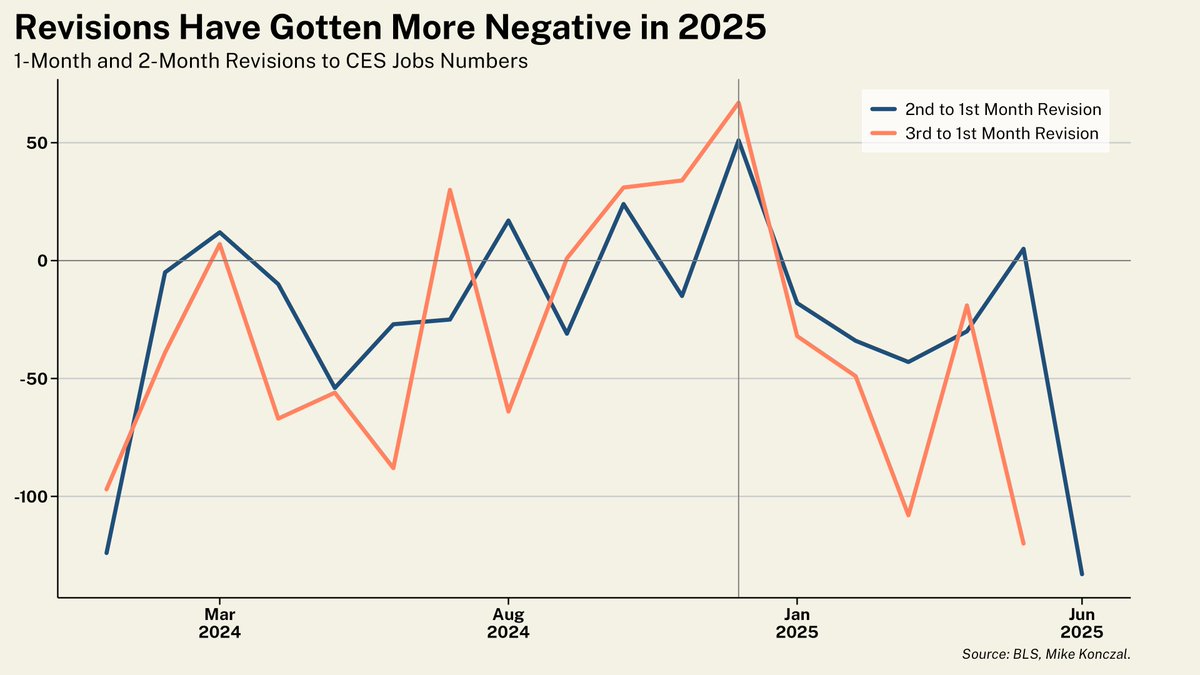

Job revisions have a well-known strong cyclical component; as the economy slows it is more difficult to estimate business births and deaths.

Here's average revisions as % employment for 18 months before and after a recession, from 1979 to 2025. It's negative in the slowdown. /1

Here's average revisions as % employment for 18 months before and after a recession, from 1979 to 2025. It's negative in the slowdown. /1

Or consider the last decade. Essentially zero pre-covid.

Sharply negative under lockdowns. But very positive when the economy was gaining millions of jobs back in 2021, as the models couldn't keep up with recovery. But then negative as that recovery leveled out in 2023-2024. /2

Sharply negative under lockdowns. But very positive when the economy was gaining millions of jobs back in 2021, as the models couldn't keep up with recovery. But then negative as that recovery leveled out in 2023-2024. /2

Here you can see that with a longer-timeframe. This is very common.

The question right now, as it was in 2023, is whether the revisions indicate slowing into a lower stable steady-state (as it did then), or an actual downward freefall. 3/4

The question right now, as it was in 2023, is whether the revisions indicate slowing into a lower stable steady-state (as it did then), or an actual downward freefall. 3/4

Trump firing Erika Mcentarfer is despicable by itself and threaten our general prosperity.

But make no mistake: there is nothing abnormal about revisions at this point in a business cycle. This administration is slowing the economy in the short-term and revisions result. 4/4

But make no mistake: there is nothing abnormal about revisions at this point in a business cycle. This administration is slowing the economy in the short-term and revisions result. 4/4

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh