COATUE East Meet West Deck

102 Pages on Public Markets every investor should read

My highlights 🧵

1/ Tech Trends - higher returns & volatility

2/ Change in Stock Leadership - hard to stay on top

...

10/ The AI Flywheel

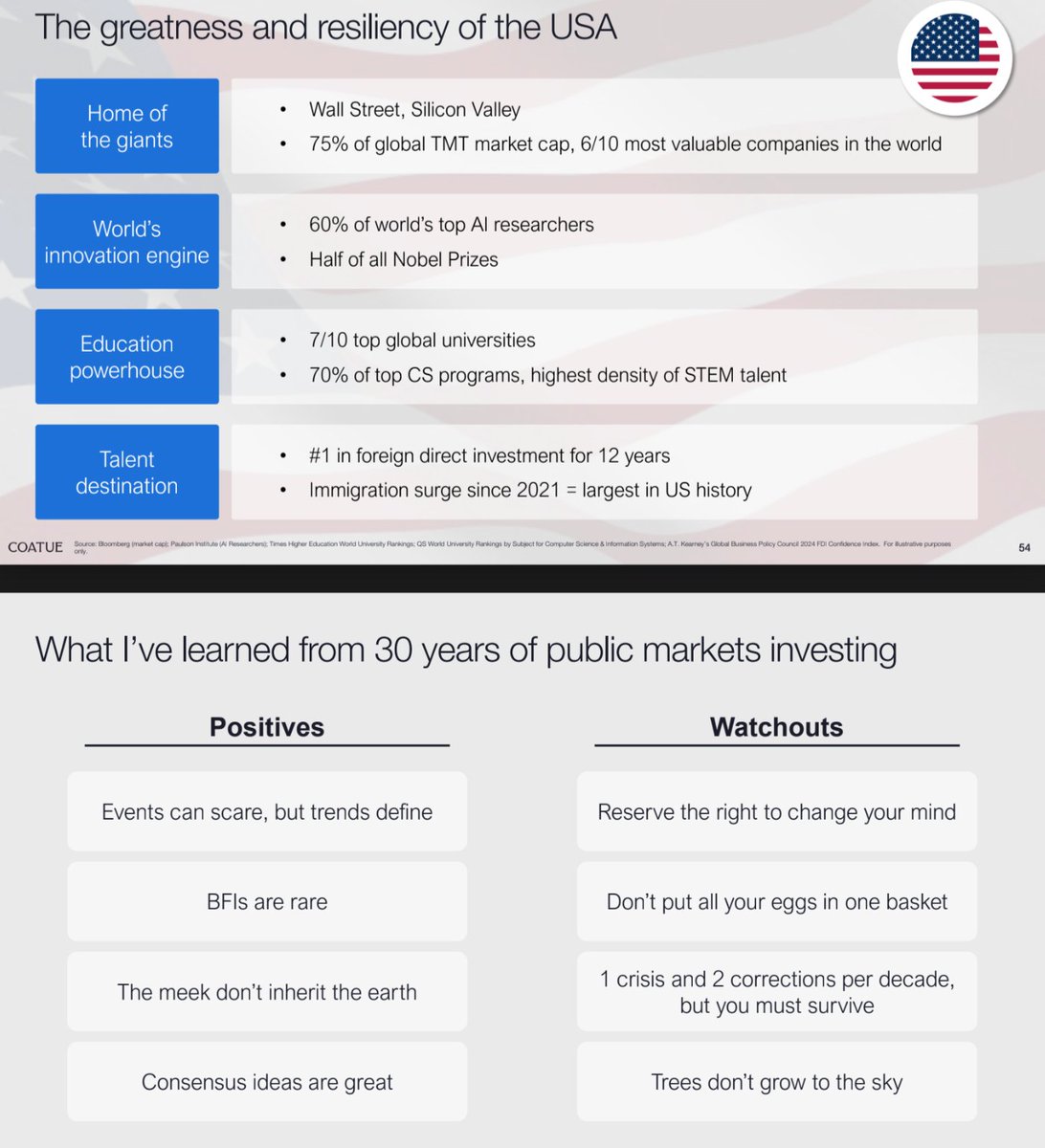

11/ Long the $USA

102 Pages on Public Markets every investor should read

My highlights 🧵

1/ Tech Trends - higher returns & volatility

2/ Change in Stock Leadership - hard to stay on top

...

10/ The AI Flywheel

11/ Long the $USA

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh