I think Brad Pitt's suit is interesting. And I'll tell you why. 🧵

https://twitter.com/KevDublin/status/1933672629761946073

This is the suit in question. It's a bespoke suit by Anderson & Sheppard in London. The cloth is a 60/40 mohair-wool blend from Standeven's "Carnival" book. The stylist was George Cortina.

To understand why this suit is interesting, you have to know a bit about tailoring history

To understand why this suit is interesting, you have to know a bit about tailoring history

In the early 20th century, Dutch-English tailor Frederick Scholte noticed that a man could be made to look more athletic if he belted up his guard's coat, puffing out the chest and nipping the waist. So he built this idea into his patterns. Thus the "drape cut" war born.

Scholte was an ill-tempered man with strong opinions. He mostly refused to dress entertainers. He turned down a man because he arrived in a flashy car. When the wife of a US ambassador brought up an issue at a fitting, he ripped the coat off the man and threw both of them out.

But boy, did he know how to cut! He dressed some of the most stylish men of his day, such as the Duke of Windsor. The Duke was so afraid of his ill-tempered, opinionated tailor that he dared not ask for belt loops on trousers, sneakily getting them from a tailor in NYC instead.

The drape cut is distinguished by its soft English shoulders (softer than padded English coats, but not as soft as Neapolitan tailoring). It also has a full chest. Take a look at these two coats: the left is called a "clean" chest; the right is called a drape cut (made by A&S)

The term "drape" refers to how excess fabric "drapes" along the armhole. This is done through drafting and tailoring. The chest piece inside is cut on a bias, so that the chest is more rounded. On a clean chest, the garment would sit closer to the body. This is by Steed Bespoke:

Before he passed away, Scholte taught a Swedish cutter named Peter Gustav Anderson, then co-founded Anderson & Sheppard in 1906. Anderson & Sheppard dressed some of the most stylish men of the 20th cent: Fred Astaire, Gary Cooper, and Noël Coward among them.

During this time, bespoke tailoring was a hush hush gentlemen's business and tailors frowned upon promotion. Even in this world, A&S was stricter than most. Older clients recall how they felt tailors peered down on them from the stacks of tweed

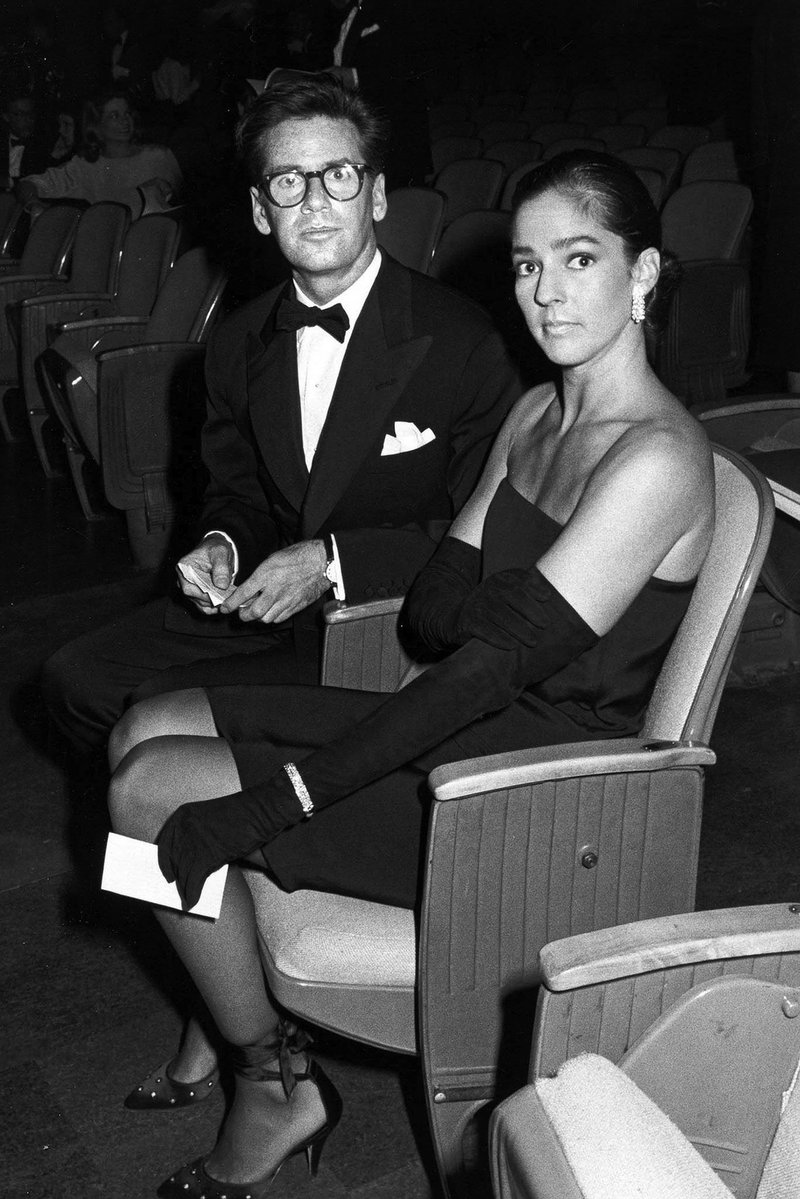

1960s A&S suit + Colin Harvey:

1960s A&S suit + Colin Harvey:

In the forward of Anderson & Sheppard's vanity book A Style is Born, Graydon Carter — a longtime A&S client, along with Fran Lebowitz — recalls how his cutter wouldn't even take requests if he thought they were in bad taste! This was like the Soup Nazi of tailoring shops.

Of course, times change. The very fact that A&S released a vanity book shows they've changed their views on self-promotion. They also have a very nice ready-to-wear line, which isn't something bespoke tailors would have considered 70 years ago.

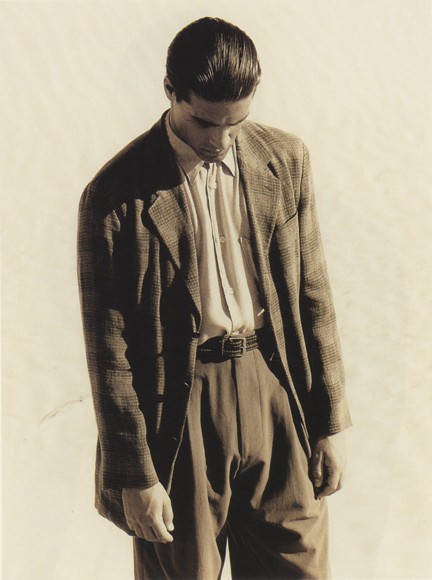

Brad Pitt here is wearing a bespoke suit, which means that the pattern was drafted from scratch and then the garment was perfected through a series of fittings. It retains the DNA of a drape cut (note the rounded chest), but has been clearly shaped by a stylist.

The most notable thing is the dropped buttoning point. The buttoning point is the top button on a two-button jacket, center button on a three-button jacket, or simply the button on a single-button jacket. On a classic coat, it's placed at the waist, the narrowest part of a torso

By dropping the buttoning point, you give the jacket a lower center of gravity. Armani did this a lot in his ready-to-wear tailoring. The overall effect was slouchy and louche, an attitude embodied in Richard Gere's role for American Gigolo.

But also, when you drop the buttoning point, you have to elongate the jacket. Otherwise, the distance between the button and hem will be too short. It appears Cortina wanted to balance this slouchy look with slightly longer jacket sleeves and trousers with a full break.

I think Pitt's suit is interesting for three reasons.

First, it's another sign that the age of skinny, short suits is coming to an end. Originally ushered into menswear in the early 2000s by Hedi Slimane and Thom Browne, it has a long run. But people want volume now.

First, it's another sign that the age of skinny, short suits is coming to an end. Originally ushered into menswear in the early 2000s by Hedi Slimane and Thom Browne, it has a long run. But people want volume now.

Second, it's interesting to see someone take a traditional tailoring technique (drape cut) and put it into this context. Even Armani wasn't really a drape cut. This is proper English drape.

Third, it shows how the bespoke tailoring industry has changed.

Third, it shows how the bespoke tailoring industry has changed.

100 years ago, Scholte sneered at entertainers and wouldn't even take style requests from clients. 50 years ago, Anderson & Sheppard's managers looked down on the idea of advertising. But now they regularly do things with stars, stylists, and fashion houses like Wales Bonner.

I don't say this with any degree of snobbery. Today's tailoring world might look very different to a cutter or tailor from 100 years ago. But I'm glad that open minded people do what they need to introduce people to tailoring and, most importantly, keep this craft alive.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh