The fate of the Peloponnesian War was not decided by battles.

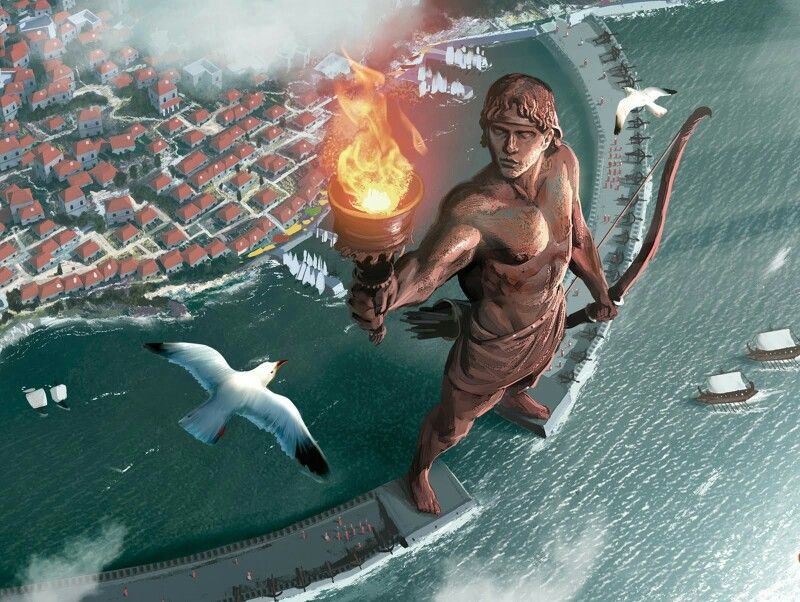

Athens was unstoppable: economic and military might, naval supremacy and cultural wealth were some of its strengths fueling imperial dreams.

They would conquer the world; but they got hit by an African plague..🧵⤵️

Athens was unstoppable: economic and military might, naval supremacy and cultural wealth were some of its strengths fueling imperial dreams.

They would conquer the world; but they got hit by an African plague..🧵⤵️

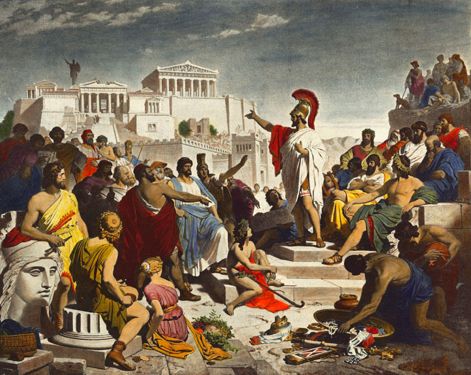

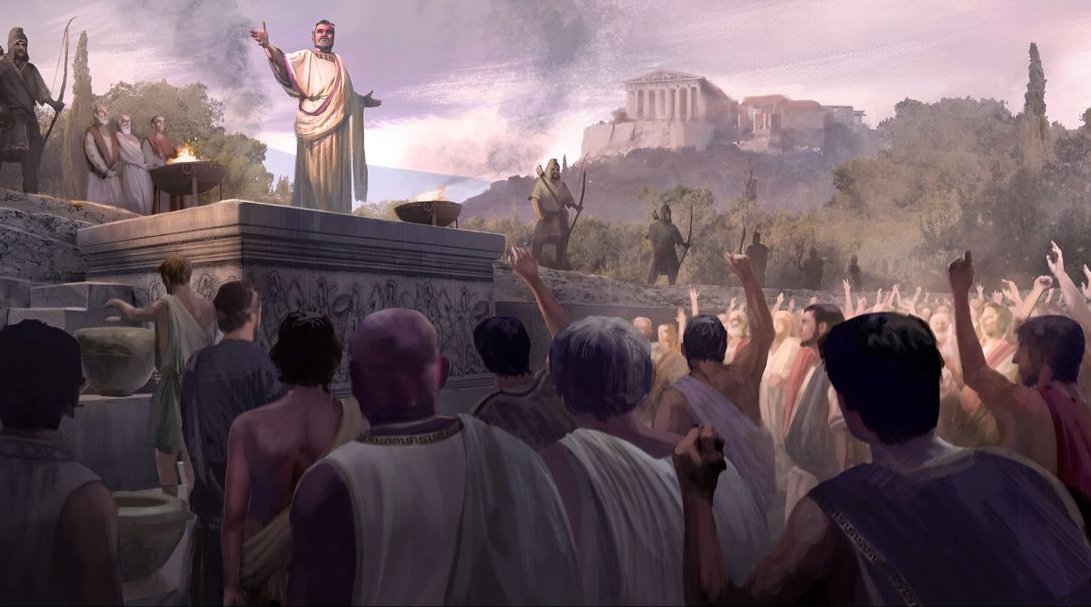

The plague hit Athens in 430 BC, during the second year of the war between Athens and Sparta. Athens, under Pericles’ leadership, adopted a defensive strategy, withdrawing its population behind the city’s Long Walls, leading to overcrowding and poor sanitation.

As the Peloponnesian War began, Athens adopted a defensive strategy under its revered leader, Pericles. Retreating behind the city’s Long Walls, Athenians abandoned their rural lands to Spartan raids, relying on their navy and fortified port to outlast their enemy.

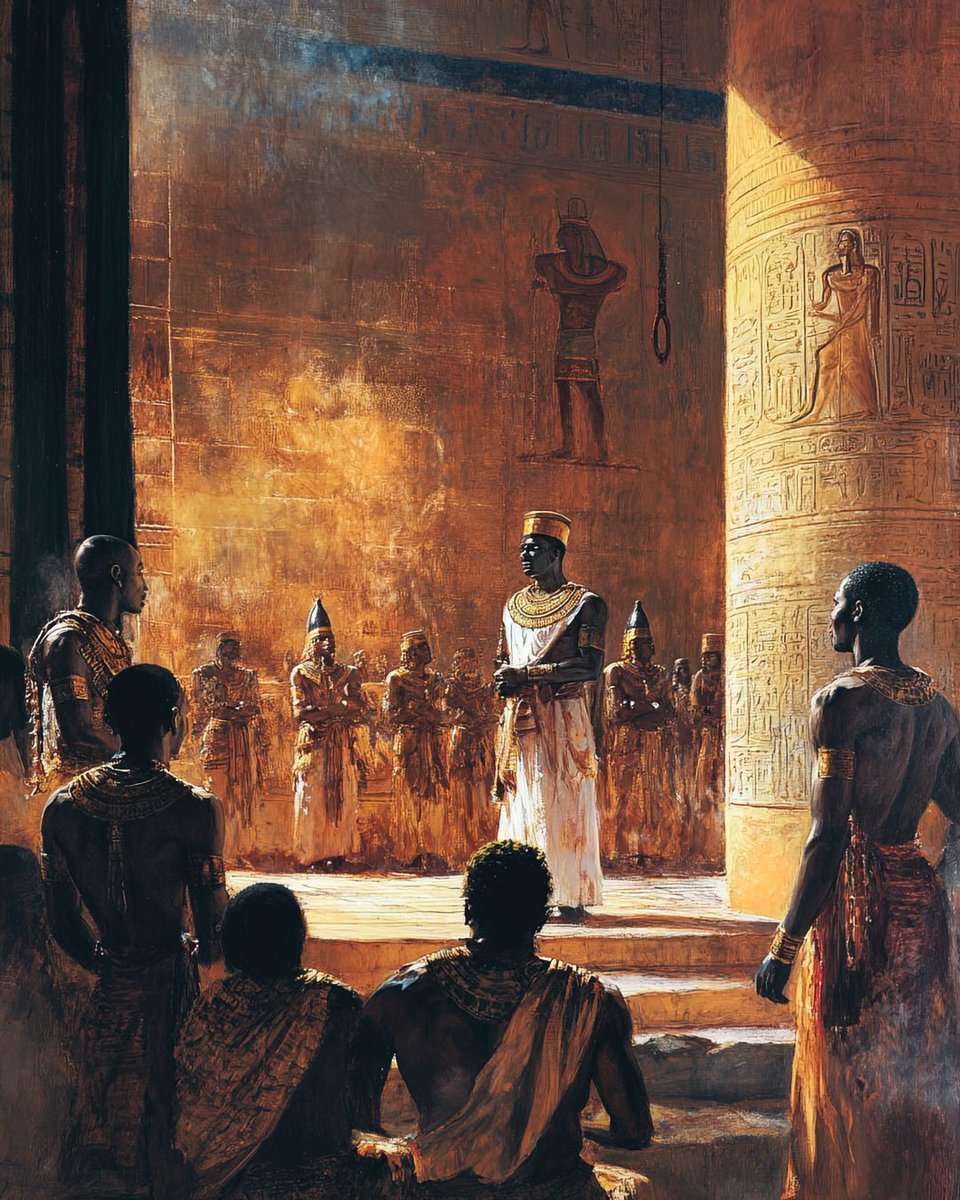

He says that the epidemic started from the lands below the Nile, in what the Greeks called Ethiopia (deep Africa); he says that it spread in Egypt and Cyrene (Libya) before hitting the Persian Empire.

Into this chaos came the plague, likely introduced through Athens’ bustling port of Piraeus. Thucydides, a survivor (and our primary source), described its horrors:

“People in good health were all of a sudden attacked by violent heats in the head, and redness and inflammation in the eyes, the inward parts, such as the throat or tongue, becoming bloody and emitting an unnatural and fetid breath.”

“People in good health were all of a sudden attacked by violent heats in the head, and redness and inflammation in the eyes, the inward parts, such as the throat or tongue, becoming bloody and emitting an unnatural and fetid breath.”

Victims suffered fever, vomiting, and pustules, with many dying within days. Estimates suggest one-third to two-thirds of Athens’ population perished, including up to 4,400 hoplites and 300 cavalry in the first wave alone.

The plague struck at Athens’ military core, crippling its ability to wage war. The city’s strength lay in its navy, which dominated the Aegean and secured the tribute funding its empire. But the epidemic decimated sailors and soldiers, leaving ships undercrewed and garrisons depleted.

Campaigns like the siege of Potidaea dragged on, strained by troop shortages. Thucydides notes that the plague “cut off the flower of their youth,” weakening Athens’ capacity for offensive operations.

Campaigns like the siege of Potidaea dragged on, strained by troop shortages. Thucydides notes that the plague “cut off the flower of their youth,” weakening Athens’ capacity for offensive operations.

Meanwhile, Sparta, with its dispersed rural population, largely escaped the disease. Though fear of infection kept Spartan armies from exploiting Athens’ vulnerability directly, their relentless raids on Attica compounded the city’s woes, as survivors faced starvation and displacement.

The plague forced Athens to lean heavily on allies and mercenaries, straining its finances and alliances.

The plague forced Athens to lean heavily on allies and mercenaries, straining its finances and alliances.

The plague’s most enduring impact was the death of Pericles in 429 BC, a loss that destabilized Athens’ leadership. Pericles had championed a cautious strategy, avoiding risky land battles and leveraging Athens’ naval supremacy.

His death, as Thucydides laments, left the city in the hands of “less capable” leaders like Cleon and Alcibiades, whose ambition often outstripped prudence.

His death, as Thucydides laments, left the city in the hands of “less capable” leaders like Cleon and Alcibiades, whose ambition often outstripped prudence.

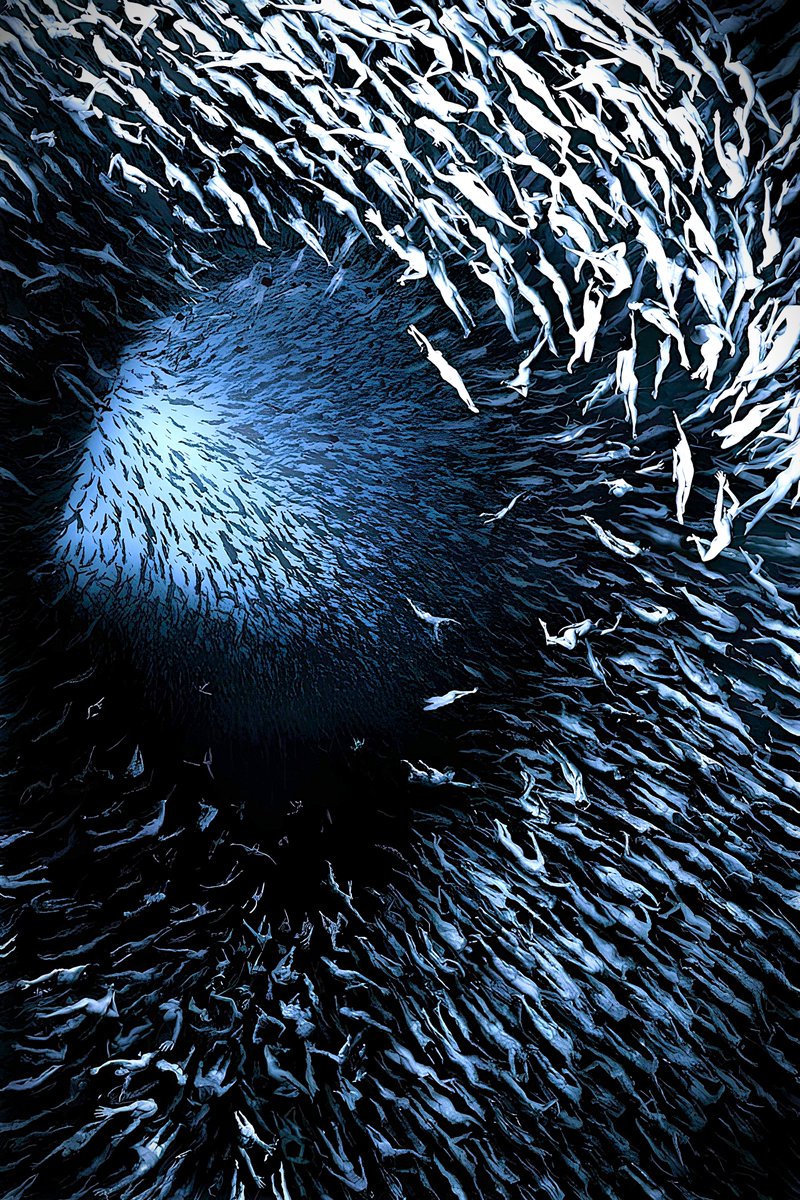

Beyond the battlefield, the plague unraveled Athens’ social fabric. Thucydides paints a grim picture of a city where “men now did just what they pleased.”

With death seemingly inevitable, citizens abandoned burial rites, neglected laws, and indulged in hedonism. Temples overflowed with corpses, and families left loved ones unburied.

With death seemingly inevitable, citizens abandoned burial rites, neglected laws, and indulged in hedonism. Temples overflowed with corpses, and families left loved ones unburied.

This breakdown eroded the civic unity essential for wartime resilience. The psychological toll was profound: survivors, witnessing divine indifference and societal collapse, lost faith in Athens’ imperial destiny. This despair weakened public support for the war, as citizens questioned the cost of their city’s ambitions.

Economically, the plague strained Athens’ maritime empire. The loss of manpower disrupted trade and tribute collection, while the costs of maintaining defenses and funding campaigns drained the treasury. Agricultural production in Attica plummeted as rural refugees remained trapped in the city.

Athens could have built a first Hellenic Empire, before Macedonians. The Plague stands as a stark reminder that even the greatest powers can be humbled by forces beyond their control.

Its devastation not only claimed countless lives but also fractured Athens’ military might, political stability, and societal cohesion, tilting the Peloponnesian War’s balance toward Sparta.

Its devastation not only claimed countless lives but also fractured Athens’ military might, political stability, and societal cohesion, tilting the Peloponnesian War’s balance toward Sparta.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh