OECD does some of the best data work on China & industrial policy.

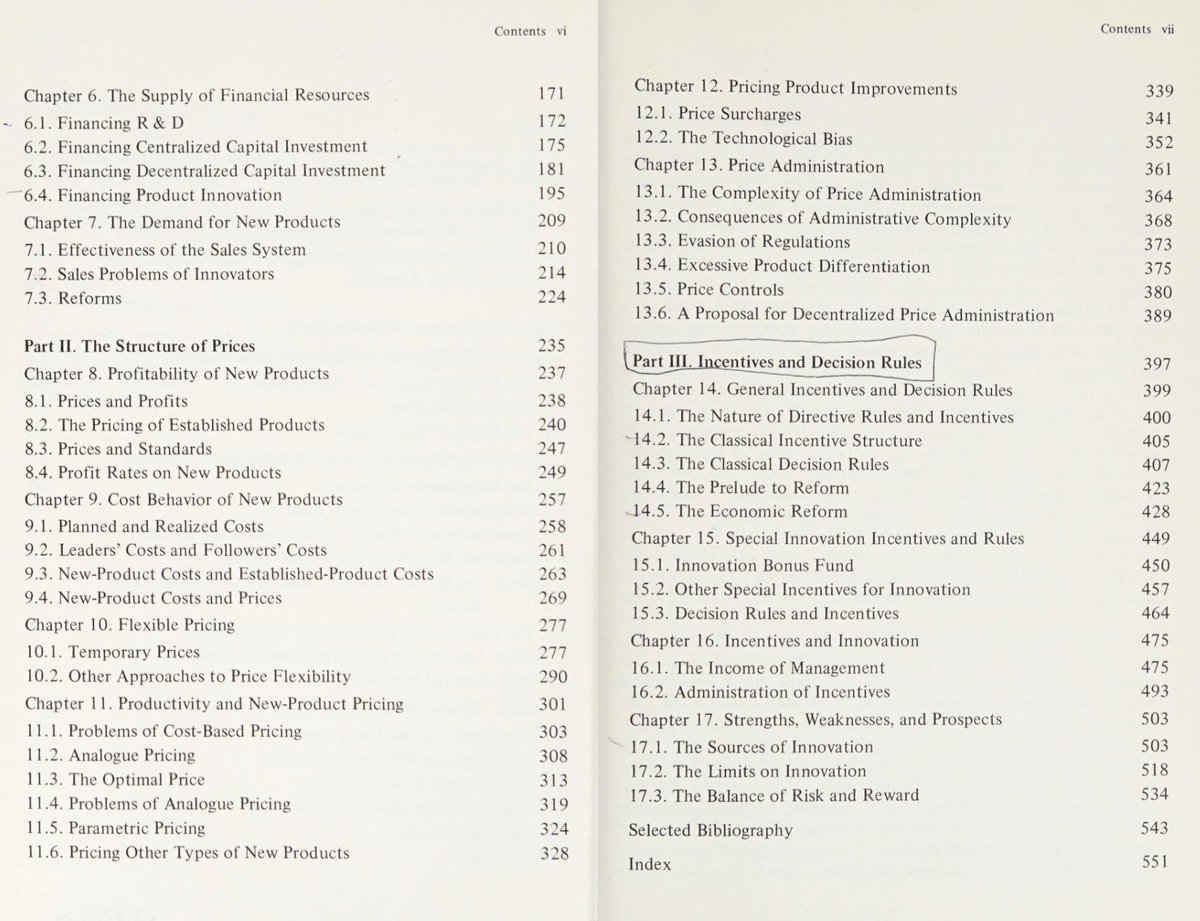

Here they look at 14 manufacturing industries and 482 top firms—⅔ global output, ½ in OECD and ⅓ in China.

In nearly all industries, Chinese firms invest more, are more productive, but earn less profit.

Here they look at 14 manufacturing industries and 482 top firms—⅔ global output, ½ in OECD and ⅓ in China.

In nearly all industries, Chinese firms invest more, are more productive, but earn less profit.

They've developed a very cool database—the OECD MAnufacturing Groups and Industrial Corporations (MAGIC) database—that they draw on to do this, and have written several other reports comparing industrial policies and subsidies across countries.

In other recent work they look at semiconductor subsidies across the globe.

Firms in China receive far higher subsidies as a percent of revenue ~10%.

They also derive much more of their revenue domestically (~50%) and hold far more of their assets domestically (~90%).

Firms in China receive far higher subsidies as a percent of revenue ~10%.

They also derive much more of their revenue domestically (~50%) and hold far more of their assets domestically (~90%).

Reports

The market implications of industrial subsidies (May 2025): one.oecd.org/document/TAD/T…

Recent trends in semiconductor subsidies (April 2025): oecd.org/content/dam/oe…

How Governments Back the Largest Manufacturing Firms: Insights from OECD MAGIC: oecd.org/content/dam/oe…

The market implications of industrial subsidies (May 2025): one.oecd.org/document/TAD/T…

Recent trends in semiconductor subsidies (April 2025): oecd.org/content/dam/oe…

How Governments Back the Largest Manufacturing Firms: Insights from OECD MAGIC: oecd.org/content/dam/oe…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh