Just read @vincent_rollet's incredible paper on effects of upzoning in NYC.

Wow, wow, wow!

If CA were a well-governed state, we'd be offering Meta-like pay to bring folks like Vincent into @California_HCD & @Cal_LCI.

🧵/16, with the highlights.

Wow, wow, wow!

If CA were a well-governed state, we'd be offering Meta-like pay to bring folks like Vincent into @California_HCD & @Cal_LCI.

🧵/16, with the highlights.

https://twitter.com/albrgr/status/1947737742777192557

Vincent develops a parcel-level, gen-equilibrium model of development in NYC, accounting for parcel traits like size/value of existing uses, & estimating n'hood & endogenous amenities, wages, builder cost function, extensive & intensive margins of the redevelopment decision.

/2

/2

He obtains results not only the effect of upzoning on housing-supply and prices, but also on the distribution of welfare gains/losses across the socioeconomic spectrum and as between current and future residents of NYC.

/3

/3

Here are some of the really cool results:

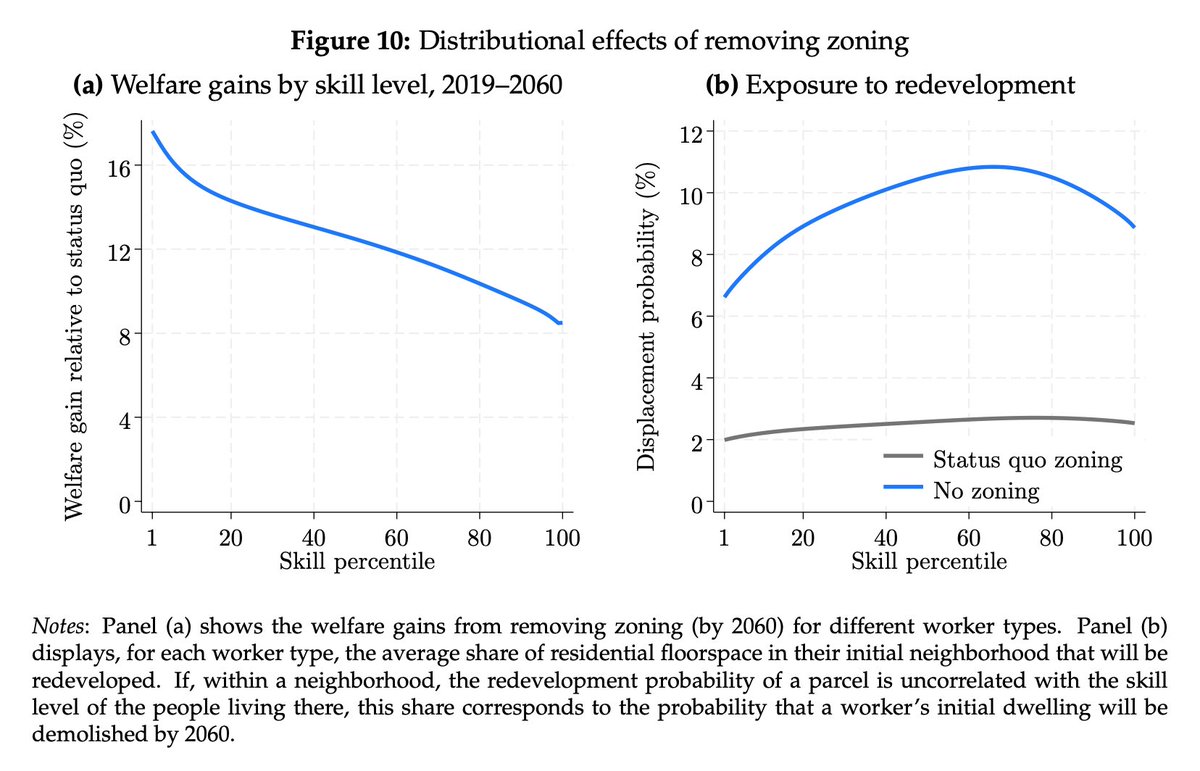

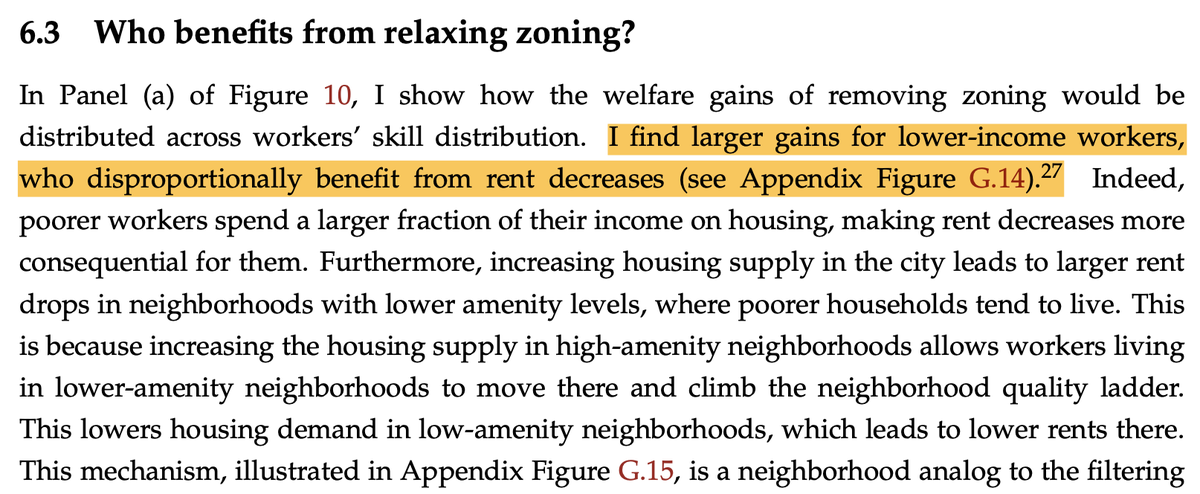

In the "no zoning" counterfactual, redevelopment would predominantly occur in high-price neighborhoods, yet the welfare gains would be disproportionately concentrated at the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum!

/4

In the "no zoning" counterfactual, redevelopment would predominantly occur in high-price neighborhoods, yet the welfare gains would be disproportionately concentrated at the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum!

/4

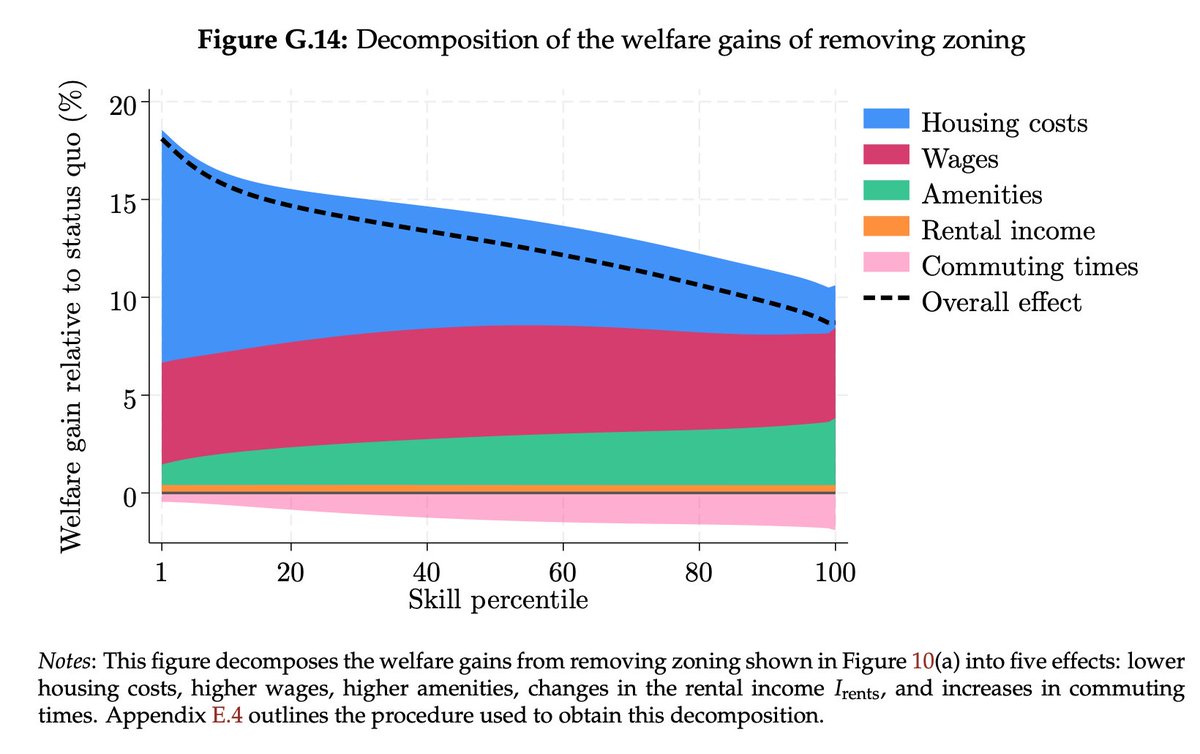

Low-income households would benefit primarily through lower housing prices, whereas households higher up the ladder would benefit more via endogenous amenities & wages.

/5

/5

Though upzoning induces more development in high-price submarkets, the effect on rents is greatest at the *bottom* end of the housing market.

(Incidentally, this destroys the theory of "impacts" that is the legal justification for inclusionary zoning.)

/6

(Incidentally, this destroys the theory of "impacts" that is the legal justification for inclusionary zoning.)

/6

Translated into lay parlance:

"Building loads of new luxury housing would be pretty sweet for the rich people who get to live in it, and FRIGGIN' AWESOME for the poor people who have to live elsewhere."

Not intuitive. But so important for policymakers to understand.

/7

"Building loads of new luxury housing would be pretty sweet for the rich people who get to live in it, and FRIGGIN' AWESOME for the poor people who have to live elsewhere."

Not intuitive. But so important for policymakers to understand.

/7

The fitted general-equilibrium model allows many valuable policy simulations, such as comparing the effect of upzoning w/ effects of reducing development costs or offering tax breaks for new housing.

Upzoning crushes the alternatives in NYC.

/8

Upzoning crushes the alternatives in NYC.

/8

But that's partly b/c NYC has really high housing prices (in high-demand n'hoods) relative to construction costs.

If NYC had Miami or Chicago housing prices w/ NYC construction costs, upzoning would yield much, much less housing.

/9

If NYC had Miami or Chicago housing prices w/ NYC construction costs, upzoning would yield much, much less housing.

/9

What about IZ? The paper estimates that a 20% IZ mandate would modestly reduce housing development under status-quo zoning, w/ larger adverse effects if zoning were liberalized.

(Remember, it's the poor who suffer most from that forgone luxury housing...)

/10

(Remember, it's the poor who suffer most from that forgone luxury housing...)

/10

There are many, many other interesting results. E.g.,:

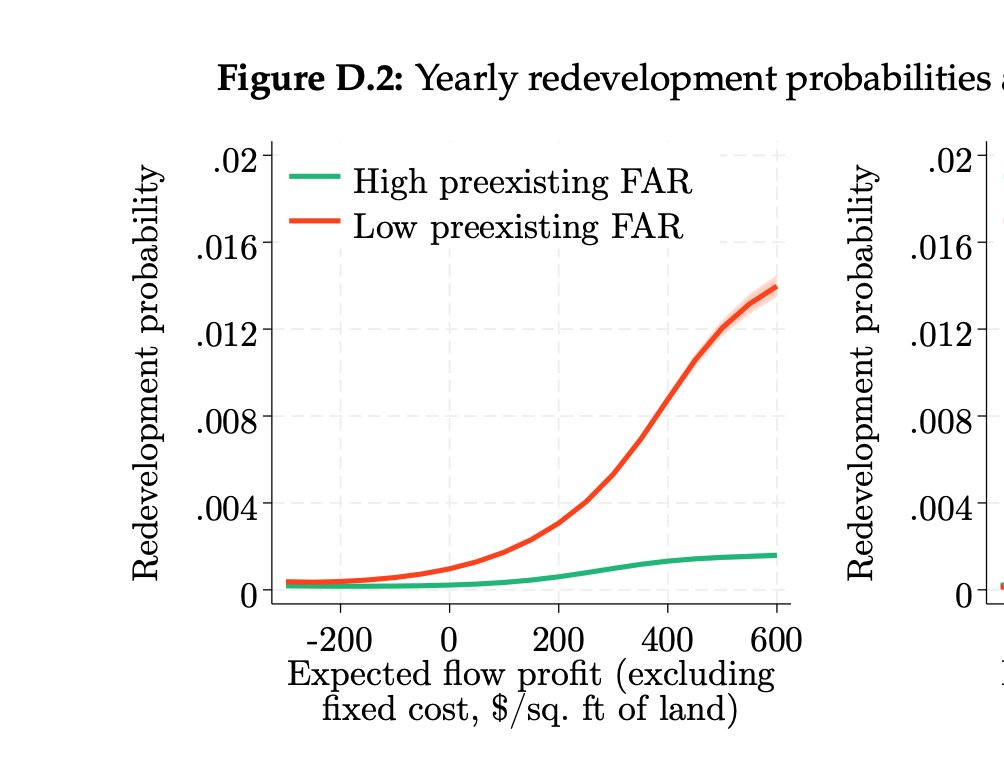

- The existing built env't creates huge path dependencies. Redevelopment is extremely rare except on sites where zoning allows the existing structure to replaced w/something much bigger. (@sfplanning, please read!)

/11

- The existing built env't creates huge path dependencies. Redevelopment is extremely rare except on sites where zoning allows the existing structure to replaced w/something much bigger. (@sfplanning, please read!)

/11

- Redevelopment probabilities on good sites increase ~linearly with "flow profit," above threshold ~$200/sqft.

Translation: in real world, where sites have existing uses, policymakers can't charge "value capture" levies (IZ, impact fees, etc.) w/o stanching development.

/12

Translation: in real world, where sites have existing uses, policymakers can't charge "value capture" levies (IZ, impact fees, etc.) w/o stanching development.

/12

- Sites that were upzoned over the study period (2002 - 2019) were *highly* selected on development potential.

Lesson for policymakers: probabilities of development naively estimated from previously upzoned sites almost certainly overstate true p(dev) for other sites.

/13

Lesson for policymakers: probabilities of development naively estimated from previously upzoned sites almost certainly overstate true p(dev) for other sites.

/13

- Big developments have ~0 "external costs," on net. Congestion costs are offset by agglomeration (wage) benefits. The paper also confirms earlier work finding that new development tends to modestly depress rather than raise rents in nearby buildings.

/14

/14

Let's take a step back. CA has spent ~$25b on housing programs since 2019.

Yet there isn't a single staff economist at @California_HCD, or serving the Senate and Assembly housing committees.

/15

Yet there isn't a single staff economist at @California_HCD, or serving the Senate and Assembly housing committees.

/15

https://x.com/CSElmendorf/status/1914525071265423627

Grad students like @vincent_rollet are unlocking deep mysteries of urban economics & estimating parameters that are absolutely central to state housing policy (e.g., sites p(dev) under alternative regulations).

Will anyone in state gov't hear what they say?

/end

Will anyone in state gov't hear what they say?

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh