Tesla finally opens its first India showroom in Mumbai's Bandra-Kurla Complex, taking orders for the Model Y at ₹60 lakh. But behind this entry lies a 4-year negotiation deadlock and a question: is Tesla too late to India's EV party?🧵👇

Tesla's Indian subsidiary launched in 2021, but talks stalled over a familiar dispute. Tesla wanted lower import duties. India demanded local manufacturing. This detente signals more than just Tesla's entry—it reveals India's evolving automotive ambitions.

India has always wielded some of the world's highest car import tariffs—even reaching 110%. The reason? Industrial policy. We've consistently kept foreign automakers from capturing our market before domestic players could compete, using tariffs to force local investment.

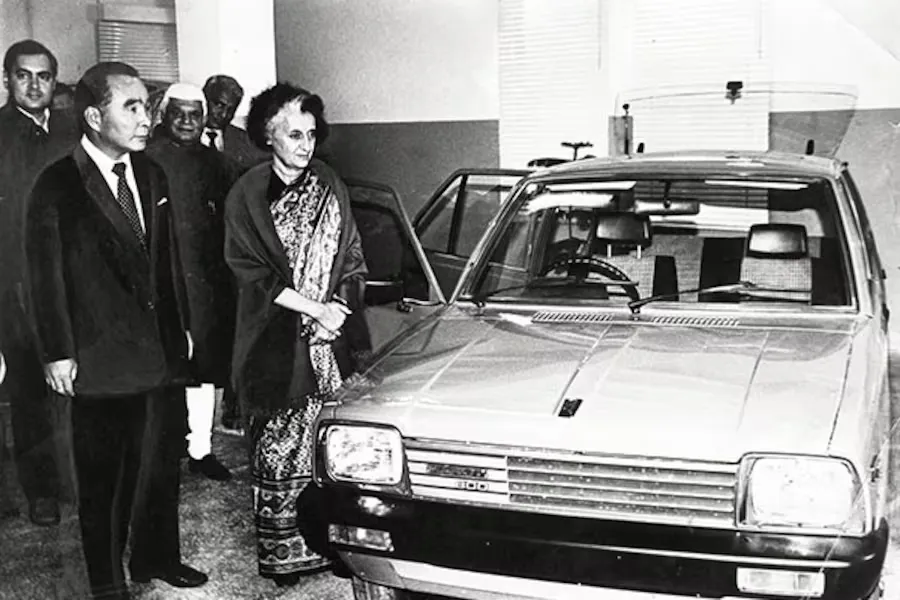

This strategy worked. Foreign carmakers like Maruti Suzuki came to India, brought expertise, and set up factories to escape duties. Post-1991 reforms made entry easier—100% foreign equity, fewer sourcing rules, tax breaks—but the message remained clear: build here to sell here.

Global automakers flocked to India, often importing parts and assembling locally. Chennai became the "Detroit of India." But despite favorable investment climate, restrictive laws caused spectacular failures, creating a graveyard of foreign car brands.

Ford's story is telling. Entered in 1995, spun off subsidiary by 1998, but assumed Indians would buy their existing models unchanged. They launched the Ford Escort—a large, expensive sedan built for right-hand driving. It flopped badly in our market.

Indian consumers in the 2000s wanted smaller cars, maximum value, strong resale potential, and vehicles suited for Indian roads. Ford eventually tried India-specific models like the Ikon, but expensive maintenance and rare spare parts couldn't compete with Maruti-Suzuki and Hyundai's wider, cheaper lineups.

Ford exited in 2021, leaving thousands jobless and dealers burned. They joined a long list of failures: General Motors, Fiat, Daewoo, Mitsubishi—all unable to crack India's tough, hyper-competitive market despite years of trying.

Tesla faces an even steeper challenge. The Model Y carries a crushing 70% import tariff, explaining its ₹60 lakh price tag. Elon Musk has publicly criticized our tariffs, but India's industrial policy remains non-negotiable.

India offers foreign EV makers just 15% import duties, but with strict conditions: invest $500M within 3 years, achieve 25% domestic value-addition by year 3 (50% by year 5), and post bank guarantees equivalent to foregone duties. These terms are stricter than anything Ford faced.

The policy has flipped from carrots to sticks. Earlier, incentives encouraged targets. Now, incentives only come after meeting targets. Union Minister HD Kumaraswamy confirmed last month: Tesla remains unwilling to set up Indian manufacturing.

Tesla's playbook mirrors Ford's mistakes: global designs without India-specific modifications, limited model portfolio, no local manufacturing base. But Tesla has one advantage Ford lacked—India's exploding millionaire population hungry for luxury.

Luxury car sales crossed 50,000 units last year, growing at 20%—double mainstream cars' pace. Mercedes-Benz India hit record sales, with average selling prices jumping from ₹57 lakh to ₹88 lakh since 2020. The luxury market has real purchasing power now.

Within luxury, EVs are surging. January-May 2025 saw 66% growth in luxury EV sales, capturing 11% of the luxury segment despite heavy import duties. Tesla plans to ride this wave, even building charging stations across tier-1 cities with 4 promised for Mumbai.

Tesla's pricing strategy avoids competition entirely. At ₹60 lakh, it's not competing with Indian EVs or even BYD (whose Sealion 7 costs ₹6 lakh less). Industry experts believe Tesla is banking on brand power and anti-China sentiment rather than features.

But globally, Tesla is struggling. Its EV market share fell from 75% in 2022 to 50% in 2024 in the US alone. This year brought its biggest sales decline ever, first back-to-back yearly drops, and profits crashed 71%. Chinese competitors are winning through aggressive pricing.

Tesla's inventory overflows with unsold cars. JPMorgan said they couldn't find a similar stock crash in automotive history. Tesla desperately needs new markets. After China, India might be its only hope—making Tesla more dependent on India than vice versa.

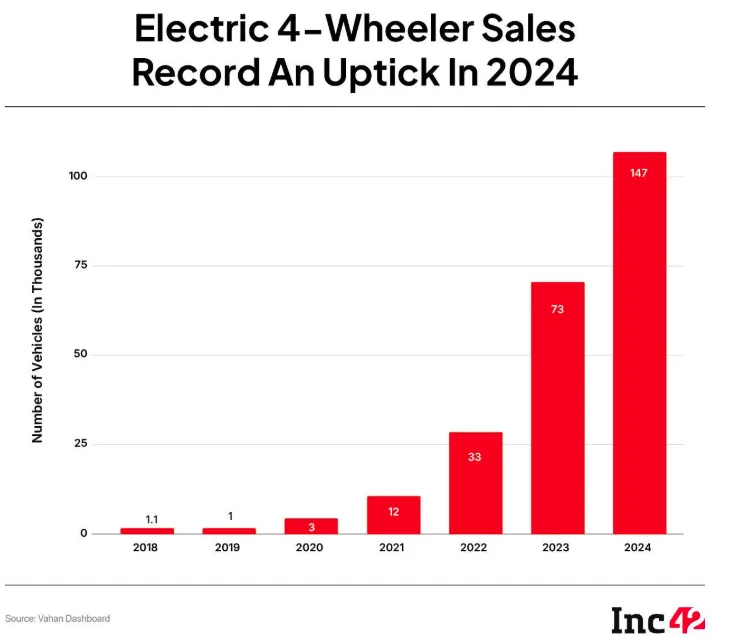

Meanwhile, India's FAME scheme doubled EV sales to 1.5 lakh four-wheelers, with Tata and Mahindra emerging as major players. Foreign companies like Skoda, Volkswagen, Hyundai, and Kia are now entering under India's evolved EV policy.

Does Tesla risk being late to India’s EV gold rush? This could well be one of the most important questions for the company’s survival.

Does Tesla risk being late to India’s EV gold rush? This could well be one of the most important questions for the company’s survival.

We cover this and one more interesting story in today's edition of The Daily Brief. Watch on YouTube, read on Substack, or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/the-off-shor…

All links here:thedailybrief.zerodha.com/p/the-off-shor…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh