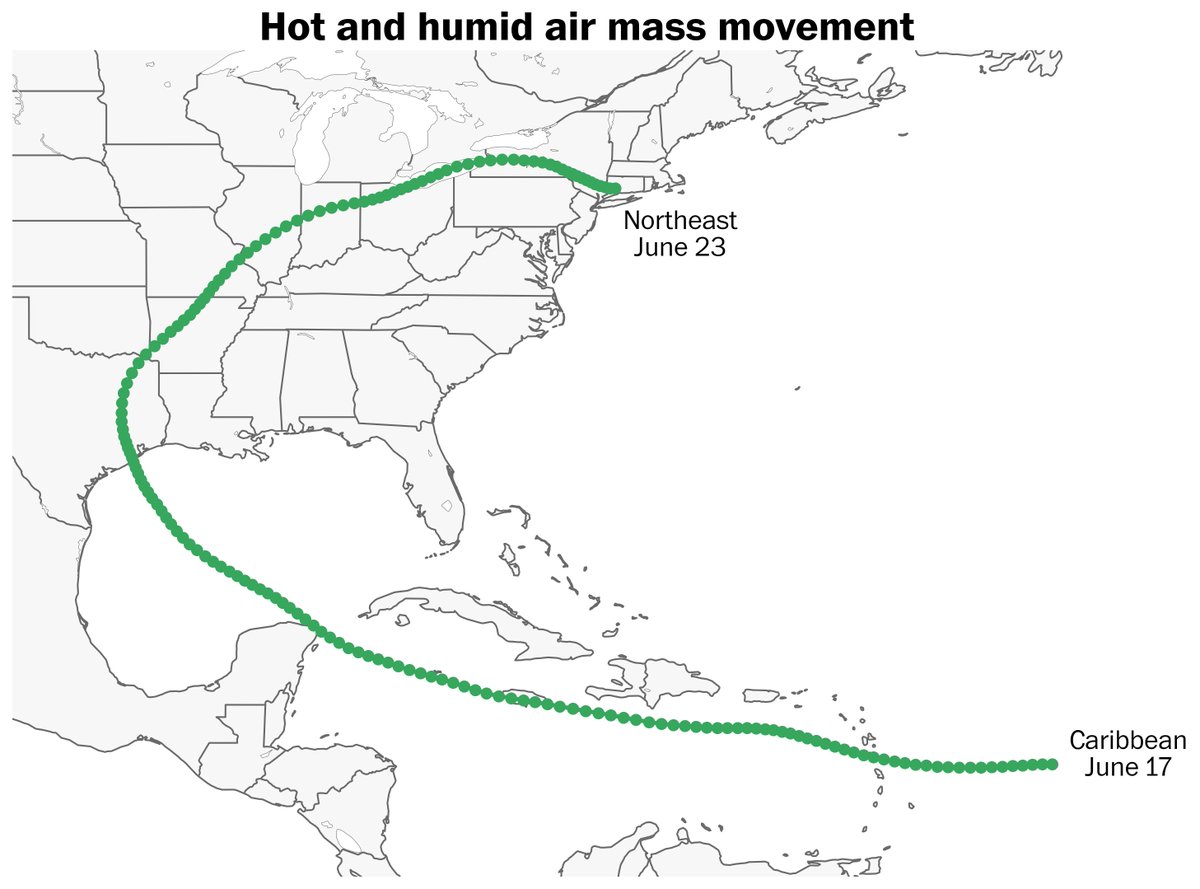

There have been varying meteorological forces behind recent extreme rainfall events, but they are all connected by very unusual amounts of moisture pulsing above the United States.

Precipitable water, a measure of the total amount of water in the atmosphere, has been above the 90th percentile on half of all days so far this summer — the largest number of days to-date since records began in 1940. It's been above-average on all but five days.

Forecasters use precipitable water to gauge how much fuel is available for storms and how much rain can possibly fall. While it's not a one-to-one relationship, higher precipitable water brings a higher the chance for extreme rainfall — as long as there's a mechanism to squeeze the moisture out of the sky.

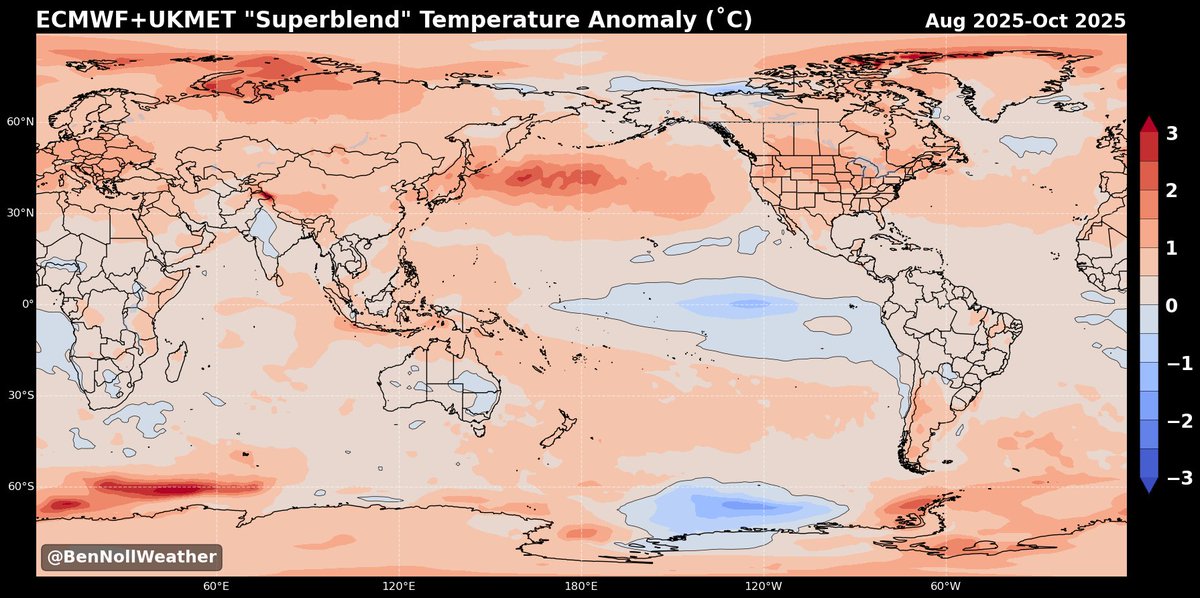

Globally, precipitable water reached record levels in 2024. So far, 2025 is a few notches below last year's record pace, but corridors of unusually high atmospheric moisture have developed near areas of much warmer than average oceans. This includes the central and eastern United States, Europe and eastern Asia.

Part of a meteorologist's job is to be an atmospheric detective — to understand and help others understand why certain things are happening.

Yes, it rains hard and sometimes floods during summer, but to understand what's driving this season's excessive rainfall is critically important. To dismiss it as 'just weather' is selling it short.

I think there's plenty of evidence to suggest that the trend toward a moister atmosphere is leaving an imprint on weather patterns in the United States this summer.

Precipitable water, a measure of the total amount of water in the atmosphere, has been above the 90th percentile on half of all days so far this summer — the largest number of days to-date since records began in 1940. It's been above-average on all but five days.

Forecasters use precipitable water to gauge how much fuel is available for storms and how much rain can possibly fall. While it's not a one-to-one relationship, higher precipitable water brings a higher the chance for extreme rainfall — as long as there's a mechanism to squeeze the moisture out of the sky.

Globally, precipitable water reached record levels in 2024. So far, 2025 is a few notches below last year's record pace, but corridors of unusually high atmospheric moisture have developed near areas of much warmer than average oceans. This includes the central and eastern United States, Europe and eastern Asia.

Part of a meteorologist's job is to be an atmospheric detective — to understand and help others understand why certain things are happening.

Yes, it rains hard and sometimes floods during summer, but to understand what's driving this season's excessive rainfall is critically important. To dismiss it as 'just weather' is selling it short.

I think there's plenty of evidence to suggest that the trend toward a moister atmosphere is leaving an imprint on weather patterns in the United States this summer.

Corridors of unusually high atmospheric moisture have developed near areas of much warmer than average oceans — which happen to be located near densely populated parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

Dr Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research who has been publishing on the topic of increasing water vapor since the 1990s, said that the pattern has been "too often ignored" with rising temperatures getting more attention.

In today's @washingtonpost: This is why there’s been so much extreme rainfall and flooding in the U.S.

Gift link 🎁

wapo.st/4lWVYpE

Gift link 🎁

wapo.st/4lWVYpE

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh