What treatment strategies align best with the neurobiology of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD)?

A 2016 six-week RCT in treatment-seeking young adult males suggests bupropion may be more effective than escitalopram for IGD, particularly for impulsivity and attention deficits, though findings are limited to a controlled cohort.

Let’s examine the neurobiological implications and clinical relevance for managing reward dysregulation and executive dysfunction.

1/13🧵

A 2016 six-week RCT in treatment-seeking young adult males suggests bupropion may be more effective than escitalopram for IGD, particularly for impulsivity and attention deficits, though findings are limited to a controlled cohort.

Let’s examine the neurobiological implications and clinical relevance for managing reward dysregulation and executive dysfunction.

1/13🧵

The trial asked a targeted clinical question:

Can pharmacotherapy improve core IGD symptoms, especially in those with attentional and impulse control challenges?

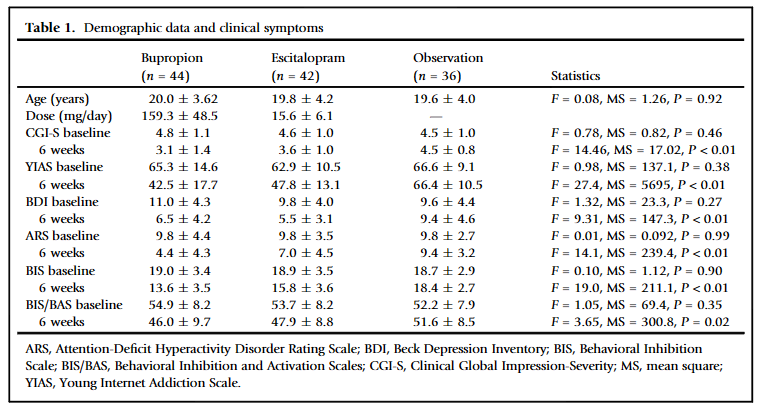

119 young males with IGD were randomised to:

● Bupropion SR (150–300 mg/day, n=44)

● Escitalopram (10–20 mg/day, n=42)

● Observation (n=33)

2/13🧵

Can pharmacotherapy improve core IGD symptoms, especially in those with attentional and impulse control challenges?

119 young males with IGD were randomised to:

● Bupropion SR (150–300 mg/day, n=44)

● Escitalopram (10–20 mg/day, n=42)

● Observation (n=33)

2/13🧵

Multiple symptom domains were tracked:

● YIAS: Internet gaming severity

● ARS: Attention deficits

● BIS/BAS: Impulsivity

● BDI: Depressive symptoms

● CGI-S: Global clinical severity

Measured at baseline, week 3, and week 6.

3/13🧵

● YIAS: Internet gaming severity

● ARS: Attention deficits

● BIS/BAS: Impulsivity

● BDI: Depressive symptoms

● CGI-S: Global clinical severity

Measured at baseline, week 3, and week 6.

3/13🧵

Bupropion led to greater improvement in global function and addiction severity.

Participants receiving bupropion had significantly greater reductions in CGI-S and YIAS scores compared to both escitalopram and observation.

4/13🧵

Participants receiving bupropion had significantly greater reductions in CGI-S and YIAS scores compared to both escitalopram and observation.

4/13🧵

Only bupropion improved attentional control and impulsivity.

ARS scores: ↓ inattention

BIS scores: ↓ impulsivity

Escitalopram showed no effect on these dimensions.

5/13🧵

ARS scores: ↓ inattention

BIS scores: ↓ impulsivity

Escitalopram showed no effect on these dimensions.

5/13🧵

Mood symptoms were not different between groups.

No statistically significant difference in BDI score reduction was observed between groups (p = 0.81).

6/13🧵

No statistically significant difference in BDI score reduction was observed between groups (p = 0.81).

6/13🧵

What explained the overall clinical improvement? Not depression.

Regression analysis showed that reductions in CGI-S scores were significantly associated with improvements in:

● Internet gaming severity (YIAS)

● Attention deficits (ARS)

● Impulsivity (BIS)

Changes in depressive symptoms (BDI) did not significantly predict global clinical response.

7/13🧵

Regression analysis showed that reductions in CGI-S scores were significantly associated with improvements in:

● Internet gaming severity (YIAS)

● Attention deficits (ARS)

● Impulsivity (BIS)

Changes in depressive symptoms (BDI) did not significantly predict global clinical response.

7/13🧵

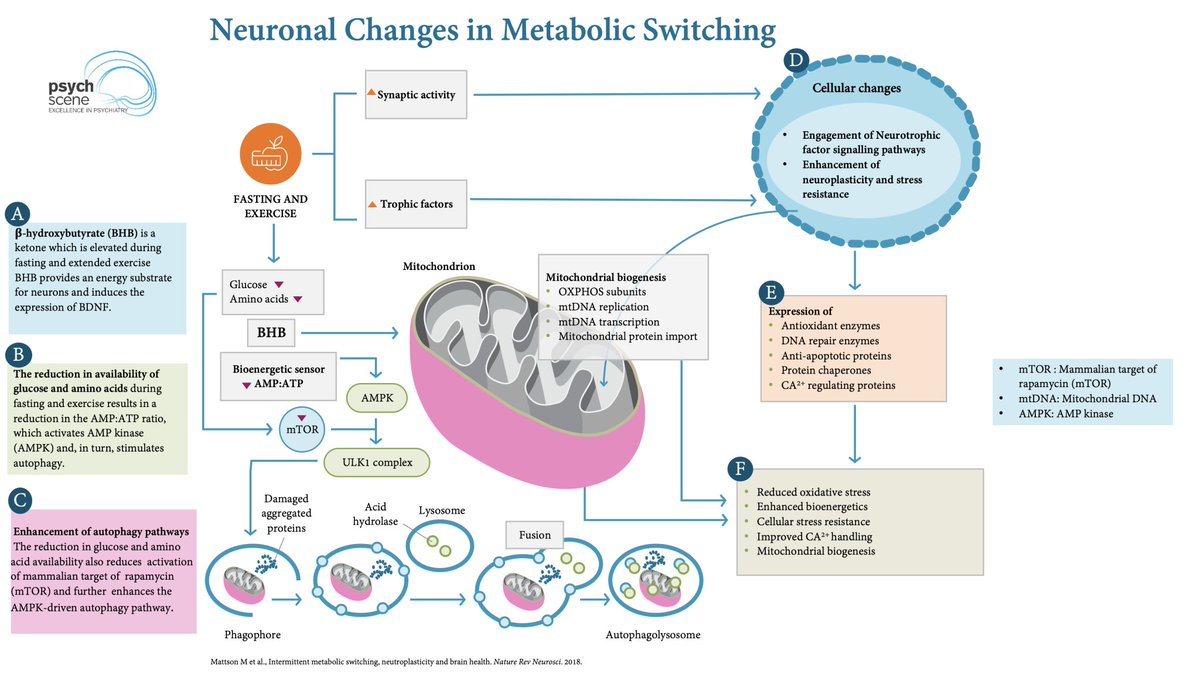

Mechanistically, bupropion may better match IGD pathophysiology.

Its dual action on dopamine and norepinephrine targets the disrupted reward and executive control circuits implicated in IGD.

8/13🧵

Its dual action on dopamine and norepinephrine targets the disrupted reward and executive control circuits implicated in IGD.

8/13🧵

Escitalopram fell short, especially for cognitive control.

The SSRI’s serotonergic profile showed no benefit for attention or impulsivity in this cohort.

9/13🧵

The SSRI’s serotonergic profile showed no benefit for attention or impulsivity in this cohort.

9/13🧵

Important limitations to consider:

● Male-only sample

● Short study duration (6 weeks)

● No placebo group

● Cultural setting (South Korea) may limit broader applicability

10/13🧵

● Male-only sample

● Short study duration (6 weeks)

● No placebo group

● Cultural setting (South Korea) may limit broader applicability

10/13🧵

Clinical interpretation:

In young adult males with IGD and executive dysfunction, bupropion may offer greater benefit than escitalopram, particularly for attentional and behavioural regulation.

11/13🧵

In young adult males with IGD and executive dysfunction, bupropion may offer greater benefit than escitalopram, particularly for attentional and behavioural regulation.

11/13🧵

Future research directions:

● Inclusion of female participants

● Longer-term outcome tracking

● Combination therapy with CBT

● Cognitive and functional outcomes

12/13🧵

● Inclusion of female participants

● Longer-term outcome tracking

● Combination therapy with CBT

● Cognitive and functional outcomes

12/13🧵

Want to improve your ability to identify, assess, and manage Internet Gaming Disorder?

Take our “Breaking the Spell of Internet Gaming Addiction” course with Dr Huu Kim Le and gain evidence-based strategies for treating gaming disorder, ADHD comorbidity, and supporting families.

Enrol now and earn CPD points while building expertise:

academy.psychscene.com/courses/gaming…

13/13🧵

Take our “Breaking the Spell of Internet Gaming Addiction” course with Dr Huu Kim Le and gain evidence-based strategies for treating gaming disorder, ADHD comorbidity, and supporting families.

Enrol now and earn CPD points while building expertise:

academy.psychscene.com/courses/gaming…

13/13🧵

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh