1. Megalithic Croatia – Day 3 🧵

Split. The basement of Diocletian’s Palace.

💥💥💥BREAKTHROUGH! 💥💥💥

💥💥OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENT💥💥

We’ll remember June 4th, 2025, as the day I discovered the first man-made, cast ancient limestone block!

This will be the most important thread you’ll read all year — and it’s only July. I’m not kidding.

So where’s that stone?

Split. The basement of Diocletian’s Palace.

💥💥💥BREAKTHROUGH! 💥💥💥

💥💥OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENT💥💥

We’ll remember June 4th, 2025, as the day I discovered the first man-made, cast ancient limestone block!

This will be the most important thread you’ll read all year — and it’s only July. I’m not kidding.

So where’s that stone?

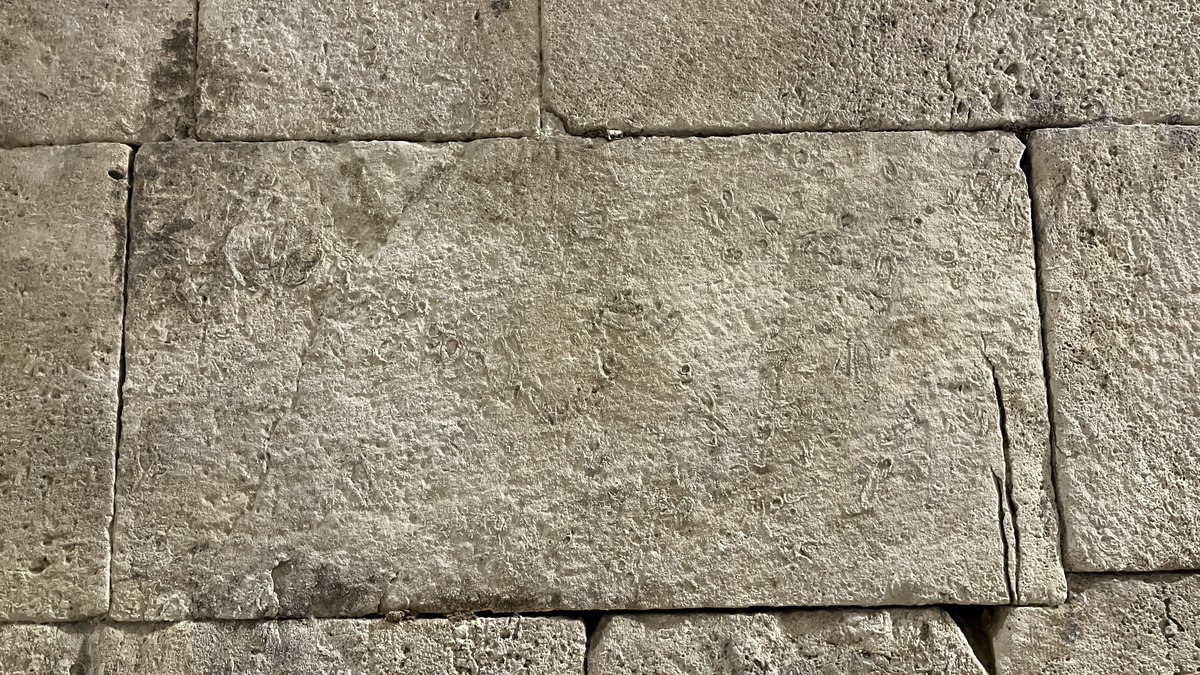

2. It’s a limestone block in the basement of Diocletian’s Palace in Split — specifically, a lintel. This will be hugely significant later on.

A limestone block — and it’s got MUD CRAKC patterns.

What? 😱

Cracks formed from shrinkage during drying.

Wait, what? Drying? Shrinking? A limestone block? That’s IMPOSSIBLE.

Yeees! That’s the point!

A limestone block — and it’s got MUD CRAKC patterns.

What? 😱

Cracks formed from shrinkage during drying.

Wait, what? Drying? Shrinking? A limestone block? That’s IMPOSSIBLE.

Yeees! That’s the point!

3. Exactly — natural limestone doesn’t behave like that.

It doesn’t soak up water like a sponge, doesn’t soften and doesn’t shrink.

That’s why it’s perfect for building cisterns and water reservoirs without needing any kind of lining.

Medieval cathedrals and ancient cisterns don’t shrink.

Limestone is waterproof. Full stop.

It doesn’t soak up water like a sponge, doesn’t soften and doesn’t shrink.

That’s why it’s perfect for building cisterns and water reservoirs without needing any kind of lining.

Medieval cathedrals and ancient cisterns don’t shrink.

Limestone is waterproof. Full stop.

4. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that this stone was found with those cracks already in it and someone just carved it into a lintel anyway.

Now look at it from underneath. There’s no way anyone would deliberately build a lintel out of a stone in that condition.

Mathematically? That’s a zero percent chance.

If this were just any other stone in the wall, I’d shrug and say, “Eh, whatever, maybe they threw it in.” But for a lintel? No f way.

Now look at it from underneath. There’s no way anyone would deliberately build a lintel out of a stone in that condition.

Mathematically? That’s a zero percent chance.

If this were just any other stone in the wall, I’d shrug and say, “Eh, whatever, maybe they threw it in.” But for a lintel? No f way.

5. And yet, there it is.

If it wasn’t installed broken (because they weren’t idiots), then the only remaining option is: it cracked after it was placed.

Which brings us right back to the artificial limestone theory — because natural limestone just doesn’t crack like that.

The circle is complete — and it just snapped shut on every naysayer’s nonsense.

Lo-gic!

Oh, one last classic naysayer line: “Maybe it’s a modern restoration job.”

Well, first of all, it’s a pretty bad one if it is. Second — even then we’re back to square one: mud cracks. That restorer would’ve needed the recipe for artificial limestone.

So even in that case — it’s still artificial limestone. Just maybe not 2,000 years old — maybe 50.

If it wasn’t installed broken (because they weren’t idiots), then the only remaining option is: it cracked after it was placed.

Which brings us right back to the artificial limestone theory — because natural limestone just doesn’t crack like that.

The circle is complete — and it just snapped shut on every naysayer’s nonsense.

Lo-gic!

Oh, one last classic naysayer line: “Maybe it’s a modern restoration job.”

Well, first of all, it’s a pretty bad one if it is. Second — even then we’re back to square one: mud cracks. That restorer would’ve needed the recipe for artificial limestone.

So even in that case — it’s still artificial limestone. Just maybe not 2,000 years old — maybe 50.

6. The bottom-view photo also answers the question: could it just be a cracked surface layer on top?

Nope. There’s no extra layer — the block sits flush with the ones beneath it.

(And by the way, yes, the one next to it is also cast — for the same exact reasons.)

Nope. There’s no extra layer — the block sits flush with the ones beneath it.

(And by the way, yes, the one next to it is also cast — for the same exact reasons.)

7. It’s important to note: I’d already decided this was cast, not carved before I even pulled the secret weapon — my XRF analyzer — from my backpack.

I got there using basic logic. You know, thinking. Not chemistry.

The XRF is just the cherry on top. This lintel is cast limestone, period. If the XRF agrees — great, bonus points. But it’s not essential.

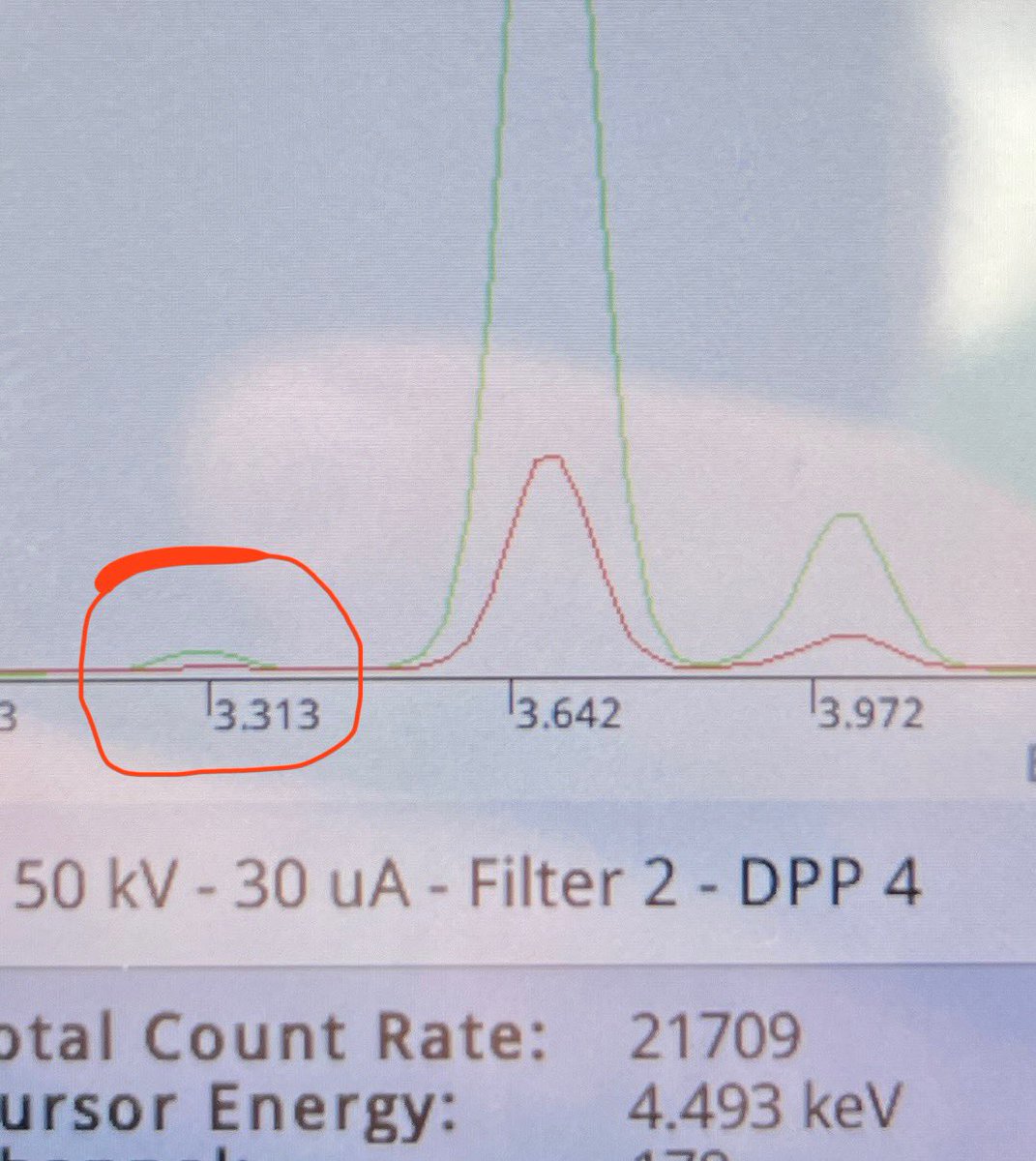

Here’s the XRF spectrum of that lintel: that peak at 3.31 keV? That’s the potassium alpha X-ray signal.

This rock contains potassium. Full stop.

Naysayers, you are free to go there to repeat my measurement. You’ll end up with the same result of course.

I got there using basic logic. You know, thinking. Not chemistry.

The XRF is just the cherry on top. This lintel is cast limestone, period. If the XRF agrees — great, bonus points. But it’s not essential.

Here’s the XRF spectrum of that lintel: that peak at 3.31 keV? That’s the potassium alpha X-ray signal.

This rock contains potassium. Full stop.

Naysayers, you are free to go there to repeat my measurement. You’ll end up with the same result of course.

8. Now show me a limestone quarry where you can mine potassium-rich limestone. I’ll wait…

So where was this stone quarried? NOWHERE.

Oh.

And how much potassium does natural limestone normally have? Basically zero.

There’s no potassium in natural limestone. (Close to) zero.

Why?

Because of how elements dissolve in nature. Potassium (and sodium too, by the way) is super water-soluble.

So instead of settling into the forming limestone, it just dissolves and washes away — even from dead plants and animals.

So this potassium? It was put there by humans. No way around it.

So where was this stone quarried? NOWHERE.

Oh.

And how much potassium does natural limestone normally have? Basically zero.

There’s no potassium in natural limestone. (Close to) zero.

Why?

Because of how elements dissolve in nature. Potassium (and sodium too, by the way) is super water-soluble.

So instead of settling into the forming limestone, it just dissolves and washes away — even from dead plants and animals.

So this potassium? It was put there by humans. No way around it.

9. Wait! Couldn’t it just be coated with some potassium-based substance that I just happened to measure?

That’s the question I wasted (unnecessarily) two days on — until my dumb brain finally remembered: “mud cracks.”

Who cares if UNESCO forbids potassium-based restoration techniques — and they definitely didn’t smear it on — if there are mud cracks?

And who cares if Vicko Andrić, the local mason who started the excavations in the 19th century, might’ve coated it? Again: mud cracks.

This stone got wet, then dried — and cracked. The potassium is just 🍒 on the cake. Extra evidence. If you’re a naysayer, ignore it — and it’s still artificial stone!

That’s the question I wasted (unnecessarily) two days on — until my dumb brain finally remembered: “mud cracks.”

Who cares if UNESCO forbids potassium-based restoration techniques — and they definitely didn’t smear it on — if there are mud cracks?

And who cares if Vicko Andrić, the local mason who started the excavations in the 19th century, might’ve coated it? Again: mud cracks.

This stone got wet, then dried — and cracked. The potassium is just 🍒 on the cake. Extra evidence. If you’re a naysayer, ignore it — and it’s still artificial stone!

10. For those who missed the experiment — here’s the potassium-rich cast stone I made in my backyard, behind my car, using wood ash extract.

No idea if it’ll hold up — that’s the whole point of the test.

Thankfully, geopolymers tend to get stronger over time. So there’s hope.

No idea if it’ll hold up — that’s the whole point of the test.

Thankfully, geopolymers tend to get stronger over time. So there’s hope.

11. Back to the basement.

Since I was there, I started waving the XRF around at other stones.

Tried looking for more potassium-bearing blocks by hunting for random cracks.

But then I realized that’s stupid — they couldn’t have screwed up every cast stone. Surely some of them came out just fine. Looking for cracks is dumb.

So how do you spot artificial stones?

Took me a while, but I finally got it.

Simple as this:

If it’s carved, it’s not cast.

And vice versa:

If it’s cast, it’s not carved.

🤣

Your turn now — make a guess!

Since I was there, I started waving the XRF around at other stones.

Tried looking for more potassium-bearing blocks by hunting for random cracks.

But then I realized that’s stupid — they couldn’t have screwed up every cast stone. Surely some of them came out just fine. Looking for cracks is dumb.

So how do you spot artificial stones?

Took me a while, but I finally got it.

Simple as this:

If it’s carved, it’s not cast.

And vice versa:

If it’s cast, it’s not carved.

🤣

Your turn now — make a guess!

12. Take a good look at this stone in the wall not far from that lintel. Based on simple visual observation, would you say it’s natural or cast?

Good job — it’s carved. The chisel marks are obvious.

It’s natural limestone, so naturally there’s no potassium in that one. And yes, I checked it with the XRF tool too.

Good job — it’s carved. The chisel marks are obvious.

It’s natural limestone, so naturally there’s no potassium in that one. And yes, I checked it with the XRF tool too.

13. And this one? What do you think?

Correct!

No chisel marks — so it wasn’t carved. If there’s potassium, it’s definitely cast.

So? I scanned it — and yep, there is!

That’s it — you’ve graduated. You’re now a certified artificial limestone expert. Congrats!

Correct!

No chisel marks — so it wasn’t carved. If there’s potassium, it’s definitely cast.

So? I scanned it — and yep, there is!

That’s it — you’ve graduated. You’re now a certified artificial limestone expert. Congrats!

14. The two types of stones — natural and artificial — are all mixed together in this wall.

Check out this quick video showing the two stones from earlier — they’re about a meter apart.

I didn’t have time to figure out the pattern of how they’re distributed — had to leave.

Check out this quick video showing the two stones from earlier — they’re about a meter apart.

I didn’t have time to figure out the pattern of how they’re distributed — had to leave.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh