Introduction to the CAPTOR Radar

1/25 The CAPTOR radar is the beating heart of the Eurofighter Typhoon’s sensor suite, enabling its air superiority and multi-role capabilities. Developed through a multinational effort, it has evolved from a Cold War-era concept to a cutting-edge system. This thread traces its journey from requirement to operational use, its technology, variants, and relevance today, with a focus on the UK’s investment in the ECRS Mk2. As always views are my own and posts can be corrected if errors are found. This is third in series of UK airborne radars (Blue Fox/Vixen, Fox Hunter and now CAPTOR). Larger radars will be covered soon (Search Water etc).

1/25 The CAPTOR radar is the beating heart of the Eurofighter Typhoon’s sensor suite, enabling its air superiority and multi-role capabilities. Developed through a multinational effort, it has evolved from a Cold War-era concept to a cutting-edge system. This thread traces its journey from requirement to operational use, its technology, variants, and relevance today, with a focus on the UK’s investment in the ECRS Mk2. As always views are my own and posts can be corrected if errors are found. This is third in series of UK airborne radars (Blue Fox/Vixen, Fox Hunter and now CAPTOR). Larger radars will be covered soon (Search Water etc).

Origins of the CAPTOR Radar

2/25 The CAPTOR, originally the ECR-90, was born in the 1980s under the Future European Fighter Aircraft (FEFA) programme, aimed at countering Soviet aircraft like the MiG-29. Led by the EuroRadar consortium (UK, Germany, Italy, Spain), it built on the Ferranti Blue Vixen radar from the Sea Harrier FA2, leveraging pulse Doppler technology for superior target detection in cluttered environments.

2/25 The CAPTOR, originally the ECR-90, was born in the 1980s under the Future European Fighter Aircraft (FEFA) programme, aimed at countering Soviet aircraft like the MiG-29. Led by the EuroRadar consortium (UK, Germany, Italy, Spain), it built on the Ferranti Blue Vixen radar from the Sea Harrier FA2, leveraging pulse Doppler technology for superior target detection in cluttered environments.

Heritage and Technological Roots

3/25 The CAPTOR’s heritage lies in Cold War radar advancements, particularly pulse Doppler systems used in the Tornado’s Foxhunter radar. These provided robust electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM) against Soviet jamming. Collaborative expertise from GEC-Marconi (UK), DASA (Germany), FIAR (Italy), and INISEL (Spain) shaped a radar that balanced performance, cost, and NATO interoperability.

3/25 The CAPTOR’s heritage lies in Cold War radar advancements, particularly pulse Doppler systems used in the Tornado’s Foxhunter radar. These provided robust electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM) against Soviet jamming. Collaborative expertise from GEC-Marconi (UK), DASA (Germany), FIAR (Italy), and INISEL (Spain) shaped a radar that balanced performance, cost, and NATO interoperability.

Initial User Requirements

4/25 In the mid-1980s, the CAPTOR’s requirements focused on air superiority: long-range detection, tracking multiple targets, and engaging beyond-visual-range (BVR) with missiles like the AIM-120 AMRAAM. Operating in the I/J-band (8-12 GHz), it needed to excel in high-threat environments. The radar’s software, written in Ada, was designed for future upgrades to meet evolving needs.

4/25 In the mid-1980s, the CAPTOR’s requirements focused on air superiority: long-range detection, tracking multiple targets, and engaging beyond-visual-range (BVR) with missiles like the AIM-120 AMRAAM. Operating in the I/J-band (8-12 GHz), it needed to excel in high-threat environments. The radar’s software, written in Ada, was designed for future upgrades to meet evolving needs.

Evolving Needs with the Typhoon

5/25 The end of the Cold War shifted the Typhoon’s role to multi-role operations, requiring the CAPTOR to add air-to-ground modes like synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and ground moving target indication (GMTI). User feedback from RAF Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) missions emphasised reliability, maintenance ease, and integration with NATO systems like Link 16.

5/25 The end of the Cold War shifted the Typhoon’s role to multi-role operations, requiring the CAPTOR to add air-to-ground modes like synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and ground moving target indication (GMTI). User feedback from RAF Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) missions emphasised reliability, maintenance ease, and integration with NATO systems like Link 16.

Development Milestones

6/25 Development began in 1989 with a $394.2 million contract. The ECR-90A prototype was tested in 1993 on a BAC-111 aircraft, followed by the ECR-90B and C models, with the latter integrated into the German DA5 Typhoon prototype in 1997. Named CAPTOR in 2000, the first production unit was delivered in March 2001, marking a key milestone.

6/25 Development began in 1989 with a $394.2 million contract. The ECR-90A prototype was tested in 1993 on a BAC-111 aircraft, followed by the ECR-90B and C models, with the latter integrated into the German DA5 Typhoon prototype in 1997. Named CAPTOR in 2000, the first production unit was delivered in March 2001, marking a key milestone.

Production and Build

7/25 Production of the CAPTOR-M, the mechanically scanned variant, started in 1998, led by Leonardo’s Edinburgh site (formerly Selex ES). Weighing 193 kg with liquid and air cooling, it featured three processing channels for search, tracking, and ECCM. Over 10,000 jobs were supported across the EuroRadar consortium’s supply chain, delivering radars for 630 Typhoons.

7/25 Production of the CAPTOR-M, the mechanically scanned variant, started in 1998, led by Leonardo’s Edinburgh site (formerly Selex ES). Weighing 193 kg with liquid and air cooling, it featured three processing channels for search, tracking, and ECCM. Over 10,000 jobs were supported across the EuroRadar consortium’s supply chain, delivering radars for 630 Typhoons.

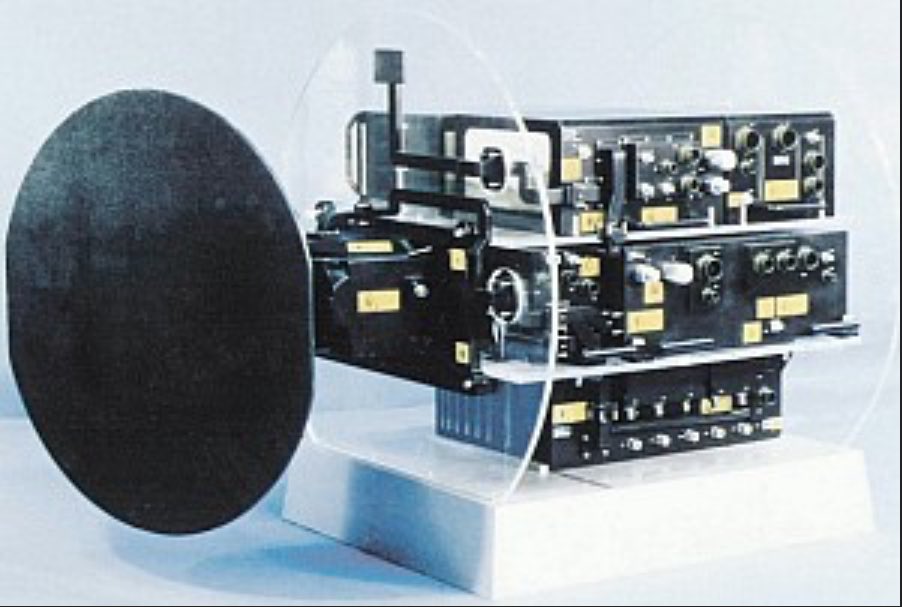

CAPTOR-M: The Original Variant

8/25 The CAPTOR-M, used in Tranche 1 and early Tranche 2 Typhoons, is a multi-mode pulse Doppler radar optimised for air-to-air combat. It supports BVR engagements and robust ECCM but has limited air-to-ground capabilities compared to later variants. Its self-diagnostic system allows rapid fault detection, minimising downtime.

8/25 The CAPTOR-M, used in Tranche 1 and early Tranche 2 Typhoons, is a multi-mode pulse Doppler radar optimised for air-to-air combat. It supports BVR engagements and robust ECCM but has limited air-to-ground capabilities compared to later variants. Its self-diagnostic system allows rapid fault detection, minimising downtime.

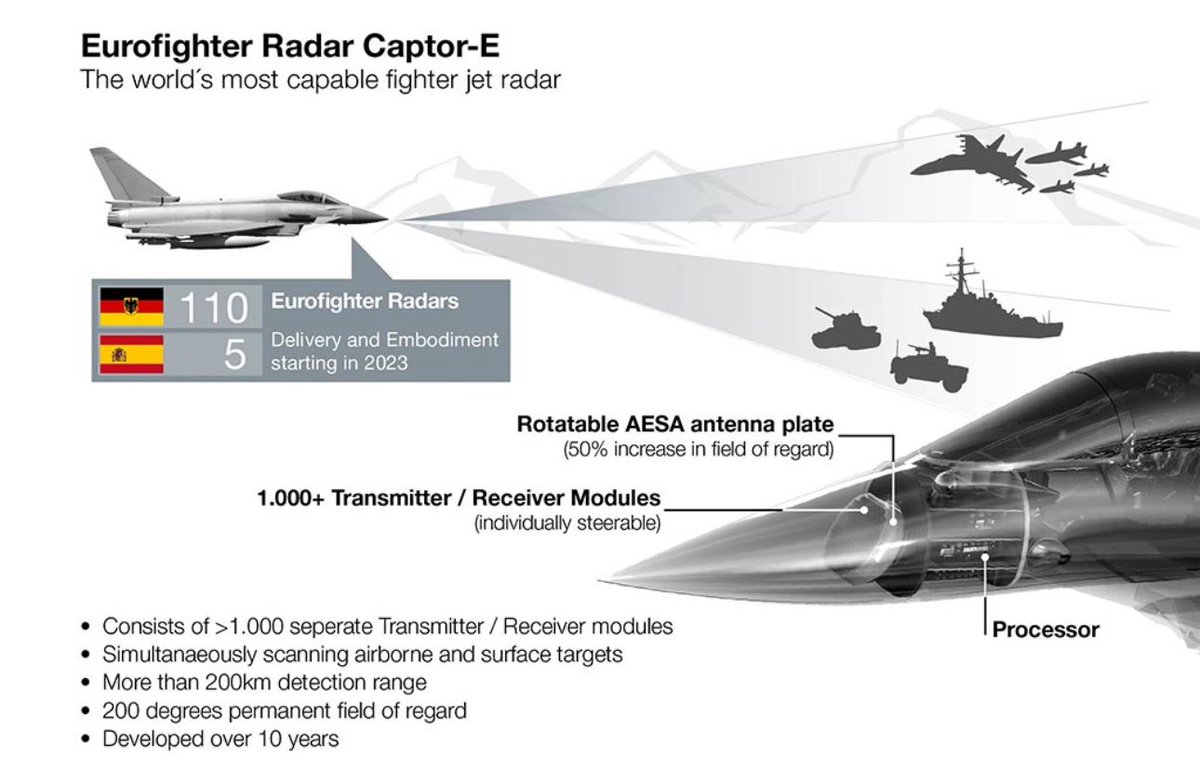

CAPTOR-E (ECRS Mk0)

9/25 The CAPTOR-E, or ECRS Mk0 (Radar One Plus), introduced active electronically scanned array (AESA) technology for Kuwait and Qatar. Using gallium arsenide (GaAs) high-power amplifiers, it offers improved range, accuracy, and jamming resistance. First delivered in 2019, it enhances multi-role performance for export customers.

9/25 The CAPTOR-E, or ECRS Mk0 (Radar One Plus), introduced active electronically scanned array (AESA) technology for Kuwait and Qatar. Using gallium arsenide (GaAs) high-power amplifiers, it offers improved range, accuracy, and jamming resistance. First delivered in 2019, it enhances multi-role performance for export customers.

ECRS Mk1 for Germany and Spain

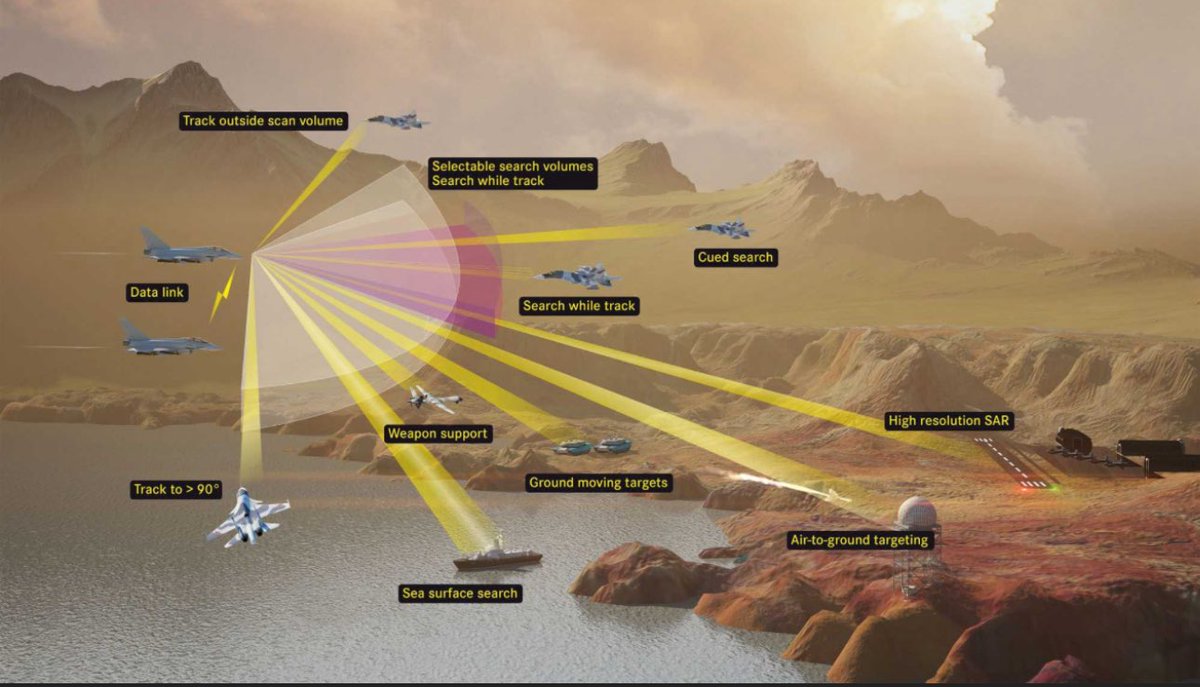

10/25 The ECRS Mk1, developed by Hensoldt and Indra, is tailored for Germany’s Quadriga and Spain’s Halcon programmes. Featuring a multi-channel digital receiver and broadband transmit-receive modules (TRMs), it excels in air-to-ground roles with ultra-high-resolution SAR and GMTI, plus electronic warfare functions. Deliveries are expected by the mid-2020s.

10/25 The ECRS Mk1, developed by Hensoldt and Indra, is tailored for Germany’s Quadriga and Spain’s Halcon programmes. Featuring a multi-channel digital receiver and broadband transmit-receive modules (TRMs), it excels in air-to-ground roles with ultra-high-resolution SAR and GMTI, plus electronic warfare functions. Deliveries are expected by the mid-2020s.

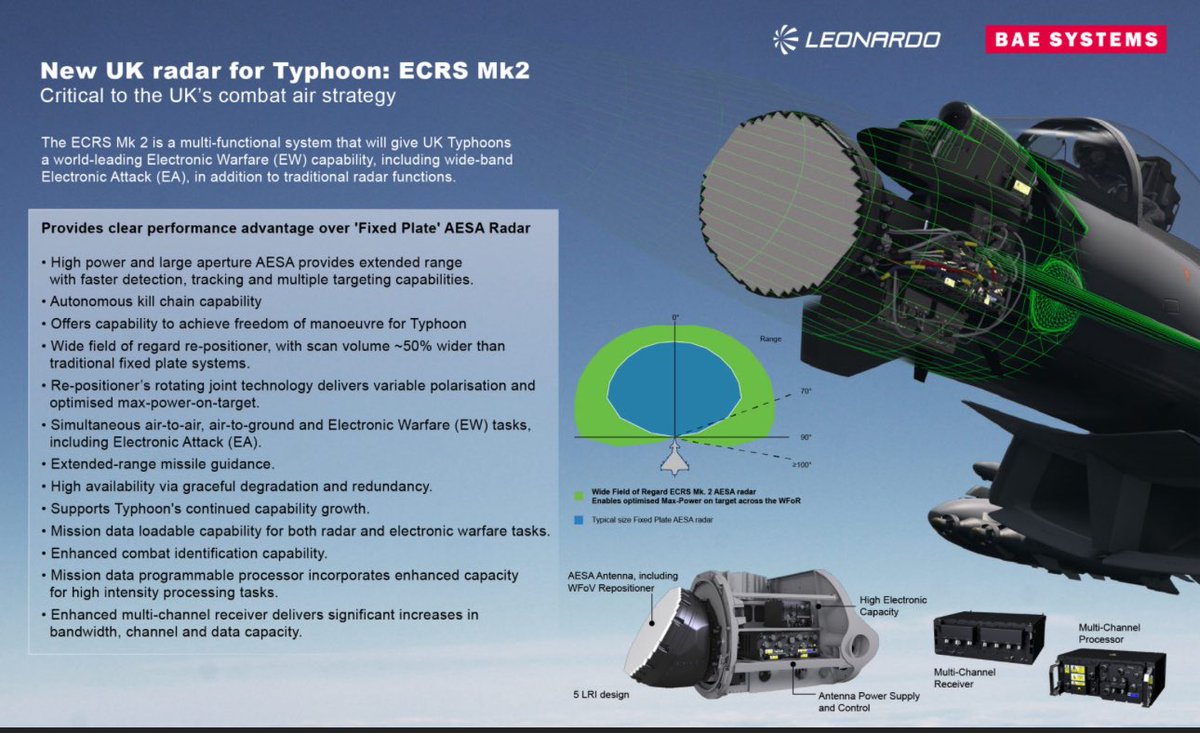

ECRS Mk2: The UK’s Advanced Leap

11/25 The ECRS Mk2, or Radar Two, is the RAF’s flagship radar, with a £2.35 billion investment for 40 sets. Featuring both GaAs and gallium nitride (GaN) amplifiers, it includes a swashplate repositioner (derived from the Selex ES-05 Raven) for a 50% wider field of regard. It integrates electronic warfare (EW) and attack (EA) capabilities, with first flight in September 2024.

11/25 The ECRS Mk2, or Radar Two, is the RAF’s flagship radar, with a £2.35 billion investment for 40 sets. Featuring both GaAs and gallium nitride (GaN) amplifiers, it includes a swashplate repositioner (derived from the Selex ES-05 Raven) for a 50% wider field of regard. It integrates electronic warfare (EW) and attack (EA) capabilities, with first flight in September 2024.

CAPTOR’s Core Technology

12/25 The CAPTOR-M uses a mechanically scanned antenna in the I/J-band, with three channels for simultaneous search, tracking, and ECCM. Its AESA variants (ECRS Mk0, Mk1, Mk2) use over 1,000 TRMs for near-instantaneous beam steering, improving range and jamming resistance. The ECRS Mk2’s GaN technology enhances power efficiency.

12/25 The CAPTOR-M uses a mechanically scanned antenna in the I/J-band, with three channels for simultaneous search, tracking, and ECCM. Its AESA variants (ECRS Mk0, Mk1, Mk2) use over 1,000 TRMs for near-instantaneous beam steering, improving range and jamming resistance. The ECRS Mk2’s GaN technology enhances power efficiency.

Technological Limitations

13/25 The CAPTOR-M’s mechanical scanning is slower than AESA systems, limiting its multi-domain performance. Early ECRS variants lack advanced AI for target classification or photonic radar technology. While the ECRS Mk2 addresses many gaps, it still trails fifth-generation radars like the F-35’s AN/APG-81 in stealth detection (happy to discuss on this one).

13/25 The CAPTOR-M’s mechanical scanning is slower than AESA systems, limiting its multi-domain performance. Early ECRS variants lack advanced AI for target classification or photonic radar technology. While the ECRS Mk2 addresses many gaps, it still trails fifth-generation radars like the F-35’s AN/APG-81 in stealth detection (happy to discuss on this one).

Integration with Typhoon Systems

14/25 The CAPTOR integrates with the Typhoon’s Attack and Identification System (AIS), fusing data with the PIRATE IRST, Defensive Aids Sub-System (DASS), and Link 16. This reduces pilot workload via automatic mode selection. The radar supports weapons like Meteor, Paveway IV, and Storm Shadow for precise targeting.

14/25 The CAPTOR integrates with the Typhoon’s Attack and Identification System (AIS), fusing data with the PIRATE IRST, Defensive Aids Sub-System (DASS), and Link 16. This reduces pilot workload via automatic mode selection. The radar supports weapons like Meteor, Paveway IV, and Storm Shadow for precise targeting.

Role of the DASS and PIRATE

15/25 The DASS, with countermeasures, chaff, flares, and a towed decoy, enhances survivability against radar-guided threats. The PIRATE IRST provides passive detection, complementing the CAPTOR’s active radar in jammed or stealthy environments. Together, they create a robust sensor suite for the Typhoon.

15/25 The DASS, with countermeasures, chaff, flares, and a towed decoy, enhances survivability against radar-guided threats. The PIRATE IRST provides passive detection, complementing the CAPTOR’s active radar in jammed or stealthy environments. Together, they create a robust sensor suite for the Typhoon.

Aerodynamic and Power Integration

16/25 The Typhoon’s large nose accommodates the CAPTOR’s powerful antenna, offering superior range compared to smaller fighters like the Rafale. Liquid and air cooling ensure reliability during high-performance flight, while self-diagnostic systems (hopefully) simplify maintenance, critical for operational readiness.

16/25 The Typhoon’s large nose accommodates the CAPTOR’s powerful antenna, offering superior range compared to smaller fighters like the Rafale. Liquid and air cooling ensure reliability during high-performance flight, while self-diagnostic systems (hopefully) simplify maintenance, critical for operational readiness.

Operational Use Across Nations

17/25 The CAPTOR-M equips Typhoons in the UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, Austria, Saudi Arabia, and Oman for air policing and combat operations. The RAF has used it in Operation Ellamy (Libya, 2011) and Operation Shader (Iraq/Syria, 2015 onwards). The ECRS Mk0 serves Kuwait and Qatar for regional security.

17/25 The CAPTOR-M equips Typhoons in the UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, Austria, Saudi Arabia, and Oman for air policing and combat operations. The RAF has used it in Operation Ellamy (Libya, 2011) and Operation Shader (Iraq/Syria, 2015 onwards). The ECRS Mk0 serves Kuwait and Qatar for regional security.

ECRS Mk1 and Mk2 in Operations

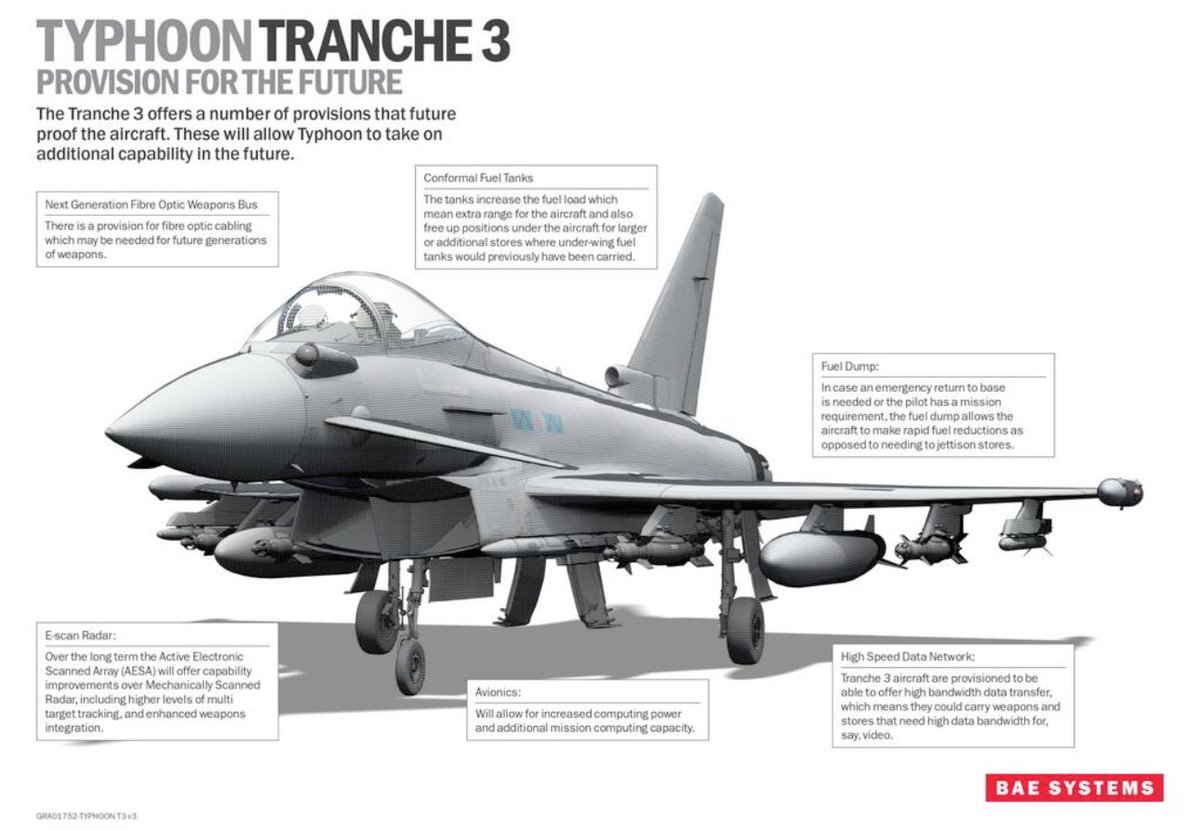

18/25 The ECRS Mk1 will enhance Germany and Spain’s Typhoons with advanced air-to-ground and EW capabilities. The ECRS Mk2, for the RAF’s Tranche 3 Typhoons, supports electronic attack and SEAD roles (RAF Typhoon just needs a SEAD weapon, absent since the retirement of ALARM), complementing F-35Bs in NATO operations. Its IOC is expected by 2030.

18/25 The ECRS Mk1 will enhance Germany and Spain’s Typhoons with advanced air-to-ground and EW capabilities. The ECRS Mk2, for the RAF’s Tranche 3 Typhoons, supports electronic attack and SEAD roles (RAF Typhoon just needs a SEAD weapon, absent since the retirement of ALARM), complementing F-35Bs in NATO operations. Its IOC is expected by 2030.

Strengths of the CAPTOR Radar (personal views)

19/25 The CAPTOR’s versatility, reliability, and upgradeability are key strengths. The CAPTOR-M excels in air superiority, while AESA variants like the ECRS Mk2 offer multi-role and EW/EA capabilities. The Mk2’s swashplate provides a wider field of regard, enhancing situational awareness.

19/25 The CAPTOR’s versatility, reliability, and upgradeability are key strengths. The CAPTOR-M excels in air superiority, while AESA variants like the ECRS Mk2 offer multi-role and EW/EA capabilities. The Mk2’s swashplate provides a wider field of regard, enhancing situational awareness.

Weaknesses of the CAPTOR Radar (personal views)

20/25 The CAPTOR-M’s mechanical scanning limits its speed and multi-domain performance. The £2.35 billion cost for 40 ECRS Mk2 sets has raised concerns, especially compared to the F-35’s AN/APG-81, already in production. Maintenance complexity and the absence of AI-driven features are also drawbacks.

A further question to the readers would be “more Typhoon or more ECRS Mk2 equipped Typhoon above the 40 (36 operational) ordered to date. I would further ask, dedicated SEAD weapon or SPEAR 3?

20/25 The CAPTOR-M’s mechanical scanning limits its speed and multi-domain performance. The £2.35 billion cost for 40 ECRS Mk2 sets has raised concerns, especially compared to the F-35’s AN/APG-81, already in production. Maintenance complexity and the absence of AI-driven features are also drawbacks.

A further question to the readers would be “more Typhoon or more ECRS Mk2 equipped Typhoon above the 40 (36 operational) ordered to date. I would further ask, dedicated SEAD weapon or SPEAR 3?

Comparison with Legacy Systems

21/25 Compared to the Tornado’s Foxhunter radar (100 km detection range for a 10 m² RCS target), the CAPTOR-M (135 km) offers superior range, resolution, and ECCM. Its sensor fusion and three-channel architecture far outstrip legacy systems, enabling effective air-to-air and air-to-ground roles.

21/25 Compared to the Tornado’s Foxhunter radar (100 km detection range for a 10 m² RCS target), the CAPTOR-M (135 km) offers superior range, resolution, and ECCM. Its sensor fusion and three-channel architecture far outstrip legacy systems, enabling effective air-to-air and air-to-ground roles.

Comparison with Peer Systems

22/25 Against peers like the Rafale’s RBE2 (initially mechanically scanned) and Su-27’s Slot Back (120 km range), the CAPTOR-M was competitive in the 2000s. The ECRS Mk0 and Mk1 match modern AESA radars like the F/A-18’s AN/APG-79, but the AN/APG-81 on the F-35 leads in stealth detection and data fusion (happy to be challenged).

22/25 Against peers like the Rafale’s RBE2 (initially mechanically scanned) and Su-27’s Slot Back (120 km range), the CAPTOR-M was competitive in the 2000s. The ECRS Mk0 and Mk1 match modern AESA radars like the F/A-18’s AN/APG-79, but the AN/APG-81 on the F-35 leads in stealth detection and data fusion (happy to be challenged).

The ECRS Mk2’s Unique Edge

23/25 The ECRS Mk2’s swashplate and EW/EA capabilities give it an edge over fixed AESA radars, enabling simultaneous tracking and jamming. Its £2.35 billion cost for 40 sets reflects its advanced GaN technology and integration with the Typhoon’s systems, positioning it as a critical asset for the RAF.

23/25 The ECRS Mk2’s swashplate and EW/EA capabilities give it an edge over fixed AESA radars, enabling simultaneous tracking and jamming. Its £2.35 billion cost for 40 sets reflects its advanced GaN technology and integration with the Typhoon’s systems, positioning it as a critical asset for the RAF.

Contemporary Relevance and Challenges

24/25 The CAPTOR-M remains effective for air policing, but its mechanical scanning is outdated. The ECRS Mk0 and Mk1 meet multi-role needs, but stealth and hypersonic threats demand the ECRS Mk2’s capabilities. Its high cost is debated, given the AN/APG-81’s maturity, yet its unique features justify the investment for NATO operations.

24/25 The CAPTOR-M remains effective for air policing, but its mechanical scanning is outdated. The ECRS Mk0 and Mk1 meet multi-role needs, but stealth and hypersonic threats demand the ECRS Mk2’s capabilities. Its high cost is debated, given the AN/APG-81’s maturity, yet its unique features justify the investment for NATO operations.

Conclusion: The Future with ECRS Mk2

25/25 The CAPTOR radar has evolved from a Cold War air superiority system to a multi-role powerhouse, with the ECRS Mk2 representing its pinnacle. The UK’s £2.35 billion investment in 40 sets underscores its strategic importance, offering unmatched EW/EA and a wide field of regard to complement F-35Bs. While expensive compared to the AN/APG-81, its tailored capabilities ensure the Typhoon’s relevance through 2060, supported by the Long-Term Evolution programme. The ECRS Mk2’s first flight in 2024 and IOC by 2030 mark a bold step, keeping the RAF at the forefront of air combat technology. The challenge for the RAF, is 36 enough?

25/25 The CAPTOR radar has evolved from a Cold War air superiority system to a multi-role powerhouse, with the ECRS Mk2 representing its pinnacle. The UK’s £2.35 billion investment in 40 sets underscores its strategic importance, offering unmatched EW/EA and a wide field of regard to complement F-35Bs. While expensive compared to the AN/APG-81, its tailored capabilities ensure the Typhoon’s relevance through 2060, supported by the Long-Term Evolution programme. The ECRS Mk2’s first flight in 2024 and IOC by 2030 mark a bold step, keeping the RAF at the forefront of air combat technology. The challenge for the RAF, is 36 enough?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh