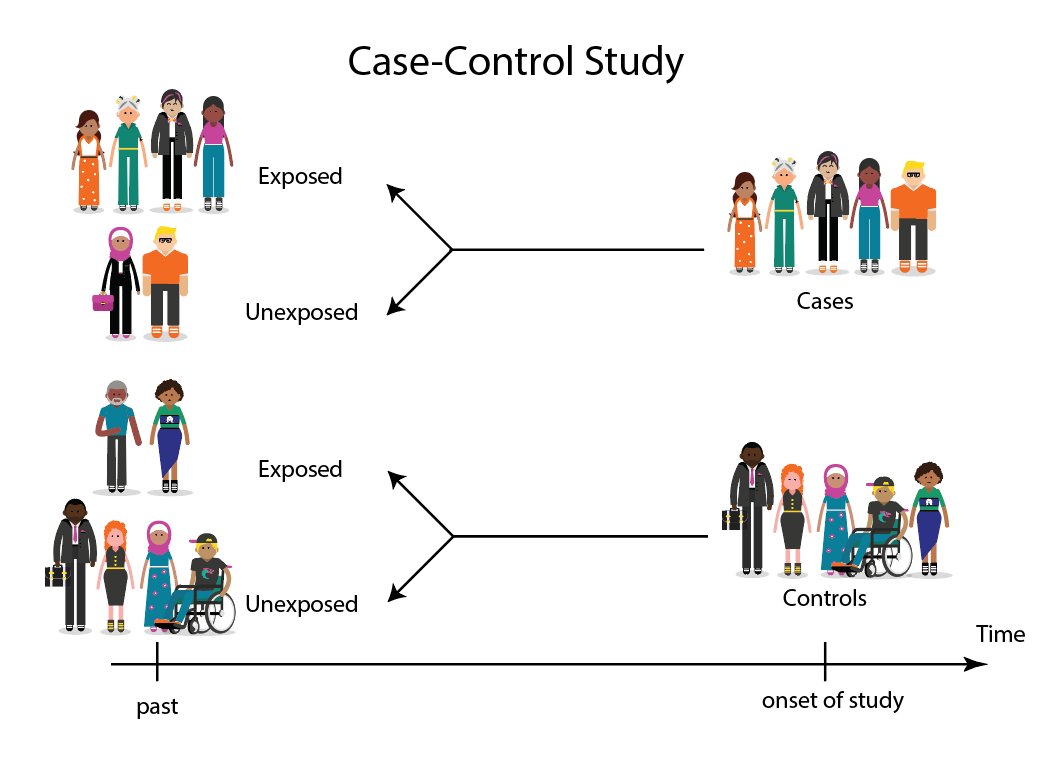

The 24 other studies are "case-control" studies, where you compare people who have ovarian cancer to those who do not in terms of their self-reported use of talc in the past.

The problem here is the quality of those self-reports.

The problem here is the quality of those self-reports.

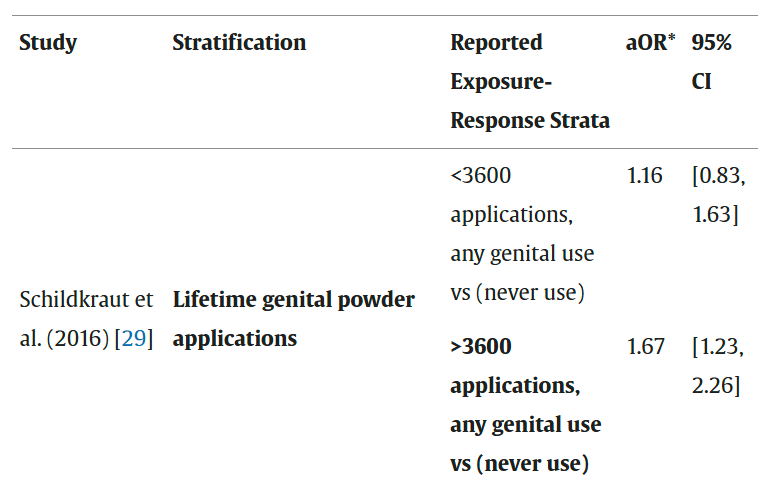

Consider an example from the study

Schildkraut et al. asked people aged 20 to 79 to report how much talc they had used on their genitals over their entire lifetimes

Comparing people with <3600 uses to never-users, no significant effect. Comparing people with >3600 uses? Alarm!

Schildkraut et al. asked people aged 20 to 79 to report how much talc they had used on their genitals over their entire lifetimes

Comparing people with <3600 uses to never-users, no significant effect. Comparing people with >3600 uses? Alarm!

But, wait...

Do you remember how much talc you've used over your entire lifetime? Do you really think you can reliably tell an interviewer how much talc you've used over the past, say, 40 years?

If you answer "Yes", then that probably means you're someone who's never used talc.

Do you remember how much talc you've used over your entire lifetime? Do you really think you can reliably tell an interviewer how much talc you've used over the past, say, 40 years?

If you answer "Yes", then that probably means you're someone who's never used talc.

If you answer "No", then that means you've probably used talc, or had it used on you as a baby.

People, as it turns out, do not have good enough memories for these self-reports to be reliable.

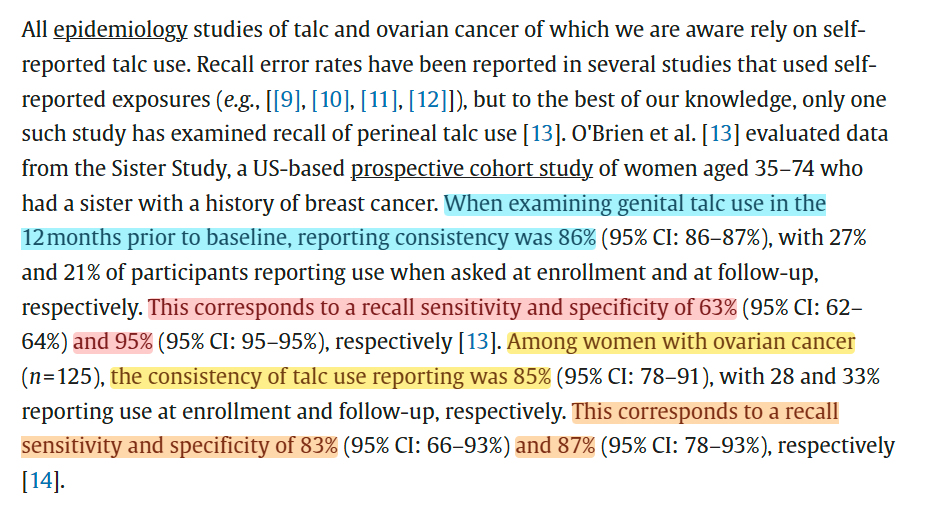

We know this for talc use based on a study that reported one-year recall accuracy.

People, as it turns out, do not have good enough memories for these self-reports to be reliable.

We know this for talc use based on a study that reported one-year recall accuracy.

One year is a lot less to remember than a whole lifetime, so this probably oversells just how well people remembered their talc use in that 2016 study I in the meta-analysis.

We know this as a stylized fact: the longer the recall period, the less reliable the recall!

We know this as a stylized fact: the longer the recall period, the less reliable the recall!

The way to get around this issue is...

1. Explicit analysis of the raw case-control data, which we don't have

2. Or sensitivity analyses!

Sensitivity analyses basically go "What would the effect be like if people erred at certain rates?"

We'll use those one-year recall rates.

1. Explicit analysis of the raw case-control data, which we don't have

2. Or sensitivity analyses!

Sensitivity analyses basically go "What would the effect be like if people erred at certain rates?"

We'll use those one-year recall rates.

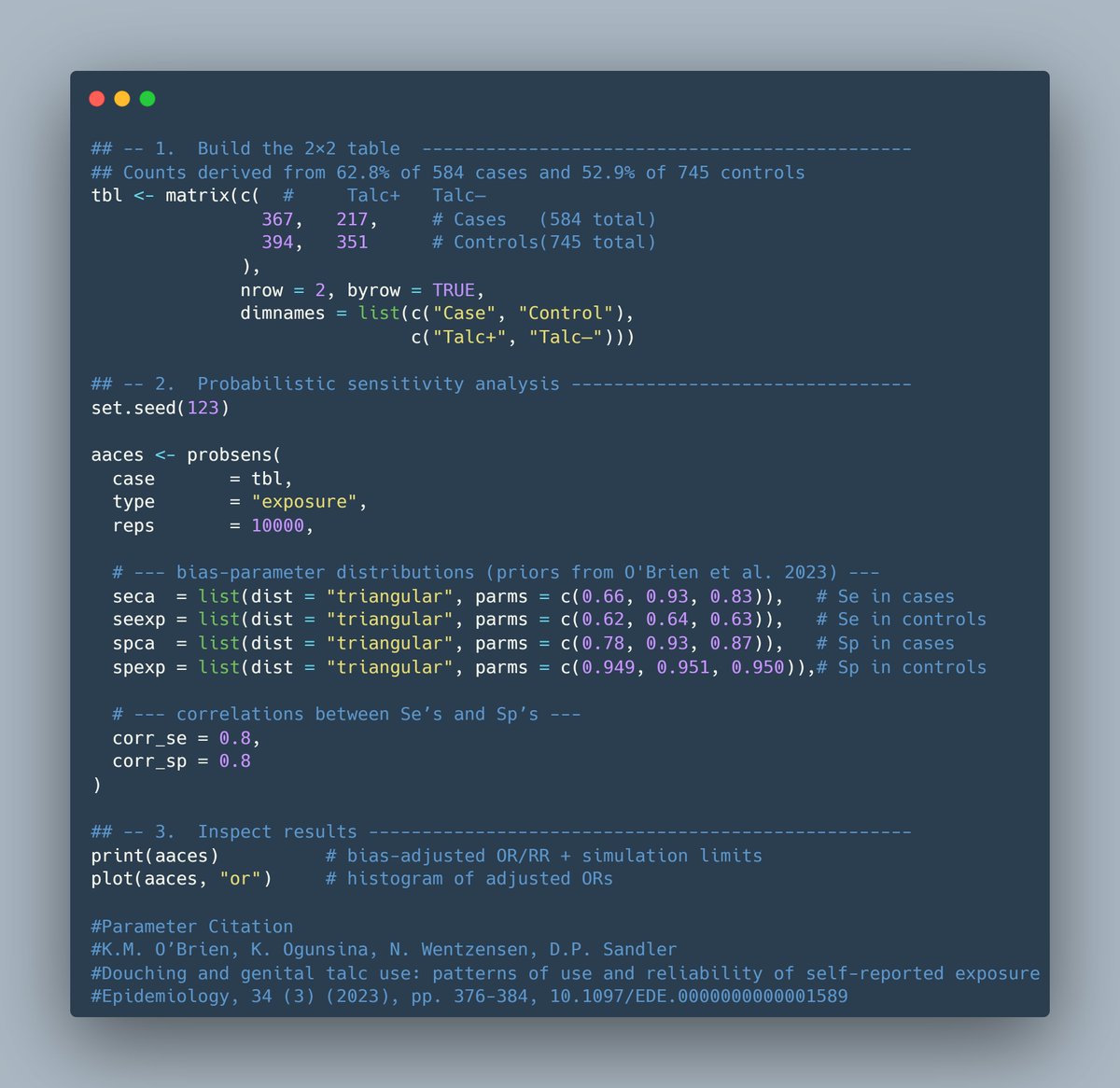

For my purposes, I'm going to be using the episenr R package, but this analysis can be easily implemented to similar effect in a variety of ways.

This is how my code looks, if you want to go run this yourself.

This adapts the outdated code from Goodman et al. (2024).

This is how my code looks, if you want to go run this yourself.

This adapts the outdated code from Goodman et al. (2024).

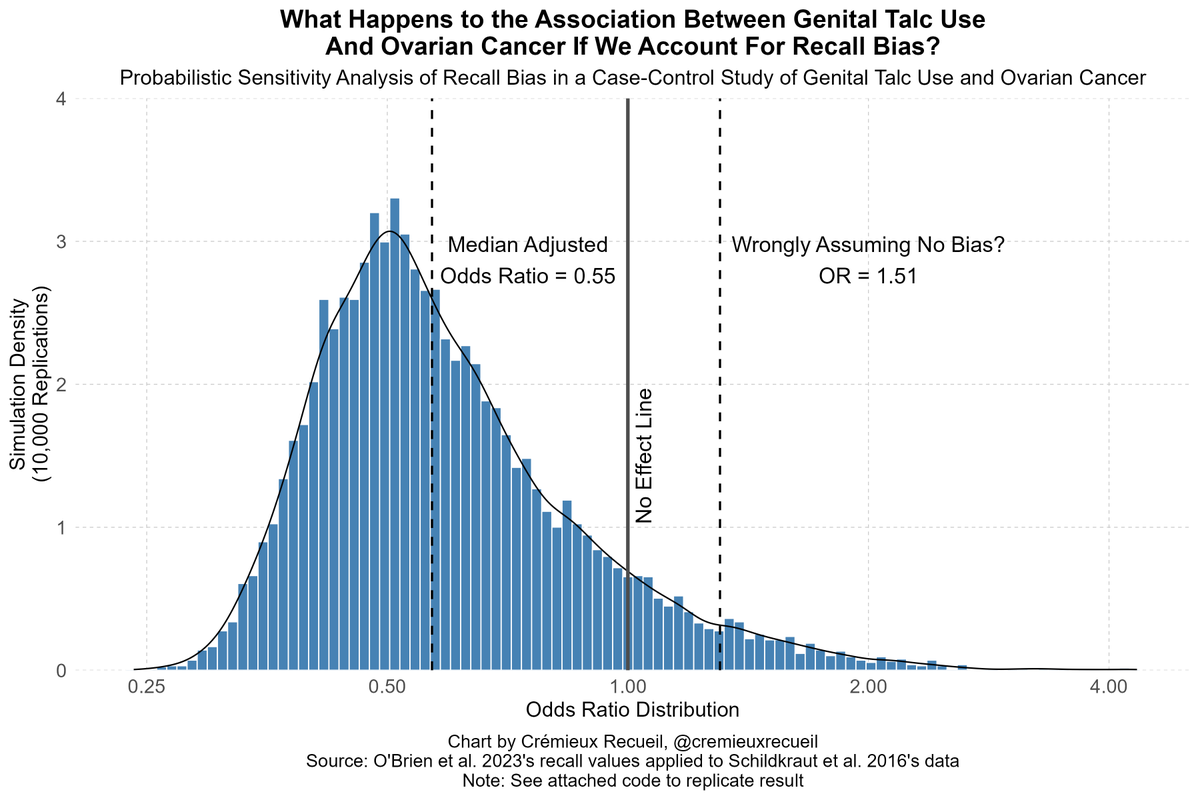

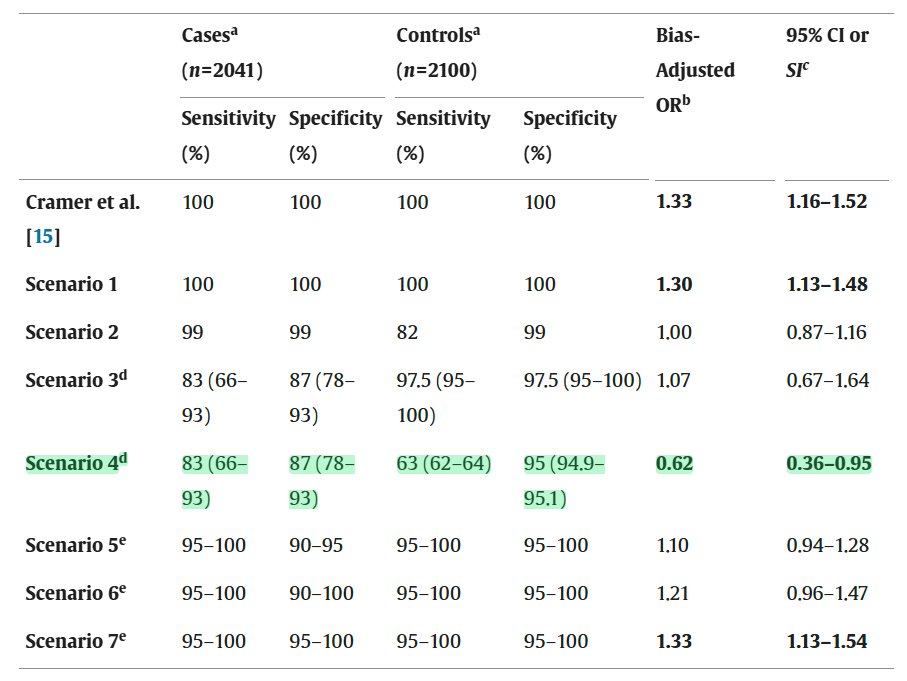

If we run this code, the achieved odds ratio actually goes in the opposite direction!

If you run it assuming accuracy, it returns the same result as the baseline for the study.

But the study is two things: wrong about magnitudes and wrong about variance.

If you run it assuming accuracy, it returns the same result as the baseline for the study.

But the study is two things: wrong about magnitudes and wrong about variance.

The variance in question has to do with the certainty implied by assuming no recall bias.

But if people's memories are off, our certainty must decline. As such, the effect in realistic sensitivity analyses will almost-certainly be nonsignificant, as it was in my simulation.

But if people's memories are off, our certainty must decline. As such, the effect in realistic sensitivity analyses will almost-certainly be nonsignificant, as it was in my simulation.

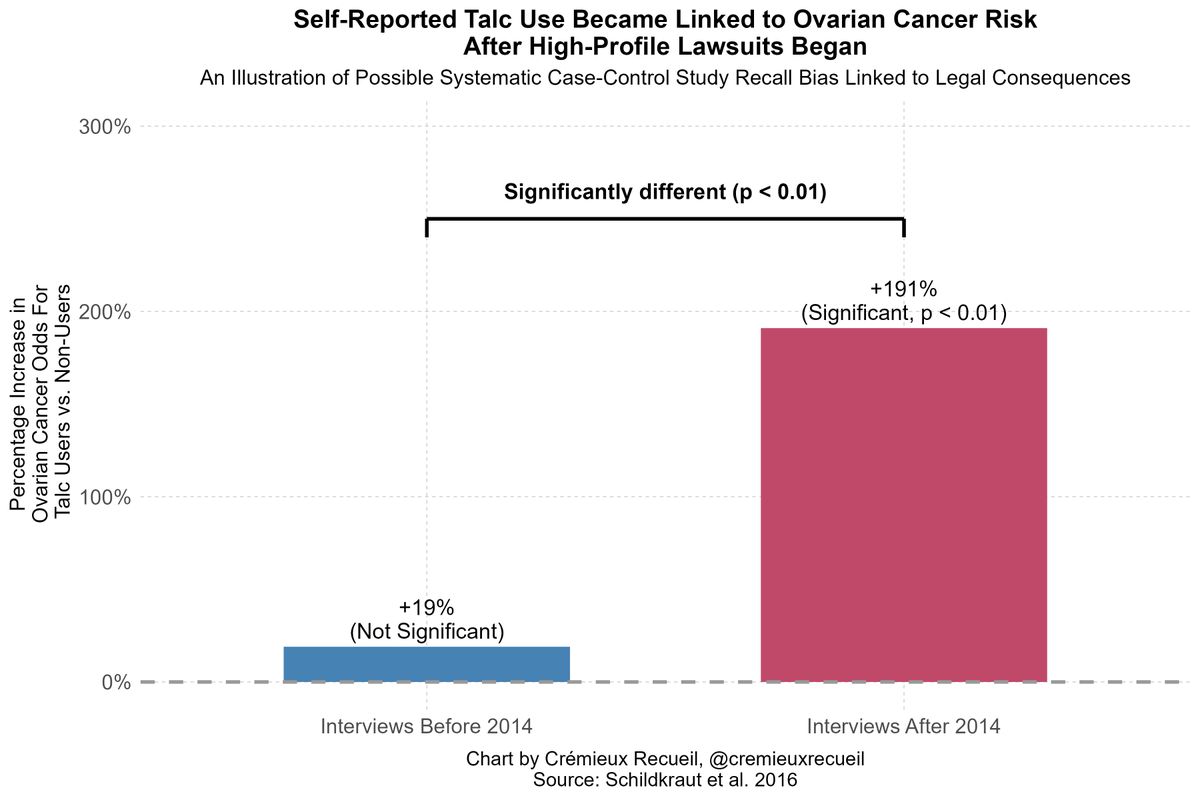

But the other thing to keep in mind is that reports about talc use can be systematically biased.

In the study I just reanalyzed, the authors also split the results by survey years before and after 2014.

Why? Because of two high-profile talc class action cases.

In the study I just reanalyzed, the authors also split the results by survey years before and after 2014.

Why? Because of two high-profile talc class action cases.

In this dataset, the association with talc only emerged after people "learned" talc was associated with cancer in courts.

Quite likely, what happened is that people suffering from ovarian cancer mentally exaggerated their talc use after learning it might've been a risk factor!

Quite likely, what happened is that people suffering from ovarian cancer mentally exaggerated their talc use after learning it might've been a risk factor!

Back to what the FDA cited.

The meta-analysis said there was an odds ratio of 1.28 in favor of an association between talc powder use and ovarian cancer.

For case-control studies, this was 1.32 (1.24-1.40) and for cohort studies, which are not biased by recall, 1.06 (0.9-1.25).

The meta-analysis said there was an odds ratio of 1.28 in favor of an association between talc powder use and ovarian cancer.

For case-control studies, this was 1.32 (1.24-1.40) and for cohort studies, which are not biased by recall, 1.06 (0.9-1.25).

In short, the studies not affected by recall bias showed no evidence of an effect at baseline.

If we correct all of the case-control studies with available data and even if we don't correct the ones without the required data by filling in from the data in the other studies...

If we correct all of the case-control studies with available data and even if we don't correct the ones without the required data by filling in from the data in the other studies...

We get no effect too! (OR = ~0.96, not sig).

We get no effect in case-control studies alone, we get no effect in meta-analysis of the case-control and cohort studies.

This matches up with what was found when another of the studies in the meta-analysis was reanalyzed last year.

We get no effect in case-control studies alone, we get no effect in meta-analysis of the case-control and cohort studies.

This matches up with what was found when another of the studies in the meta-analysis was reanalyzed last year.

That meta-analysis was the strongest evidence the FDA cited, and it didn't hold up after a simple, realistic accounting for the fact that you can't trust people to remember how much talc they used sometimes over an entire, sometimes quite long, life.

What about the rest?

What about the rest?

I'm going to skip to the third piece of evidence first.

This is a 2019 study of a million people in Taiwan, supporting a link between talc use and gastrointestinal cancer.

Ostensibly.

I want to start by noting that the author has been banging on the talc drum for years.

This is a 2019 study of a million people in Taiwan, supporting a link between talc use and gastrointestinal cancer.

Ostensibly.

I want to start by noting that the author has been banging on the talc drum for years.

CJ Chang has written multiple studies linking talc to different types of cancers.

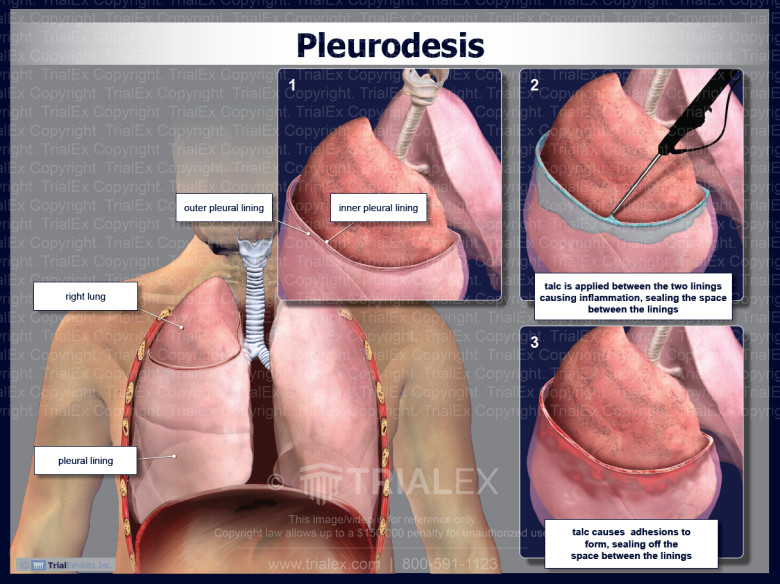

Understanding their lack of realism requires understanding, first, that talc is used in pleurodesis, where the space between the lungs and chest wall is filled with talc.

Understanding their lack of realism requires understanding, first, that talc is used in pleurodesis, where the space between the lungs and chest wall is filled with talc.

This is about the most direct exposure possible that should cause cancer.

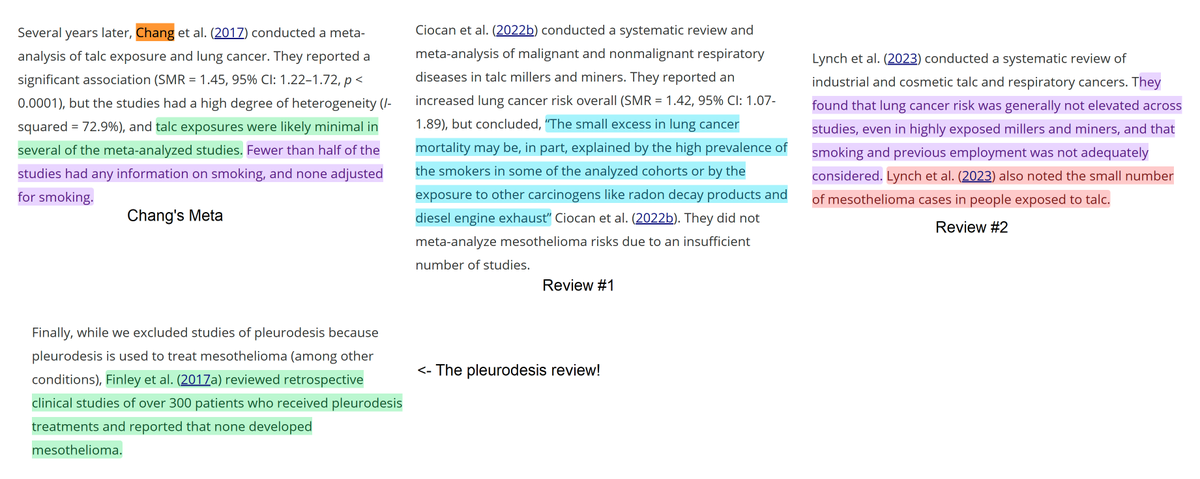

Without citing pleurodesis studies, Chang says... talc is related to lung cancer.

But, pleurodesis reviews say "no" and other reviews like Chang's note critical confounders afoot, which Chang ignored.

Without citing pleurodesis studies, Chang says... talc is related to lung cancer.

But, pleurodesis reviews say "no" and other reviews like Chang's note critical confounders afoot, which Chang ignored.

Those lung cancer conclusions do not hold up in humans.

But Chang is still on the case!

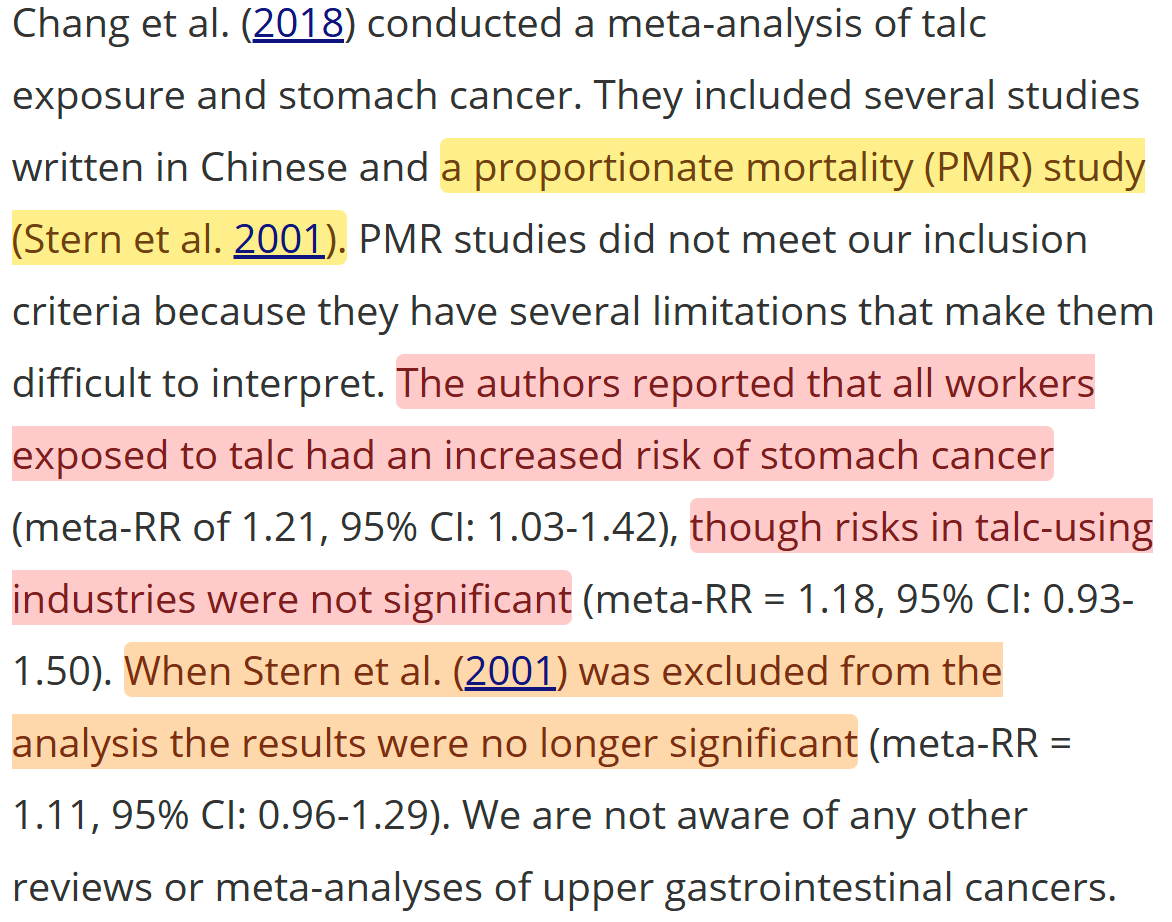

He linked it to gastrointestinal cancer in another meta-analysis. But this was critically-dependent on a study that assumes an effect size and backtracks to an estimate.

But Chang is still on the case!

He linked it to gastrointestinal cancer in another meta-analysis. But this was critically-dependent on a study that assumes an effect size and backtracks to an estimate.

Chang's prior results have all been very sensitive to things that should've been obvious to Chang in the moment and they've been unsuitable for informing us.

The case is no different for the 2019 study.

This study was not so much of talc use, as of Chinese herbal medicine use.

The case is no different for the 2019 study.

This study was not so much of talc use, as of Chinese herbal medicine use.

Chinese herbal medicines include much more that could be carcinogenic than just talc, making this an unsuitable exposure.

This stuff is also associated with a bunch of other practices, and the bundle of bad that comes with having low socioeconomic status.

This stuff is also associated with a bunch of other practices, and the bundle of bad that comes with having low socioeconomic status.

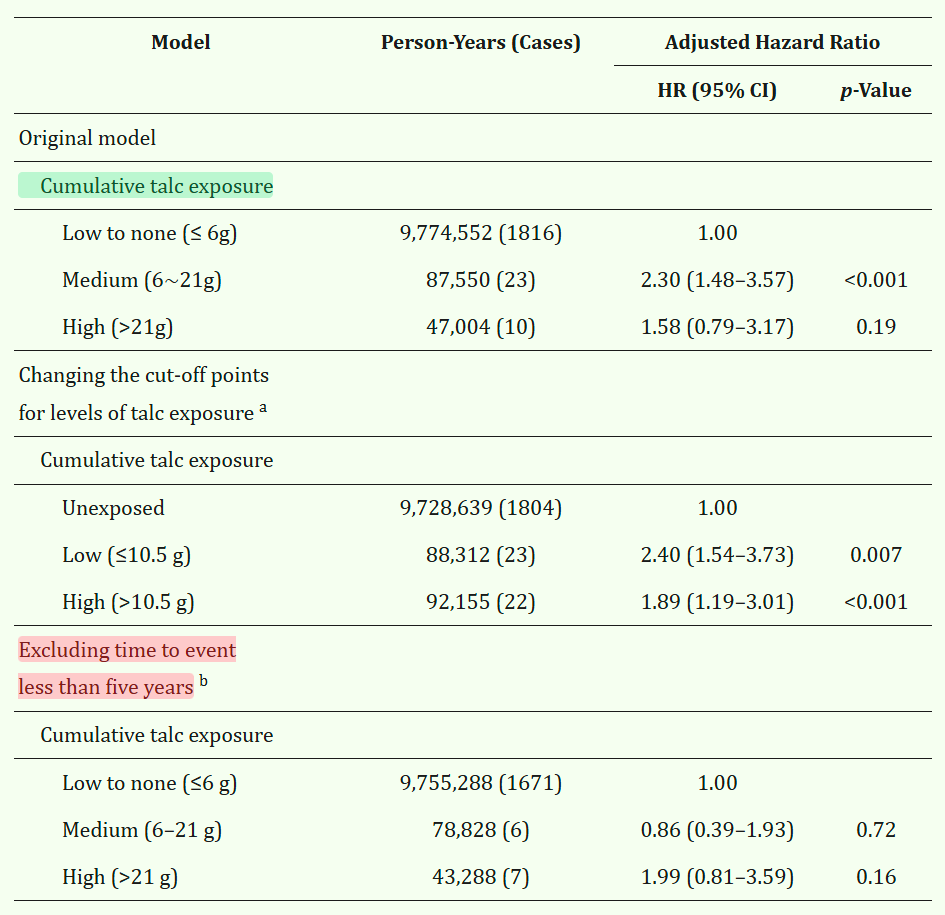

Nevertheless, if we look through Chang's FDA-cited results, we get something curious.

Firstly, there's suggestive evidence of a nonlinear dose-response curve. Secondly, if you say 'maybe talc doesn't immediately lead to cancer', the effect goes null.

Firstly, there's suggestive evidence of a nonlinear dose-response curve. Secondly, if you say 'maybe talc doesn't immediately lead to cancer', the effect goes null.

The Taiwanese result the FDA cited turned out to be incredibly fragile.

It's inconsistent with the rest of the literature and it lacks important controls like for smoking and drinking and there's no plausible gastro mechanism to inhalation risk, so this is not surprising.

It's inconsistent with the rest of the literature and it lacks important controls like for smoking and drinking and there's no plausible gastro mechanism to inhalation risk, so this is not surprising.

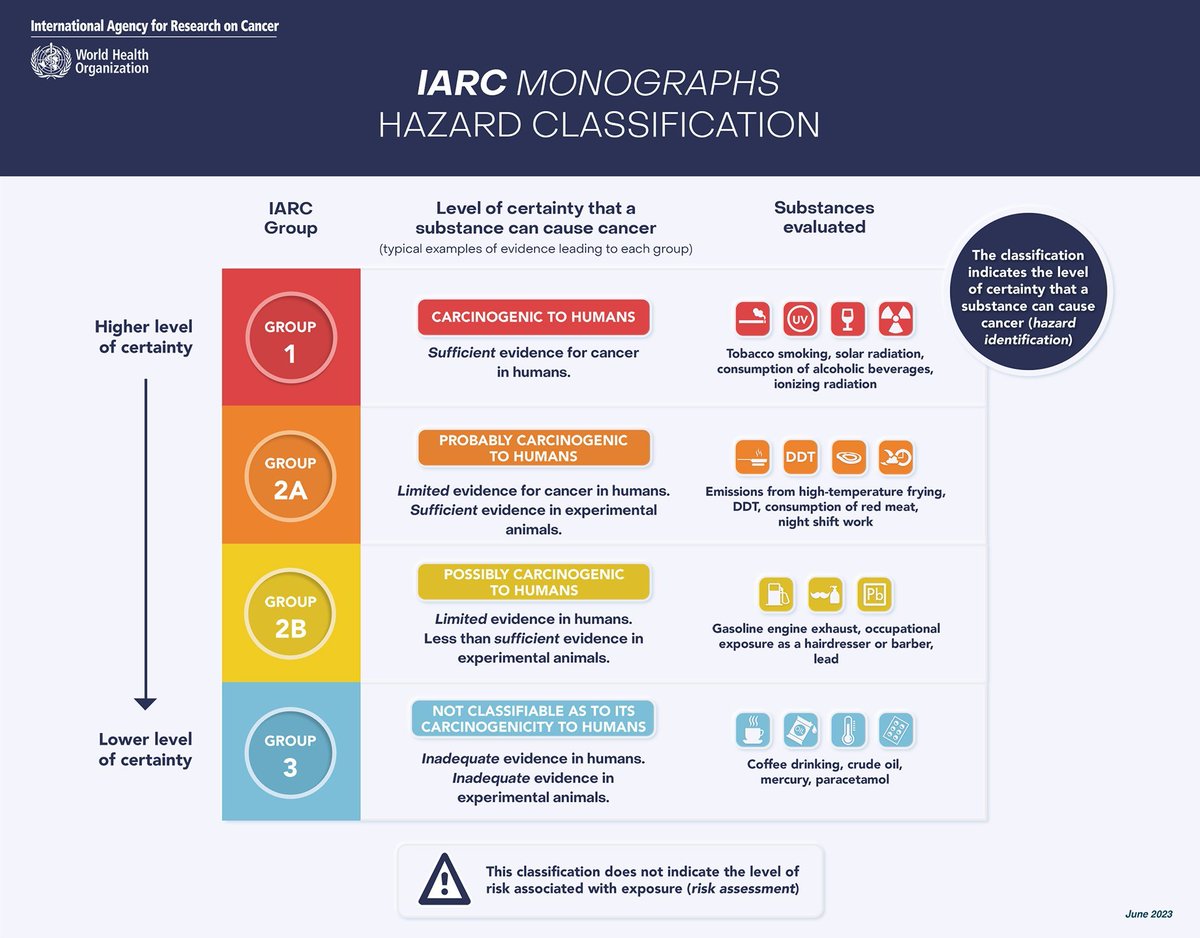

Now we have to talk about the last piece of evidence cited by the FDA: statements of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

If you've read some of my earlier threads, you'll know they're widely misunderstood. That's because the IARC deals with theoretical risk.

If you've read some of my earlier threads, you'll know they're widely misunderstood. That's because the IARC deals with theoretical risk.

You see that little note there in the bottom of that image?

They say that because the IARC reviews lots of pieces of evidence to draw associations, but they don't make them quantitative.

This is why they can say, for example, that aspartame is potentially carcinogenic.

They say that because the IARC reviews lots of pieces of evidence to draw associations, but they don't make them quantitative.

This is why they can say, for example, that aspartame is potentially carcinogenic.

Aspartame cannot be carcinogenic unless you're injecting super-massive quantities.

But we've done that in some human experiments, and while there was nausea, there was nothing else.

But the IARC follows a "throw stuff against the wall" strategy:

But we've done that in some human experiments, and while there was nausea, there was nothing else.

But the IARC follows a "throw stuff against the wall" strategy:

https://x.com/cremieuxrecueil/status/1914889642505064544

Part of the IARC's proclivity for unwarranted conclusions comes from the fact that they are weaponized by legal firms.

Christopher Portier, an expert for the IARC, is an example. He was hired by two law firms, seemingly to fraudulently rigged the IARC's report on glyphosate.

Christopher Portier, an expert for the IARC, is an example. He was hired by two law firms, seemingly to fraudulently rigged the IARC's report on glyphosate.

The report was initially not on glyphosate, but on an entirely different set of herbicides, and when he joined up, he tagged it on for some reason and then removed the findings showing it was not carcinogenic.

This style of fraud at the IARC is common.

This style of fraud at the IARC is common.

https://x.com/cremieuxrecueil/status/1927915527877398563

What's the basis of the IARC's statements on talc, which the FDA cites?

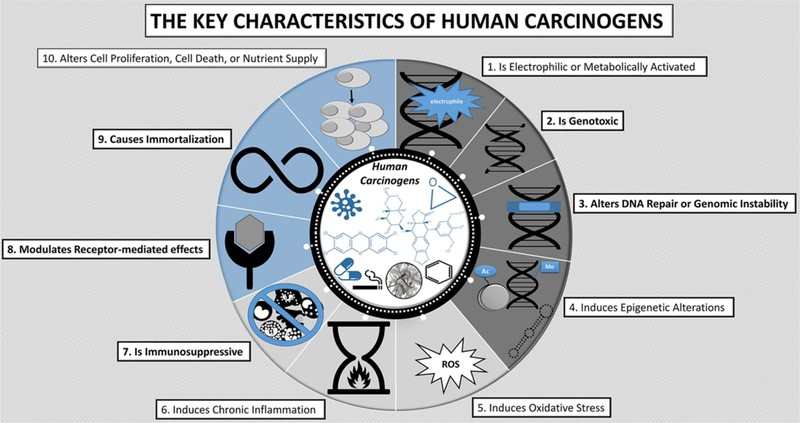

The aforementioned non-supportive ovarian cancer evidence for humans; evidence from animals; talc having three "key characteristics of carcinogens" or KCCs.

Here are the IARC's KCCs:

The aforementioned non-supportive ovarian cancer evidence for humans; evidence from animals; talc having three "key characteristics of carcinogens" or KCCs.

Here are the IARC's KCCs:

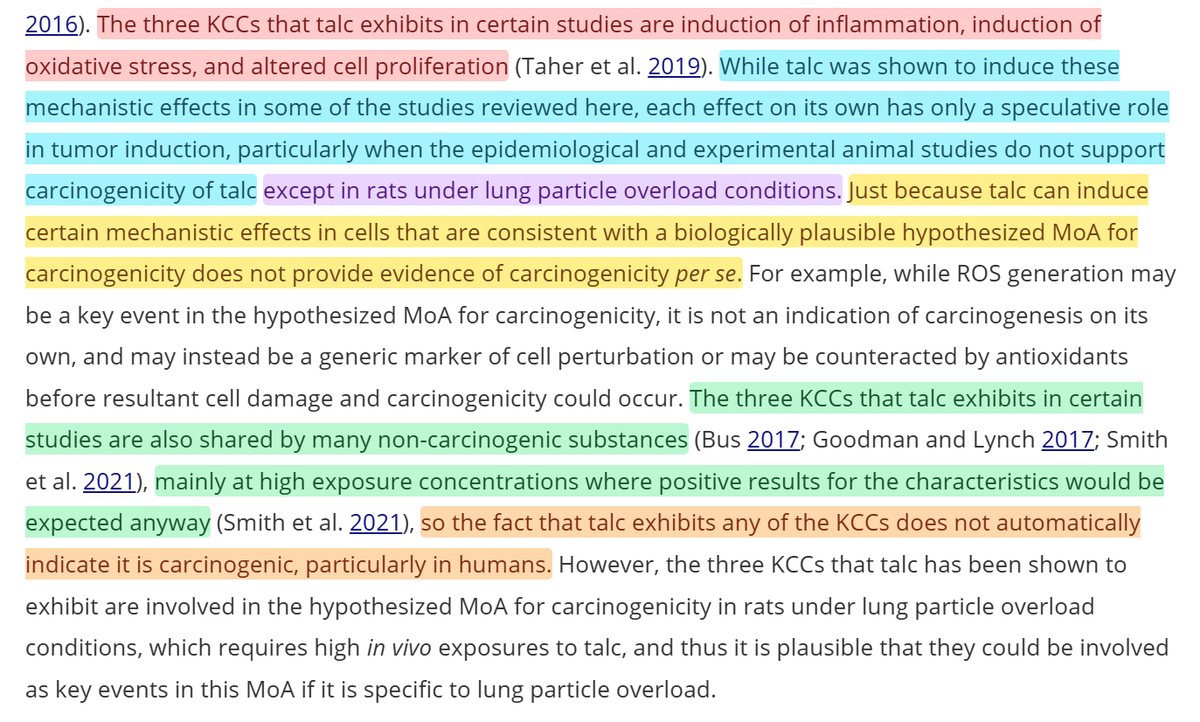

These "key characteristics" have drawn a lot of ire from the field, because the IARC weaponizes them.

The IARC finds an example in a perhaps unrealistic setting where a KCC might show up, then says the substance has that KCC.

No care for replications, no care for relevance.

The IARC finds an example in a perhaps unrealistic setting where a KCC might show up, then says the substance has that KCC.

No care for replications, no care for relevance.

The really bad thing about KCCs is that you can find unrealistic evidence that lots of confirmed non-carcinogenic substances demonstrate them.

That is, they are not inherent signs of carcinogenicity.

And in most experiments, they don't show up for talc:

That is, they are not inherent signs of carcinogenicity.

And in most experiments, they don't show up for talc:

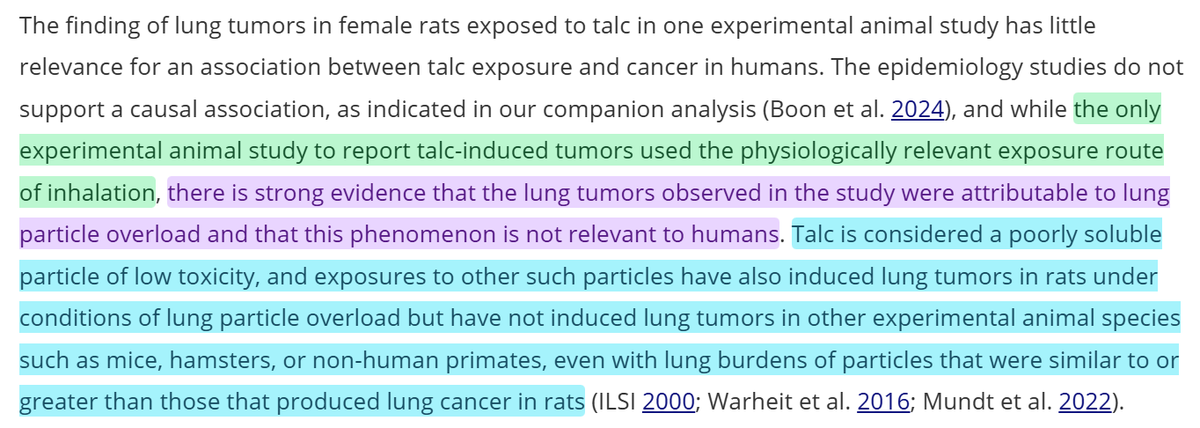

If you read the above paragraph, you'll notice something else.

There is no experimental evidence talc is carcinogenic in any animals, except those exhibiting "lung particle overload".

What's that? Who cares, because it's never observed in non-rat models.

There is no experimental evidence talc is carcinogenic in any animals, except those exhibiting "lung particle overload".

What's that? Who cares, because it's never observed in non-rat models.

The IARC:

1. Acknowledged the flaws of the human evidence, but failed to correct them, choosing to run with them instead

2. Failed to acknowledge the lack of generalizability of the limited animal evidence

3. Misled with their useless in-house metrics.

Carcinogenicity!

1. Acknowledged the flaws of the human evidence, but failed to correct them, choosing to run with them instead

2. Failed to acknowledge the lack of generalizability of the limited animal evidence

3. Misled with their useless in-house metrics.

Carcinogenicity!

What we have here is a bad situation.

It takes a lot of effort to read through all the evidence on a compound's "risk" or the plausibility of any risk.

Because of this, if you strike first—publishing a rotten meta-analysis, or overinterpreting bad animal studies—you can win.

It takes a lot of effort to read through all the evidence on a compound's "risk" or the plausibility of any risk.

Because of this, if you strike first—publishing a rotten meta-analysis, or overinterpreting bad animal studies—you can win.

The FDA has been misled because the scientific literature is not careful, and it's hard to not be selective when you're not tasked with sitting down and doing a very comprehensive review.

I get it! The regulators are trying to go fast, operate with limited info, defer not demur.

I get it! The regulators are trying to go fast, operate with limited info, defer not demur.

They suspect that organizations like the IARC would not botch evidence reviews, so they defer.

A big recent agenda item is to demur conventional wisdom and reviews, so reviews that raise concerns get preference.

All too understandable.

A big recent agenda item is to demur conventional wisdom and reviews, so reviews that raise concerns get preference.

All too understandable.

But we cannot do that if we care about Americans' health.

The FDA has a duty to get this right, to avoid the bad evidence that bad actors produce and cite at them, and to pore over every little detail, as so many regulators have done before them.

The FDA has a duty to get this right, to avoid the bad evidence that bad actors produce and cite at them, and to pore over every little detail, as so many regulators have done before them.

Millions of people use talc

Talc is also obviously safe, and we've known it was safe for ages. All the real risk is from adulterated stuff, and that's regulated by the FDA anyway. Target that!

Or ban a harmless substance and do a disservice to the American people. FDA's choice!

Talc is also obviously safe, and we've known it was safe for ages. All the real risk is from adulterated stuff, and that's regulated by the FDA anyway. Target that!

Or ban a harmless substance and do a disservice to the American people. FDA's choice!

I hope to see the FDA getting this right. If they don't, then bad science will have won and Americans will suffer for it.

Sources:

wsj.com/opinion/the-fd… (Archive link: archive.md/mQM3O)

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/2…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

dhaine.github.io/episensr/

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC64…

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

Sources:

wsj.com/opinion/the-fd… (Archive link: archive.md/mQM3O)

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/2…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

dhaine.github.io/episensr/

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC64…

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh